On the Front Lines

Elevating the Voices of Violence Intervention Workers

In December 2022, “On The Front Lines” received the Equity and Justice Award at the National Research Conference on Firearm Injury Prevention. We want to extend our deepest thanks to our partners for offering their guidance throughout this project and hope that this recognition manifests into tangible change for our homegrown peacemakers

Introduction

I’d been a community violence intervention worker in Compton, California, for two weeks. We were in our company van, driving around at night like we often did, looking for people at risk of causing violence—usually gang members we talked to regularly to prevent the next shooting.

My boss, who’s driving, says, “There’s Trayvon,” as he slows down and pulls up to a tall Black man in his early twenties walking alone. Trayvon recognizes the van and makes his way to the sidewalk to meet us. My boss and coworker in the passenger seat know Trayvon well, and they begin to catch up. This goes on for quite some time.

On the Front Lines: Executive Summary

I remember sitting there thinking, “We’re wasting time—we could be stopping a potential gang war somewhere else, but instead we are babysitting this guy!” As community violence intervention (CVI) workers,1 our job was to do anything morally, ethically, and legally possible to interrupt violence and broker peace agreements between rivaling individuals and groups.

Trayvon goes on a long rant about his problems and how he regrets dropping out of our career development program and wants to come back. My boss says, “You know you’re always welcome, but you got to meet us halfway. Come to the office tomorrow morning.”

As my boss starts to say goodbye, Trayvon pulls a .9 millimeter out of his pants and says, “Damn, I’m glad you came by because I was on my way to go shoot this fool that disrespected me. God must have sent you guys. I’m just gonna go home and go to sleep.”

I learned a valuable lesson that day. I learned that community violence intervention can be done in different ways and that the smallest effort can have a profound impact.

As CVI workers, we put our lives on the line to save other people. We understand that people from disenfranchised communities of color are carrying multiple layers of trauma and for various reasons, can reach a point where violence seems like the only way to resolve conflict.

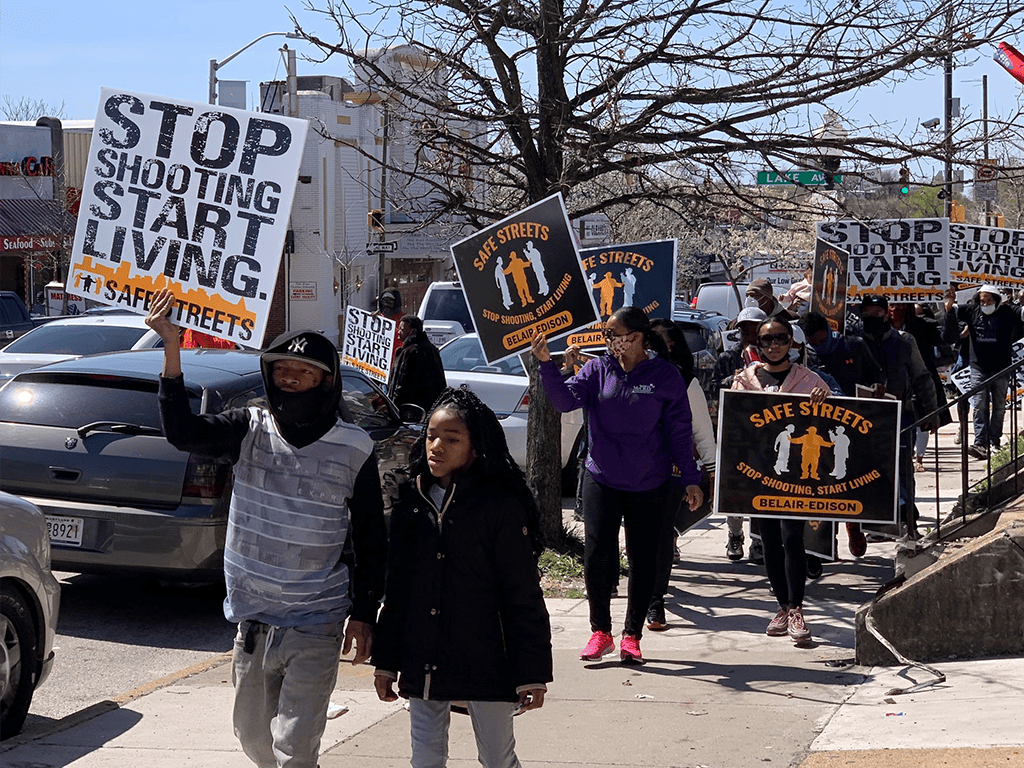

Photo courtesy of Baltimore Safe Streets

These days I’m the director of the Community Violence Initiative at Giffords, where we advocate for federal, state, local, and philanthropic funding for lifesaving interventions, including, among others:

- Street outreach

- Gang intervention

- Violence interruption

- Hospital-based violence intervention

- Case management

- Mentoring

- Life coaching

Over the past year and a half, gun violence has skyrocketed across the US, with more gun homicides in 2020 than in any other single year since 1994.2 Gun homicides rose by 33% from 2019 to 2020—the largest single-year increase since the FBI began tracking this data in the 1960s.3

Data from individual cities shows that these increases were nearly universal: cities of every size, type, and in every geographic region of the country saw large, sustained increases in homicides last year. Of the 50 largest US cities, only five saw a decrease in the number of homicides in 2020 compared to 2019.4 Nearly a fifth of these large cities saw increases in homicides greater than 60%.5

Nonfatal shootings are also on the rise: in eight of the 50 largest cities that provide up-to-date nonfatal shooting data, the number of shooting victims was up roughly 60% in 2020 compared to 2019, leading to nearly 4,000 additional shooting victims in these eight cities alone last year.6

Even more alarmingly, these trends have continued in 2021. While homicide rates have declined from their peak in the summer of 2020, year-to-date counts of homicides in 2021 are higher than they were in the same period in 2020.7

In June and July of 2021, I traveled to Chicago, Los Angeles, Baltimore, and Oakland to administer a survey to more than 200 community violence intervention workers, asking them about their compensation and benefits, training, resource needs, and the mental health impacts of their roles. It’s worth emphasizing that the workers we surveyed represent among the most well-funded and well-trained CVI workers in the country, and thus their experiences may not be shared by individuals working at smaller organizations with less stable resources. And yet, our survey still revealed tremendous gaps and shortcomings that must be addressed.

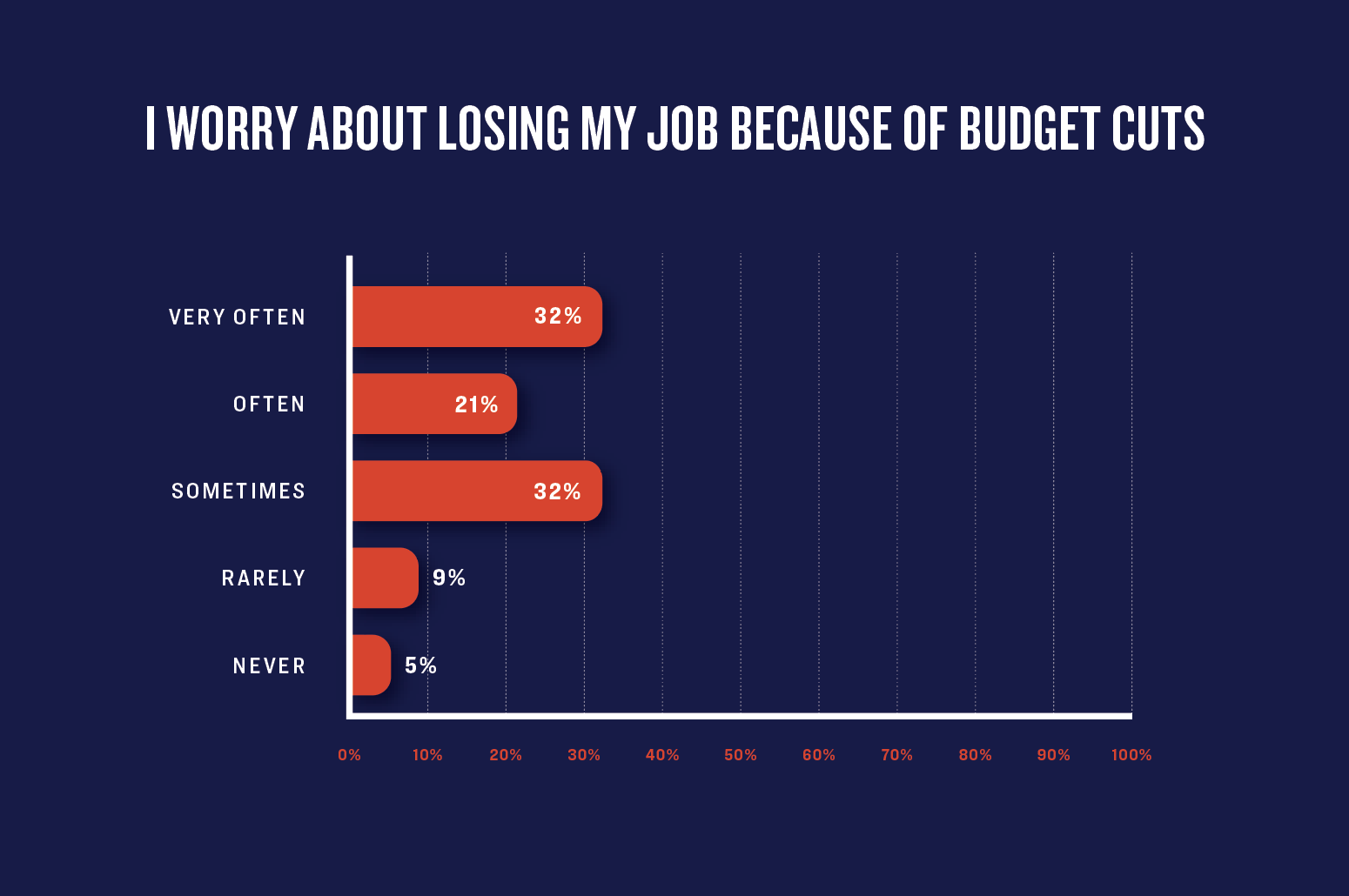

The results of our survey, explored in greater depth later in the report, highlight just how difficult and consuming this work is—and how badly existing organizations need dedicated, consistent funding to do their jobs effectively. Eighty-six percent of workers surveyed said they have occasional or frequent worries about losing their jobs due to lack of funding, while 82% of workers indicated that they worry at least occasionally about making their mortgage or rent payments.

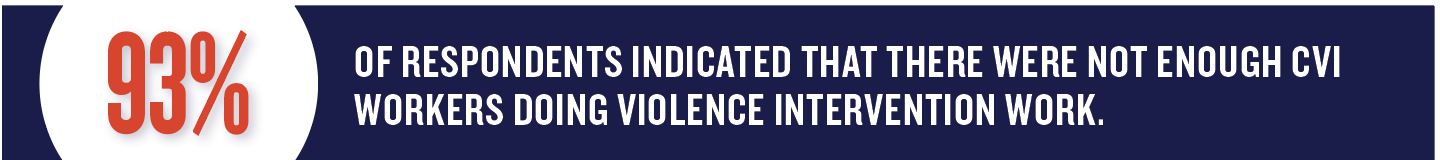

While the majority of workers surveyed reported having access to the physical resources they needed for their roles, the vast majority (93%) of respondents indicated that there were not enough CVI workers doing violence intervention and prevention work. And while 99% of respondents agreed that being able to help people at work gave them satisfaction, 53% reported that the trauma of the people they helped had some effect on them.

We used the findings from our survey and the focus group we conducted, as well as additional input from our partners, to formulate the below recommendations for CVI organizations across the country.

As is clear from the story of Trayvon above, this is dangerous work. While I was administering surveys at one Safe Streets site in Baltimore, the supervisor got a call. When he hung up, he informed us that one of his workers had just been shot. Before we finished with the surveys, he got another call saying that the worker—Kenyell “Benny” Wilson—had passed. The supervisor was stunned and visibly disturbed as we parted ways. He asked us to please use this tragic incident in the report to articulate the dangers of doing community violence intervention work.

In addition to being incredibly dangerous work, this is also extremely vital work. Cities don’t typically need to pass laws to put these programs in place, but we can and should enact state and federal laws ensuring sustainable and long-term funding. And that’s where we have a groundbreaking opportunity at our fingertips.

America at a Crossroads: Reimagining Federal Funding to End Community Violence

Brittany Nieto, Mike McLively—Dec 17, 2020

The Biden administration has proposed $5 billion in federal funding for community violence intervention programs in impacted neighborhoods. As Giffords explored in a report last winter, federal funding aimed at reducing gun violence has often done more harm than good, fueling mass incarceration while failing to have any meaningful effect on reducing gun violence.

It’s time for a new approach. And given the tragic increases in gun violence that cities across the country have seen over the past year and a half, there’s no time to waste.

We’re especially grateful to our partners in this report: Chicago CRED, the Mayor’s Office of Neighborhood Safety and Engagement in Baltimore, the City of Oakland Department of Violence Prevention, and the Urban Peace Institute in Los Angeles for their collaboration, invaluable insight, and dedication to elevating the voices of CVI workers. We’re more grateful still for the lifesaving work these organizations do each and every day.

We offer our gratitude for every bullet not fired because of the heroic efforts of CVI workers, and pledge to keep fighting to get them the resources and support they need to do their jobs as safely and effectively as possible.

With gratitude,

Paul Carrillo

Community Violence Initiative Director

Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence

What Is Violence Intervention?

To fully understand what community violence intervention is, we must explore a definition of CVI that captures who practitioners are and how the work is done.

Community violence intervention relies on concerned individuals, native to the community, who are willing to accept the role of peacemaker and work tirelessly to reduce violence by engaging those at highest risk of being injured and/or producing violence. In communities of color, most lethal injuries are caused by gun violence, and the majority of shootings are attributed to violent groups.

For as long as there has been community violence, there have been homegrown peacemakers. Concerned parents, faith-based leaders, civil rights activists, ex-offenders, and survivors of violence have risked their lives to save others.

Community violence intervention takes place across our nation under the labels of street outreach, gang intervention, violence interruption, and others. A small handful of cities like Los Angeles and Chicago have advanced teams, training, and professional standards; however, the field remains largely under-developed due to a lack of funding and other resources from federal, state, and local governments.

The research that has emerged about these programs is extremely promising: in 2017, a joint UCLA-USC study found that over a two-year period, CVI workers in South Los Angeles reduced retaliatory gang violence by more than 43%. When only police responded to a gang-related homicide, there was a 24% chance of a retaliatory killing. But when both police and CVI workers responded separately, the likelihood of a retaliatory homicide was less than 1%.

Giffords and our partners believe that broadening the public safety narrative, long focused on law enforcement and punitive approaches like incarceration, to include community-based leaders is the future of community-level safety.

The Workers

The effectiveness of a violence intervention strategy is largely dependent on the individuals serving as violence intervention workers. A violence intervention worker is not responsible for the enforcement of laws. Rather, CVI workers utilize their credibility to develop relationships with community members and groups that might cause violence with the goal of preventing the spread of violence and building peace in a community.

It is critically important to identify individuals who meet specific criteria and qualifications and equip them with the skills they need to do the job well—while also providing fair compensation and benefits commensurate with the work. The following responsibilities, characteristics, and qualifications make up the profile of a violence intervention worker:

Responsibilities

- Build positive relationships with a wide swath of community members

- Connect community members to vital resources

- Conduct individual and group sessions

- Identify and engage influencers of violence

- Leverage existing relationships to prevent violence

- Respond to shootings and support victims’ loved ones

- Work with partners to prevent retaliatory shootings

- Facilitate mediations between rivals when possible

- Control rumors so that false narratives do not cause more violence

- Mentor individuals seeking a better life

- Work with community influencers to build long-term peace

- Advocate for nonviolence and model peace

- Adhere to professional standards and practices

Characteristics

- Commitment to working towards peace in the community

- Willingness to work with rival groups

- Ability to intervene in existing conflict

- Background working at the community level

- Experience working with individuals at highest risk for violence

- In-depth knowledge of community dynamics and culture of violence

- Awareness of existing risk and protective factors

- Credibility to engage violence producers

- Mobility across boundaries and territories

- Excellent communication skills

- In good standing with the community

- Positive and energetic work ethic

- Patience and dedication to promoting forgiveness

- Professionalism and ability not to take things personally

- Ability to collaborate and work with others

- Culturally competent

- Lack of bias, bitterness, or anger toward any group

Preferred Qualifications

- High school diploma or equivalent

- Basic computer skills

- Entry-level violence intervention training

- Ability to navigate social media

- Ability to pass drug screening

- Lack of pending criminal cases

Disqualifiers

- Criminal conviction for child abuse or sexual assault

- History of serving as an informant to, cooperating with, or working for law enforcement

The Work

There are essentially two basic approaches to community violence intervention. Both require training and a commitment to professional standards of practice. Each is incomplete without the other.

The first is the skill and ability to reach those at the highest risk, with the goal of interrupting the transmission of violence. This face-to-face interaction requires training, trust-building, and tactful methods of engaging hard-to-reach individuals. Staff with lived experience are often the most successful at engaging this group. This can be done while individuals are incarcerated, in the hospital after suffering from a violent injury, in school, or in the community. Violence intervention efforts cannot develop if those at highest risk are not properly engaged.

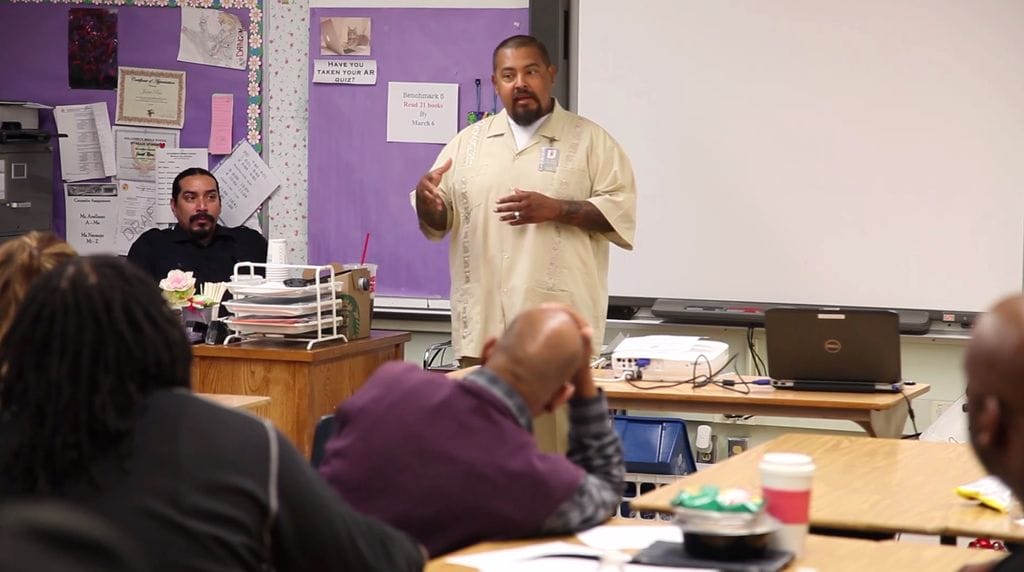

Photo courtesy of Southern California Crossroads

Second, various social services need to be provided to the individuals at highest risk who wish to change the trajectory of their lives. Trauma creates an array of complex obstacles for individuals who are at highest risk for violence. To address these obstacles, clients first receive an assessment of their challenges and needs. Based on the assessment, they are provided a tailored service plan that might include counseling, case management, tattoo removal, career development, mentoring, and child care, among others.

Survey Results

This project utilized a mixed methods approach to gather data from CVI workers in Chicago, Illinois; Los Angeles, California; Baltimore, Maryland; and Oakland, California. To ensure that our sample reflected workers whose primary role involved street outreach work, three criteria were established to determine participation in the survey. Individuals must:

- Work with those at highest risk of being shot or doing the shooting

- Spend at least 50% of work time physically in the community (outside of the office)

- Provide any of the following services to those at highest risk: case management, violence interruption, life coaching, mentoring, gang intervention, etc.

Participants were recruited through a combination of convenience sampling and snowball sampling. Eligibility criteria were communicated to site directors and supervisors in each city, who encouraged eligible staff to participate. Survey participants were also encouraged to recruit other eligible co-workers to complete the survey. Participants completed the survey on tablets through the SurveyMonkey platform. Upon completion of the survey, all participants received a $50 gift card.

Two hundred participants completed the survey. We excluded 20 responses from our sample that involved participants who were not full-time employees8 for a final analytical sample of 180 respondents. Additional details about part-time workers are included below.

During the time in which survey responses were collected, CVI workers in these four cities were grappling with surging levels of gun violence and related traumatic exposures. While these responses illustrate the trauma that outreach workers face, it is also important to remember that these experiences may have impacted both participation in and responses to our survey.

To supplement our quantitative findings, we conducted a focus group with executive directors, administrators, and other senior managers at our previously surveyed organizations. Participants selected for this group were responsible for overseeing their programs as well as having some responsibilities managing the funding coming into their organizations. The questions in these sessions were designed to help us understand administrator perspectives on how to better support workers as well as the struggles managers face in doing this work.

Demographic Characteristics of CVI Workers

The number of survey participants from each site roughly corresponded to the size of the CVI worker field in each city: 39% of respondents in our final sample worked in Chicago, 27% in Los Angeles, 19% in Oakland, and 16% in Baltimore.

The majority of CVI workers in our sample—78%—were male. The average worker was 44 years old, with workers ranging in age from 22 to 72. Workers overwhelmingly identified as people of color: 72% of workers identified as Black and 26% of workers identified as Latino. A small number of workers (5%) identified as either Native American, Asian American, and/or Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander.9

Workers in our sample had varying levels of educational experience: 21% had less than a high school diploma; 29% had a high school diploma or equivalent only; 31% had attended a trade school or some college; and 18% had obtained a college degree, including an Associate’s degree, Bachelor’s degree, Master’s degree, Doctoral degree, or other professional degree.

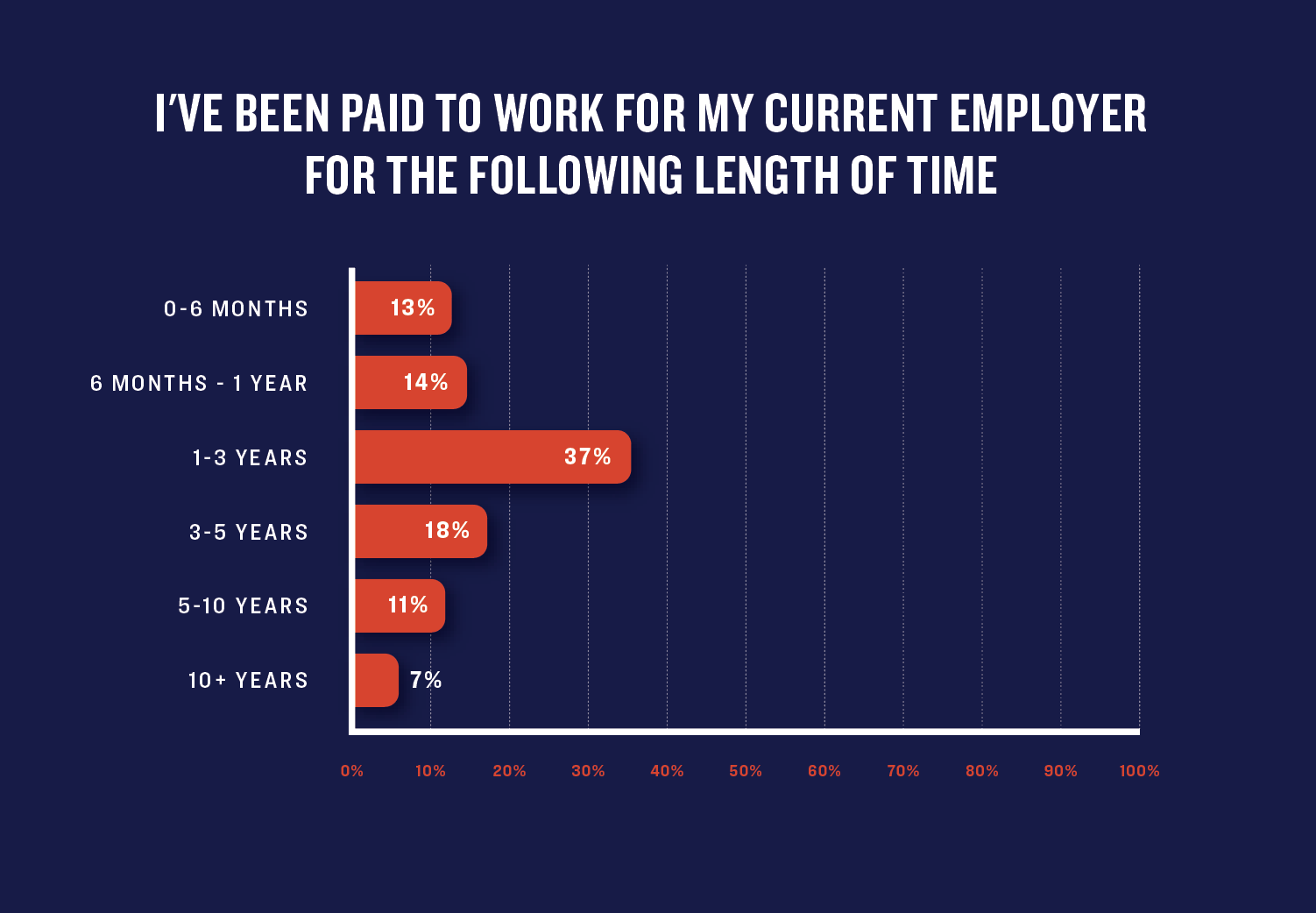

Nearly three-quarters (73%) of workers had been working for their current employer for at least one year, and approximately one in five (18%) workers had been working for their current employer for at least five years. Thirty-five percent of workers reported that they have been working in the CVI field—with any employer—for at least five years, suggesting that a number of more senior workers have likely worked for multiple employers.

Worker Compensation, Benefits, and Tangible Supports

Our survey asked a variety of questions about the kinds of tangible support that workers receive from their organizations, specifically the types of compensation, benefits, and other job-related services. Our results suggest that many CVI workers in the four cities receive some benefits and services that are comparable to those provided in other professional fields.

However, salaries among outreach workers were relatively low compared to median household income in these cities, and some results from the survey suggest that the compensation organizations are able to provide to employees is not adequate for supporting workers and their families.

Three-quarters (75%) of full-time CVI workers reported making between $30,000 and $50,000 per year. Of those within this income bracket, at least 60% reported an annual salary of less than $42,000. Fourteen percent of workers reported earning between $50,000 and $70,000 per year. Roughly the same number of workers earned less than $30,000 and more than $70,000 per year (5% and 6%, respectively).

Many workers reported receiving other benefits from their employers. Two-thirds (67%) of workers indicated that their employer provided retirement benefits, and 60% reported receiving life insurance.

Most workers also reported receiving mental health benefits and services through their employer. Seventy-eight percent of workers said that their organization provides mental health services for employees. Of those who said that mental health services were provided, 81% indicated that such services were culturally sensitive.

Ninety-five percent of workers also reported that employers at least sometimes provided dedicated debrief sessions after community crises to help address mental health concerns. Two-thirds (66%) of workers said that these debrief sessions occurred after most or all crises in their communities.

In addition to the more tangible benefits provided by organizations, many workers agreed that there were opportunities for advancement within their organization. Nearly three-quarters (74%) of workers said that their organization provided opportunities for professional development and advancement like promotions and raises. However, CVI workers who had worked with an organization longer were less likely to agree that there were opportunities for advancement available to them.10

Additionally, while the majority (72%) of workers who had been with their organization for more than one year reported that they had received a raise within the last three years, less than half (48%) reported actually receiving a raise in the last year. Nearly a quarter of workers (23%) who had been with their organization for at least three years reported that they had never gotten a raise.

Despite the benefits many workers reported receiving from their organizations, 86% of workers said they have occasional or frequent worries about losing their jobs due to a lack of funding, with nearly a third (32%) of all workers reporting that they have these concerns very often.

There is also some indication from the survey data that organizations are not able to pay workers adequate wages to meet their cost of living. Nearly 64% of workers reported that they worked one additional paid job to make ends meet, and another 12% of workers said they worked two or more additional paid jobs.

Alarmingly, many workers who work additional paid jobs also volunteer to work additional hours in their role as a CVI worker. Eighty-seven percent of full-time workers reported that they work additional hours beyond their regular work schedule at least once a month, and more than half (54%) of workers reported working these additional hours in their CVI worker role at least a few times each week.

As well as needing to supplement their income, many outreach workers also reported at least some difficulty in paying for living expenses like housing and food: 82% of workers indicated that they worry at least occasionally about making their mortgage or rent payments, with more than a quarter (27%) of workers responding that they worry about making the payments very often. While our data suggests that fewer workers experienced food insecurity, nearly 44% of workers reported skipping meals or eating less because they were concerned about affording food.

During the focus group, the administrators echoed the concerns of the CVI workers regarding low wages and inadequate benefits. Claudia Bracho, a program director working at HELPER Foundation in Los Angeles, talked about how workers at her organization were “still working under these…unhealthy conditions.” Many members of the group similarly noted that it should be a key priority for new funding to translate into improved conditions for the workers on the ground, including increased pay and mental health benefits.

Support for CVI Work

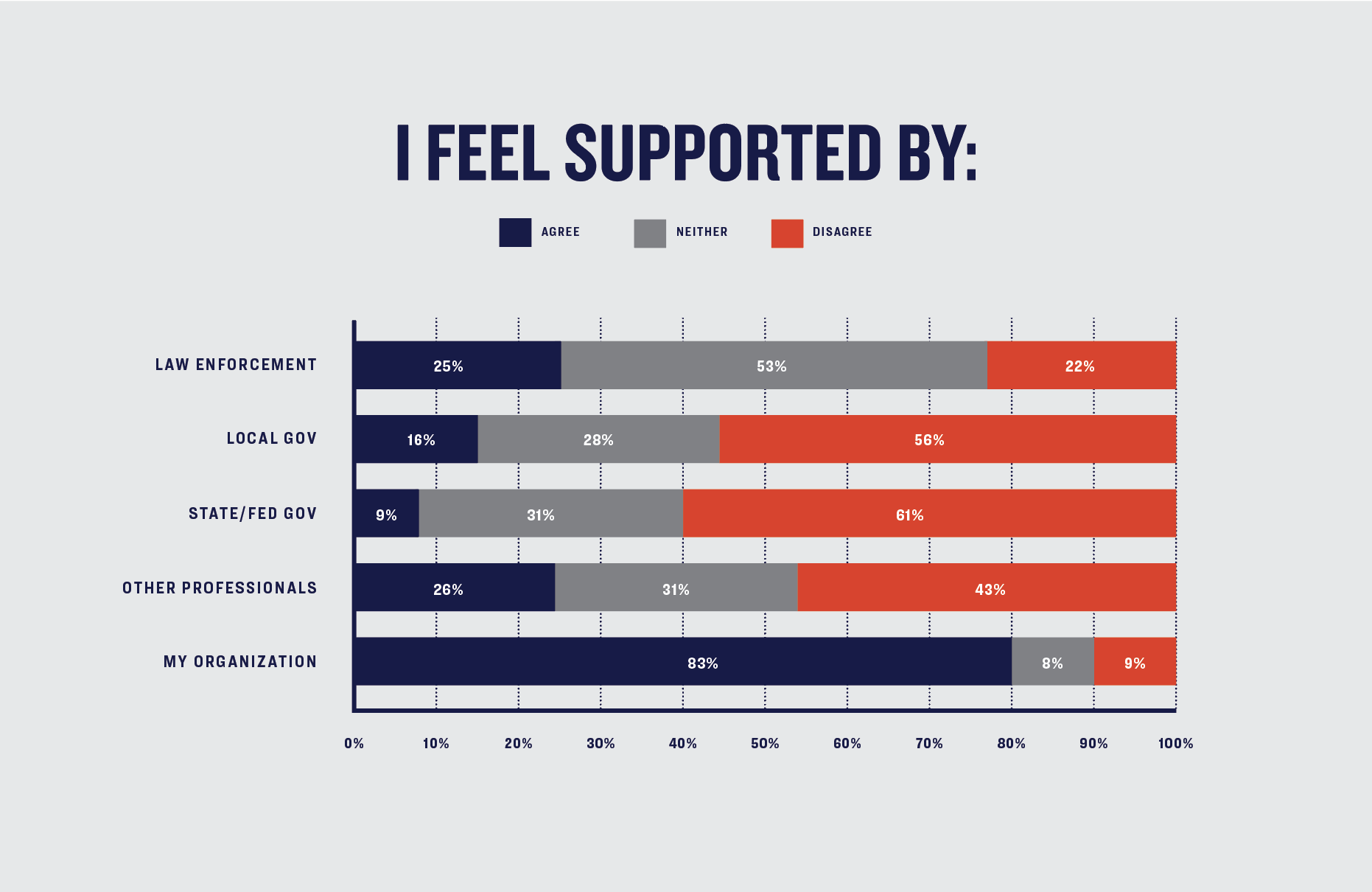

In addition to asking respondents about the support and compensation they received from their organizations, we also asked survey participants about feeling respected and valued by other professionals who work with or support CVI work.

CVI workers across the four sites overwhelmingly felt supported by their organizations, with 83% of respondents saying that in the last 30 days they always felt supported by their organization. Of those who said they felt supported, more than half (54%) said they strongly agreed with this sentiment.

Feelings of support from those outside the organization were more mixed, with respondents generally feeling more supported locally. For example, while more than half (52%) of outreach workers responded that they neither agree nor disagree that law enforcement support their work, only 22% said that they felt law enforcement did not support their work. Nevertheless, only 26% of workers fully agreed that they felt supported by law enforcement.

Compared to the number of workers who felt unsupported by law enforcement, a higher number—43%—of respondents indicated that they did not feel they were respected by other professionals they worked with in their role, such as hospital workers and emergency services workers.

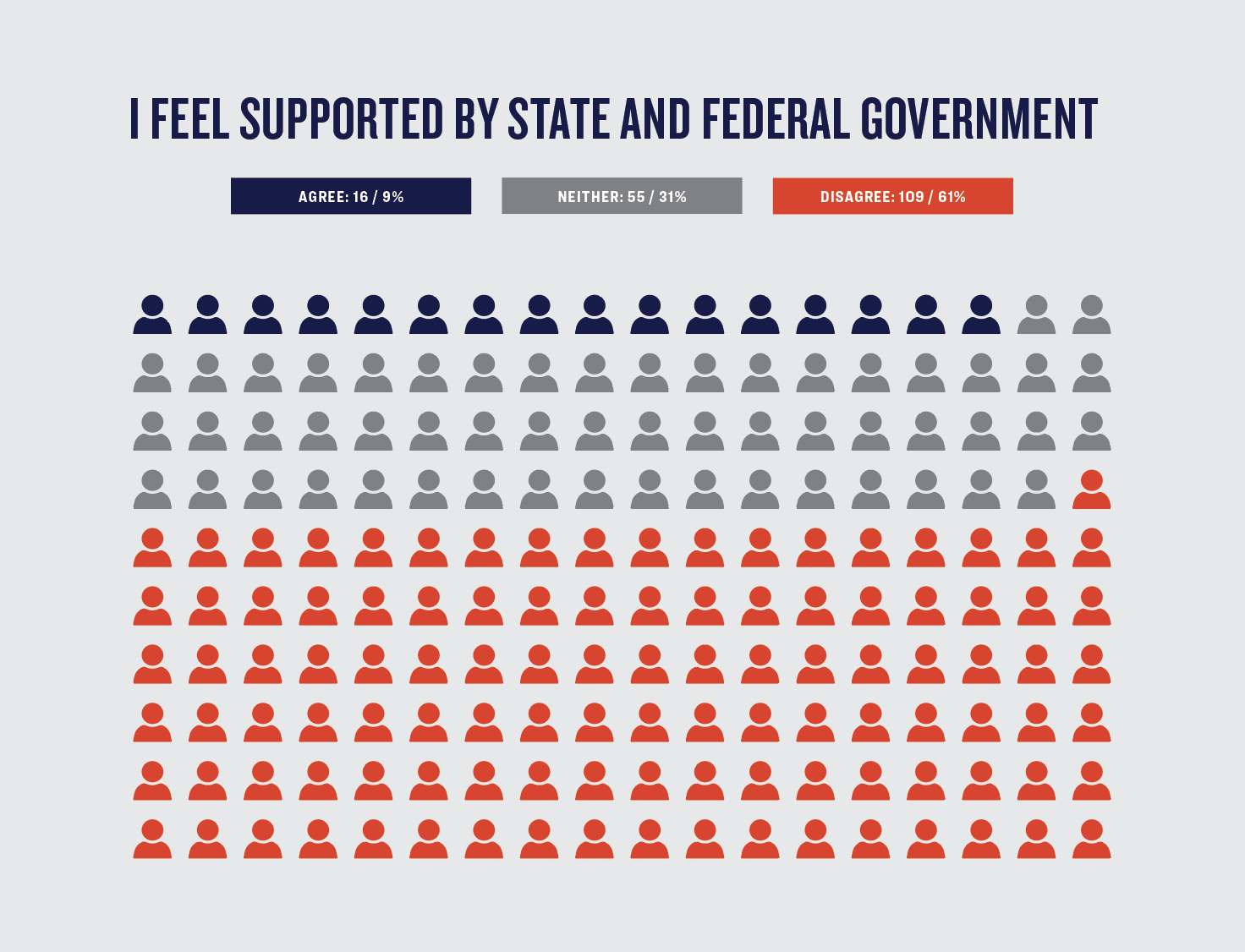

CVI workers were more likely to report feeling unsupported by government actors, particularly government actors above the local level: 56% of respondents disagreed with the statement that their local government adequately supports and funds their work. Feelings of support from state and federal governments were even lower, with 61% of workers indicating that they did not agree that their state and federal governments adequately supported or funded their work.

A lack of professional respect from law enforcement and government agencies was also reflected in the focus group of senior managers. Several participants indicated that government and law enforcement officials did not fully understand or value the work CVI workers do, which led to the work being de-prioritized for funding. Susan Lee of Chicago CRED indicated that her experience with government was that there was “zero knowledge of what’s going on on the ground” when it came to CVI work.

Danny Zamora, program manager at Crossroads in Los Angeles, shared that “politicians are more open to supporting law enforcement versus a street-level, community-based effort,” adding “I think there’s always been a tug-of-war type of battle between law enforcement and interventions.”

Access to Resources for CVI Work

Respondents were also asked about their access to the resources they need to do their jobs, including both concrete resources, like training, and more intangible resources, like time. In general, workers indicated that they could access the more tangible resources they needed, but felt they lacked the time and staffing to work most effectively in their communities.

More than two-thirds (68%) of workers reported receiving adequate training for their role, with 21% of workers neither agreeing nor disagreeing that they received adequate training, and only 11% reporting they did not feel they got enough training. Workers with higher levels of education were more likely to indicate that they did not receive enough training for their role.11

In addition to feeling adequately trained for their roles, the majority (84%) of workers felt they had access to the resources they needed for their clients, including job opportunities, food, housing, and mental health services.

One other indication of tangible resources in our survey concerned access to personal protective equipment like masks and hand sanitizer during the early phases of the pandemic (March 2020 through June 2020). Sixty percent of workers reported that they had adequate access to these resources during this time period.

However, despite access to the physical resources needed for their roles, the vast majority (93%) of respondents indicated that there were not enough outreach workers doing violence intervention work. Older respondents in particular were significantly more likely to report that there were not enough workers in the field.12 Additionally, many respondents indicated that there was high turnover in the field, with 43% of respondents reporting they had seen many coworkers leave the field and only 26% of respondents fully disagreeing that many coworkers had left the field.

It’s worth noting that participants in our management focus group offered slightly different perspectives on resources for workers, particularly regarding training. Many of these managers shared that their approach involved frequent training to keep workers updated on changes in the field. As Claudia Bracho of Los Angeles said, “We have to be constantly developing training and changing training because the streets are always changing.”

Members of the focus group agreed that there are opportunities to provide better, more comprehensive training. Kentrell Killens of the City of Oakland Department of Violence Prevention shared that the CVI workers and organizations need training that helps people deal with the trauma they see on the job, and that prepares them to “deal with the personal aspects of the work as well as the professional.”

Furthermore, many focus group participants indicated that there needs to be training that can provide distinct professional development opportunities, particularly for older workers, including opportunities to become outreach worker trainers and certified community health workers. Susan Lee, chief of strategy at Chicago CRED, also suggested a need for additional training for managers, saying, “It takes a very specific set of skills to be able to be a project director or a manager that is responsive to the needs of this workforce or violence dynamics.”

Additionally, the administrators in our focus group raised resource-related issues that were more specific to their roles managing funding for this work. Many participants expressed concerns that funding for this work does not always go to the organizations doing the work on the ground. Participants discussed the need for technical support, funding allocation support, and assistance with evaluations of the work to help direct funding appropriately and ensure that organizations have the infrastructure to distribute this funding.

CVI Worker Trauma

Finally, our survey asked several questions about the traumatic experiences of CVI workers, both in their professional roles and in their lives prior to becoming outreach workers. Importantly, the vast majority of workers indicated that they were fulfilled by their work: 99% of respondents agreed that being able to help people at work gave them satisfaction, with 73% strongly agreeing with this statement.

However, despite high job satisfaction, many CVI workers reported that they were affected by the emotionally draining nature of CVI work, with 53% of respondents agreeing that the trauma of people they helped at work had some effect on them. Additionally, 56% of respondents said that within the last 30 days, they had been less productive at work due to sleep loss from the trauma of their work at least some of the time.

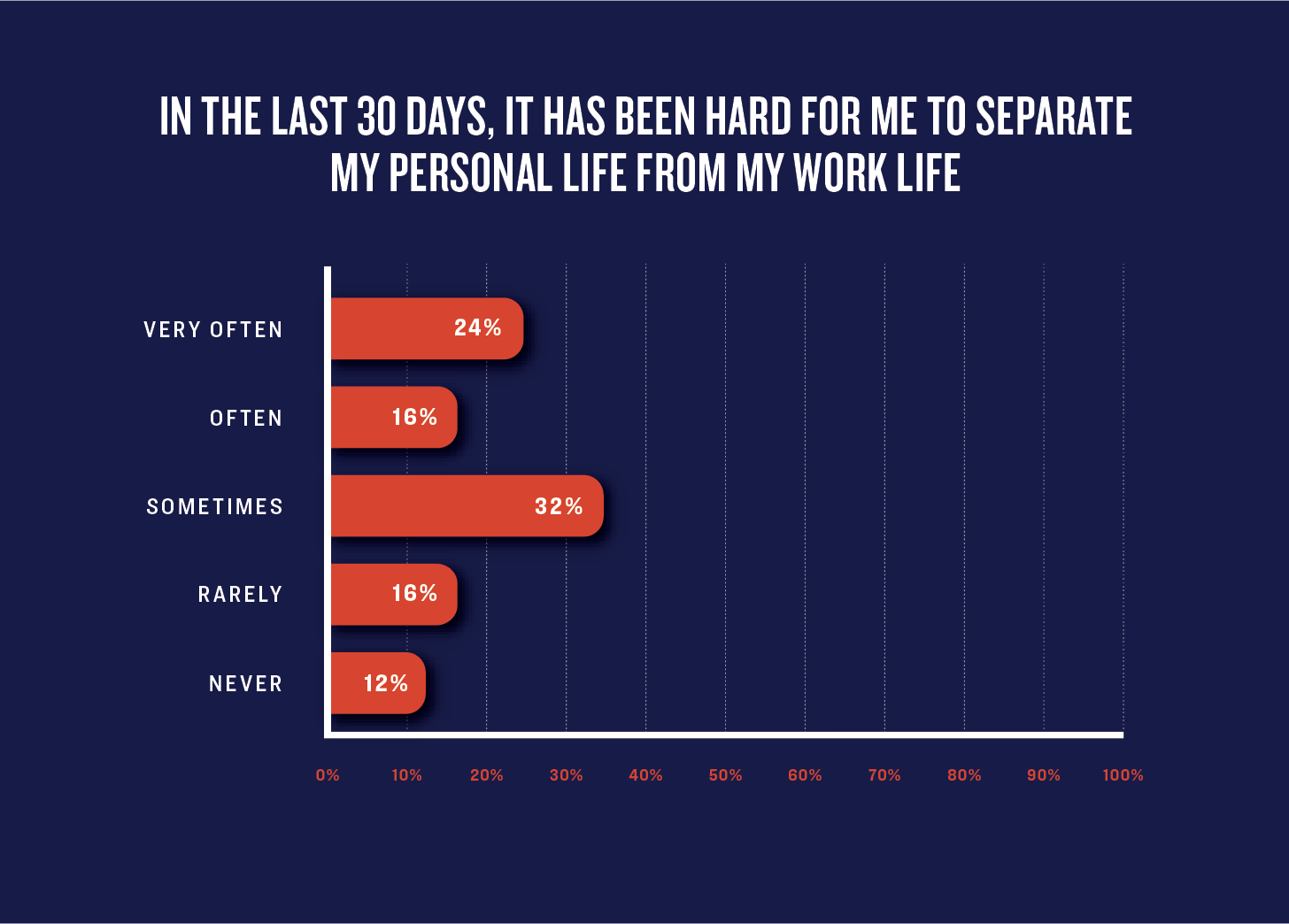

Furthermore, nearly three-quarters (72%) of workers reported that it had been difficult at least some of the time over the last 30 days to separate their work and personal lives, with nearly a quarter (24%) saying that they very often found this separation difficult. It’s important to note that 42% of CVI workers indicated that they believe that people may die if they don’t show up to work, suggesting an extremely high emotional investment in their jobs and the communities they serve. One in five (20%) workers worried all or most of the time about their ability to continue doing the emotionally draining work required of their role.

CVI workers also had high scores on the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K6), a standardized tool to measure nonspecific psychological distress, such as a diagnosable anxiety or depressive disorder severe enough to cause functional limitations and to require treatment.13 A standard cutoff score of 13 or higher on the K6 has been used to identify persons with serious psychological distress, and previous research has found a strong link between high psychological distress and premature mortality, as well as other negative health outcomes.14

Eighty-three percent of workers in our sample had a score of 13 or higher on this measure, with an average score of 17, indicating a severe level and risk of psychological distress. Furthermore, nearly a quarter (23%) of workers reported being in poor or fair physical health, which may reflect, in part, the high levels of psychological distress, given that poor physical health and poor mental health are highly interrelated.15

Importantly, in addition to the trauma respondents reported experiencing on the job, many workers experienced high levels of trauma and adverse experiences prior to their role as an outreach worker. Accordingly, many of the traumatic exposures from CVI work may amplify existing trauma. For example, as is consistent with the program approaches of many CVI work models,16 the majority (87%) of respondents had previously spent time in jail, prison, or a juvenile detention center.

Most respondents also had previous personal experience with gun violence prior to their role as a CVI worker: 93% of workers indicated that they had directly witnessed gun violence before becoming a paid CVI worker. Additionally, 56% of respondents reported that they themselves had been the victim of gun violence themselves before becoming a paid CVI worker.17 Fifty-two percent said that a family member had been a victim of gun violence, and 56% said a friend had been a victim of gun violence.

Many outreach workers also reported high levels of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). The standard ACEs measure includes child maltreatment, household dysfunction, and other critical issues known to impact children negatively.18 In fact, a vast body of literature has shown that experiencing these adverse experiences in childhood increases the risk of violence victimization and perpetration in adulthood and the likelihood of experiencing chronic mental and physical health conditions.19

Ninety-four percent of CVI workers in our sample reported experiencing at least one adverse childhood experience, and 69% reported experiencing four or more adverse childhood experiences. The average total ACEs score in our sample was 4.7 out of 8. ACEs scores among our sample of CVI workers were much higher than reported in the general population, where 36% of people have no ACEs and only 12.5% have four or more ACEs.20 However, we did find that ACE scores among our sample of CVI workers were comparable to published data on specific vulnerable populations, where research has found average ACEs scores between 4.8 and 4.9.21

Scores were generally high within most categories of adverse childhood experiences: 82% had lived with people who had problem alcohol or drug use, 73% of workers reported experiencing emotional abuse in childhood, 67% had an incarcerated family member, 61% reported physical abuse, 56% witnessed domestic violence, and 51% had divorced parents. The number of workers who reported that they experienced sexual abuse as a child or that they lived with someone who had a mental illness were lower—25% and 47%, respectively—but still significantly higher than general population samples.22

Part-Time Workers

Given our sampling methodology, the small sample size (n=20), and the diversity in experience among part-time workers, only limited conclusions can be drawn about this group. Part-time workers were also not equally distributed geographically, with 75% of workers located in Los Angeles.

The average age of part-time workers in our sample was 43; 70% of part-time workers were male. Pay varied significantly within this sub-sample of workers due to their status as part-time employees.

Ninety percent of part-time workers indicated that they received all the training needed to do their jobs; 85% of these workers agreed that they were able to connect clients to the resources and services they need.

Eighty-five percent of part-time workers had at least occasional worries about losing their jobs due to a lack of organizational funding. Nevertheless, 95% of part-time workers in our sample said they felt supported by their organizations in the last 30 days, and 95% of these workers reported getting satisfaction from being able to help people in their role. Fifty percent of part-time workers indicated that they were impacted by the trauma of those they helped in their role.

Photo courtesy of Chicago CRED

Recommendations

Identified Issue #1: CVI workers suffer from unequal pay and inadequate fringe benefits.

Recommendation: Baseline pay for CVI workers should start at $45,000 annually (with adjustments based on cost of living and overtime compensation), in addition to medical, dental, life insurance, and retirement benefits.

Street outreach work is a calling: those drawn to it are not in it for the money, and almost universally report high levels of job fulfillment despite relatively low wages. However, a higher average pay for the field is sorely needed, both to reflect the inherent value of the work and the risks involved, as well as to help address commonly reported issues of retention, recruitment, and negative health impacts on intervention workers. It’s telling that nearly 75% of the street outreach workers surveyed for this report said they had to work one or two additional jobs.

Eighty percent of full-time frontline intervention workers surveyed reported earning a salary of $50,000 per year or less. The average salary for a police officer in California, where roughly half of surveyed outreach workers reside, is twice that much.23 Moreover, as the International Association of Chiefs of Police points out on its website, base pay for many police officers is “often augmented by a variety of special pays,”24 including overtime, extra pay for shifts worked on weekends or nights, and vehicle and equipment allowances. Such augmentations are not typically available to street outreach workers, even while 87% reported that they work additional hours beyond their regular work schedule at least once a month, and more than half reported working additional hours at least a few times each week.

In terms of benefits, two-thirds of intervention workers indicated that their employer provided retirement benefits, and 60% reported receiving life insurance from their employer. However, given that such benefits are provided nearly universally in policing—in the City of Chicago, for example, 100% of incoming officers are automatically enrolled in a city-funded life insurance plan—these numbers need to be dramatically increased in the field of street outreach work.

Worker compensation varies widely across CVI organizations, ranging from $2,000 monthly stipends to a more livable wage of $40,000 per year plus benefits. Chicago CRED is one of few organizations that implements a standardized salary structure for its more than 90 employees. Street outreach staff, who make up about a third of CRED’s workforce, have a starting salary of $45,000 or more, depending on experience. Life coaches, whose roles include more case management, generally start at $50,000, while the salaries of leads and supervisors begin at about $55,000. CRED employees also receive an annual cost of living adjustment.

In addition to a salary, CRED staff are provided medical, vision, and dental insurance, including access to mental health care. Workers also receive limited life insurance benefits and are issued a laptop computer after they are hired.

Higher annual salaries and benefits will help address one of the core issues experienced by organizational leaders and survey participants alike: high rates of turnover and burnout, combined with difficulty in recruiting a new generation of frontline workers. Ninety-three percent of surveyed respondents indicated that there were not enough outreach workers doing violence intervention and prevention work, while 43% reported they had seen “a lot” of coworkers leave the field. Providing pay and benefits that reflect the enormous value and inherent risk of frontline intervention work is critical for organizations to recruit and retain individuals with the specialized skill set necessary to do this lifesaving work.

Identified Issue #2: Many violence intervention workers are dealing with their own untreated trauma while being regularly exposed to vicarious trauma at work.

Recommendation: Organizations employing CVI workers must institutionalize trauma-informed systems of self-care and ongoing support for their employees.

A large number of violence intervention workers bring their own direct experiences of trauma to the job: more than 90% of those surveyed for this report had witnessed an act of gun violence prior to starting their current position, 56% reported being the direct victim of gun violence, and more than half said that a family member or a friend had been the victim of gun violence. In addition, 87% of those surveyed were previously incarcerated. Not surprisingly then, more than 80% of workers met or exceeded the commonly used threshold for a high score on a standardized measure of psychological distress.

To address this, self-care practices must be embedded in the daily and weekly operations of CVI organizations. This may include educating staff about the basics of trauma and the role of self-care; providing access to culturally competent mental health services as well as non-traditional healing methods; encouraging the creation of self-care plans, including scheduled and unscheduled days off; and rotating schedules to periodically remove staff from crisis response duties. As a starting point for organizational leaders, the Health Alliance for Violence Intervention offers a useful resource titled “Best Practices for Supporting Frontline Violence Intervention Workers.”

Exemplifying this commitment to supporting staff wellness, the violence intervention organization Boston Uncornered25 hired a full-time clinical manager whose sole role is to support the well-being of the intervention staff. The clinical manager is not in a formal therapist-client relationship with staff, but rather is there to provide generalized support and make referrals to more formalized care when appropriate. In addition to regular health benefits, Boston Uncornered covers the cost of co-pays for outreach staff to receive mental health services. They also offer staff unlimited time off and unscheduled days off to give workers a chance to recharge after particularly stressful periods.26

Embedding this support for frontline staff should be a universal minimum standard for violence intervention organizations, meaning that funding should be structured in a way that intentionally supports and encourages self-care. As a staffer for Boston Medical Center’s Violence Intervention Advocacy Program27 stated in a report published by Healing Justice Alliance, “There should be a section in all grants, similar to indirect costs, goals, and objectives, that mandates funding for staff self-care. It is absurd to think that we keep adding expansion of services and quality client care, and aren’t investing in supporting the health and wellness of our frontline staff.”28

Identified Issue #3: A lack of uniform training and professional standards hamper the field of violence intervention.

Recommendation: A national certifying entity should implement minimum standards of training and experience for CVI workers.

The field of community violence intervention lacks a certifying body at the state or national level. As a result, training and professional standards differ from city to city and program to program. Street outreach workers deserve recognition of their important and hard-earned skill set, and communities also deserve trained intervention workers who are as effective as possible and are minimizing risk for themselves and their clients. While our sample felt that they largely received enough training to do their work, our focus group participants expressed a desire for standards in order to respond to the dynamic and ever-changing nature of CVI work.

At a local level, the cities of Chicago and Los Angeles have both created standards for their workers that provide examples of potential protocols to follow. In Los Angeles, the city-funded Urban Peace Academy implements minimum qualifications and training standards, offers a tiered professional development track, and enforces standards of conduct and practice through a Professional Standards Committee.29 These standards of conduct include ongoing education, the responsible use of social media, and staying within an individual’s “license to operate.”30 Chicago CRED maintains a list of 10 working competencies, which include, for example, “employ critical thinking skills to inform professional decisions” and “promote human rights and social justice,” alongside 14 working standards, which include guidance such as “establish a professional understanding with law enforcement” and “take care yourself so you can take care of others.”

At the national level, the Health Alliance for Violence Intervention (the HAVI) maintains universal minimum standards for its more than 40 member programs. These standards include minimum lengths of service provision to clients, staff training, staff members who reflect the communities they are serving, and a commitment to trauma-informed support for both clients and staff.31 The HAVI also conducts the only national certification program for hospital-based violence prevention professionals.32

Additionally, updated training should be required on a regular basis—for example, the California Board of Behavioral Sciences requires licensed clinicians to undergo 36 hours of continuing education during each two-year license renewal period.

Identified Issue #4: Smaller violence intervention organizations may lack the capacity to leverage public grants.

Recommendation: The government should pass federal funding to smaller community organizations through intermediaries set up specifically for this purpose.

Due to years of a lack of attention, understanding, and investment, many organizations—especially smaller groups—lack the infrastructure to apply for and successfully secure formal grants. One potential answer to this problem is for governments to work with “intermediaries” like the Latino Coalition.33

The Latino Coalition for Community Leadership is an intermediary that finds, funds, forms, and features nonprofits meeting the needs of individuals and families in marginalized communities. The Latino Coalition provides technical assistance, capacity-building, and robust administrative infrastructure that allow grassroots and small nonprofits the ability to develop, scale, and manage growth while demonstrating performance, stewardship of resources, and return on investment.

In a 2021 Giffords webinar on the subject of intermediaries,34 Hassan Latif, founder of the Second Chance Center in Colorado, described how the Latino Coalition partnered with him to take his organization, which helps formerly incarcerated individuals reestablish their lives, from one he ran out of the back of his car to a multi-million dollar nonprofit.

“We were able to build an infrastructure with the help and the guidance of the Latino Coalition that made our growth something that we weren’t crushed beneath,” recalled Latif. “That budget seems large now, in relative terms, but if we had been given that kind of money earlier on in our existence it probably would have served to crush us as an organization as opposed to supporting us.”35

Local, state, and federal policymakers need to pair increased investments in the CVI field with increased support for organizational capacity in order to meaningfully leverage that investment. Intermediaries and grants specifically designed to expand capacity through training and technical assistance are important ways to help make that happen. In our focus group with CVI workers, Danny Zamora echoed the need for intermediaries, saying “I think one of the things we’ll need is foundations… intermediaries that will [be] like a middle person and back us up financially.”

Identified Issue #5: There is currently a lack of awareness and financial support from local, state, and federal governments.

Recommendation: The CVI field needs to make a concerted effort to raise awareness of the importance of this work.

Fifty-six percent of those surveyed for this report felt that their local government was not adequately supporting and funding their work, and 61% indicated that this was also true of state and federal governments. A lack of government support and funding was also a key theme in our focus group. As Giffords has documented in multiple reports, only a small handful of states provide any amount of support to community violence intervention work, and most of the existing investments are extremely small. This has also been true at the federal level, where direct funding for violence intervention work has traditionally been in the low millions of dollars, compared to the billions spent annually on law enforcement approaches to public safety.

Fortunately, this is starting to change, but only as the result of intentional organizing, advocacy, and coalition-building. In California, for example, the state’s primary investment in street outreach and violence intervention work comes from its Violence Intervention and Prevention grant program (CalVIP). The CalVIP Coalition, a statewide group of practitioners, advocates, city leaders, and researchers, has worked together for several years to raise the profile of intervention work by publishing opinion pieces by intervention workers,36 holding lobby days at the state capitol,37 and hosting events around the state for frontline workers to share their experiences.38 In 2021, the CalVIP Coalition successfully advocated for a statewide investment of $227 million over the next three years, up from a yearly investment of just $9 million.

It’s no coincidence that increased public support for the CVI field is happening where organized coalitions are demanding change: new investments in Pennsylvania,39 Virginia,40 Connecticut,41 Maryland,42 New York,43 as well as at the local and national levels, are the result of work by organized CVI coalitions. There is also a role for governments to play in supporting this progress: in the domestic violence field, the federal government funds statewide DV coalitions that share best practices.44 It should do the same for the community violence field.

All of this is a symptom of a larger issue: in addition to policymakers, the general public also remains largely unaware of intervention work as a solution to violence. CVI organizations and their advocates should engage in coordinated campaigns to inform and educate Americans, making use of myriad strategies and resources, including white papers, books, documentaries, op-eds, social media campaigns, community events and town halls, press conferences, public service announcements, presentations, and legislative hearings.

Identified Issue #6: There is currently a lack of local infrastructure to support and develop violence intervention organizations.

Recommendation: Establish Offices of Violence Prevention to provide funding, support, and training for the violence intervention field at the local and state levels.

Many of the issues identified above—the need for standardized training, more support from public funding sources, and capacity building for the CVI field—can be improved with the support of local and state infrastructure designed to address these concerns. In more and more localities and states, this is happening through the creation and expansion of Offices of Violence Prevention (OVPs).

At the urging of community members and advocates, Los Angeles created the Mayor’s Office of Gang Reduction and Youth Development (GRYD) in 2007.45 With an annual budget of approximately $30 million, GRYD is a centralized entity that has helped Los Angeles develop uniform standards of data collection and evaluation for violence intervention work, fostered standardized training for frontline workers, and helped raise the profile of this work. With the support of GRYD, Los Angeles reached a decades-low number of homicides and shootings in 2019, with a homicide rate not seen in the city since the early 1960s.46

In Oakland, California, a voter-approved ballot initiative helps fund the city’s recently established Department of Violence Prevention, which is charged with implementing a citywide violence reduction strategy with the participation of community members, passing public funding through to a network of community-based organizations, and coordinating an inter-agency response to violence. Recognizing the vital importance of lifting up community-based, trauma-informed approaches to public safety, the City of Oakland doubled down on its investment in the Department of Violence Prevention in the summer of 2021.

The OVP model is on the rise, with more than 20 cities joining the launch of the National Offices of Violence Prevention Network in early 2021.47 However, many more cities need to develop OVPs to organize and develop the capacity of organizations and individuals engaged in violence intervention work. The National OVP Network, which provides technical assistance and peer support, is a good starting place for cities looking to create this vital infrastructure. As the OVP model expands, it’s critical for hired staff to be as diverse as possible, reflect the communities being served, and have lived experience with violence intervention work.

In our focus group, Susan Lee said of an Office of Violence Prevention, “It has to have power and authority, first of all. It has to be tied to some sort of decision-making structure… because in the end, it’s about protecting those resources.”

Many of the issues identified above come down to two main problems: a lack of awareness of violence intervention work, and a lack of public investment. Giffords is committed to working with partners around the country to address both as quickly as possible. It’s time for the brave individuals on the front lines of community violence to receive the attention and support they so greatly deserve.

Conclusion

Policies to reduce violence are often spoken about in terms of numbers: homicide rates going up or down, line items in a budget that decide whether or not a particular program can keep its lights on. This report is no exception—we used survey responses to glean information about where resources are most needed, and we hope that organizations and individuals with the power to make important funding decisions do the same.

But at its core, reducing and even ending violence is about human beings. If we can disrupt the cycle of retaliatory violence and help an individual choose to heal rather than pick up a gun—and avoid spending time in prison in the process—we have succeeded. That is what violence intervention work, fundamentally, aims to do: empower human beings with lived experiences of violence to offer traumatized and trapped young people another way forward.

As mentioned earlier in this report, a CVI worker was shot and killed while we were conducting our survey: Kenyell “Benny” Wilson, who worked with Baltimore’s Safe Streets program for more than eight years and is survived by his wife and 11 children. In March 2021, we published a blog post paying tribute to a number of other CVI workers who died in gun homicides over the past year, including Caleb Reed, shot months before his senior year of high school; Lorraine Thomas, who used Zoom to broker a truce between warring groups in the early months of the pandemic; and Dante Barksdale, a towering figure in the Baltimore CVI community who appears in the cover photo for this report.

We hope to honor the memories of these individuals by making CVI work safer and more effective. As gun violence continues to surge in cities across the country, we must not abandon this proven and promising work and the heroic individuals responsible for it. Instead, we must re-commit to them and the communities they serve.

As a gun violence prevention organization, we know that meaningfully addressing our nation’s gun violence epidemic is not just about strengthening our gun safety laws. We also have to fund community violence intervention work—not in fits and starts, but sustainably, over the long term. These funding decisions must be informed by the individuals doing this critical, dangerous work day in and day out. We hope that this report is useful in securing funds for these programs and supporting the workers whose experiences are reflected in its pages.

Acknowledgments

Without the following organizations and individuals, this report would not have been possible. Below is more information about Chicago CRED, the Mayor’s Office of Neighborhood Safety and Engagement in Baltimore, the City of Oakland Department of Violence Prevention, and the Urban Peace Institute in Los Angeles, as well as the individuals who served as the report’s co-authors and our primary points of contact within each of these four organizations.

Chicago CRED

The Chicago CRED program, founded in 2016 by former US Education Secretary Arne Duncan, is committed to reducing violence in the city’s most impacted communities. CRED hopes to achieve an ambitious 80% citywide reduction in shootings and homicides by providing holistic wraparound services to those at highest risk for involvement with violence.

CRED’s strategy relies on a detailed group-by-group analysis that ensures services reach men and women in Chicago at highest risk for engaging in violence. According to research from Northwestern University, CRED participants are 43 times more at risk of injury or death by a firearm than the average Chicago resident, and are nearly three times more likely to be shot than other residents in CRED outreach areas.

The program leverages outreach staff with lived experience and personal connections to the community to diffuse imminent conflicts and recruit “street-active” men and women to participate in CRED programming. CRED participants gain access to life coaches who act as mentors and advocates to provide participants with support and stability. They are also offered comprehensive employment training that aims to teach them the skills necessary to transition to the legal economy, as well as trauma-informed counseling.

Further research from Northwestern University’s Institute for Policy Research suggests that participants in Chicago CRED are about 50% less likely to be injured or killed with a firearm or arrested for a violent crime compared to a matched group of young men who were not part of CRED or any known outreach effort.

CRED also plays a key role in coordinating Chicago’s community-based violence reduction efforts; strengthening and building the capacity of community-based groups; and advocating for federal, state, and local governments to adequately resource such initiatives. As of the 2021 legislative session, the state of Illinois provides the City of Chicago with over $60 million in funding to support CVI work.

Melvyn Hayward, Chicago CRED

Melvyn is Head of Programs at Chicago CRED, a nonprofit founded in 2016 by former Secretary of Education Arne Duncan and Laurene Powell-Jobs of Emerson Collective. The singular mission of Chicago CRED is to achieve a transformational reduction in violence in Chicago. As the head of programs, Mel oversees all of CRED’s outreach and programming efforts, in addition to maintaining relationships with key programming partners on the West and South Sides of Chicago.

Prior to joining CRED, Melvyn was the executive director of HELPER Foundation, an organization he founded in 1999. HELPER is a non-profit 501 (c)3 organization that was originally established to provide gang intervention and prevention services. During its inception, the founders came to believe that “community intervention” services are needed now more than ever to combat gang-related violence, the destruction of our communities, and the loss of our young people to the lure of economic depravity.

Additionally, Mel has traveled to 30 cities throughout the US, training outreach workers, developing best practices, and providing technical support to several violence reduction agencies.

Susan Lee, Chicago CRED

Susan K. Lee is the Chief of Strategy and Policy at Chicago CRED, a nonprofit founded in 2016 by former Secretary of Education Arne Duncan and Laurene Powell-Jobs of Emerson Collective. As the Chief of Strategy and Policy, Susan works on building a strong community-based violence intervention infrastructure, increasing public and philanthropic investment into communities most impacted by violence, and developing research-based evidence for comprehensive public health approaches to violence reduction.

Prior to being at Chicago CRED, Susan served as the City of Chicago Deputy Mayor of Public Safety. In that role, she oversaw the Chicago Police Department, Chicago Fire Department, OEMC, COPA, and the Police Board. In her role, she focused on implementing CPD’s reform efforts under the consent decree; developing the City’s comprehensive violence reduction strategy, “Our City, Our Safety”; and implementing City’s investment into community violence intervention through the newly established Office of Violence Reduction.

Before working in Chicago, Susan worked nationally in many jurisdictions, including Los Angeles, Oakland, Sacramento, and Memphis, to develop and support community-based interventions and relationship based policing initiatives. Most notably, Susan is the co-author of the 2007 “Call to Action” which was adopted by Los Angeles as blueprint for the city’s violence reduction strategy, resulting in the creation of the Mayor’s Office of Gang Reduction and Youth Development, LAPD’s Community Safety Partnership, and sustained investment into community-based violence intervention resources.

Susan holds a BA and JD from UC Berkeley and is a member of the California State Bar, as well as the author of several publications on immigration, racial justice, and best practices in violence reduction.

The following organizations worked with Giffords and Chicago CRED to administer surveys in Chicago:

- Institute for Nonviolence Chicago

- Alliance of Local Service Organizations

- UCAN

The following individuals also helped coordinate surveys in Chicago:

- Jalon Arthur—Director of Strategic Initiatives, Chicago CRED

Photo courtesy of Chicago CRED

Mayor’s Office of Neighborhood Safety and Engagement—Baltimore

Baltimore City is grappling with multiple public health crises—not only is it struggling with the global COVID-19 pandemic, but it is also facing the local epidemics of opioid overdoses and gun violence. Since 2015, the city has seen an excess of 300 homicides per year—the overwhelming majority of which are gun-related. The over-reliance on police to reduce violence and strengthen community safety has not only failed to yield sustainable results; it has also come at an extremely high social cost to many of the city’s most vulnerable communities.

Almost immediately after taking office in December 2020, Mayor Brandon Scott established the Mayor’s Office of Neighborhood Safety and Engagement (MONSE) and charged the office with leading citywide efforts in addressing crisis levels of gun violence today, while also addressing broader social determinants of health for a safer and more equitable Baltimore tomorrow.

On July 23, 2021, MONSE released the City’s five-year Violence Prevention Plan—an all-hands-on-deck strategy that calls for beefing up investments in the city’s violence intervention efforts, particularly street outreach. This includes substantial investments to strengthen and expand Baltimore’s flagship street outreach program, Cure-Violence-based Safe Streets, which currently employs 86 street outreach workers across 10 Safe Street sites.

The plan also commits the City to deepening its commitment to programs that pair street outreach with intensive case management or life coaching as well as building its intervention infrastructure to serve men over the age of 24, who account for roughly 70% of gun violence victims in Baltimore City. This promise was fulfilled when MONSE awarded a $1.2 million contract to Youth Advocate Programs, Inc.

2021 has been a year of terrible tragedy for Safe Streets and Baltimoreans at large, with the loss of a leader, Dante “Tater” Barksdale, and an outreach worker, Kenyell “Benny” Wilson. Shaken, grieving, yet undeterred, Baltimore City has redoubled its commitment to supporting its street outreach partners and, above all, their frontline workers.

Shantay Jackson, Mayor’s Office of Neighborhood Safety and Engagement

Shantay Jackson, the Director of the Mayor’s Office of Neighborhood Safety and Engagement, is responsible for addressing violence as a public health issue, serving as the accountability partner for all city agencies and local, state, and federal partners, delivering public safety policy recommendations, and conducting meaningful engagement with Baltimore City’s neighborhoods in the work of coproducing safety.

Prior to being appointed to Mayor Scott’s cabinet in late 2020, Shantay served as the Executive Director of the Baltimore Community Mediation Center, an organization dedicated to reducing interpersonal conflict and community violence in Baltimore City by increasing the use of non-violent conflict resolution strategies. During her time there, Shantay expanded the organization’s reach by rolling out a three-component Police & Community Program, introduced community listening tours, and provided moderation and facilitation services to grassroots organizations and city agencies. She was also federally appointed to serve as a member of the BPD Consent Decree Monitoring Team.

Shantay also has an extensive background in the private sector environment, serving with T. Rowe Price and Brown Advisory for almost twenty years. Shantay has a deep personal belief that purpose-driven work means doing ancestor work while you are alive.

The following organizations worked with Giffords and the Mayor’s Office of Neighborhood Safety and Engagement to administer surveys in Baltimore:

- Safe Streets

The following individuals helped coordinate surveys in Baltimore:

- Jeremy Biddle—Special Advisor, Mayor and Police Commissioner

- Rashad A. Singletary—Associate Director of Gun Violence and Prevention, Mayor’s Office of Neighborhood Safety and Engagement

- Anisha Thomas—Deputy Director-Safe Streets Baltimore, Mayor’s Office of Neighborhood Safety and Engagement

- Gardnel (Hamza) Carter—Community Liaison Officer, Safe Streets Baltimore

Photo courtesy of the Mayor’s Office of Neighborhood Safety and Engagement

Oakland Department of Violence Prevention

Oakland’s Department of Violence Prevention (DVP) pursues a public health approach to reduce violent crime by leveraging community-led violence prevention and intervention strategies focused on individuals, families, and communities most impacted by violence. The city’s violence reduction strategy is credited with helping reduce gun-related homicides in the city by 31% from 2010–2017. Moreover, two years after engaging in hospital-based intervention and temporary, emergency relocation programs, DVP participants’ rate of violent re-injury dropped from 59% to 15%.

The DVP’s mandated goals include:

- Reducing homicides and gun-related violence

- Reducing incidences of domestic violence and addressing and reducing the commercial exploitation of children

- Reducing trauma experienced by families connected to unsolved cold cases

- Reducing community trauma related to intense violence

To achieve these goals, Oakland’s DVP and its partners respond to incidents of violence in real time and provide trauma-informed support services to survivors and their loved ones. The program leverages “street-credible” outreach staff to engage those most involved in violent activities with mentorship, life coaching, and employment supports, among other services. The department also helps foster community healing through restorative practices, workshops, and public events to reclaim neighborhood spaces.

In addition to providing direct services, support, and community engagement, the DVP plays an important role in coordinating the city’s violence reduction strategy, which involves managing a robust citywide network of community-based services providers. Together, the DVP and its funded network of providers serve and support annually over 3,000 individuals who are most at-risk for being involved in intense violence.

DVP activities have historically been funded with proceeds from local tax measures, passed by Oakland residents in 2004 and 2014, and has leveraged funds from state and federal sources such as the California Violence Intervention and Prevention (CalVIP) program, as well as federal Department of Justice and Housing and Human Services grants. In June 2021, Oakland’s City Council voted to double the DVP’s budget by investing general purpose fund dollars to support the strategy for the first time.

With the recent increase of funds, Oakland’s DVP doubled the number of citywide community-based violence Interrupters who are tasked with responding to homicides and shootings in real-time and supporting impacted victims and families through a “triangle approach” that incorporates and coordinates around-the-clock crisis response efforts of DVP, law enforcement, and community-based non-profit organizations. In addition, DVP initiated citywide teams of Community Ambassadors who support neighborhood efforts to prevent violence, engage vulnerable and impacted residents, and promote peace and community wellness through street outreach, community events, and resource brokerage.

Chief Guillermo Cespedes, Oakland

Guillermo Cespedes is a violence prevention and intervention expert with over four decades of experience at the community, municipal, national, and international levels. He worked in Oakland for 19 years in direct services with families experiencing domestic violence, alcoholism, drug addiction, and chronic illness. In 2009 he was appointed Los Angeles’s Deputy Mayor/Director of the Office of Gang Reduction and Youth Development (GRYD). During his tenure (2009–2014), Guillermo guided the implementation of the city’s comprehensive strategy, touted with reducing nine categories of Part 1 crimes by nearly 50%.

He is the architect of the 24/7 Triangle Incident Homicide Response, Summer Night Lights, and the GRYD Family Case Management Model. Guillermo also spearheaded the creation of the Los Angeles Violence Intervention Training Academy.

In 2014 Guillermo joined Creative Associates International and in 2016 moved to Honduras as Deputy Chief of Party for USAID. While in Honduras, he also provided on-the-ground technical assistance to violence prevention programs in Mexico, Honduras, El Salvador, St Lucia, Guyana, St. Kitts, and Nevis. In addition, Guillermo guided the adaptation of gang prevention strategies to the reduction of extremist groups in Tunisia, North Africa. In September 2019, he returned to Oakland as Chief of the Department of Violence Prevention. Guillermo holds a Master’s Degree in Social Work from Columbia University.

Peter Kim, Oakland

Peter Kim is a senior consultant at Bright Research Group in Oakland, California, who has overseen the design and implementation of violence prevention, intervention, and youth development programming as a direct service provider, manager, and director in both community nonprofit and local government settings for over 20 years. Peter has extensive experience with community-based grantmaking, applied research and evaluation, and program design in the areas of gun violence and gender-based violence prevention using a public health approach.

For the past seven years, Peter served as manager for the City of Oakland’s Department of Violence Prevention and has helped lead citywide strategic planning and grantmaking processes that prioritize investments in relationship-centered, healing efforts that lift up community-led alternatives to punishment and incarceration, grassroots capacity-building, leadership development, and cross-sector coordination. A dedicated advocate for social justice and racial equity, Peter holds Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees in Ethnic Studies and is currently pursuing his doctorate at UC Berkeley.

The following organizations worked with Giffords and the Department of Violence Prevention to administer surveys in Oakland:

- Youth Alive

- California Youth Outreach

- East Bay Asian Youth Center

- Communities United for Restorative Youth Justice

- Building Opportunities for Self Sufficiency

The following individuals helped coordinate surveys in Oakland:

- Anne Marks—Executive Director, Youth Alive

- Kentrell Gregory Killens—City of Oakland, Department of Violence Prevention

Photo courtesy of the Oakland Department of Violence Prevention

Urban Peace Institute—Los Angeles

The Urban Peace Institute (UPI) is a nationally recognized leader in the field of community safety, just policing, and systems reform to end violence and mass incarceration. For two decades, UPI has developed and implemented innovative solutions to address community violence and engage in system reform. In 2007, UPI pioneered a groundbreaking “Call to Action” report and worked in partnership with the City of Los Angeles and Los Angeles Police Department to effectively change the way Los Angeles deals with gangs and community violence.

UPI’s advocacy for a comprehensive violence reduction strategy resulted in the adoption of programs such as the Mayor’s Gang Reduction & Youth Development Office, Community Safety Partnership, and Summer Night Lights programs. Five years later, the homicide rate in Los Angeles was at its lowest since the 1960s, gang-related crime decreased by more than 15%, and gang-related homicides plummeted by 35%. An evaluation of Los Angeles’s peacemaking efforts demonstrates a significant decline in retaliatory homicides. When trained violence intervention workers respond to violent incidents, versus law enforcement alone, the rates of violent retaliations drop from 24% to 0.7%.

UPI established the nation’s first comprehensive training platform, the Urban Peace Academy, led by veteran intervention workers to train community intervention practitioners to respond to street-level violence. Since 2008, UPI has trained over 4,700 practitioners, community residents, public leaders, and law enforcement officers to work collaboratively utilizing a public health approach to achieve community safety across the nation.

UPI is member of the Los Angeles Violence Intervention Coalition (LAVIC), a group of 17 frontline community violence intervention agencies focused on ending the homicide epidemic in Los Angeles and across the country. The LAVIC has successfully advocated for over $33 million in funds to support community-based violence intervention efforts throughout the LA region.

Photo courtesy of Southern California Crossroads

Fernando Rejón, Urban Peace Institute

Fernando Rejón currently serves as executive director of Urban Peace Institute after building the organization’s agenda for the past decade. UPI works to reshape systems and develop safety and health strategies through national technical assistance and training. UPI also provides community lawyering services to end gang profiling and ensure police accountability, leads coalitions for justice reform and policy advocacy, shapes relationship-based policing approaches, and implements place-based initiatives to develop coalitions of leaders to reimagine public safety.

In 2008, Fernando began his work to build the Urban Peace Academy as a platform to train gang intervention/street outreach workers, law enforcement, community stakeholders, and public officials on implementing violence reduction strategies focused on redefining community safety and health. Over the years, he has trained thousands of leaders nationally on the role of gang intervention and the development of non-traditional community safety strategies. Fernando has trained and advised law enforcement agencies across the country on creating safety through innovative strategies that increase public trust and leverage investment in building neighborhood-level leadership.

Fernando holds a B.A. in Sociology and Communication Studies from the University of San Diego; an M.A. in Chicano Studies from California State University, Northridge; and a certificate from the Stanford Graduate School of Business Executive Program for Non-Profit Leaders.

The following organizations worked with Giffords and the Urban Peace Institute to administer surveys in Los Angeles:

- Homeboy Industries

- Southern California Crossroads

- Chapter TWO

- HELPER Foundation

- Advocates for Peace & Urban Unity (APUU)

- Resilient Agency

- Detours Mentoring

- Toberman Neighborhood Center

The following individuals helped coordinate surveys in Los Angeles:

- Karen Carter—Academy Coordinator, Urban Peace Institute

- Saul Garcia—Coalition Organizer, Urban Peace Institute

JOIN THE FIGHT

Gun violence costs our nation 40,000 lives each year. We can’t sit back as politicians fail to act tragedy after tragedy. Giffords Law Center brings the fight to save lives to communities, statehouses, and courts across the country—will you stand with us?

Spotlight

IN PURSUIT OF PEACE

Our report, How America’s Gun Laws Fuel Armed Hate, examines how our nation’s gun laws allow hate crime perpetrators to access weapons and carry out attacks.

Read More- Throughout this report, we’ll use the umbrella term “community violence intervention worker” to describe individuals with lived experience working with those at highest risk of violence. It’s a job that has different names in almost every city where these programs operate, from street outreach worker to violence interrupter, and many more.[↩]

- Based on Giffords Law Center analysis of FBI data. Federal Bureau of Investigation, Crime Data Explorer, last accessed Oct. 5, 2021, https://crime-data-explorer.app.cloud.gov/pages/explorer/crime/crime-trend.[↩]

- Id.[↩]

- Based on Giffords Law Center analysis of local police department data and FBI data.[↩]

- Based on Giffords Law Center analysis of local police department data.[↩]

- Id.[↩]

- Id.[↩]

- Employees who were not full time were defined as those working 30 hours or less per week or who were paid as contractors.[↩]

- Note that figures will not add to 100%. Some survey respondents elected not to answer questions on race and ethnicity, and respondents had the option to select multiple categories to more fully describe their own racial identity.[↩]

- X2 (5, N=180) = 12.577, p = 0.02769[↩]

- X2 (6, N=180) = 13.263, p = 0.03904[↩]

- X2 (6, N=180) = 14.521, p = 0.02433[↩]