Meet a Few People Behind Oakland’s Historic Progress on Gun Violence

Oakland, California, has cut homicides and nonfatal shootings in half since 2012. Meet some of the people who helped make that progress happen.

Our new report, A Case Study in Hope: Lessons from Oakland’s Remarkable Reduction in Gun Violence , details

Oakland’s incredible transformation, which came about due to a powerful partnership between community activists, law enforcement, city officials, and social service providers.

[How Oakland Cut Homicides In Half]

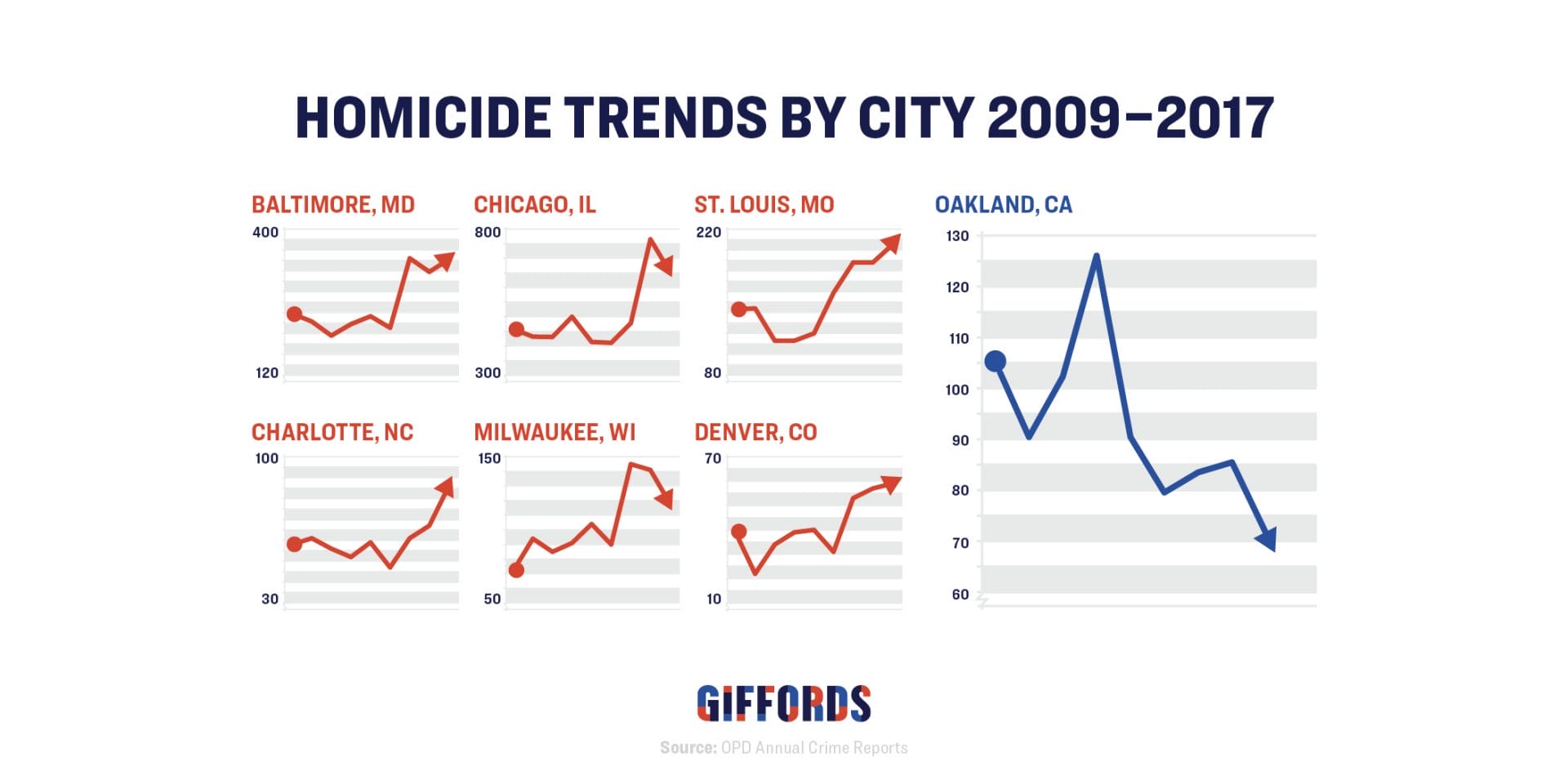

This years-long collaboration helped Oakland buck the trend of spikes in violence experienced by many other American cities during the same time frame.

Dozens of people played a critical role in Oakland’s success story, a number of whom are named in the report and many of whom are not. More than anything, credit for Oakland’s progress belongs to the young men who are choosing to put down their guns.

Below we highlight a few individuals who helped turn Oakland’s story around:

1. Reygan Cunningham

Today a senior partner at the California Partnership for Safe Communities, Reygan Cunningham formerly served as the program manager for Oakland Ceasefire, which combines community-based outreach and social services with narrowly targeted law enforcement actions. Reygan was tasked with doing a lot with a little in a city that had previously tried and failed to implement Ceasefire, lacking the resources and political capital to do so properly.

According to Reygan, Oakland Ceasefire is more tailored than strategies used by many other cities because it doesn’t focus on entire groups (or gangs), for law enforcement actions, for reasons of both capacity and fairness.

The social services provided through Oakland Unite, a division of the city’s Human Services Department, are also extremely tailored. Oakland Unite primarily serves individuals at the highest risk of becoming victims or perpetrators or violence. “The response used to be ‘they just need a job,’” Reygan said, “but many aren’t ready and some actually already have jobs, so that’s not their issue.”

“People’s highest need is safety, so you have to start there—a job doesn’t help if people are actively trying to kill you in the street.”

2. Oakland Unite life coaches

Oakland Unite’s life coaches work with the small percentage of Oakland’s population at highest risk for involvement with gun violence at any given time—an estimated 0.1%, or around 400 individuals. Life coaches focus on establishing trust and building relationships with their clients, many of whom have little to no support within traditional institutions.

Life coaches and their clients often come from similar backgrounds, and through providing support and sharing their own life experiences, life coaches are able to build transformative relationships with high-risk individuals. Life coach Javier Jimenez has been working with Oakland Unite for five years, but some time ago, it was Javier who needed to turn his life around. “Somebody saw something in me I didn’t see in myself,” said Javier. “I see something in them that they might not see themselves too.”

Success looks different for different people, pointed out life coach Edward Moore, who has been working with Oakland Unite for three years. One particularly violent client of Edward’s cited a number of personal accomplishments, including getting off probation, holding a job for more than six months, and spending more time with his child.

3. Pastor Michael McBride and Reverend Ben McBride

Brothers Pastor Michael McBride, director of Urban Strategies at Faith in Action, and Reverend Ben McBride, co-director of Pico California, are leaders in Oakland’s faith community and a formidable force for peace in a city long racked by violence. Reverend Ben emphasized the important role that faith communities played in cutting Oakland’s gun violence in half in six years.

He also spoke about the importance of making sure the Ceasefire coalition is multiracial, multi-faith, and spread out across various expressions of power in order to hold people responsible for implementing the strategy.

Reverend Ben helped lead the first procedural justice training for the Oakland Police Department, which directly addressed the strained relationship between law enforcement and the city and encouraged police officers to interact with the community more thoughtfully. “Both parties need to be humanized in practical, consistent ways,” said Reverend Ben.

He describes a moment in which he realized that many officers are also operating within a system where they didn’t feel seen, heard, or humanized. At procedural justice trainings, Reverend Ben started telling the officers gathered, “I don’t know what it feels like to walk in your shoes.” He didn’t know what it felt like, he told the officers, to put his life on the line day after or day, or to leave for work not knowing if you’re coming home.

“I only know what it means to walk in these shoes,” he said, holding up a pair of black size-14 Air Force One tennis shoes, “and my hope is that if I talk about these shoes enough, we can get these shoes and your shoes together on the same journey.”

4. Reverend Damita Davis-Howard

Reverend Damita, an assistant pastor at First Mt. Sinai in Oakland, has lost several family members to gun violence: a younger brother, a god-brother, a god-son, two second cousins, and a young niece, who was killed by a stray bullet fired from two blocks away.

In 2011, Reverend Damita was a leader at Oakland Community Organizations attending regular clergy meetings. Hearing Pastor Michael McBride speak helped change her perspective on what was required to tackle the gun violence epidemic—as did weekly night walks.

At one of these walks, Reverend Damita said, faith leaders and community activists ran into young men hanging out on the corner who said, “Sure this great, but you won’t be here next week or next month.” The next month, the group returned to the same corner. One of the men was so surprised to see them again, he shared photos of the night walk on social media.

She commends the young men who are seeking different paths, paths not characterized by bullet casings and dead ends but by hope and opportunity. “The reason we have fewer victims of gun violence is because fewer people are shooting,” said Reverend Damita. “Which means someone is making a different choice.”

5. Captain Ersie Joyner

Ersie Joyner grew up in East Oakland. One day while in college, he was caught off guard by a professor who told him he thought he would make a great police officer. Ersie rattled off “a litany of things” that had happened to him and his family and friends at the hands of the police. “I thought I’d dropped the mic,” he said.

The professor responded without hesitation, “That’s exactly why you should be the police.”

When Ersie joined the Oakland Police Department in 1991, he started out making undercover drug busts. Today, he heads Oakland’s Ceasefire Section, responsible for targeted law enforcement actions addressing serious violence within the community.

“It’s just about treating people as our customers,” Ersie said of his efforts to strengthen the relationship between the police and the community. Throughout the country, it’s been an “us versus them mentality and culture,” he said. Changing this, he said, is like turning around a cruise ship

Like Reverend Damita, Ersie stressed the importance of giving credit where credit is due. Most people in the community don’t know about the year after year success with violence, Ersie said. “We need to find a way, not as a police department, but as a city, to lift them up and to talk about those wins, so that it encourages other people to win. And then we need to find a way to message, because to be honest, it’s more courageous to not pick up a gun.”

Learn More

- Blog: How Oakland Cut Homicides In Half

- Background: Urban Gun Violence

- Factsheet: Proven Solutions to Urban Gun Violence