His Words Kept Me Hostage, But Now I’m Speaking Out

Note: Since this post was published, Christy has filed a lawsuit seeking more information about how Wyland’s father was able to purchase the firearm he used despite the restraining order against him.

Content warning: This post contains a description of domestic violence and suicide.

I wasn’t sure whether I should write this blog post.

It’s October, which means it’s Domestic Violence Awareness Month. I was connected by a friend to Giffords, a survivor-led national gun violence prevention organization, who suggested I write a post about my experiences. I agreed, but I had my reservations.

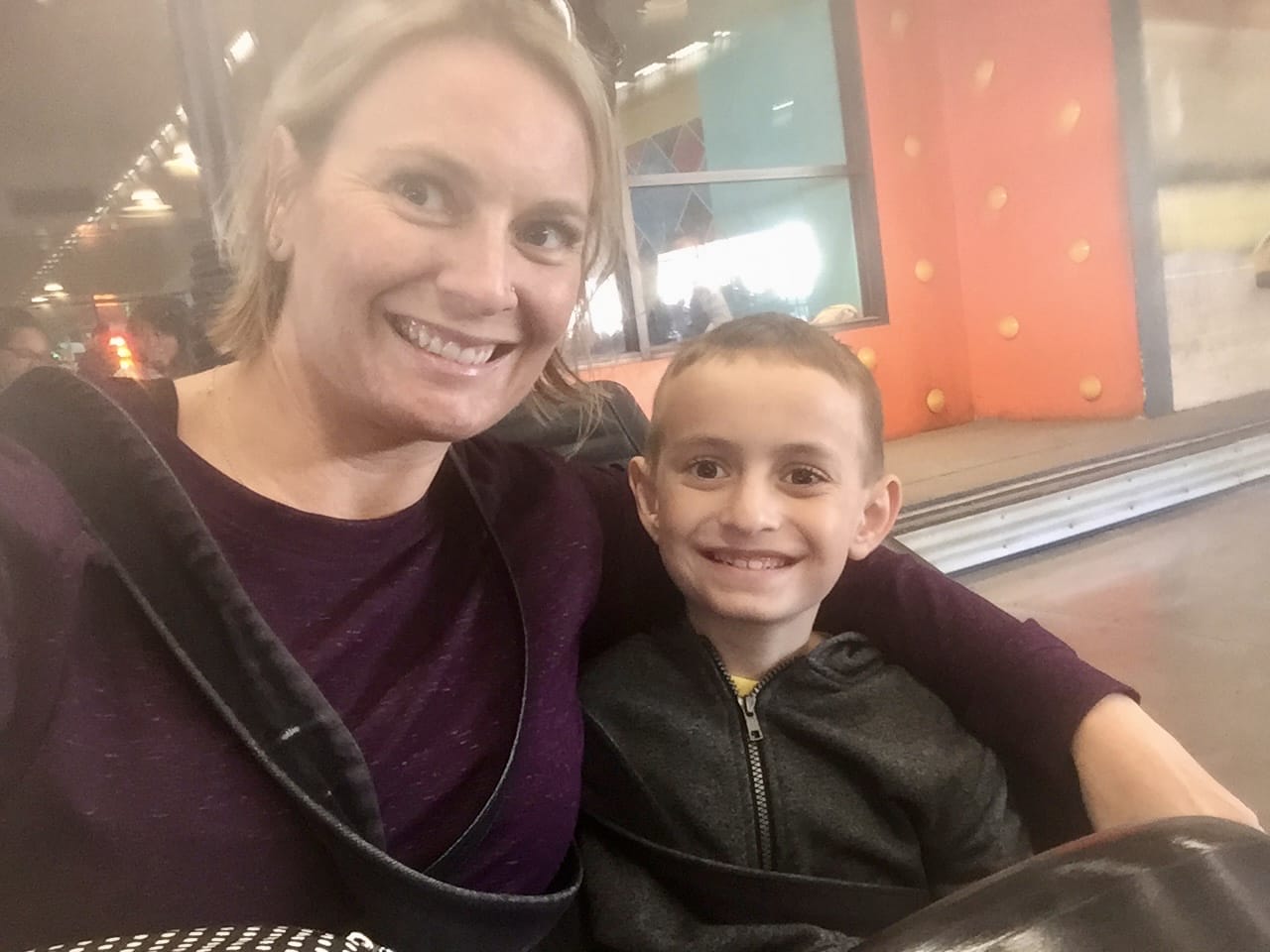

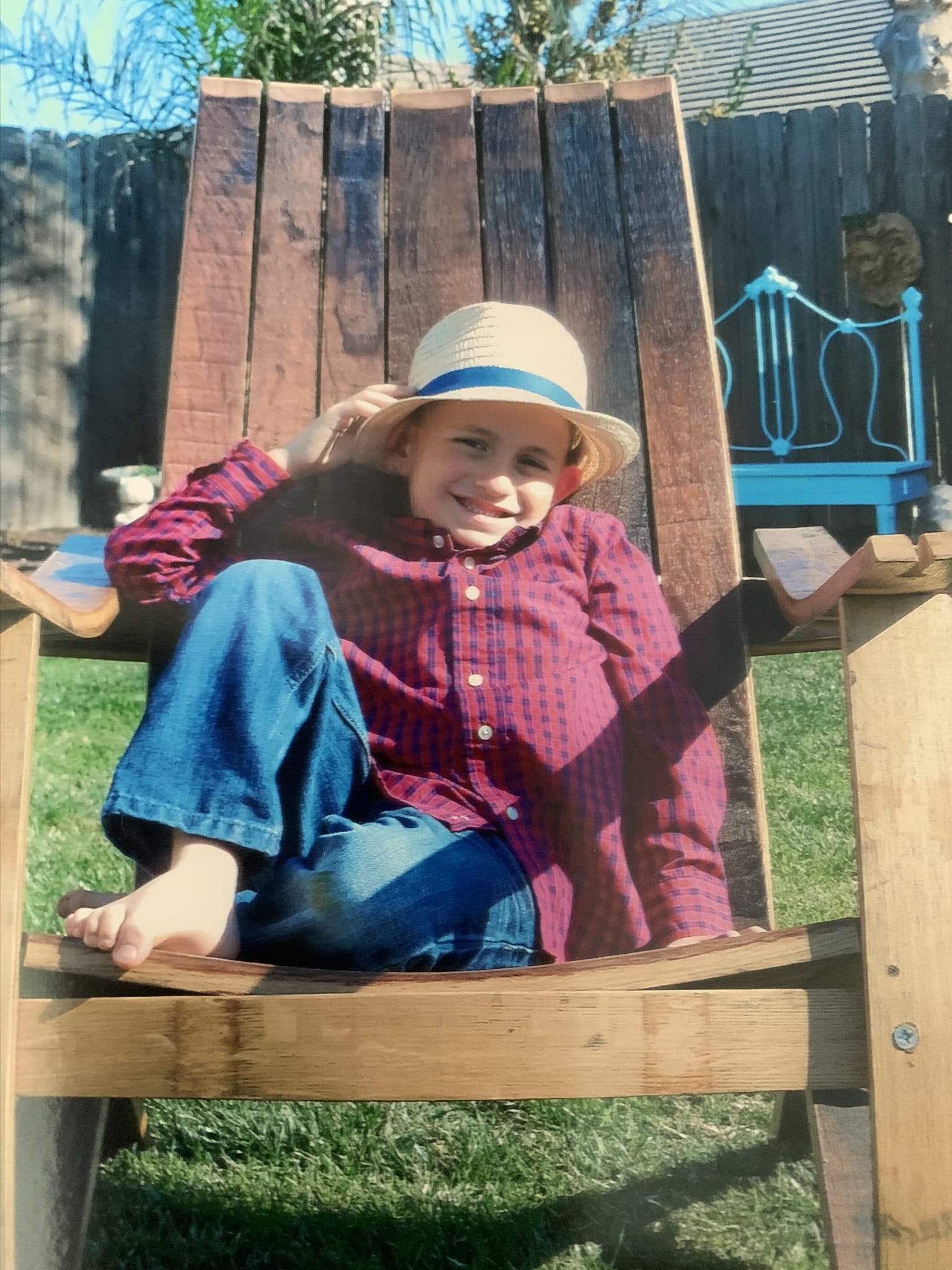

When I spoke to my therapist, Kelly, a few days later, she helped me understand my hesitation. Even now, more than two years after my ex-husband shot and killed our 10-year-old son and then himself, I struggle to identify as a domestic violence victim.

Domestic Violence

The combination of intimate partner violence and access to guns is an especially deadly mix.

My ex-husband was diagnosed with depression and bipolar disorder. My son, Wyland, and I experienced emotional manipulation and verbal abuse at his hands, and I was held hostage by the fear that he would hurt me, my son, or even himself. I worried my ex-husband would take his own life, causing our son to suffer emotionally for the rest of his life.

But I wasn’t physically abused. Maybe if I had a black eye, others would have noticed—or I would have. But mental abuse doesn’t work that way, at least not for me. While there were no visual manifestations of violence, his emotional abuse created small bruises on my psyche. After eight years of marriage, I became a shell of a person. I was worried I might be caught in an outburst or manic episode, and that I wouldn’t be able to decode his messages and actions. If he took too long to respond to a text message, I worried about Wyland’s safety.

My ex-husband and I divorced in 2016. I thought some space would help both me and Wyland, but the manipulation continued. I felt like there wasn’t anything I could do. If I didn’t allow my son to see his father, both of them would get upset. I didn’t put this together until after the shooting, but I realize now that Wyland began to take on the responsibility of worrying for my ex-husband’s health and safety. He was too young to understand that he couldn’t keep his father safe.

Since Wyland’s tragic death, I’ve become even more aware of the signs of abuse. I’m aware of the pain and exhaustion, of the word “filicide”—which means the killing of one’s son or daughter—and of the need to warn others of what to look out for. I’m aware that I was a victim of domestic violence—and that was a huge awakening for me. There are probably others in similar situations who have no idea they’re victims as well.

Though I didn’t witness my son’s death, I suffer from PTSD and secondary trauma. I replay the event in my head often, trying to put together the pieces of the real-life nightmare. I will never forget the crime scene, blocked off with barricade tape. In the months after, the sight of caution tape on TV would make me cry. Having to say goodbye to my son in a hospital bed in the emergency room, hours after he passed, was the worst moment of my life.

I tried several treatment techniques with my therapist to overcome these hurdles. The trauma has taken a toll on my brain—sometimes, I lose my train of thought and pause in the middle of a sentence. It’s frustrating, and embarrassing.

I think many trauma victims don’t share their stories because they don’t know what to say, or are afraid of saying the wrong thing. Victims and survivors often feel alienated by our responses to trauma, like forgetting thoughts, having trouble speaking, or crying and shaking. But we must support survivors—and this includes listening to them when they have a story to tell, even if it comes out in broken segments.

Each time I question whether or not to speak, I remind myself that my voice is powerful. If I chose to avoid embarrassment or fear by not speaking at all, how would I share my story? How would people learn that this can happen?

It’s too easy for those who pose a threat to themselves or others to access guns, and it’s especially dangerous when this happens around children. Each time a survivor shares their story, we take another step forward, towards progress.

You are not alone. If you or a loved one is experiencing domestic violence, please call the National Domestic Violence Hotline at 1-800-799-7233 or visit thehotline.org. If you or a loved one are contemplating suicide, please call the free and confidential national Suicide & Crisis Lifeline by dialing 988 or access help through their website at 988lifeline.org.

SPOTLIGHT

REDUCING RISK

Explore the options and strategies available for addressing specific types of gun violence and reducing the risk of a dangerous situation ending in tragedy.

Read More