A Drastically Altered Landscape: How Recent Policy Developments May Affect Gun Violence Rates

Within a matter of hours on June 23, 2022, the landscape of gun violence prevention laws in the United States shifted drastically.

That day, the Supreme Court issued an extremist, ahistorical opinion in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association Inc. v. Bruen, imposing the gun lobby’s dangerous “guns everywhere” agenda on the public. Shortly thereafter, Congress passed the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act, its first significant gun safety legislation in nearly 30 years.

With these two changes, the country took a significant step forward in passing the kinds of gun safety laws needed to protect public safety while also seeing a broadening of gun rights that will lead to more crime and violence. This analysis sets forth some of the factors that may contribute to increased gun violence, and those that may ameliorate it.

Identifying the effects of these actions will take time and will require controlling for other phenomena that affect rates of gun violence. One study of state firearm laws, for example, indicates that it takes an average of seven years for states to see a reduction in firearm homicide risk following the enactment of gun safety laws.1 In fact, evidence suggests that in some cases, it can take several months or years for states to fully implement gun safety policies, particularly those which take education, training, and compliance from local actors.2

Implementation Toolkit for Gun Safety Laws

Julia Weber—Jul 12, 2021

Additionally, the impacts of some policies may grow over time. For example, the Bruen decision may have a short-term impact of increasing the number of Americans who carry guns in public. However, over time, the decision could influence an even larger number of Americans to carry guns in public, as some people who have historically felt safe in their communities may begin to feel that they too should carry a gun to protect themselves from the growing number of armed people around them.

Further complicating the question of how these policy changes will impact gun violence is the fact that gun deaths have fluctuated widely from historical averages in the last two years. The gun death rate rose 15% in 2020, resulting in more than 45,000 deaths.3 Preliminary data suggests that gun deaths continued to rise in 2021.4 These changing dynamics in gun deaths—and the uncertain temporality of these trends—will further complicate efforts to isolate the impacts of these new policy changes.

Future studies from trained researchers will be needed to accurately describe the effects of these policy changes. In the meantime, however, extant research and data can provide some clues into the impacts these different policy changes are likely to have. Importantly, a large and ever-growing body of studies show that where there are more guns there is more gun violence5 and that states with strong gun laws have lower rates of gun violence compared to states with weaker laws.6 Additionally, specific policy research and evidence can also suggest potential impacts we are likely to see over the coming years.

MEDIA REQUESTS

Our experts can speak to the full spectrum of gun violence prevention issues. Have a question? Email us at media@giffords.org.

Contact

Bipartisan Safer Communities Act

On Saturday June 25, 2022, President Biden signed the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act into law. This monumental package enacts a number critical gun safety provisions, including:

- Supporting state implementation and establishment of extreme risk laws—which enable courts to temporarily suspend an individual’s access to firearms—with $750 million in federal funding

- Addressing the so-called “boyfriend loophole” by prohibiting dating partners convicted of misdemeanor domestic violence crimes from buying or possessing guns

- Providing $250 million over five years for community violence intervention (CVI) work to support coordinated, evidence-informed, community-based intervention and prevention programs

- Establishing an enhanced background check process for buyers under age 21 that will require additional investigative steps to review juvenile records and consult with local law enforcement before the sale of a long gun can proceed

- Establishing federal statutes to clearly define and penalize firearms trafficking and straw purchasing

- Clarifying language to require people selling guns for profit to obtain a license and conduct background checks

Many of these policies expand on current solutions to gun violence that are both evidence-based and well-researched. For example, research on extreme risk laws suggests that these policies can play a critical role in helping to prevent both firearm suicides and mass shootings. Studies have found that for every 10 to 20 orders issued under these laws, one life is saved through an averted suicide,7 with one study showing that these laws may translate into population-level reductions in gun violence.8 Research also suggests that these laws may be effective in preventing mass shootings.9

Expanding firearm prohibitions to convicted abusive dating partners is also an effective, evidence-based measure. Multiple studies have shown that prohibiting abusive partners from purchasing or possessing firearms can help prevent intimate partner homicides.10 One analysis found that states which fully close the so-called “boyfriend loophole” experience 16% fewer intimate partner gun homicides.11

The expansion of funding for CVI programs is another provision rooted in a strong and ever-growing evidence base. Studies of these interventions have found them to be remarkably impactful, resulting in sizable, sustainable reductions in community violence when properly funded and scaled.12 For example, one CVI program at a South Bronx, New York, site experienced a 37% decline in gun injuries and a 63% reduction in shooting victimizations, relative to a comparison neighborhood.13

Other components of this bill have not been specifically evaluated, but are based upon sound scientific evidence. For instance, the enhanced background check process for purchasers under age 21 may help reduce the risk of young people using a gun in an act of violence. People ages 18 to 20 are responsible for a disproportionate share of school shootings,14 public mass shootings,15 and gun homicides overall,16 suggesting that additional screening of this group may be warranted.

There is also reason to believe that people with juvenile records may be at elevated risk of firearm suicide, with one study showing that individuals incarcerated before age 18 were at increased risk of suicide compared to individuals who had never been incarcerated or were older at the time of incarceration.17 Importantly, research suggests that denying the sale of a firearm to a prohibited person can significantly reduce their risk of future gun violence.18

Data has also shown that gun trafficking is a substantial driver of crime that can serve to undermine strong gun laws.19 Research indicates that preventing gun trafficking can impact the illegal gun market, making guns more expensive and more risky for prohibited persons to procure.20

Research also suggests that this federal action may have additional benefits, particularly by expanding gun safety efforts at the state level. Scholars have identified a phenomenon of “vertical policy diffusion,” whereby the passage of a law at the federal level pushes states to pass similar laws or laws addressing similar topics.21 One study, for example, found that states were 18% more likely to enact a domestic violence firearm law the year the Violence Against Women Act was passed, 14% more likely to enact a domestic violence firearm law in the year after this legislation, and 18% more likely to enact a domestic violence firearm law the year that VAWA’s prohibition on firearm access was extended to those convicted of a misdemeanor crime of domestic violence.22 These researchers suggested that Congress closing the “boyfriend loophole” may be one way to encourage the adoption of more domestic violence firearm laws at the state level.23

While existing research strongly suggests that this legislation will save lives, it is important to remember that there are limitations to these policy changes. For example, while this legislation will address the boyfriend loophole in the criminal context, prohibited purchasers in many states will retain an easy path to purchasing guns through private sales in the 33 states which do not require background checks on all gun sales.

Similarly, the CVI funding, while important, is insufficient to address the scourge of community gun violence facing our nation at this moment. While this funding will undoubtedly protect those who directly benefit from its funded programs, we are unlikely to see the large, quick reductions in violence that communities across the country need and deserve.

Furthermore, many of the provisions of this bill—particularly those that allocate funding to localities to address gun violence—are contingent upon strong, effective implementation. How this funding is distributed, what kind of technical assistance is provided, and how states and cities actually use this funding will ultimately determine the impact that these policies have.

Other Federal Gun Safety Efforts

In addition to this historic legislation, the federal government has also taken or is poised to take other action that will help prevent gun violence. In April, the Justice Department’s Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) finalized its ghost gun rule. Ghost guns are firearms that do not have serial numbers because they are made by private individuals rather than licensed manufacturers. These guns are an attractive source of firearms for firearm traffickers and prohibited people precisely because there are no background checks or sale records and the guns themselves are untraceable.

Militia Groups Use Ghost Guns to Skirt Federal Law

May 19, 2021

While it is too early to determine the impacts of this new rule, we know that ghost guns are playing an ever-growing role in fueling gun violence. From 2016 to 2020, more than 23,900 ghost guns were reported to ATF as having been linked to a crime, and at least 20,000 were reported during 2021 alone.24 Cities and states have reported that between 30–40% of firearm recoveries in recent years have involved ghost guns.25

This new rule will define the unfinished parts used to make ghost guns as firearms, which means that those who sell them will have to be licensed, will have to serialize them and retain records, and will have to conduct a background check before every sale. This critical rule will finally stop the flood of ghost guns at its source and should help to curb violence committed with these weapons.

Additionally, in Fiscal Year 2022, Congress established the Community Violence Intervention and Prevention Initiative (CVIPI) to support community violence intervention efforts with a $50 million appropriation. This funding marks the first time Congress has established a dedicated grant program within the Department of Justice specifically to support CVI work. As with the CVI funding in the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act, this funding is likely insufficient to substantially reduce national rates of gun violence, though there may still be measurable benefits for the communities that directly receive this funding.

Another important step is the confirmation in July 2022 of Steve Dettelbach as the permanent ATF director. ATF plays a critical role in interdicting illegal gun trafficking by regulating gun dealers, curbing unlicensed gun sellers, and disrupting trafficking channels. The agency has been without a director since 2015 and requires strong leadership in order to carry out its important work. Steve Dettelbach brings this leadership to ATF, which could help support the agency’s efforts to prevent gun violence.

State Gun Safety Actions

In addition to this critical federal action, several states have taken unprecedented steps to promote gun safety that may help reduce gun violence in the years to come. In 2021, 12 states and the District of Columbia committed significant funding for local community violence intervention and prevention programing or created offices dedicated to violence prevention. A number of states and cities also used funds from the American Rescue Plan to implement or scale CVI programs.26

Giffords: What Is CVI?

California made a particularly significant investment in community violence intervention work, dedicating $200 million in funding for the California Violence Intervention and Prevention Grant Program (CalVIP) to fund CVI work in communities across the state. Programs that have received funding through CalVIP have been credited by independent researchers with reducing homicides in cities including Oakland,27 Richmond,28 Los Angeles,29 Sacramento,30 and Stockton.31

These bold gun safety actions undertaken by states will be critical in the years to come, helping communities recover more quickly from the recent surges in violence. These programs will be most impactful if states continue to maintain stable, consistent funding.32

Receding of the COVID-19 Pandemic

The SCOTUS decision and federal gun safety legislation come on the heels of changing gun violence epidemic that shifted dramatically during the COVID-19 pandemic. In fact, gun deaths reached their highest level on record in 2020, with more than 45,000 lives lost to gun violence.33 Preliminary data suggests that gun deaths rose even higher in 2021.34 These increases in gun violence were primarily driven by an increase in gun homicides in our nation’s most impacted communities.35

Available data suggests that both the social and economic changes related to the pandemic, as well as the erosion of trust in police after high-profile killings like those of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, may have played a substantial role in creating conditions for this gun violence surge.36 Importantly, however, as the pandemic recedes and as confidence in police regresses towards pre-2020 levels,37 the factors that led to these increases may become less salient in driving crime trends.

In 2022 thus far, many cities are reporting declines in gun homicides and shootings. Gun homicides in Chicago,38 New York City,39 and Boston40 have fallen by 15%, 10%, and 41%, respectively, from January through June 2022 compared to the same period in 2021. While many major crime trends are most defined by the summer months, when shootings generally rise, these declines do suggest that the surges of recent years may be leveling out. These changing dynamics are important to consider as factors that may mask policy-related changes in gun deaths.

Supreme Court Decision in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association Inc. v. Bruen

On June 23, a conservative supermajority in the Supreme Court issued a decision in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association Inc. v. Bruen, finding that there is a constitutional right to carry a handgun outside the home for self defense. The ruling overturns a New York State law that has stood for more than a hundred years and limits the rights of states to regulate guns in public. Laws in dozens of states that require some form of licensing for concealed carry are jeopardized by this ruling.

As a result of this ruling, states that have historically had strong concealed carry licensing laws, including New York, California, Hawaii, Massachusetts, Maryland, and New Jersey, will see expanded gun carrying outside the home. Together, these states contain more than 80 million people, over one-quarter of the US population.

Research shows that states that weakened their firearm permitting laws experienced a 13–15% increase in overall violent crime rates over expected levels.41 Another study found that states that weakened their firearm permitting laws experienced an 11% increase in homicides committed with handguns—with no change observed in non-gun homicides or homicides committed with long guns, forms of violence that presumably would not change due to a law regulating handgun carriage.42

Furthermore, researchers who analyzed data from 47 cities found that when states weakened firearm permitting laws, violent firearm crime increased by 29%, with the largest increases shown in firearm robberies.43 Researchers identified weaker public carry laws impairing police effectiveness and leading to increases in gun theft as the primary mechanisms driving these increases.44 Specifically, lax public carry laws require police to deal with the abundant challenges of a more armed public, leading to a 13% decline in police clearance rates for violent crimes.45 Additionally, these lax laws led to a 35% increase in gun thefts, which research shows can be an important source of crime guns.46

Critically, the mechanisms most salient in driving violence appear to be factors that would be unleashed by even law-abiding concealed carry permit holders.47 In other words, an increase in the total number of people who carry firearms—including those who are so-called “law abiding” and those who aren’t—can lead to increases in violent gun crime.

This research is clear that this Supreme Court decision will lead to more violent crime and gun violence and cause communities to be less safe. While there may be measures that states can take to mitigate some of this risk, such as requiring additional training to obtain carry permits and expanding people who would be prohibited from carrying due to specific elevated risk factors, the reality is that we should expect to see significant increases in violent crime in the states whose laws will change most drastically as a result of this decision.

In addition to expanding public carry, this Supreme Court decision changes the framework under which gun safety laws will be reviewed by the courts. Courts will no longer be able to rely on social science and public health data showing the effectiveness of gun safety laws in order to uphold them, and instead must determine whether the regulation is within the historical tradition of this country’s firearms regulations. While we expect many gun safety laws will withstand this review, this new framework poses a long-term threat to other gun safety laws across the country—from assault weapon restrictions to prohibitions on gun access by domestic abuse offenders. Given the high lethality of America’s gun violence crisis, this new framework could ultimately lead to more increases in firearm violence.

Weakening of State Gun Laws

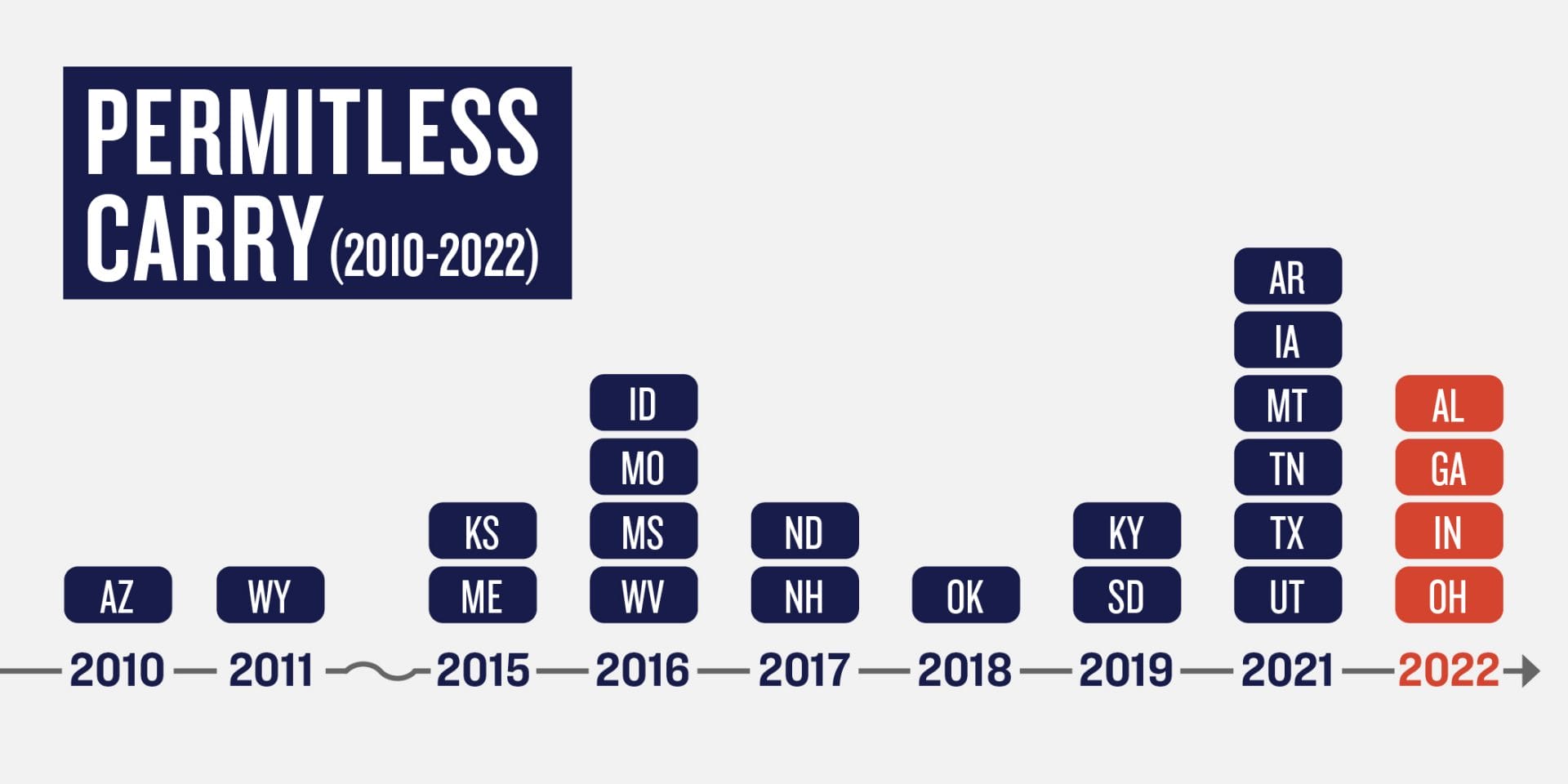

Although some states have responded to the surge in violence in recent years by passing critical gun safety measures, other states have expanded dangerous, reckless laws that endanger public safety. There is a strong body of research that suggests that as states pass these dangerous laws, including permitless carry and Stand Your Ground laws, gun deaths and injuries will dramatically increase.

With an explosion of permitless carry bills being enacted across the country in recent years, half the states now allow people to carry a concealed, loaded firearm in public with no permit. Six states—Arkansas, Iowa, Montana, Tennessee, Texas, and Utah—passed permitless carry laws in 2021, and another four states—Alabama, Indiana, Georgia, and Ohio—passed these laws in 2022.

Only one of the 25 permitless carry states requires a person to pass a background check or receive any safety training in order to buy a gun, and none of these states require people to take either of these steps in order to carry a gun. This means that the vast majority of permitless carry states take almost no steps to prevent people with serious histories of violence and dangerous behavior from acquiring and carrying hidden, loaded weapons in public.

As described in regards to the Supreme Court ruling, the data is abundantly clear that weaker concealed carry laws lead to higher rates of violent crime. A recently released study of permitless carry laws also suggests that this policy may increase shootings by police. Researchers found that states that adopted permitless carry laws experienced a 13% increase, on average, in combined fatal and nonfatal shootings of civilians by police, compared to what would have happened had states not adopted this policy.

On top of permitless carry laws however, states have also passed other dangerous policies. Arkansas, Ohio, and North Dakota passed Stand Your Ground laws in 2021. Studies suggest that Stand Your Ground laws are associated with an eight percent increase in both overall homicides and firearm homicides,48 as well as significant increases in firearm injuries resulting in emergency room visits and inpatient hospitalizations.49

When states weaken their own gun laws, it can not only impact gun violence in their state but also in surrounding states. In 2021, for example, Iowa repealed its permit-to-purchase law that required individuals to obtain a permit and background check when buying a handgun from an unlicensed seller. Evidence from other states that have repealed this policy would suggest that repealing this law will lead to increases in gun homicides and gun suicides,50 as well as increased gun trafficking to other states.51 Accordingly, we should expect these policy changes to lead to more gun violence in the coming years across a number of states.

There are numerous factors that will influence gun violence rates in the coming years. Our country has just passed policies that will save lives while also being given a decision that will undoubtedly cost lives. At this moment, it isn’t possible to predict the net result of these changes, particularly given the other dynamics that will both increase and decrease risk for gun violence. In the coming years, we must rely on researchers to parse the evidence and data and determine how these policies, in combination, have modified the risk for gun violence.

It is important to remember, however, that gun violence rates in the next few years need not only be determined by the policy changes that have already happened. Although the recent federal legislation was a critical first step in making communities safer, we know that there are a number of additional steps that need to be taken to fully address this crisis.

Policymakers must meet the risk of increasing gun violence in the coming years with bold action, passing laws like universal background checks and extreme risk laws so that people in all states can be protected by these measures.

JOIN THE FIGHT

Gun violence costs our nation 40,000 lives each year. We can’t sit back as politicians fail to act tragedy after tragedy. Giffords Law Center brings the fight to save lives to communities, statehouses, and courts across the country—will you stand with us?

- L.-C. Chien and M. Gakh, “The Lagged Effect of State Gun Laws on the Reduction of State–Level Firearm Homicide Mortality in the United States from 1999 to 2017,” Public Health 189 (2020): 73–80.[↩]

- See, e.g., Rocco Pallin et al., “Assessment of Extreme Risk Protection Order Use in California from 2016 to 2019,” JAMA Network Open 3, no. 6 (2020): e207735–e207735; Aaron J. Kivisto and Peter Lee Phalen, “Effects of Risk-based Firearm Seizure Laws in Connecticut and Indiana on suicide rates, 1981–2015,” Psychiatric Services 69, no. 8 (2018): 855–862; “The Department of Justice’s Semiannual Report on the Fix NICS Act,” US Department of Justice, July 2021, https://www.justice.gov/dag/page/file/1417981/download.[↩]

- Kelly Drane, “Surging Gun Violence: Where We Are, How We Got Here, and Where We Go Next,” Giffords Law Center, May 4, 2022, https://giffords.org/lawcenter/report/surging-gun-violence-where-we-are-how-we-got-here-and-where-we-go/.[↩]

- Id; See also, “A Devastating Toll: 2021 CDC Data Shows Record Number of Gun Deaths, Makes Clear the Need for Continued Action to Address Gun Violence in America,” Giffords Law Center, July 14, 2022, https://giffords.org/press-release/2022/07/2021-cdc-data-shows-record-number-of-gun-deaths/.[↩]

- Matthew Miller et al., “Household Firearm Ownership and Rates of Suicide Across the 50 United States,” Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 62, no. 4 (2007): 1029–1035; Matthew Miller et al., “The Association Between Changes in Household Firearm Ownership and Rates of Suicide in the United States, 1981–2002,” Injury Prevention 12, no. 3 (2006): 178–182; Lisa M. Hepburn and David Hemenway, “Firearm Availability and Homicide: A Review of the Literature,” Aggression and Violent behavior 9, no. 4 (2004): 417–440; Matthew Miller, David Hemenway, and Deborah Azrael, “State-level Homicide Victimization Rates in the US in Relation to Survey Measures of Household Firearm Ownership, 2001–2003,” Social Science & Medicine 64, no. 3 (2007): 656–664; Michael Siegel et al., “The Relationship Between Gun Ownership and Stranger and Nonstranger Firearm Homicide Rates in the United States, 1981–2010,” American Journal of Public Health 104, no. 10 (2014): 1912–1919.[↩]

- See, e.g., Bindu Kalesan et al., “Firearm Legislation and Firearm Mortality in the USA: a Cross-sectional, State-level Study,” The Lancet 387, no. 10030 (2016): 1847–1855.[↩]

- Jeffrey W. Swanson et al., “Implementation and Effectiveness of Connecticut’s Risk–based Gun Removal Law: Does it Prevent Suicides,” Law & Contemporary Problems 80, (2017): 179–208; Jeffrey W. Swanson et al., “Criminal Justice and Suicide Outcomes with Indiana’s Risk-Based Gun Seizure Law.” The Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law (2019).[↩]

- Aaron J. Kivisto and Peter Lee Phalen, “Effects of Risk-based Firearm Seizure Laws in Connecticut and Indiana on suicide rates, 1981–2015,” Psychiatric Services 69, no. 8 (2018): 855–862.[↩]

- Garen J. Wintemute, et al., “Extreme Risk Protection Orders Intended to Prevent Mass Shootings: a Case Series,” Annals of Internal Medicine (2019).[↩]

- April M. Zeoli et al., “Analysis of the Strength of Legal Firearms Restrictions for Perpetrators of Domestic Violence and Their Association with Intimate Partner Homicide,” American Journal of Epidemiology 187, no. 11 (2018); Carolina Díez et al., “State Intimate Partner Violence–related Firearm Laws and Intimate Partner Homicide Rates in the United States, 1991 to 2015,” Annals of Internal Medicine 167, no. 8 (2017): 536–543.[↩]

- April M. Zeoli et al., “Analysis of the Strength of Legal Firearms Restrictions for Perpetrators of Domestic Violence and Their Association with Intimate Partner Homicide,” American Journal of Epidemiology 187, no. 11 (2018).[↩]

- See, e.g., “Community Violence Intervention: What You Need to Know,” Giffords, June 2022, https://files.giffords.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Giffords-What-Is-CVI_2022.pdf.[↩]

- Sheyla A. Delgado et al., “The Effects of Cure Violence in the South Bronx and East New York, Brooklyn,” John Jay College of Criminal Justice, October 2017, https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1436&context=jj_pubs#:~:text=Cure%20Violence%20is%20a%20neighborhood,most%20vulnerable%20to%20gun%20violence.[↩]

- Paul M. Reaping et al., “State Firearm Laws, Gun Ownership, and K-12 School Shootings: Implications for School Safety,” Journal of School Violence 21, no. 2 (2022): 132–146.[↩]

- Joshua D. Brown and Amie J. Goodin, “Mass Casualty Shooting Venues, Types of Firearms, and Age of Perpetrators in the United States, 1982–2018,” American Journal of Public Health 108, no. 10 (2018): 1385–1387; Jaclyn Schildkraut, “Can Mass Shootings be Stopped? To Address the Problem, We Must Better Understand the Phenomenon,” Rockefeller Institute of Government and Regional Gun Violence Research Consortium, July 2021, https://rockinst.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Public-Mass-Shootings-Brief.pdf.[↩]

- Eighteen to 20 year olds commit 18% of gun homicides, despite comprising just four percent of the US population. Giffords Law Center analysis of FBI Supplementary Homicide Report (SHR) data, 2016–2020.[↩]

- Erin Renee Morgan et al., “Incarceration and Subsequent Risk of Suicide: A Statewide Cohort Study,” Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 52, no. 3 (2022) 467–477.[↩]

- Mona A. Wright, Garen J. Wintemute, and Frederick P. Rivara, “Effectiveness of Denial of Handgun Purchase to Persons Believed to be at High Risk for Firearm Violence,” American Journal of Public Health 89, no. 1 (1999): 88–90.[↩]

- Elinore J. Kaufman et al., “State Firearm Laws and Interstate Firearm Deaths from Homicide and Suicide in the United States: a Cross–sectional Analysis of Data by County,” JAMA Internal Medicine 178, no. 5 (2018): 692–700; Erik J. Olson et al., “American Firearm Homicides: The Impact of Your Neighbors,” Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 86, no. 5 (2019): 797–802.[↩]

- Sae Takada et al., “Firearm Laws and the Network of Firearm Movement Among US States,” BMC Public Health 21, no. 1 (2021): 1–11; David M. Hureau and Anthony A. Braga, “The Trade in Tools: The Market for Illicit Guns in High–Risk Networks,” Criminology 56, no. 3 (2018): 510–545.[↩]

- Frances Stokes Berry and William D. Berry, “Innovation and Diffusion Models in Policy Research,” in Theories of the Policy Process (Cambridge, MA: Westview Press, 2018): 223–260.[↩]

- Wendy J. Schiller and Kaitlin N. Sidorsky, “Federalism, Policy Diffusion, and Gender Equality: Explaining Variation in State Domestic Violence Firearm Laws 1990–2017,” State Politics & Policy Quarterly (2022): 1–23.[↩]

- Id.[↩]

- US Department of Justice, “Justice Department Announces New Rule to Modernize Firearm Definitions,” news release, April 11, 2022, https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-announces-new-rule-modernize-firearm-definitions.[↩]

- Brandi Hitt, “‘Ghost Guns’ Investigation: Law Enforcement Seeing Unserialized Firearms on Daily Basis in SoCal,” ABC 7, January 30, 2020, https://abc7.com/ghost-guns-california-gun-laws-kits/5893043/; Alain Stephens, “Ghost Guns Are Everywhere in California,” The Trace, May 17, 2019, https://www.thetrace.org/2019/05/ghost-gun-california-crime/.[↩]

- The White House, “FACT SHEET: President Biden Issues Call for State and Local Leaders to Dedicate More American Rescue Plan Funding to Make Our Communities Safer – And Deploy These Dollars Quickly,” news release, May 13, 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/05/13/fact-sheet-president-biden-issues-call-for-state-and-local-leaders-to-dedicate-more-american-rescue-plan-funding-to-make-our-communities-safer-and-deploy-these-dollars-quickly/.[↩]

- Anthony Braga et al., “Oakland Ceasefire Evaluation: Final Report to the City of Oakland,” May 2019, https://cao-94612.s3.amazonaws.com/documents/Oakland-Ceasefire-Evaluation-Final-Report-May-2019.pdf.[↩]

- Ellicott C. Matthay et al., “Firearm and Nonfirearm Violence After Operation Peacemaker Fellowship in Richmond, California, 1996–2016,” American Journal of Public Health 109, no. 11 (2019): 1605–1611.[↩]

- Anne C. Tremblay et al., “The City of Los Angeles Mayor’s Office of Gang Reduction and Youth Development (GRYD) Comprehensive Strategy,” GRYD Research & Evaluation Brief No. 1, LA GRYD, June 2020, https://www.juvenilejusticeresearch.com/sites/default/files/2020-08/GRYD%20Brief%201_GRYD%20Comprehensive%20Strategy_6.2020.pdf; Jeffrey P. Brantingham, George Tita, and Denise Herz, “The Impact of the City of Los Angeles Mayor’s Office of Gang Reduction and Youth Development (GRYD) Comprehensive Strategy on Crime in the City of Los Angeles,” Justice Evaluation Journal 4, no. 2 (2021): 217–236.[↩]

- Jason Corburn, Yael Nidam, and Amanda Fukutome-Lopez, “The Art and Science of Urban Gun Violence Reduction: Evidence from the Advance Peace Program in Sacramento, California,” Urban Science 6, no. 1 (2022).[↩]

- Jason Corburn and Amanda Fukutome, “Advance Peace Stockton 2018-20 Evaluation Report,” University of California Berkeley, Center for Global Healthy Cities, January 2021, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/591a33ba9de4bb62555cc445/t/600e4e99c7b03668060f1f7d/1611550368219/Advance+Peace+Stockton+Eval+Report+2021+FINAL.pdf.[↩]

- “Community Violence Intervention: What You Need to Know,” Giffords, June 2022, https://files.giffords.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Giffords-What-Is-CVI_2022.pdf.[↩]

- Kelly Drane, “Surging Gun Violence: Where We Are, How We Got Here, and Where We Go Next,” Giffords Law Center, May 4, 2022, https://giffords.org/lawcenter/report/surging-gun-violence-where-we-are-how-we-got-here-and-where-we-go/.[↩]

- Id; See also, Giffords, “A Devastating Toll: 2021 CDC Data Shows Record Number of Gun Deaths, Makes Clear the Need for Continued Action to Address Gun Violence in America,” news release, July 14, 2022, https://giffords.org/press-release/2022/07/2021-cdc-data-shows-record-number-of-gun-deaths/.[↩]

- Kelly Drane, “Surging Gun Violence: Where We Are, How We Got Here, and Where We Go Next,” Giffords Law Center, May 4, 2022, https://giffords.org/lawcenter/report/surging-gun-violence-where-we-are-how-we-got-here-and-where-we-go/.[↩]

- Id.[↩]

- Jeffrey M. Jones, “In U.S., Black Confidence in Police Recovers From 2020 Low,” Gallup, July 14, 2021, https://news.gallup.com/poll/352304/black-confidence-police-recovers-2020-low.aspx.[↩]

- “Violence Reduction Dashboard,” City of Chicago, last accessed July 19, 2022, https://www.chicago.gov/city/en/sites/vrd/home.html.[↩]

- “Citywide Crime Statistics,” New York City Police Department, last accessed July 19, 2022, https://www1.nyc.gov/site/nypd/stats/crime-statistics/citywide-crime-stats.page.[↩]

- “Shootings,” Analyze Boston, City of Boston, last accessed July 19, 2022, https://data.boston.gov/dataset/shootings.[↩]

- John J. Donohue, Abhay Aneja, and Kyle D. Weber, “Right to Carry Laws and Violent Crime: A Comprehensive Assessment Using Panel Data and a State Level Synthetic Control Analysis,” Journal of Empirical Legal Studies 16, no. 2 (2019): 198–247.[↩]

- Michael Siegel et al., “Easiness of Legal Access to Concealed Firearm Permits and Homicide Rates in the United States,” American Journal of Public Health 107, no. 12 (2017): 1923–1929.[↩]

- John J. Donohue et al., “More Guns, More Unintended Consequences: The Effects of Right-to-Carry on Criminal Behavior and Policing in US Cities,” National Bureau of Economic Research, no. w30190 (2022).[↩]

- Id.[↩]

- Id.[↩]

- Id.[↩]

- Id.[↩]

- Michelle Degli Esposti et al., “Analysis of ‘Stand Your Ground’ Self-defense Laws and Statewide Rates of Homicides and Firearm Homicides,” JAMA Network Open 5, no. 2 (2022): e220077–e220077; Alexa R. Yakubovich et al., “Effects of Laws Expanding Civilian Rights to Use Deadly Force in Self-defense on Violence and Crime: a Systematic Review,” American Journal of Public Health 111, no. 4 (2021): e1–e14.Michelle Degli Esposti et al., “Analysis of ‘Stand Your Ground’ Self-defense Laws and Statewide Rates of Homicides and Firearm Homicides,” JAMA Network Open 5, no. 2 (2022): e220077–e220077; Alexa R. Yakubovich et al., “Effects of Laws Expanding Civilian Rights to Use Deadly Force in Self-defense on Violence and Crime: a Systematic Review,” American Journal of Public Health 111, no. 4 (2021): e1–e14.[↩]

- Chandler McClellan and Erdal Tekin, “Stand Your Ground Laws, Homicides, and Injuries,” Journal of Human Resources 52, no. 3 (2017): 621–653.[↩]

- Alexander D. McCourt et al., “Purchaser Licensing, Point-of-Sale Background Check Laws, and Firearm Homicide and Suicide in 4 US States, 1985–2017,” American Journal of Public Health 110, no. 10 (2020): 1546–1552.[↩]

- D.W. Webster et al., “Preventing the Diversion of Guns to Criminals through Effective Firearm Sales Laws,” in Reducing Gun Violence in America: Informing Policy with Evidence and Analysis, eds. Daniel W. Webster and Jon S. Vernick (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013), 109–122.[↩]