ATF: Captured by the Gun Lobby

Introduction

In September 2021, the White House announced that it was formally withdrawing its nominee, David Chipman, for the position of director of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms & Explosives (ATF). ATF is the primary federal agency responsible for implementing and enforcing our national gun laws, and prior to his nomination, Chipman was a prominent advocate for stronger gun safety laws and a senior advisor at Giffords. When President Biden withdrew David Chipman’s nomination for ATF director, the trade association for the gun industry, the National Shooting Sports Foundation (NSSF) quickly claimed victory, asserting that it “led the opposition.”

ATF: Captured by the Gun Lobby Executive Summary

In April 2022, President Biden nominated former US Attorney Steve Dettelbach for the same position. Once again, the NSSF opposed the president’s choice to lead ATF.

This report explains the reason for NSSF’s desperate opposition to both nominations, an opposition that, in reality, had little to do with the nominees themselves. For years, the gun industry, led by NSSF, has developed an exceptionally cozy relationship with ATF, a relationship that has enabled the industry to exert tremendous influence over the agency. This influence benefits the industry, but has undermined ATF’s ability to do its job: to protect public safety from gun violence by enforcing the laws regarding firearms and firearm sales.

The influence of the gun industry over ATF manifests itself in a number of ways, all of which threaten public safety and demonstrate that ATF has been “captured” by the industry:

- First, too frequently ATF has deferred to the industry regarding important policy decisions, causing ATF to actively advocate on behalf of the industry within the Department of Justice (DOJ) and unquestioningly accepting the opinion of the industry regarding the classification of particular weapons.

- ATF has also taken an extremely lenient approach towards irresponsible gun stores, often enabling them to stay open despite clear violations of the law.

- The gun industry has successfully mobilized against a number of presidential nominees for ATF director, leaving the agency without long-term, dedicated leadership willing to stand up to the industry.

- A lack of transparency within ATF has also benefited the industry and deprived policymakers and the public of information about the gun industry and ATF’s activities in regulating (or not regulating) them.

- Finally, the industry, and in particular NSSF, has used its partnerships with ATF to avoid any sort of bad press, instead cultivating a positive image for gun businesses and building its brand name.

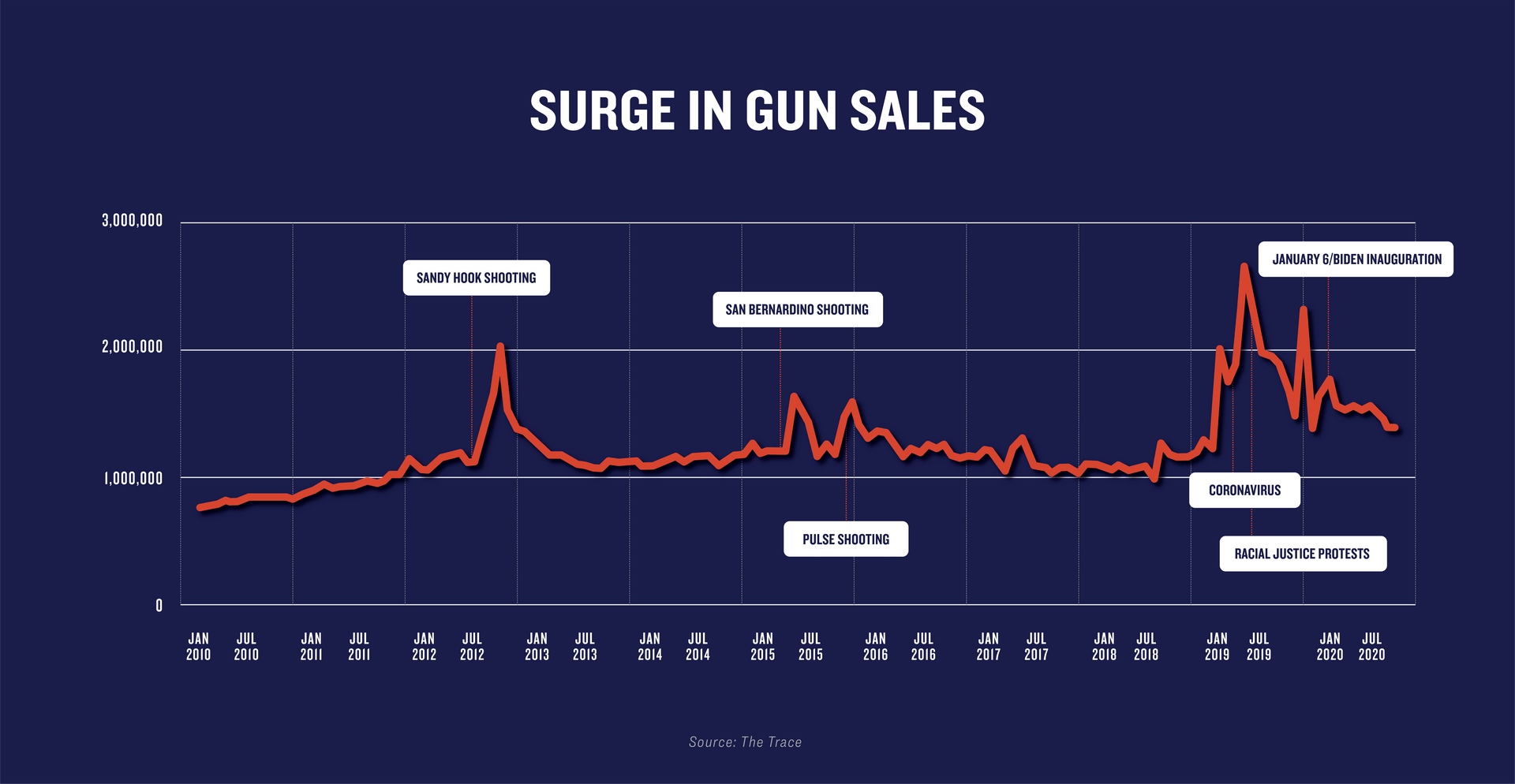

Meanwhile, gun sales have increased dramatically over the past several years1 and gun violence is soaring, with the CDC reporting a record number of 45,000 gun deaths in 2020.2 Much of the blame for this state of affairs lies with Congress, which has consistently underfunded ATF over the course of decades3 and has enacted restrictive legal provisions that weaken ATF’s legal authority and mission capacity.4

The Senate bears particular responsibility for the situation. Despite several nominations from recent presidents, it has failed to confirm a director for the agency until this year. The agency has had nine different directors since 2006—all but two of whom served on a temporary basis as “acting director.” The absence of a Senate-confirmed director has meant that the agency has lacked the strong leadership necessary to stand up to the firearms industry.

Nevertheless, some of the blame also falls within the DOJ, which houses ATF, and ATF itself. Strong, independent leadership both from inside ATF and from DOJ could take steps to rehabilitate the agency, removing it from the sway of NSSF and strengthening its ability to prevent gun violence. Even if Congress fails to act, the culture and practices of ATF should be changed so the agency can free itself from the influence of the gun industry and provide stronger oversight over firearms businesses, so that only those who operate responsibly are able to sell firearms to the public and those who do not are held accountable.

What Is a Captured Agency?

In failing to effectively regulate the gun industry and repeatedly bowing to the influence of firearms businesses in general, and NSSF specifically, ATF is manifesting many of the symptoms of a “captured agency.” The concept of “agency capture” refers to the tendency of any government agency responsible for regulating an industry to become “captured,” or heavily influenced, by the main players in that industry. When a government agency becomes captured by the industry it is supposed to regulate, it is unable to accomplish the goals Congress intended for it.

A captured agency defers to a particular group of stakeholders, disregarding the larger goal of governmental regulation: to protect the public and accomplish what’s in the best interests of the country by implementing laws. When a government agency has been captured by an industry that it is meant to regulate, the agency makes decisions based on what is best for that industry’s profits, rather than what serves the public or the country as a whole.

According to researchers, regulatory capture occurs because a regulated industry is likely to invest significantly in influencing the government agency that regulates it, while members of the public may not have the resources or motivation to do so.5 An agency can also become captured by an industry if it must rely on the industry for technical expertise or if the industry presents employees of the agency with the possibility of lucrative future employment. If the agency must draw from the same pool of experts in the field as the industry, often those experts bring with them the culture and beliefs of the industry, and a “revolving door” is created, whereby the same individuals move from employment within the industry to employment within the agency, and back again. Research has also shown that small agencies have a greater tendency than larger agencies to become captured by the industry they regulate, since they lack the strength and resources to withstand the influence of the industry.

One classic example showing the potentially disastrous results of agency capture involved the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in 2010. The Minerals Management Service, which regulated offshore oil drilling, had waived permit requirements and environmental assessments for BP and other oil companies that wished to drill in the Gulf of Mexico. All too predictably, an explosion on an oil rig operated by BP leaked millions of barrels of oil into the Gulf and caused one of the worst environmental disasters in our nation’s history. Scientists have estimated that over one million birds died because of the spill, and one researcher estimated the overall cost of the spill to be $144.89 billion.6

Accusations of agency capture have also been made against many other regulatory agencies in the US, including, most recently, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for its role in enabling the opioid epidemic,7 and the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) for certifying the Boeing airplane model involved in the 2018 and 2019 crashes of Lion Air Flight 610 and Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302, in which a total of 346 people died.8

Researchers say regulatory capture can be prevented by protecting government agencies from influence by the industries they regulate and ensuring these agencies act with transparency. Vigorous public scrutiny and strong leadership and oversight can also help protect an agency from regulatory capture and ensure that the agency maintains its focus on enforcing the law and serving the public interest.

TAKE ACTION

The gun safety movement is on the march: Americans from different background are united in standing up for safer schools and communities. Join us to make your voice heard and power our next wave of victories.

GET INVOLVED

ATF’s Mission

ATF is the primary agency charged with enforcing our nation’s gun laws. Unfortunately, the history of the agency and the laws it is charged with enforcing have led to a situation where ATF is especially vulnerable to agency capture. This vulnerability affects ATF in all its roles involving firearms.

Regulating Gun Dealers

ATF shares criminal law enforcement responsibility with other federal agencies, such as the FBI, and is also responsible for regulating alcohol, tobacco, and explosives. However, from early on, ATF has been assigned the specific role of not only investigating and prosecuting violations of criminal laws involving firearms, but also regulating the businesses that manufacture, import, and sell firearms. ATF is the only federal agency charged with the responsibility of providing oversight for the gun industry and ensuring that gun businesses comply with applicable laws and regulations.9 Over the years, fulfilling these crucial functions has become more difficult as Congress has failed to provide the agency with the legal and financial support it needs to keep pace with the fast-growing gun industry.

Giffords Calls on Senate to Confirm Dettelbach

May 25, 2022

Despite the importance of its mission, ATF operates with a meager legal framework with respect to guns. Under the Gun Control Act of 1968, gun manufacturers, importers, and dealers are required to obtain a license from ATF. Only these federal firearm licensees (FFLs) are allowed to sell and buy guns across state lines.10 This means that FFLs generally have access to large numbers of guns that unlicensed individuals do not. ATF is supposed to ensure that FFLs fulfill certain limited requirements, such as maintaining records of inventory and sales and reporting lost or stolen guns. ATF also has the authority to revoke the license of a business that willfully fails to comply with these laws.11

The Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act, enacted in 1993, added the most crucial feature of this system of regulation: a requirement that these businesses conduct background checks on gun purchasers. This background check requirement is fundamental to preventing guns from falling into the wrong hands by ensuring that people who have been convicted of felonies or domestic violence, or are otherwise not eligible to possess firearms, are not able to purchase them.12 This requirement only works if FFLs comply with the law by conducting background checks on every gun purchaser. ATF is responsible for ensuring that FFLs perform this vital task.

When the gun industry fails to comply with these laws, guns can end up being trafficked into the illegal market and used in crimes. This can also happen when irresponsible FFLs fail to secure their guns against theft. According to ATF, FFLs reported 13,173 firearms lost or stolen from their inventories in the year 2020 alone.13 These firearms pose a serious risk to public safety because they have been diverted from legal commerce, with no record of the owner and no background check conducted. FFLs may also be negligent by allowing straw purchases—illegal purchases by individuals other than the actual buyers, which enable the actual buyers to avoid the background check or record-keeping requirements.

In addition, over the last two decades, the gun lobby has successfully advocated for a number of legal provisions that interfere with ATF’s authority over FFLs. The Firearms Owner Protection Act (FOPA), for example, which was enacted in 1986, limited ATF’s ability to conduct FFL inspections.14 Due to FOPA, ATF may conduct only one inspection of an FFL per year, unless it relates to a specific criminal investigation.15 FOPA also prohibits ATF or any federal agency from creating a centralized registry of gun sale records.16

Regulating Unusually Dangerous Firearms

In addition to these laws that apply to all firearms, ATF is also charged with a crucial role with regards to unusually dangerous firearms, including machine guns, short-barreled rifles, sawed-off shotguns, and silencers. The National Firearms Act (NFA) established a system of taxation and regulation for these weapons in 1934. Because of the NFA, any FFL or other person making, manufacturing, importing, or selling even a single one of these firearms must apply for approval from ATF. After ATF processes these applications, each firearm is registered to the possessor.17 Because of this framework, these guns are rarely used in crimes.18

The NFA does not, however, apply to the vast majority of firearms in this country, and, as discussed below, it is not always clear whether a particular dangerous weapon is subject to the NFA. Furthermore, due to the influence of the gun lobby over Congress, this legal framework has been updated very rarely. As a result, the industry has been able to develop many new forms of weaponry and argue that they are not addressed by the federal laws.

As described in more detail below, ATF has not been able to push back against these arguments, enabling the industry to continue circumventing the spirit, if not the letter, of the law, and preventing ATF from being able to effectively address these modern styles of firearms and the dangers they present to the public.

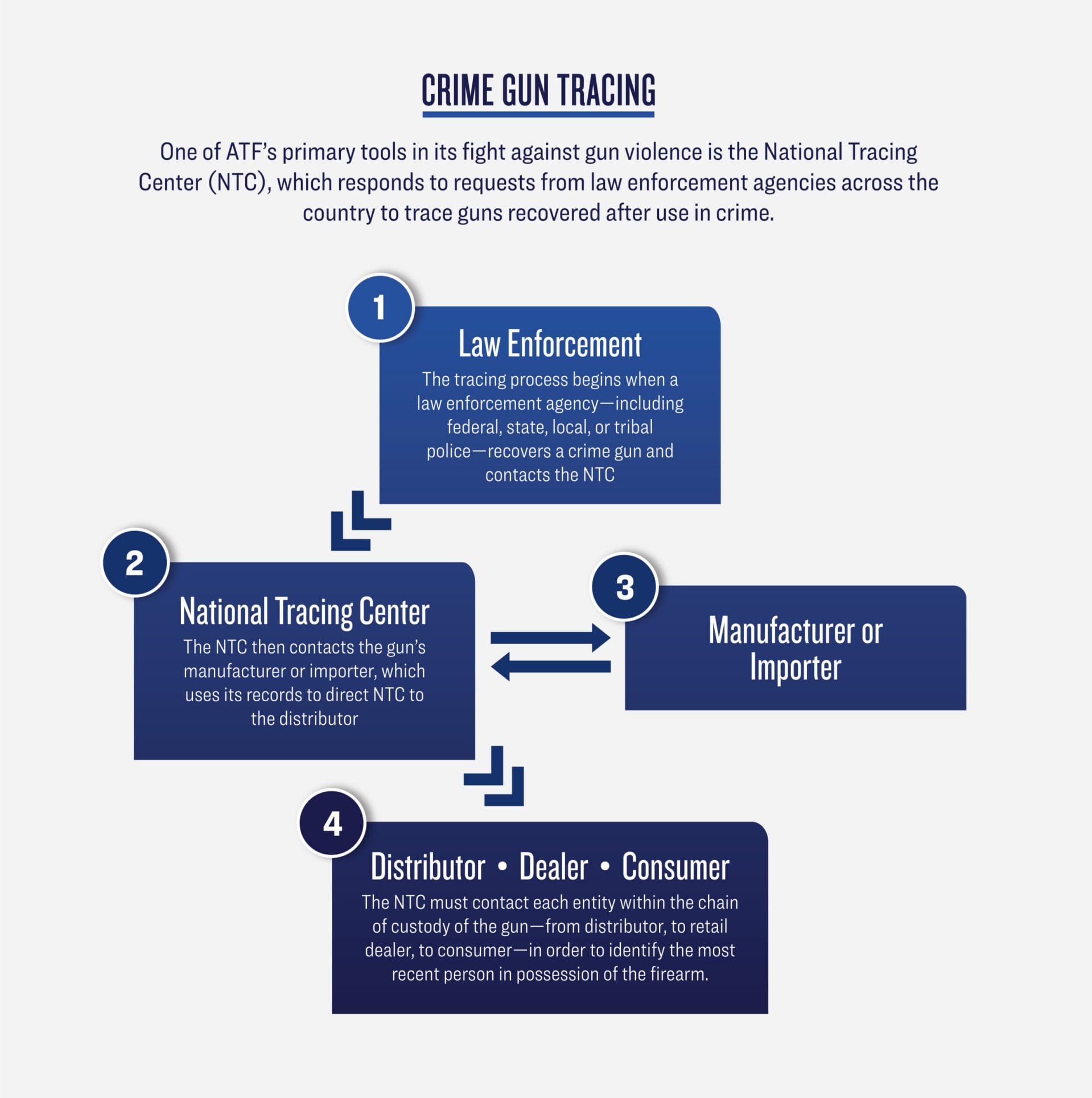

Tracing Firearms

One of ATF’s primary tools in its fight against gun violence is the National Tracing Center (NTC), which responds to requests from law enforcement agencies across the country to trace guns recovered after use in crime. The tracing process begins when a law enforcement agency—including federal, state, local, or tribal police—recovers a crime gun and contacts the NTC. The NTC then contacts the gun’s manufacturer or importer, which uses its records to direct NTC to the distributor. The NTC must contact each entity within the chain of custody of the gun—from distributor, to retail dealer, to consumer—in order to identify the most recent person in possession of the firearm.

Federal law requires an FFL to provide information from its records no later than 24 hours after receipt of a request by ATF for use in a criminal investigation,19 but explicitly prohibits ATF or any federal agency from establishing a centralized system for the registration of firearms.20

Consequently, ATF (and by extension law enforcement across the country) is dependent on the gun industry’s records of its own gun sales for the information these agencies need to track down those who have committed gun crimes or engaged in gun trafficking. In fiscal year 2020, the NTC received more than 490,000 trace requests from law enforcement agencies across the country, a 43.1% increase over the past 10 years.21 Yet, the NTC’s funding has not kept pace with this demand.

Congress has also limited ATF’s authority through a number of riders, known as the Tiahrt Amendments, in appropriations bills that specifically restrict how ATF uses its funding:

- One of these riders limits the extent to which the data that ATF gathers by tracing firearms can be released to the public.22

- Another limits the extent to which the records of out-of-business dealers, which are sent to ATF when FFLs shut down, can be put into a searchable database.23

- A third one prohibits ATF from requiring FFLs to conduct physical inventories of their firearms.24

- A fourth rider requires the destruction of the FBI’s background check records within 24 hours after a sale is approved.25

All together, these riders make it harder for ATF to identify irresponsible or corrupt FFLs that endanger public safety while also limiting the information the public can gather about FFLs. They also make ATF dependent on FFLs for information necessary to prevent gun trafficking and ensure that guns remain in the hands of those eligible to possess them. For those within ATF who favor the gun industry over public safety, these provisions provide a convenient excuse for failing to accomplish the central goal of ATF: to prevent guns from falling into the wrong hands. Instead, they are enabling gun violence.

ATF and the Gun Industry

The gun industry has experienced dramatic growth over the last two decades, both in terms of guns manufactured and guns sold. According to ATF, the number of firearms that were domestically manufactured, exported by US manufacturers, and imported into the US increased by 187%, 240%, and 350%, respectively, between 2000 and 2020, while the US population increased by only 18%.26 Most notably, the number of firearms manufactured in the US, which had fluctuated between two and five million annually through 2008, ballooned during the Obama presidency to average almost 8.5 million each year between 2009 and 2019, and reached an all-time high in 2016, with 11,497,441 firearms manufactured in that year alone.27

The best estimates indicate that the number of guns sold over the last decade has also doubled, with an additional spike in 2020, so that the number of guns sold in 2020 was 275% of the number of guns sold in 2010.28

Likewise, the number of applications ATF processed under the NFA—including applications to make, manufacture, or transfer machine guns, silencers, and other NFA weapons—remained under 350,000 each year until 2006. Since then, that number has grown dramatically, with ATF processing almost two million NFA applications each year from 2016 to 2020 on average.29

According to the Center for American Progress, this growth involves gun production largely concentrated among a few large manufacturers. Three manufacturers produced more than 58% of pistols from 2008 to 2018: Smith & Wesson Corp., Sturm, Ruger & Co. Inc., and SIG SAUER Inc, and three manufacturers also produced more than 45% of rifles from 2008 to 2018: Remington Arms, Sturm, Ruger & Co. Inc., and Smith & Wesson.30 More recent ATF data confirms this idea.31

The growth of the gun industry is concerning in part because of the misleading messages that the industry has spread in order to fuel this growth. For decades, marketing by the gun industry has misled the American public about the impact of having a gun in the home. Social science research has repeatedly shown that having a gun in the home increases the risk of firearm homicide and suicide. Yet the gun industry has convinced much of the American public that they need guns to protect themselves and their families. The gun industry has specifically targeted women with this message.32 The industry has also been increasingly selling military-style weapons to civilians, using the fact that these weapons are intended for combat as a selling point and attempting to rebrand assault weapons as “modern sporting rifles.”33

In more recent years, some gun industry advertisements have taken an even more aggressive tone, exploiting people’s fears related to COVID-1934 and anti-Asian hate crimes,35 as well as Antifa.36 The gun industry’s ability to reach people with these misleading and dangerous messages has only increased with the rise of social media.37

It is unclear what proportion of gun industry members are comfortable with these advertising tactics, which are led primarily by manufacturers. In the past, individual members of the industry have occasionally voiced concerns,38 but, because of their size, large manufacturers have an outsized voice in the industry.

While the industry has grown rapidly, ATF has not experienced proportional growth because Congress has not adequately funded it. Its budget remained essentially unchanged between 2010 and 2020, increasing by only six percent when adjusted for inflation.39ATF’s staff has also not significantly increased for several decades. According to ATF’s most recent report, since 1973, the number of employees at ATF has increased only 41%.40 In contrast, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) experienced a 254% increase in the number of employees and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) experienced a 75% increase in the number of employees during the same time period.41

The relative stagnation of ATF’s size in conjunction with growth in the gun industry has created a serious power imbalance and made ATF vulnerable to influence and coercion as its mission to enforce laws has become exponentially more difficult.

Innovations within the gun industry are now presenting ATF with new challenges, such as the rise of untraceable “ghost guns” and auto sears. Ghost guns (which ATF labels “privately made firearms” or “PMFs”) are homemade, “do-it-yourself” firearms assembled from parts. They evade regulations such as background checks and serial numbers and present a rapidly increasing threat to public safety. Nearly 24,000 ghost guns were recovered at crime scenes between 2016 and 2020,42 and the number of ghost guns found in the possession of convicted felons and other so-called prohibited persons doubled from 2018 to 2019.43 According to ATF, “the number of suspected PMFs recovered by law enforcement and subsequently traced by ATF” increased by 1,000% between 2016 and 2021.44 In April 2022, ATF finalized a new rule that limits the unfinished firearm parts that avoid regulation as firearms. This rule will not go into effect until August, however, and the rule by no means prevents the industry from using other technological innovations to evade the law.

Another dangerous technology that ATF has struggled to effectively regulate is the auto sear, a device that can be attached to a firearm enabling it to fire automatically.45 These devices are illegal, but are often smuggled into the country or constructed through 3D printing.

This combination of these new threats and the relative sizes of ATF and the industry has led to an emphasis within ATF on cooperation and alignment with the gun industry and a reluctance to take actions that may threaten gun industry profits, as ATF is largely reliant on the industry to police itself. According to its most recent budget submission, “the ATF works with its regulated industries to prevent violence and safeguard the public while endeavoring to minimize regulatory constraints that impact lawful commerce in firearms and explosives.”46

Notably, while ATF’s website has clearly marked “Tools & Services for the Gun Industry” alongside “Tools & Services for Law Enforcement,” there is no defined area for those members of the public interested in helping to prevent gun violence.47

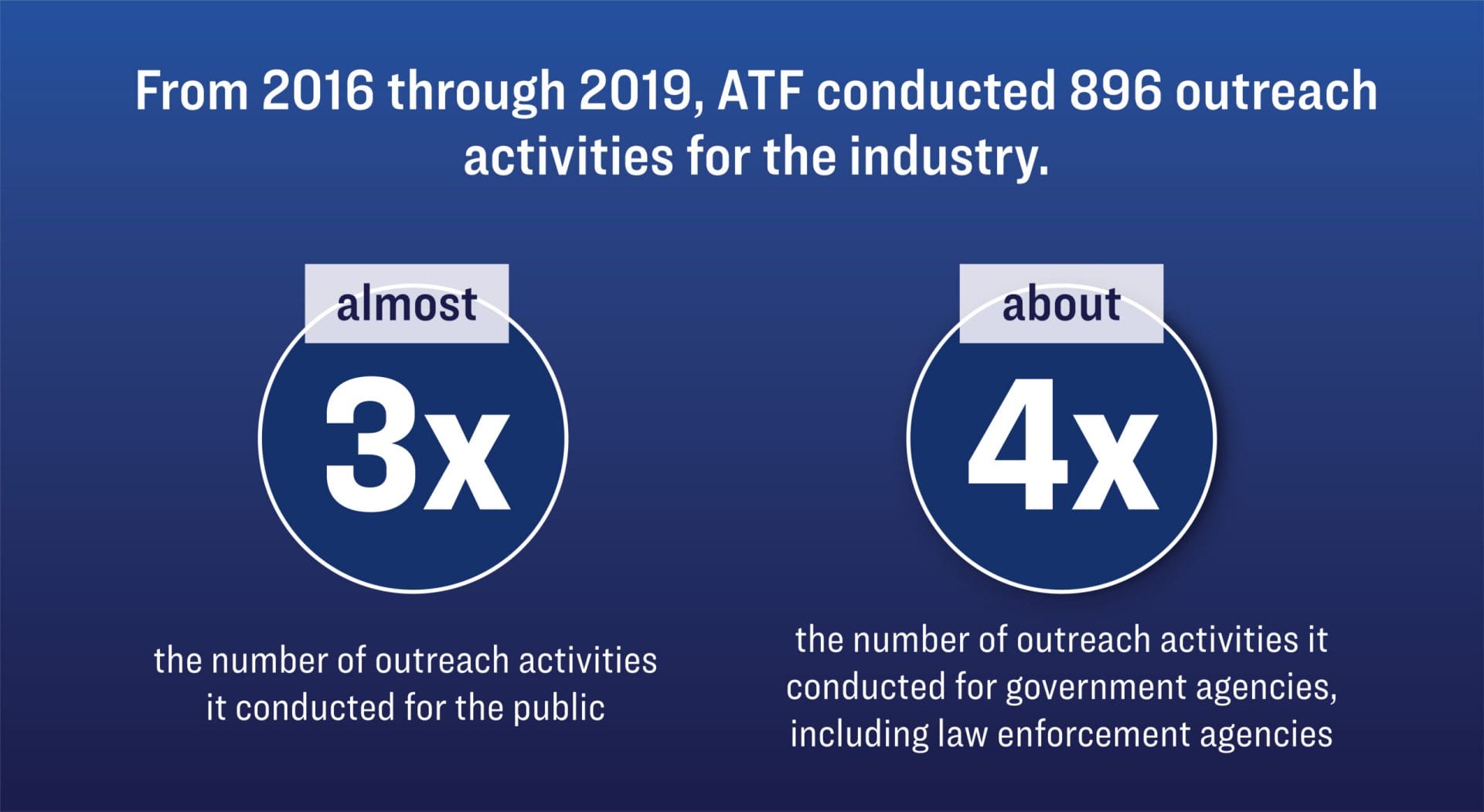

ATF’s most recent report also highlights outreach to the industry. According to that report, from 2016 through 2019, ATF conducted 896 outreach activities for the industry, almost three times the number of outreach activities it conducted for the public, and about four times the number of outreach activities it conducted for government agencies, including law enforcement agencies.48

NSSF and ATF

The explosive growth of the industry over the last decade has coincided with the consolidation of power in the National Shooting Sports Foundation (NSSF), an organization dedicated to furthering the industry’s special interests with increasingly extremist views. In fact, in recent years, NSSF has largely replaced the NRA as the voice of the gun lobby while simultaneously branding itself as a trade association dedicated to firearms safety and cultivating a close relationship with ATF.

NSSF, which is headquartered in Newtown, Connecticut, was founded in 1961. Its membership is now made up of 8,000 gun retailers, manufacturers, importers, shooting ranges, and sportsmen’s associations. Although NSSF portrays itself as representative of smaller mom-and-pop gun stores, larger manufacturers of firearms contribute an over-large portion of its budget,49 and manufacturers constitute two-thirds of the members of NSSF’s Board of Governors who are not employees.50

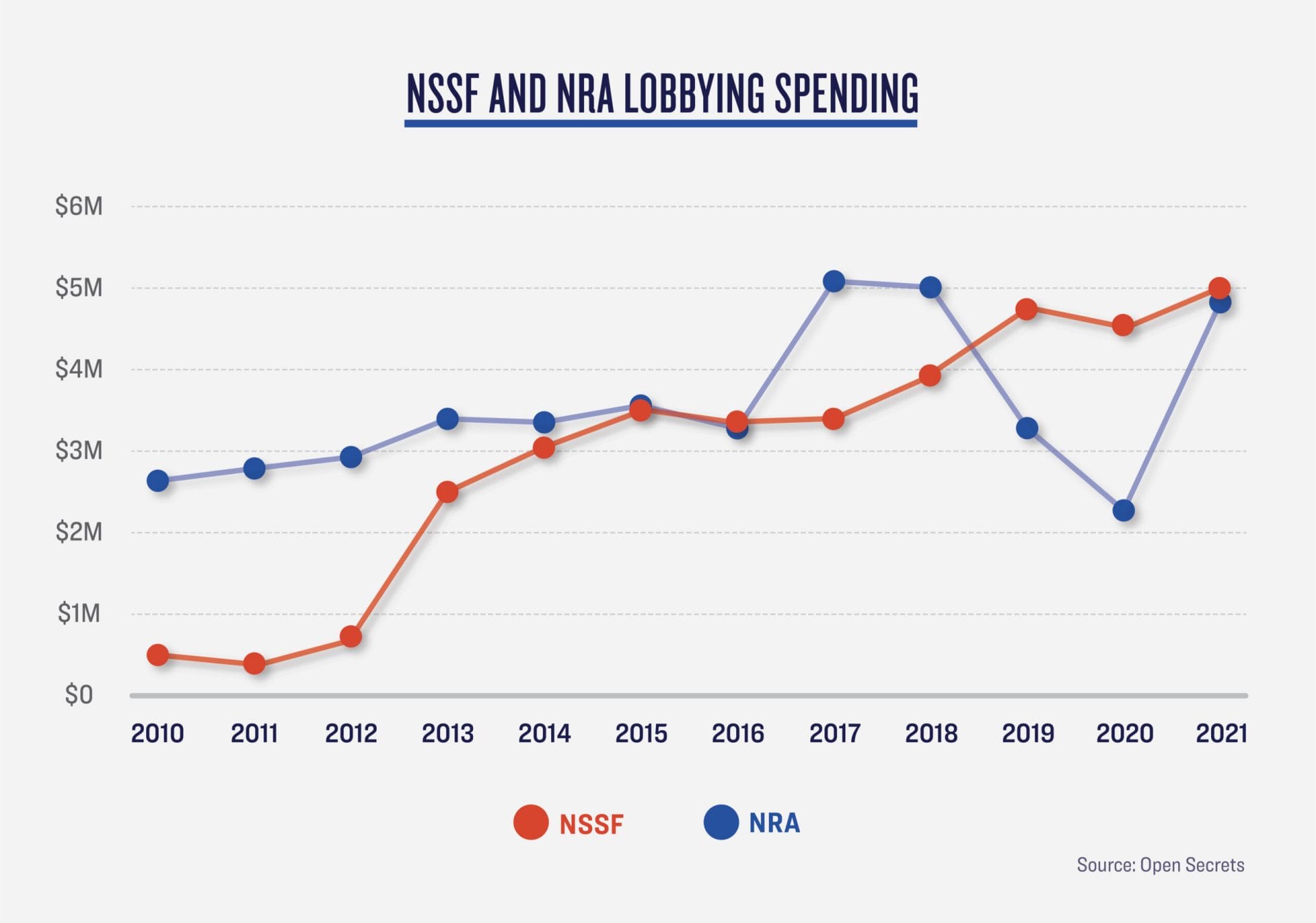

NSSF also heavily touts itself as promoting “firearms safety,” but in reality, from April 2014–March 2019, NSSF has never spent more than 5.8% of its revenue on “Safety & Education” programs.51 Instead, NSSF has dramatically increased its legislative lobbying efforts in recent years and now regularly spends more on lobbying than the NRA. Before 2013, the organization had never spent more than $400,000 in any one year on lobbying. Since 2013, NSSF has spent between $2.5 million and $4.8 million on lobbying annually.52 In 2020, it spent more than twice as much as the NRA on lobbying.53

NSSF funds these activities largely through its annual Shooting, Hunting, Outdoor Trade Show (the SHOT Show), the largest firearms trade show in the country, which is closed to the public. In addition to funding NSSF itself, the event also provides an opportunity for firearm and ammunition manufacturers to show off the newest weaponry so that representatives from gun dealers can choose how to stock their shelves. At the 44th annual SHOT Show, held in January 2022, more than 2,400 companies displayed products and services in booths covering more than 800,000 net square feet.54 This SHOT show also featured 27 manufacturers and distributors of ghost guns—untraceable guns made from kits or 3D printers that don’t require background checks.55

From 2008 through 2019, NSSF derived over 75% of its revenue from the SHOT Show.56 When the SHOT Show was canceled in 2021 due to COVID-19, gun manufacturers showed how thoroughly committed they are to keeping NSSF running: they made up for the NSSF’s lost revenue by contributing to the organization directly.57

The event serves other purposes beyond a simple trade show and revenue generator: it also provides an opportunity for members to share viewpoints and align themselves with the overall thinking of the organization. More importantly, it provides an opportunity for the industry to interact with law enforcement agencies and officers, whom it draws to the show. The SHOT Show features a Law Enforcement Education Program (LEEP)58 in which members of industry have the opportunity to “educate” law enforcement about protection measures and “practical execution strategies.”

ATF in particular has a strong presence at the show, staffing a booth with agents to answer compliance questions for industry members. On average, about 55 ATF staff members have attended the three-day event each year since 2015, according to an agency tally of attendees provided by an administration official.59

A video-taped interview between NSSF Senior Vice President and General Counsel Larry Keane and ATF Acting Director Marvin Richardson during the 2022 Shot Show illustrates the cozy relationships that are nurtured at these events.60 Throughout the conversation, Richardson was careful to be only complimentary to the industry and NSSF. Meanwhile, Keane explicitly emphasized the strong relationship between NSSF and ATF, crediting Richardson for his “leadership” in this relationship, which he says “couldn’t be any stronger.”

Richardson then followed Keane’s prompting to discuss several partnerships between NSSF and ATF, starting with “Don’t Lie for the Other Guy,” a campaign against straw purchasers who buy guns on behalf of others, illegally bypassing the background check requirement. As Keane put it, the person at the store counter is the first line of defense against illegal diversions of firearms, and dealers are the number one source of info for trafficking investigations.61 Richardson nodded as Keane emphasized ATF’s dependence on the industry.

Keane also prompted Richardson to talk about “Operation Secure Store,” another partnership between ATF and NSSF. This partnership is focused on exchanging information to eliminate burglaries and thefts from gun stores, a serious problem that could be reduced by better security measures within gun stores like burglar alarms, security cameras, and better physical barriers. Instead, Richardson openly emphasized ATF’s lack of authority to require gun stores to use security measures, and was careful to avoid placing any blame on gun stores, instead describing gun stores as “victimized” by burglaries and thefts.

In the discussion, Keane also highlighted the fact that NSSF matches rewards for information leading to arrest of people involved in those burglaries, and Richardson echoed that NSSF contributes to these rewards. These rewards create another way where ATF is dependent on the industry in order to accomplish its mission.

The discussion between Keane and Richardson demonstrates how the agency has come to act as more of a partner to, rather than an overseer of, the gun industry. It also shows a willingness on the part of ATF to participate in the industry’s endeavors, even when those efforts are not necessarily evidence-based.

For instance, NSSF has made a number of dubious claims about the positive impacts of its programs and partnerships, including claiming that Project ChildSafe, which began in 1999 as a program to distribute gun locks, deserves credit for a decrease in unintentional firearm deaths.62 Yet unintentional firearm deaths began falling before that program began, and during the same period, states were passing gun safety legislation and other organizations were engaging in educational campaigns to increase the safe storage of firearms.

By NSSF’s own admission, Project ChildSafe received over $90 million in federal funding.63 NSSF still touts the fact that the program has provided more than 40 million free firearm safety kits to gun owners, but neglects to mention that 80% of those kits were distributed almost two decades ago.64

The Atlantic reported in 2013 that when a $50 million Department of Justice grant dried up and NSSF was obliged to finance the lock giveaway on its own, the program was scaled back significantly, and some police departments severed ties with Project ChildSafe, frustrated that they’d received no locks for years, despite continuing public demand.65

Giffords Celebrates Finalization of Ghost Guns Rule

Apr 11, 2022

During the SHOT Show conversation, Acting Director Richardson also revealed non-public information to the gun industry. At the direction of President Biden, ATF began the process of strengthening its rules regarding ghost guns.66 This long overdue process represented a significant step towards addressing the threat posed by these dangerous devices. At Keane’s request, Richardson appeared to lay out the timeline for the publication of the final ghost gun rule,67 information that had not previously been made public. (The rule has since been finalized.)

That conversation was not the only indication that ATF officials often share unpublished information with industry officials. After the State Department imposed certain sanctions through restrictions on the importation of Russian-made firearms and ammunition, NSSF sent an email to its members stating, “Based on NSSF discussions with the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF), it is NSSF’s understanding that approved Form 6’s will not be rescinded and Form 6’s already submitted will be approved until Sept. 7.”68

The friendly relationship between ATF and NSSF is even more troubling given NSSF’s opposition to many gun safety proposals supported by a majority of Americans. The group has actively opposed legislation requiring background checks on all gun sales,69 banning assault weapons (which it has rebranded as “modern sporting rifles”),70 and requiring safe storage of firearms in the home71 —even while ostensibly championing safe storage practices.

As the NRA has increasingly fallen into disarray,72 NSSF has increasingly veered towards the extremist policies shared by the NRA while adopting a number of the NRA’s fanatical tactics, including framing every debate as having potentially apocalyptic consequences for gun owners.73 NSSF is particularly concerned with the need for “replacement shooters” as the gun-owning community grows older and dies out, leading it to support efforts to market guns to youth.74

Economists have explained that one of the reasons regulatory agencies tend to become captured by the industries they regulate is the threat that an industry will criticize the regulator, and this criticism will damage the regulator’s career or the agency’s ability to obtain funding. Economists refer to this type of criticism as “squawking.” When regulatory agencies fear that the industry will squawk, they tend to bend to the will of industry.75

NSSF and its leadership in particular actively demonize opponents who stand up to the gun industry so as to discourage criticism, giving up even the pretense of being an unbiased trade association. In an August 3, 2021, blog post, Larry Keane wrote a bitter, abuse-laden tirade against former Congresswoman Gabby Giffords over her support for gun safety laws and refusal to cower in the face of the industry’s growing extremism. In another post, Keane criticized CDC Director Rochelle Walensky for supporting research into gun-related issues, complaining that the CDC failed to reach out to the industry first.76

In yet another blog post, Keane attacked President Biden for his actions to assist the City of New York in its fight against gun crime. Always most concerned with the industry’s bottom line, NSSF seemed particularly focused on the President’s statement that the Protection of Lawful Commerce in Arms Act (PLCAA), which gives the firearm industry immunity from civil lawsuits, should be repealed. NSSF also chose to use the president’s efforts to save lives as an excuse to remind the public that it is legal to buy a cannon.77

Yet ATF has gone out of its way to speak positively about the industry and NSSF, actively supporting the industry’s efforts to improve its image in the eyes of the public. For example, ATF’s reward notices, in which it offers a reward for information leading to the apprehension of suspects in gun store burglaries, routinely highlight that NSSF is matching these rewards.78 In its most recent report, ATF again highlighted its partnership with NSSF to promote Operation Secure Store as an example of a “multifaceted initiative” that is “leveraging resources to enhance public safety.”79

ATF’s newest report also touted these “Firearm Industry Supported Educational Campaigns.” When discussing Project Childsafe, the report not only neglected to mention the timing of the project, but also noted that firearms manufacturers included “more than 70 million free locking devices” with new firearms sold, without mentioning that the inclusion of these devices is mandated by law.80

ATF officials who are discussing corrupt or irresponsible dealers routinely remind the public that the vast majority of FFLs are law-abiding and responsible dealers. Most recently, when ATF was revoking a license, ATF spokesman Erik Longnecker was careful to state, “The vast majority of federal firearms licensees are law-abiding businesses.”81 As discussed later in the report, ATF discovers violations of the law in almost half of its inspections of FFLs, suggesting that many FFLs are not, in fact, abiding by the law.

SPOTLIGHT

GUNS & DEMOCRACY

The use of guns to intimidate and threaten voters, elected officials, and peaceful demonstrators poses a serious threat to our democracy. We’ve gathered resources on the deadly connection between guns and extremism, and how to stop it.

Read MoreIndustry Influence over Policy

The gun industry, and NSSF in particular, have exploited ATF’s fear of squawking by making it abundantly clear how it will respond to government agents who refuse to bend to its will. This fear that the gun industry will squawk has led ATF to make many choices that put the profits of the industry over public safety. In fact, ATF has come to rely on the judgment of gun manufacturers in many encounters, treating the industry as the most important stakeholder that will be affected by its policy decisions, when in fact these decisions have tremendous implications for public safety.

At the beginning of the Trump administration, a senior ATF official authored a white paper that was leaked to the Washington Post in 2017.82 That white paper claimed to lay out proposals to “reduce or modify regulations” so as to “promote commerce and defend the Second Amendment,” admitting that “positive steps to further reduce gun violence…are not the focus of this paper.” The gun violence prevention group Brady rightly described the proposals set forth in the white paper as a “gun lobby wish list.”83 Yet it was published under an ATF seal and ostensibly authored by Ronald Turk, then-associate deputy director and chief operating officer of ATF.

Many of the proposals laid out in the white paper would be detrimental to public safety and profitable to the gun industry. Most notably, the white paper advocated for deregulating gun silencers, which disguise the sound of gunfire, making it difficult for people who are nearby, including law enforcement, to recognize and locate an active shooter. The white paper also advocated for loosening regulations of gun imports and interstate gun sales, which would make it harder for states to enforce their gun laws while opening up new markets to the gun industry.

Turk’s explanations for the various proposals ranged from the agency having a “significant backlog” in processing requests to FFLs feeling “burden[ed]” by the reporting requirements to simply “the firearms industry is opposed”—even when referencing a regulation referred to as a “viable law enforcement tool.”84

Not only were Turk’s proposals aligned with the gun industry’s profit motive,85 they were made without consideration of the actual impact the proposals might have on public safety. They also exposed the extent to which the industry has hijacked the agency, co-opting ATF’s brand to support the industry’s goals.

In March 2017, Brady submitted a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request, seeking ATF documents related to the development of the white paper.86 Around the same time, Congress launched an inquiry into the origin of the white paper.

Turk testified at a House Committee on Oversight and Government hearing in April 2017 that the issues in the white paper “had been floating around for years, from the gun industry, in particular, with ATF.”87 He explained that it felt “very important to be able to assemble the ATF executive staff to talk about key issues across the gun industry, to be able to have potential positions for the Bureau in place.” Turk denied that the NRA had weighed in on the white paper and evaded Congress’s questioning about other outside input on the white paper.88

However, the documents released by ATF in response to Brady’s FOIA request included two drafts of the white paper—an initial draft dated November 16, 2016, and an intermediate draft dated January 6, 2017—and emails between Turk and Mark Barnes, a longtime attorney for the industry.89 The initial draft proposed various regulatory changes and legislative actions that, according to Turk, “would have an immediate, positive impact on commerce and industry without significantly hindering ATF’s mission.”90 ATF also released a copy of the January 6, 2017, draft with track changes and an accompanying email in which Turk sought feedback on the draft from Barnes. The email read, in part: “If I am missing the mark on a major issue or disregarding a major discussion point any feedback you have would be appreciated.”91

It is clear that, in having ATF draft the white paper, the gun lobby sought not only to influence policymakers on these proposals but also to gain credibility for them by having them published under ATF’s seal. NSSF later published a fact sheet on legislation to deregulate silencers, highlighting a sentence from Turk’s white paper: “Given the lack of criminality associated with silencers, it is reasonable to conclude that they should not be viewed as a threat to public safety necessitating NFA calcification (sic), and should be considered for reclassification under the GCA.”92

GET THE FACTS

Gun violence is a complex problem, and while there’s no one-size-fits-all solution, we must act. Our reports bring you the latest cutting-edge research and analysis about strategies to end our country’s gun violence crisis at every level.

Learn More

ATF’s Refusal to Properly Classify Weapons

ATF also has a pattern of excessive deference to the industry when it evaluates particular firearms to determine the legal status of the technology. Within ATF, the Firearms Technology Industry Services Branch (FTISB) responds to requests from industry members regarding the classification of firearms. In particular, a firearms manufacturer or importer will often seek a determination from FTISB about whether a particular weapon is subject to the National Firearm Act’s taxation and registration requirements, or whether it is only subject to the much more lenient requirements of the Gun Control Act. ATF received 450 requests from industry members for classification of a total of 677 firearms or firearm parts in 2019 alone.93 The FTISB tests and assesses the weapon, and then sends the industry member a letter with its determination about whether the weapon falls under the NFA. ATF does not generally make these letters public, but it is common for members of the industry to do so, in order to calm the concerns of potential buyers.

The content of previous ATF classification letters that have been made public not only demonstrates the agency’s submissiveness to the gun industry, but also a lack of commitment to both the law and public safety. ATF frequently relies on a manufacturer’s statements regarding the design and intent of a weapon in deciding whether or not the weapon is subject to the NFA. The gun industry has taken advantage of this deference by spawning deadlier and deadlier devices, creating a slippery slope towards the acceptance of these devices by exploiting ATF’s unwillingness to draw the line. Sometimes ATF’s deference to the industry in its classifications has tragic consequences.

Starting in about 2008, ATF received repeated requests from industry members regarding so-called bump-fire devices, or bump stocks, which the gun industry claimed were designed to help people with limited hand mobility fire a rifle. In reality, a bump stock enables a rifle to replicate the firing pattern of a machine gun by eliminating the need for a shooter to activate the trigger separately for each shot. Yet FTISB repeatedly rejected the notion that bump stocks are subject to the NFA, instead repeating the industry’s claims that the absence of a “spring” or “coil” in these devices precluded the NFA from applying to these devices.94

Giffords Law Center Reacts to Judicial Decision Upholding a Federal Ban on Bump Stocks

Apr 01, 2019

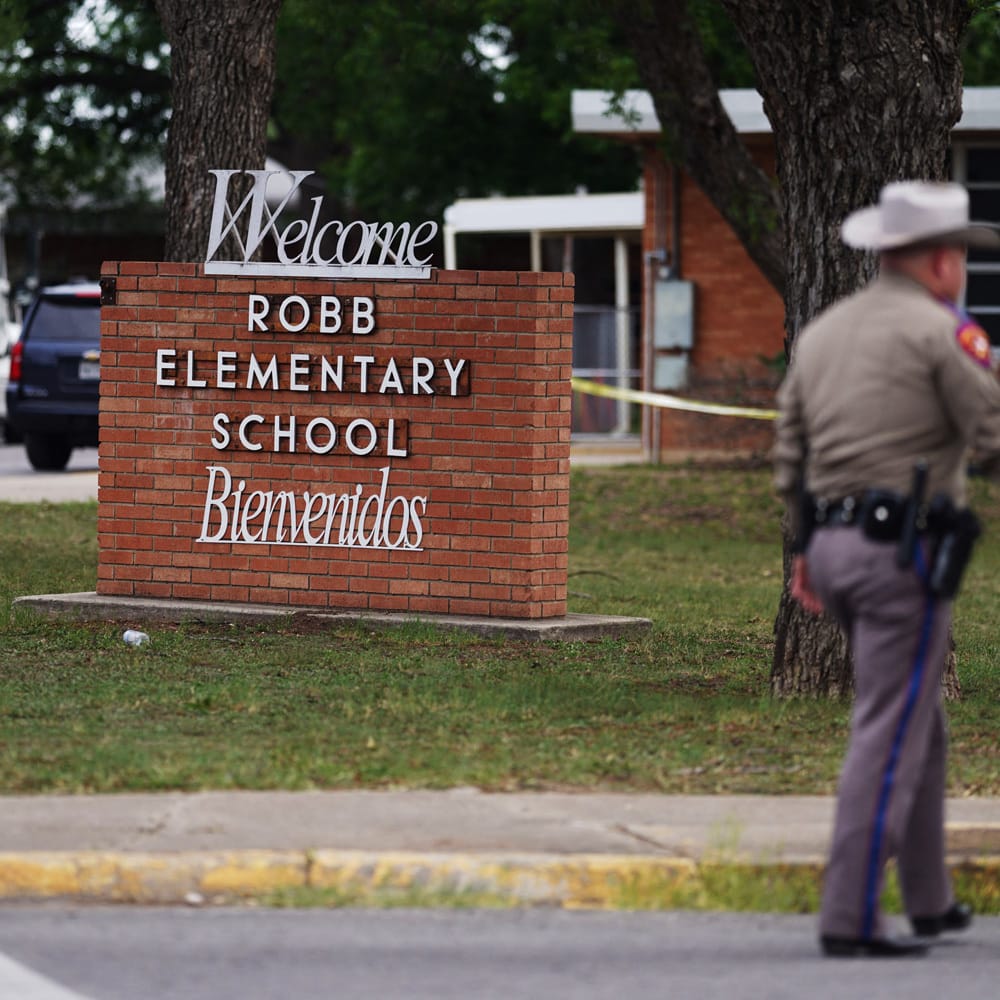

On October 21, 2017, a gunman in Las Vegas, Nevada, used firearms equipped with bump stocks to fire more than 1,100 rounds of ammunition into a crowd gathered at a country music festival, shooting more than 400 people and murdering 58 in a matter of minutes. After widespread outcry, ATF finally used its rulemaking authority to change its position, making clear that bump stocks are subject to the same laws as machine guns.95

ATF was similarly led astray by the industry’s claims regarding arm braces, also called stabilizing braces. The industry claims that these devices are intended to assist in the firing of pistols, specifically to help people with disabilities with one-handed firing.96 However, the designs of some of these devices have now been shown to allow the user to fire from the shoulder, making these weapons short-barreled rifles subject to regulation under the NFA.97 For several years, ATF deferred to the industry’s claims, agreeing to the industry’s unsupportable assertions about how these weapons would be used.98

In December 2020, ATF under Attorney General William Barr attempted to clarify its position by publishing a notice entitled “Objective Factors for Classifying Weapons with “Stabilizing Braces.”99 The NRA and NSSF reacted immediately, and their allies in Congress sent a letter to ATF and Barr to demonstrate disapproval.100 On December 23, 2020, Barr resigned from his position, and one week later, ATF withdrew the notice,101 ceding to the gun lobby’s demands and allowing the NRA and NSSF to take credit.102

Recent Polling Shows Voters Demand Stronger Gun Laws

May 26, 2022

It was not until after President Biden took office and a gunman killed 10 people at a grocery store in Boulder, Colorado, in March 2021 using an AR-15-style pistol that had been modified with an arm brace,103 that ATF finally issued a proposed rule that would set a standard for when these braces cause a firearm to fall under the regulation of the NFA.104

While ATF’s proposed rule about arm braces is a positive step, ATF has yet to fully reform the process for making determinations about whether new devices fall under the NFA. As a result, the gun industry continues to rely heavily on manufacturers’ claims about their designs and intent, and public safety experts are not generally given an opportunity to provide input before ATF issues a classification ruling.

Until ATF creates a new process through which members of the public can dispute the industry’s claims and present their own concerns about particular devices to the agency, ATF should refrain from issuing classification rulings about new devices.

ATF’s Struggle to Inspect Gun Stores

One of ATF’s most important jobs is inspecting federal firearms licensees (FFLs), including gun importers, manufacturers, and dealers. During an inspection, ATF’s “industry operations investigator” (IOI) reviews the records for all sales transactions by the FFL in the past year to ensure that it has conducted background checks on all firearm purchasers and that the sales are properly recorded. The IOI then issues a report noting any violations of the law and, if appropriate, makes a recommendation for an administrative action against the FFL. The IOI can recommend that the FFL receive a warning letter or be required to attend a meeting with ATF officials, or that the FFL’s license be revoked.105

MEMO: ATF at a Time of Transition: Underfunded and Unduly Restricted

Apr 25, 2019

Given the imbalance between the industry’s growth and ATF’s relatively stagnant size, it is no surprise that ATF has struggled to fulfill these responsibilities. However, as the Center for American Progress has argued, the lack of staffing and overall funding for ATF does not adequately explain why so little of ATF’s budget focuses on its unique role providing oversight of the gun industry.106 The vast majority of ATF staff is focused on criminal investigations and enforcement, a mission it shares with other federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies, rather than industry regulation. According to its most recent fact sheet, in 2020, ATF employed 2,653 special agents, but only 760 industry operations investigators, who are responsible for inspecting both FFLs and explosives licensees.107 As a result, ATF is able to inspect only about 10–15% of active FFLs each year.108

ATF’s Failure to Discipline Corrupt Dealers

In the context of its infrequent inspections of gun dealers, ATF has repeatedly faced criticism for failing to aggressively enforce the laws governing these firearms businesses. In fact, records show that almost all FFLs that have violated the law were allowed to continue operating. The agency’s failure to discipline corrupt gun dealers paints a clear picture of an agency that lacks the will to properly regulate the industry, even in situations where it has the resources and legal authority to do so.

As noted above, ATF is only able to inspect a fraction of FFLs each year. The infrequency of regular compliance inspections interferes with ATF’s ability to use them to effectively deter or detect dealers’ violations of the law. FFLs can sell guns for years without an inspection, allowing violations to go unnoticed and guns to be sold illegally.

Many FFLs routinely flout the law. Out of all the inspections conducted by ATF between 2010 and 2019, at least a third—35,500—found dealers had violated state and federal firearm laws.109 More recent data confirms this behavior. According to ATF’s most recent report, ATF noted violations of the law in 48% of the FFL compliance inspections it conducted between 2016 and 2020, including failures to conduct background checks, view buyer’s identification, maintain records of sales, and report multiple sales of handguns.110

Giffords Urges Passage of Senate Deal on Gun Safety

Jun 12, 2022

However, even when an inspection exposes an FFL’s legal violations, including violations that endanger the public, ATF rarely takes strong action against the dealer. In 2018, the New York Times reported that senior ATF officials routinely overrule the agency’s own investigators when they recommend license revocations, allowing FFLs that brazenly violate the law to stay open.111

That article, which was based on interviews with more than half a dozen current and former law enforcement officials and a review of more than 100 inspection reports, determined that supervisors within ATF routinely downgraded inspectors’ recommendations that licenses be revoked.112 The article explained that ATF is only authorized to revoke a license if the FFL has “willfully” violated the law.113 According to the article, supervisors feel this legal threshold, which can only be met if ATF can prove that the FFL knew they were acting illegally, makes revocations difficult to defend in court.

An even more damning picture of ATF’s inspection program emerged from an investigation published in May 2021 by USA Today, in collaboration with The Trace.114 That article was based on a review and independent analysis of over 2,000 gun dealer inspection reports that showed violations from 2015 to 2017. The violations detailed in the reports, which were obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request filed by Brady, often involved failures to conduct background checks on gun purchasers or failing to wait for those checks to be completed.115

Like the New York Times article, the USA Today investigation detailed ATF’s lax enforcement and tolerance for gun sellers who violate the law. However, that article detailed many instances where the evidence clearly showed that the FFL has willfully violated the law, and ATF had unmistakable authority to revoke an FFL’s license but failed to do so. According to the article:

“A Florida gun dealer got in trouble for giving a Taurus handgun to a convicted felon in the parking lot, and an Arkansas pawnshop was cited for selling a firearm to a customer even though he’d failed the background check because of an active restraining order. In Ohio, one store transferred guns without conducting background checks 112 times; another was missing some 600 firearms. A Pennsylvania gun retailer racked up 45 violations and received eight warnings from the ATF. But the store was allowed to remain in business, and it went on to sell a shotgun to a man who used it to kill four family members, including his 7-year-old half-brother.”116

Overall, the documents obtained by Brady and reviewed by reporters showed that ATF rarely revokes the licenses of even the most egregiously noncompliant FFLs. Based on those documents, ATF inspectors found that only about three percent of FFLs cited for violations met ATF’s internal criteria for revocation. After officials downgraded more than half of those revocation recommendations, ultimately only half a percent ended up having their licenses revoked, meaning that approximately 99% of FFLs found to have violated the law were allowed to stay open.117

Instead, ATF routinely gives noncompliant gun dealers multiple chances over a period of years to correct violations, including serious violations such as selling guns to minors, failing to report missing or stolen guns, and neglecting to conduct background checks. During that time, the noncompliant FFL continues to sell guns.

A separate investigation published on April 11, 2022, by USA Today in collaboration with The Trace showcased multiple instances of dealers receiving multiple chances to correct violations.118 The investigation reviewed ATF inspection records for 13 gun dealers identified by Chicago as suppliers of a disproportionate number of guns used in crime.

One Indiana dealer was inspected by ATF four times between 2000 and 2009, and each time ATF only issued warnings. The dealer’s violations included selling to underage customers, selling to someone who identified themself as a convicted felon, failing to submit a multiple sales report, failing to properly record firearm transfers, and “aid[ing] the making of false statements” on a Form 4473 in order to sell to a person acting as a straw purchaser. Between 2013 and 2016, Chicago police recovered more than 130 guns that could be traced back to this dealer.

ATF inspected another Indiana dealer eight times between 1989 and 2011, continuously uncovering the same problem—the failure to accurately record sales, which is often an indicator of gun trafficking. In 2012, inspectors recommended revoking the dealer’s license, which was supported by the inspector’s superiors, but ATF never followed through. A 2013 inspection uncovered the same violation, in addition to straw purchase sales and knowingly falsified sales logs. Again, inspectors recommended revocation, but instead a warning was issued. In the three years following the 2013 inspection, more than 340 guns from this dealer were found at Chicago crime scenes.

Senate Proposal on Gun Violence Prevention

Jun 12, 2022

The records released in this investigation dated as far back as 2009, suggesting ATF’s lax approach to investigating and enforcement, as well as its tolerance of irresponsible gun dealers, is not new.119

Newly released data from ATF confirms this pattern. When ATF found violations in compliance inspections it conducted between 2016 and 2020, it responded by issuing a report and taking no further action 36% of the time. Another 24% of the time, it only issued a warning letter.120

ATF’s failure to revoke the licenses of corrupt FFLs also has troubling racial overtones. Documents obtained by the Brady Center suggest that the FFL community is disproportionately white. As of early 2020, 86% of the individuals responsible for operating FFLs in California were white, and the numbers for New Jersey (96%), Wisconsin (94%), and Washington DC (100%) were similar.121 Given that gun violence disproportionately impacts Black and Brown Americans, the overwhelming whiteness of the industry that profits from the sales of firearms makes the question of why ATF is so reluctant to revoke licenses from corrupt FFLs even more urgent.

Clearly, the explanation for ATF’s reluctance to revoke FFLs’ licenses lies beyond the legal constraints on its authority and points to the industry’s influence over the agency. ATF officials have claimed to be giving some FFLs the benefit of the doubt because they have been in business so long, while giving other FFLs the benefit of the doubt for the exact opposite reason: because they have only recently entered the business.122 ATF officials have also cited the FFL’s age, health problems, or willingness to work with ATF to improve their practices as reasons for their lenient approach in individual cases.

Despite this litany of excuses, ATF officials have sometimes spoken with more candor. They have mentioned that they fear litigation from the FFLs or a “backlash” against the agency, as well as concerns over the potential for Congress to further limit ATF’s funding. The USA Today article quoted Howard Wolfe, a former ATF supervisor who oversaw inspections in Pittsburgh as saying, “ATF is a very small agency, a very unpopular agency, and as a result, there are a lot of people trying to push them around.”123

According to Mark Jones, who held various supervisory positions at ATF before retiring in 2012, “they shrug off serious violations and say they’re not a big deal because they don’t want to upset the industry too much.”124

It’s clear that ATF’s inspection program fails to inspire trust among those concerned about public safety. The low rate of revocations and slow progress towards revocations enables too many guns to flow out of the stream of legal commerce, a situation which has not gone unnoticed by NSSF. According to an NSSF fact sheet:

John Jarowski, a former industry operations director in St. Paul, Minnesota, was quoted in the USA Today article blaming the low rate of revocations on US Attorneys: “Many times when the U.S. Attorney steps in he’d say, ‘This dog won’t hunt,’ and they’d drop it.”126

Some US Attorneys may, in fact, be discouraged from defending a license revocation by the “willfulness” requirement. Leaders within DOJ should ensure that US Attorneys, as well as ATF officials, prioritize defending license revocations, since corrupt FFLs that continue to sell guns present a serious danger to the public.

This situation has also not gone unnoticed in the highest realms of government. As President Biden said in June 2021, “Today, enough rogue gun dealers feel like they can get away with selling guns to people who aren’t legally allowed to own them.” He later added: “These merchants of death are breaking the law for profit. They’re selling guns that are killing innocent people. It’s wrong. It’s unacceptable.”127

President Biden announced several executive actions to increase the effectiveness of ATF’s inspections, calling on ATF to:

- Obtain leads from state and local law enforcement regarding dealers who may not be complying with the law

- Formalize the use of data-driven prioritization of inspection resources

- Provide data from ATF’s inspections of dealers to state agencies that also oversee those businesses

- Provide the public with more data about ATF’s inspections128

Most importantly, the president announced a zero tolerance policy for rogue gun dealers that willfully violate the law.129 ATF subsequently issued a new guidance document setting out the parameters of this new policy. According to that document, absent extraordinary circumstances, ATF will issue a notice of revocation whenever it determines an FFL has willfully committed certain violations, including failing to conduct a required background check or falsifying records.130

While these actions are a step in the right direction, it is clear that ATF needs a fundamental change in culture and leadership in order to shift its practices and shake off the influence of the industry.

LItigation

the courts

Explore our work defending lifesaving gun laws in the courts and fighting to debunk the gun lobby’s dangerous arguments about the Second Amendment.

Lack of Leadership

As noted earlier, ATF has had only two Senate-confirmed directors since 2006, making the agency more susceptible to outside pressure and reducing the agency’s ability to maintain a commitment to its core objectives.

After 9/11, Congress moved ATF from the Department of the Treasury into the Department of Justice, where it was determined that ATF would have a director under the authority of the attorney general.131 At first, the attorney general could simply appoint the director. However, in 2006, the National Rifle Association lobbied for and Congress enacted a new law requiring the ATF director to be appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate.132 This requirement subjected the agency to political whims and made it significantly harder for the agency to maintain steady leadership.

The gun lobby then succeeded in opposing a number of well-qualified nominees to lead the agency, including a US Attorney nominated by the Bush administration, the head of the ATF Chicago division nominated by the Obama administration,133 and most recently, David Chipman. Forced to deal with this unrelenting gun lobby opposition, the agency has now seen nine different directors since 2006—seven of whom served on a non-permanent, non-confirmed basis. NSSF has been happy with the result, stating:

When President Biden took office, the White House recognized the need for a permanent ATF director. The president nominated David Chipman, a former ATF special agent and 25-year veteran of the agency.135 Chipman was extremely well-qualified for the position, having served on ATF’s SWAT team and worked on many high-profile firearms trafficking cases (at the time of his nomination, David Chipman served as a senior advisor to Giffords).

NSSF almost immediately went on the attack, claiming Chipman was a “terrible choice” and “wholly unqualified.” Most tellingly, NSSF stated that the nomination was “a troubling reversal of years of pro-active safety cooperation between ATF and our industry” and a “reckless betrayal.”136

When the Senate Judiciary Committee held a hearing on the nomination, NSSF made clear that it was counting the votes and would consider a vote in favor of confirmation to be a sign of “anti-gun bias.”137 NSSF repeated salacious accusations linking Chipman with Chinese propaganda.138 and NSSF’s Larry Keane posted a photo of an FBI agent in front of the ruins of the 1993 Waco siege, falsely claiming the agent was Chipman139 (Keane later admitted this claim was false140). As a result of this falsehood, Chipman and his family received death threats.141 On September 9, 2021, President Biden withdrew Chipman’s nomination.

On April 11, 2022, President Biden announced his nomination of Steve Dettelbach to serve as ATF director. Dettelbach is a highly respected former US Attorney who was unanimously confirmed for his position as US Attorney in 2009 and has a history of working with federal, state, and local law enforcement to fight violent crime and combat domestic violent extremism and religious violence. He worked in partnership with ATF to prosecute complex cases and with local law enforcement and community leaders to implement community-driven efforts to reduce and prevent violent crime.

Once again, despite these qualifications, NSSF wasted no time communicating its “significant concerns” with Dettelbach’s previously stated positions on various gun safety policies, citing universal background checks, an assault weapon ban, and extreme risk protection orders, three policies that all enjoy support from a majority of Americans.142

In spite of this aggressive opposition, the Senate refused to bend to the will of NSSF and confirmed Dettelbach as ATF director. With strong, permanent leadership in place, the agency has a much better chance of righting many of the wrongs explored in this report, from failing to investigate FFLs, to failing to discipline them, to failing to properly classify dangerous weapons and devices.

RESIST THE GUN LOBBY

Need a hand fighting the gun lobby in court? Whether it’s empowering survivors to fight back against harmful laws or helping government officials defend lifesaving gun policies, the Giffords litigation team is here to help.

CONTACT USLack of Transparency

ATF’s role gives it unique insight into larger nationwide trends in gun trafficking that state and local law enforcement agencies don’t have. Along with this role comes a responsibility to inform the public about these trends, so that policymakers and the public can properly focus their own efforts to reduce gun violence in their communities. Unfortunately, in recent years, ATF’s close relationship with the gun industry has been bolstered by a lack of transparency within ATF. The agency’s refusal to provide information to the public about its inner workings has often shielded it from scrutiny, benefiting the gun industry at the expense of the public.

Twenty years ago, ATF released a comprehensive report on trends in its gun trafficking investigations entitled Following the Gun: Enforcing Federal Laws Against Firearms Traffickers.143 This report, which was based on an analysis of the ATF’s criminal investigations into gun trafficking from 1996 through 1998, provided invaluable information about illegal gun trafficking that policymakers have relied on ever since.

Among other things, Following the Gun noted that FFLs are “a particular threat to public safety when they fail to comply with the law.” Although they were involved in under 10% of the trafficking investigations described in Following the Gun, these businesses were associated with the largest number of diverted firearms—over 40,000 guns.144

Until recently, ATF had not issued an updated report in the past 20 years, depriving policymakers of the information they need to address the threat posed by gun traffickers—including corrupt FFLs who divert firearms out of legal commerce.

In April 2021, President Biden announced that ATF would issue a new, comprehensive report on firearms trafficking,145 a positive and long overdue step towards greater transparency from ATF. On May 5, 2022, ATF released the first volume of a four volume report intended to fill this role.146 This report reveals several new data points that may seem unfavorable to the industry or ATF, including:

- ATF’s firearms license fees have not increased since 1993. If adjusted to current values using the Consumer Price Index, the fees would have increased nearly 99%. NFA taxes, unchanged since they were set at $200 in 1934, would be $4,200.147

- On average, 30% of licensed manufacturers failed to provide the required report regarding the number of firearms manufactured between 2016 and 2020.148

- 45,346 firearms were reported missing by FFLs between 2016 and 2020. Only 2.6% of those firearms have been recovered.149

- 36% of licensed dealers, 33% of licensed manufacturers, and 23% of licensed importers operate from a residential (as opposed to commercial) location.150

- A small group of FFLs violate the law egregiously. Between 2016 and 2020, ATF identified a total of over 65 million violations during 13 FFL compliance inspections alone. (The report does not specify how ATF responded to those violations.)151

- ATF lacks a data system to track information it receives about imported firearms and fails to follow up with FFLs who fail to report imported firearms as required.152

Yet there are many other forms of information that ATF continues to withhold from public view. As noted above, ATF does not publish its NFA classification rulings and has only recently begun releasing its FFL inspection reports in response to Freedom of Information Act requests.

As The Trace has reported, there are also persistent problems with ATF’s ability to respond to Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests.153 The FOIA request process requires federal agencies to respond to a request within 20 business days except in the case of “unusual circumstances.” If additional time is needed to fulfill the request, an agency is supposed to notify the requester in writing.

But ATF frequently ignores FOIA requests, violating the law154 and making it harder for citizens, journalists, and researchers to monitor the agency’s activities. In 2020, ATF failed to respond to 250 FOIA requests out of the 1,200 submitted.155 ATF had the fifth-longest processing time for complex requests among 76 agencies that completed 500 or more FOIA requests in 2020. Almost half of ATF’s FOIA request processed were backlogged, compared to less than one-fifth among agencies across the federal government.156

When ATF does respond to a FOIA request, it often takes months, if not years, to provide even simple information. Other times, ATF’s reticence in response to FOIA requests leads to lawsuits, and ATF only responds when the matter ends up in court. As summarized by a former ATF agent, “[ATF] follow[s] the policy of give nothing, and make the requester fight for it.”

ATF’s failure to comply with FOIA requests conceals its own wrongdoings and protects dealers that are contributing to the gun violence epidemic. ATF has often pointed to the legislative riders that limit its ability to manage its information as an explanation for its poor record of responding to FOIA requests. However, these riders do not fully explain the long delays in ATF responses, as at least one court has pointed out.

In 2017, a lawsuit was filed after ATF stopped responding to a FOIA request seeking statistics on guns once owned by law enforcement being used in crimes. ATF argued that it was not authorized to run a search query to collect data from its databases, so it was not required to respond to FOIA requests that would necessitate such search queries. In 2020, a Ninth Circuit Appellate Court ruled against the agency, with the author of the majority opinion writing, “[w]ere we to agree with ATF that the results of a search query run across a database necessarily constituted the creation of a new records, we may well render FOIA a nullity in the digital age.”157

In 2017, Brady filed a lawsuit when ATF failed to fulfill a FOIA request seeking documents related to the development of the white paper authored by Ronald Turk described above,158 after six months and repeated follow-up attempts.159 In 2021, four years after Brady first filed its FOIA request, ATF’s production of relevant documents was ongoing; ATF even acknowledged that reports were missing. This slow and inconsistent production of requested documents is not an anomaly—as of September 2020, ATF had 16 pending FOIA lawsuits.160

Access to ATF’s records helps inform the public of the agency’s strengths and weaknesses. The solicitation of records and expectation that records will become public also puts the industry on notice that it will not be able to get away with not complying with federal law. Unfortunately, the full extent of gun dealers’ noncompliance with the law and of ATF’s failure to regulate gun dealers, and thus its contribution to the gun violence epidemic, will likely never be known unless ATF improves its compliance with the FOIA.

ATF’s poor record of transparency can be attributed in part to a lack of resources, since staff must gather and review records before they are released. Nevertheless, the extent of ATF’s reluctance to provide information to the public suggests another explanation: a desire to avoid scrutiny. In fact, not only does ATF’s reticence protect ATF from criticism, it also shields the firearms industry.

While NSSF openly touts the presence of ATF at the SHOT Show, the SHOT Show is not open to the public. As a result, the public only knows what NSSF or ATF wants it to know about the conversations that happen there. The SHOT Show is not the only time the gun industry communicates with ATF behind closed doors, as demonstrated by the process that led to the drafting of the 2017 white paper. As described above, Mark Barnes, an attorney for the gun industry, worked closely with Ron Turk, the ATF official drafting the paper.

In addition, ATF officials are just some of the federal agency officials who were scheduled to appear before gun industry members at the annual “Orchid Advisors Firearms Industry Compliance Conference” held in Atlanta on April 25–27, 2022, in addition to speakers from the FBI and the Departments of Commerce and State.161 ATF officials also spoke with FFLs at 306 “warning conferences” in fiscal year 2020, according to ATF’s own website detailing the results of its inspections of FFLs.162 According to a recent report from ATF:

It is clear that private discussions between the gun industry and ATF officials are common, and the public is often left out of these discussions.

Researchers who tackle the problem of agency capture have often concluded that transparency about an agency’s methods, activities, and results can help prevent agency capture. ATF has a long way to go in this regard.

HERE TO HELP

Interested in partnering with us to draft, enact, or implement lifesaving gun safety legislation in your community? Our attorneys provide free assistance to lawmakers, public officials, and advocates working toward solutions to the gun violence crisis.

CONTACT US

How to Fix ATF

In order to ensure that ATF remains focused on its mission and serves public safety first, certain actions must be taken to free the agency from the influence of the gun industry.

Leadership within DOJ must steer ATF back towards its mission, and ensure that it takes a more aggressive stance towards members of the gun industry who flout the laws and endanger public safety. It is possible for an agency to resist the tendency to become dominated by the industry it regulates. DOJ needs to take the reins over ATF back from NSSF and enable ATF to shake off the pernicious influence of those who put profits above public safety.

Giffords Calls on Senate to Confirm Dettelbach

May 25, 2022

Congress should repeal the restrictions on ATF that have provided the agency with convenient excuses for failing to do its job, such as the restrictions on physical inventory requirements for gun dealers and on the release of gun trace data. These restrictions are giving ATF officials too many opportunities to dodge their responsibilities, like their duty to revoke licenses from corrupt gun dealers. Congress should also remove the “willfulness” limitation on ATF’s authority to revoke licenses from dealers who have repeatedly flouted the law.

Congress should update the language of the National Firearms Act to address newer weapon designs. The law should also be changed to give ATF clear authority to address the manner in which gun dealers and other FFLs store their firearms in order to prevent thefts, and train their employees to ensure they properly conduct background checks, maintain records, and identify straw purchases.

Congress should promptly exercise its oversight authority to address the issues raised in this report and hold ATF officials to account for their performance. Congressional committees can and should hold hearings in order to gauge the extent of the relationships that have developed between representatives of the gun industry and ATF officials, and the degree and impact of the gun industry’s influence over ATF’s decision making.

However, even without legislative action, there is authority within the executive branch, in particular within the Department of Justice, to change ATF practices. ATF has actively resisted efforts to transfer any of its functions, missions, or activities to other departments within DOJ by requesting the inclusion of an annual appropriations rider to this effect. At ATF’s request, Congress has included this rider every year, effectively prohibiting DOJ from shifting some of ATF’s responsibilities to other agencies.164 ATF should stop requesting that rider, so that other agencies within DOJ can assist ATF in fighting gun violence.

DOJ can also support and overhaul ATF by:

- Providing stronger legal and administrative oversight

- Holding those in leadership positions within ATF accountable for results

- Ensuring the licenses of irresponsible FFLs are promptly revoked

- Vigorously defending ATF against gun lobby attacks

- Advocating for more funding for ATF

- Providing ATF with support for its gun trafficking investigations from the FBI, US Marshals, and other federal law enforcement agencies, including by detailing officers from those agencies to increase ATF’s capacity for those investigations

- Ensuring that ATF engages with public safety advocates

- Providing the public with complete data

As gun violence continues to rise across the country, we don’t have a moment to waste. We need look no further than the opioid epidemic and environmental disasters of the BP oil spill to understand the truly devastating repercussions of agency capture, and as this report has laid out, evidence points to ATF being in a similar, extremely dangerous position. As public safety advocates, we must clearly and repeatedly demand a different, better way forward for ATF and for our country.

MEDIA REQUESTS

Our experts can speak to the full spectrum of gun violence prevention issues. Have a question? Email us at media@giffords.org.

Contact

- Daniel Nass and Champe Barton, “How Many Guns Did Americans Buy Last Month? We’re Tracking the Sales Boom,” The Trace, March 1, 2022, https://www.thetrace.org/2020/08/gun-sales-estimates/.[↩]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (WONDER), “Underlying Cause of Death, 1999–2020,” last accessed January 3, 2022, https://wonder.cdc.gov/.[↩]

- See Chelsea Parsons and Arkadi Gerney, “The Bureau and the Bureau,” Center for American Progress, pp. 8–9, May 19, 2015, https://americanprogress.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/ATF-report-webfinal2.pdf?_ga=2.196855788.1309643509.1648588664-2090723993.1635971962.[↩]

- Id.[↩]

- For a comprehensive discussion of agency capture, see Ernesto Del Bó, “Regulatory Capture: A Review,” Oxford Review of Economic Policy 22, no. 2 (2006): 203-225, http://faculty.haas.berkeley.edu/dalbo/Regulatory_Capture_Published.pdf; See also “Protecting the Public Interest: Understanding the Threat of Agency Capture,” Transcript of hearing before the Committee on the Judiciary, US Senate, August 3, 2010, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-111shrg64724/html/CHRG-111shrg64724.htm.[↩]

- Yong Gyo Lee, Xavier Garza-Gomez, and Rose M. Lee, “Ultimate Costs of the Disaster: Seven Years After the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill,” The Journal of Corporate Accounting and Finance 29, no. 1 (January 2018): 69-79, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/jcaf.22306.[↩]

- See, e.g., Farhad Manjoo, “America Desperately Needs a Much Better F.D.A.,” New York Times, September 2, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/09/02/opinion/fda-drug-approval-trust.html.[↩]

- Charles P. Pierce, “‘Regulatory Capture’ Sounds Boring Until Airplanes Start Falling Out of the Sky,” Esquire, September 16, 2020, https://www.esquire.com/news-politics/politics/a34045023/boeing-737-max-regulatory-capture/.[↩]

- Pub. L. No. 90-618 | 82 Stat. 1213 (1968).[↩]

- 18 U.S.C. § 922(a), (b).[↩]

- 18 U.S.C. § 923.[↩]

- Pub. L. No. 103-159, 107 Stat. 1536 (1993) (codified at 18 U.S.C. § 922(t[↩]

- “Federal Firearms Licensee (FFL)Theft/Loss Report: January 1, 2020 – December 31, 2020,” Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, https://www.atf.gov/firearms/docs/undefined/federalfirearmslicenseeffltheftlossreportjan2020-dec2020508pdf/download.[↩]

- Pub. L. No. 99–308, 100 Stat. 449 (1986).[↩]

- 18 U.S.C. § 923(g)(1)(B)(ii)(I).[↩]

- 18 U.S.C. § 926(a).[↩]

- Pub. L. No. 73-474, 48 Stat. 1236 (1934).[↩]

- “Firearm Types Recovered and Traced in the United States and Territories (xcl),” Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, last accessed April 20, 2022, https://www.atf.gov/resource-center/firearms-trace-data-2020.[↩]

- 18 U.S.C. § 923(g)(7).[↩]

- 18 U.S.C. § 926.[↩]