The Role of Guns in Rising Political Violence

In recent years, political violence has become more frequent, more brazen, and more dangerous.

Those that serve our democracy, from the vice president and speaker of the House to local government officials, have been increasingly bullied, threatened, and attacked simply for doing their jobs.

Importantly, this rise in political violence has coincided with an increase in firearm access, driven by spikes in gun purchasing since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. These factors each heighten the risk for violence individually, but together, these trends could represent a catastrophic threat to our democracy and the safety of the American public. In fact, recent data suggests that Americans are increasingly willing to tolerate or justify using violence against elected officials—which could spell disaster when coupled with increased firearm access.

To understand how guns are being used in threats against government officials, Giffords Law Center reviewed more than 150 federal indictments for individuals charged with threatening federal elected officials. This review shows that more often than not, firearms are invoked or used in the most serious threats of political violence. Alarmingly, female lawmakers and lawmakers of color were disproportionately represented among threatened individuals, and a majority of threats against people in these groups involved firearms.

Addressing the role that guns play in political violence is a fundamental step to protecting those who serve our democracy—and protecting those who serve our government is paramount to preserving our democracy itself.

MEDIA REQUESTS

Our experts can speak to the full spectrum of gun violence prevention issues. Have a question? Email us at media@giffords.org.

Contact

In the early morning hours of October 28, 2022, an assailant entered the home of Speaker Nancy Pelosi, hoping to kidnap her and break her kneecaps because he was sick of what he described as the “level of lies” coming from Washington. While Speaker Pelosi was not home, the intruder violently attacked her husband, breaking his skull with a hammer. After the suspect was arrested, he told police that he also had other targets, including a local professor and several prominent state and federal politicians.

Less than two years earlier, hundreds of insurrectionists breached police barricades, broke windows, and stole property at the US Capitol in the January 6 attack. Threats were made to hang then-Vice President Mike Pence and harm other elected officials. Rioters assaulted approximately 1,000 law enforcement officers,1 and hundreds sustained injuries.2 At least seven people lost their lives in connection with the attack, including a Capitol police officer who was assailed by the mob.3 Rioters brought enough bullets into the building to shoot every member of Congress at least five times.4

How America’s Gun Laws Fuel Armed Hate

May 23, 2022

These attacks come on the heels of growing acts of political violence. In the weeks before the January 6 attack, rioters breached the Oregon statehouse building and confronted law enforcement with an ax and pepper spray to protest the US presidential election results.5 Just months earlier, the FBI arrested 13 men who had plotted to kidnap the governor of Michigan and use violence to overthrow the state government.

In January 2020, tens of thousands of armed protesters convened at the Virginia State Capitol in an attempt to scare legislators away from enacting lifesaving gun safety legislation.6 Hundreds of armed protesters also staged demonstrations at state capitol buildings in Idaho,7 Kentucky,8 Michigan,9 Ohio,10 Pennsylvania,11 and Wisconsin12 to intimidate lawmakers who supported measures to slow the spread of COVID-19.

Government officials at every level have faced increased threats and risks to their safety in recent years. A recent poll of members of Congress found that three in four respondents had received a death threat since 2020, with such threats aimed at both Democrats and Republicans.13 Capitol Police announced that investigations of threats against members of Congress rose from 3,939 in 2017 to 9,625 in 2021—a spike of almost 150%.14

Government workers and local elected officials have been harassed, attacked, and threatened at increasing rates since the start of the pandemic. In fact, a survey by the National League of Cities found that 81% of local officials said they had personally experienced harassment, threats, or physical violence during this time period.15 An analysis of more than 3,000 incidents where local officials were threatened found that gun violence was overrepresented among these threats, with threats of death and gun violence more than twice as common as any other form of threat.16

These threats have particularly targeted government workers and elected officials in the election, public health, and education space.17 A survey conducted in the summer of 2021 found that a quarter of Americans believe that threatening public health officials because of COVID-19-related business closures was justified.18 In September 2021, the National School Boards Association sent a letter to President Biden asking for his administration’s help in curtailing an uptick in violent threats against school board members.19 A survey conducted by the Brennan Center found that one in six election officials have experienced threats because of their job, and 77% say that they feel these threats have increased in recent years.20 In fact, the US Department of Justice reports that there have been more than 1,000 “hostile” contacts made with election officials over the course of a one-year investigation.21

Given the increasing numbers of violent threats facing public officials, it is perhaps unsurprising that numerous recent polls suggest a growing tolerance, and in some cases a willingness, to use violence to achieve political ends. A January 2021 survey found that more than one in three (36%) Americans and nearly three in five (56%) Republicans agree with the statement that “the traditional American way of life is disappearing so fast that we may have to use force to save it.”22 Similarly, just under a third of Americans completely or somewhat agree that “if elected leaders will not protect America, the people must do it themselves, even if it requires taking violent actions.”23

Other polls have also shown a growing tolerance for political violence:

- A November 2021 survey found that one in five Americans—including nearly one in three Republicans—agree that “because things have gotten so far off track, true American patriots may have to resort to violence in order to save our country.”24

- A poll conducted between December 2021 and January 2022 found that a quarter of Americans thought violence was either “definitely” or “probably” justifiable against the government, with one in 10 Americans saying that such violence was justifiable “right now.”25

- A February 2021 survey found that roughly equal numbers of Democrats and Republicans (11% and 12%) said that assassinations carried out by their party would be at least “a little bit” justified.26

- A May-June 2022 survey found that while nearly 80% of Americans think political violence “in general” is never justified, 20% think it is sometimes, usually, or always justified.27

- A September 2022 survey found that 17% of Americans somewhat or strongly agree that political violence against those they disagreed with was acceptable.28

- An October 2022 poll similarly found that some registered voters believe that taking up arms or a civil war is necessary to fix our democracy.29

One November 2021 poll questioned respondents about support for violence across multiple dimensions, from sending threatening messages online to using force against government officials. This study found that the number of Americans who supported the use of physical force or violence to advance political goals was much smaller—just four to five percent.30 However, even this more specific and narrowly focused poll would suggest that more than 10 million American adults endorse political violence in some situations.31

A 2022 poll similarly found that a sizable minority of Americans were willing to engage in political violence, including lethal violence. Eight percent of Americans endorsed at least some willingness to threaten or intimidate a person, seven percent are at least somewhat willing to injure a person, and five percent are at least somewhat willing to kill a person to advance political objectives.32

Importantly, polls that have asked questions about tolerance for political violence over time have seen that support for such violence has risen recently. For example, a December 2021 poll from the University Of Maryland’s Center for Democracy and Civic Engagement found that 34% of respondents think that it is “ever justified for citizens to take violent action against the government.”33 Polls that asked the same question in October 2015, January 2011, and April 2010 found that just 23%, 16%, and 16% of respondents, respectively, believed that violence against the government could ever be justified.34

Some evidence suggests that these increases may be particularly sharp, with substantial growth over just a period of months. Forty-four percent of Republicans and 41% of Democrats said in September 2020 that there would be at least “a little” justification for violence if the other party’s nominee wins the election—up from June 2020, when 35% of Republicans and 37% of Democrats agreed with this statement.35 The percent of people who said it was at least “a little” justified for their side “to use violence in advancing political goals” also grew from the June 2020 to September 2020 poll, up three percent for Democrats and six percent for Republicans.36

The fact that tolerance for political violence is rising reflects a self-perpetuating vicious cycle: early research suggests that violent events, such as the January 6 attack, can actually increase public approval of future political violence.37 Evidence also seems to suggest that individuals are more supportive of using violence themselves if they believe that people with differing political views are likely to use violence.38 These research findings were echoed in a June 2021 FBI report, which speculated that “the current [post-January 6] environment likely will continue to act as a catalyst for some to begin accepting the legitimacy of violent action.”39

Polling data supports this early research and shows that Americans are increasingly tolerant of political violence if another party engages in violence first. For example, October 2020 polling suggests that 23% of Americans condone violence in response to an opposing party’s electoral victory, but support for using violence skyrockets up to 40% if such violence would be used in retaliation.40

Critically, beliefs do not always translate into behaviors. Although these polls show that a substantial and growing number of Americans could tolerate or justify political violence, the majority of Americans still reject these ideals. And polls show waning support for “completely” endorsing political violence.41

Nevertheless, there is evidence to suggest that these attitudes may create risk for real-world violence. One study conducted via surveys before and after the 2020 election found that just 1.5% of all respondents had ever hit, pushed, or grabbed people in a conflict over politics.42 However, nine percent of respondents who believed that violence to achieve political ends was at least sometimes justified had engaged in this kind of physical confrontation.43 While more research is needed, this study could indicate an increased risk of violent actions in correlation with increases in more tolerant attitudes towards political violence.

If tolerance of political violence provides the fuel that imperils our democracy, easy access to guns could spark a conflagration. In recent years, gun sales have soared to unprecedented levels. In March 2020, around the onset of the coronavirus pandemic in the US, gun sales increased by 83% compared to the same month the prior year.44 This initial spike can likely be attributed to new uncertainties about safety and decreased social disorder prompted by the pandemic.

However, gun sales remained high throughout 2020 and through 2021, with purchasing spikes during widespread racial justice protests in the summer of 2020, after the 2020 election, after the January 6 attack and inauguration of President Biden, and after the string of mass shootings in Atlanta, Georgia, and Boulder, Colorado, in the spring of 2021. Overall, Americans purchased an estimated 22 million guns in 2020—an increase of nearly 65% over the previous year’s sales.45 Another 20 million guns were purchased in 2021.46

The number of guns sold in 2020 and 2021 broke many previous sales records. In fact, since the National Instant Check System (NICS) became operational in 1998, the nine weeks with the most background checks processed through this system occurred during 2020 or 2021.47 Seven of the 10 days with the most background checks processed happened during these same two years.48

Researchers estimate that nearly three million more US adults purchased firearms in 2020 than in 2019. Importantly, however, survey data suggests that a number of gun purchasers in 2020 were people who did not previously own firearms. In fact, one survey estimated that 3.8 million people who purchased guns in 2020 were first-time gun buyers.49 These increased purchases and the increase in new gun owners in 2020 led to an estimated 9.3 million people becoming newly exposed to household firearms, including three million children.50 In other words, millions of people who did not previously have access to household guns now do after these purchasing spikes.

These increased purchases and newly exposed Americans are cause for concern: a substantial body of research shows that higher levels of household gun ownership correspond with higher rates of gun deaths and injuries. Additionally, the presence of a gun in the home triples the risk for suicide,51 doubles the risk for homicide,52 and increases the lethality of domestic violence situations.53

However, it is possible that these new gun purchases could also increase the risk for and lethality of political violence. In recent years, firearms have become the “weapon of choice” for violent extremists, with these weapons used in a growing share of extremist-involved killings.54 A leaked report from federal law enforcement agencies similarly described how extremists are particularly interested in acquiring firearms and indicated that privately made and untraceable firearms, also known as ghost guns, are a particularly attractive source of weapons for these individuals.55

The proliferation of guns in civilian hands in recent years at the very least could make these weapons more easily accessible for those who wish to cause harm to others or those who harbor extremist ideals. However, it is also possible that some of the increased gun purchasing may have been driven, in part, by individuals already predisposed to some views popular among extremist groups. One study in Texas, for example, found that people who purchased a gun in the early months of the pandemic were more likely than non-purchasers to believe the threat of COVID-19 was overstated.56 Importantly, this downplaying of the threat of COVID-19 has been associated in other studies with far-right extremist views.57

Another survey, conducted between March 2020 and October 2021, similarly suggests that “pandemic gun buyers represent an extreme group in terms of political and psychological characteristics including several risk-factors for violence and self-harm.”58 Specifically, this study found that compared to non-gun owners and pre-pandemic gun owners, people who purchased guns during the pandemic were more likely to hold extremist beliefs related to QAnon, Christian nationalism, former President Trump, vaccines, and COVID-19.59 Pandemic purchasers were also more likely than non-gun owners and longstanding gun owners to display a number of characteristics that suggest increased risk for violence, including suicidality, depression, anxiety, substance use, antisocial personality, a history of intimate partner violence, a desire for power, a belief in a dangerous world, low agreeableness, and low conscientiousness.60

Anecdotal evidence similarly suggests that extremists may have stocked up on guns in recent years. For example, one leader of a far-right extremist group indicted for seditious conspiracy and other charges for crimes related to the breach of the US Capitol on January 6 was found to have spent more than $20,000 on guns and other tactical equipment in the days leading up to the Capitol attack,61 illustrating how extremist individuals specifically seek out firearms and other weapons.

Alarmingly, one 2022 survey found support for the idea that individuals with extremist leanings are willing to use firearms to advance political objectives. Survey results show that 18.5% of Americans believe it is at least somewhat likely they will be armed with a gun “in a situation where…force or violence is justified to advance an important political objective.”62 Those who identify as strong Republicans were more than twice as likely as those who identify as strong Democrats to endorse this statement.63 Approximately four percent of Americans believe it is at least somewhat likely they will shoot someone with a gun to advance a political objective.64

Taken together, the above data suggests an increasingly armed society as well as one which is increasingly tolerant of or willing to engage in violence to achieve political ends. In an effort to better understand the frequency at which firearm-involved threats of political violence are happening, Giffords Law Center reviewed federal court indictments for cases where people threatened federal elected officials filed between January 2016 and September 2022.

2021 CDC Data Shows Record Number of Gun Deaths

Jul 14, 2022

Cases were identified through a systematic review of news reports and press releases from the US Department of Justice. Importantly, this review of federal prosecutions did not include a number of cases where threats against federal law makers were prosecuted in state courts. This review also does not encompass a number of threats made against unelected federal officials, or people elected at the state and local levels.

In total, 153 indictments were identified. For each case, we coded information about the invocation of firearms within the threat, as well as other pertinent characteristics, based on information included within the case file, particularly the criminal complaint, indictment, and sentencing documents, when applicable.

Among reviewed cases, the vast majority of defendants (96%) were male. Defendants ranged in age from 19 to 77, with an average age of 44, and came from 42 states.

Of the indictments that provided specific details about the threats made to elected officials,65 more than half (54%) invoked the use of firearms. Many of these threats involved individuals threatening to shoot elected officials. In a number of cases, individuals also expressed that they could easily acquire a firearm within their threats to legislators. These cases involved a wide variety of threats, including:

- A Florida man left a voicemail for Speaker Nancy Pelosi threatening to “come a long, long way to rattle her head with bullets” and to cut her head off “jihadist-style.” The man also left threatening messages for Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Cook County prosecutor Kim Foxx.

- A Utah man made threats to at least 10 members of Congress because of his anger over abortion policies, immigration, and anti-Trump rhetoric. These threats repeatedly invoked firearms and the Second Amendment, with him telling one representative that he would “be the first to blow their [sic] head off—that’s not a threat, that’s a promise” and telling another representative he would “use his Second Amendment right to blow the [representative’s] head off.”

- A New York man left a message for Senator Raphael Warnock saying that “three cars of armed patriots [were] heading into DC from New York” with their “guns cleaned and loaded . . . just waiting for the word.”

- An Ohio man threatened to assault and murder a US representative and a member of the representative’s family. In his threat, he stated that the 2017 congressional baseball game shooting was just “the tip of the iceberg.”

- A Minnesota man threatened a Republican senator, saying he “couldn’t wait” to kill him. In his threats, the man also noted that Republicans’ opposition to gun safety laws made it easy for a self-described “volatile person” like himself to acquire a gun to “carry out [his] nefarious goals.”

- A Georgia man made multiple racist threats to a Black senator, including threats to kill him and asking whether he needed to “just do what [the Charleston Church shooter] did.”

Of threats targeting members of Congress, more than half (52%) were directed at Democratic legislators. Thirty-eight percent were directed at Republican legislators. A few (7%) threats were directed at a combination of Democratic and Republican legislators. The political affiliation of the threatened party could not be determined in a small number (4%) of cases. While threats against Democratic Congress members generally were made in opposition to Democratic Party positions or dislike of Democrats, threats against Republican Congress members included both threats criticizing Republican policies and threats toward Republican members who did not support President Trump or his policies. A relatively similar number of threats against Democratic legislators and Republican legislators involved threats of gun violence (53% and 59%, respectively).

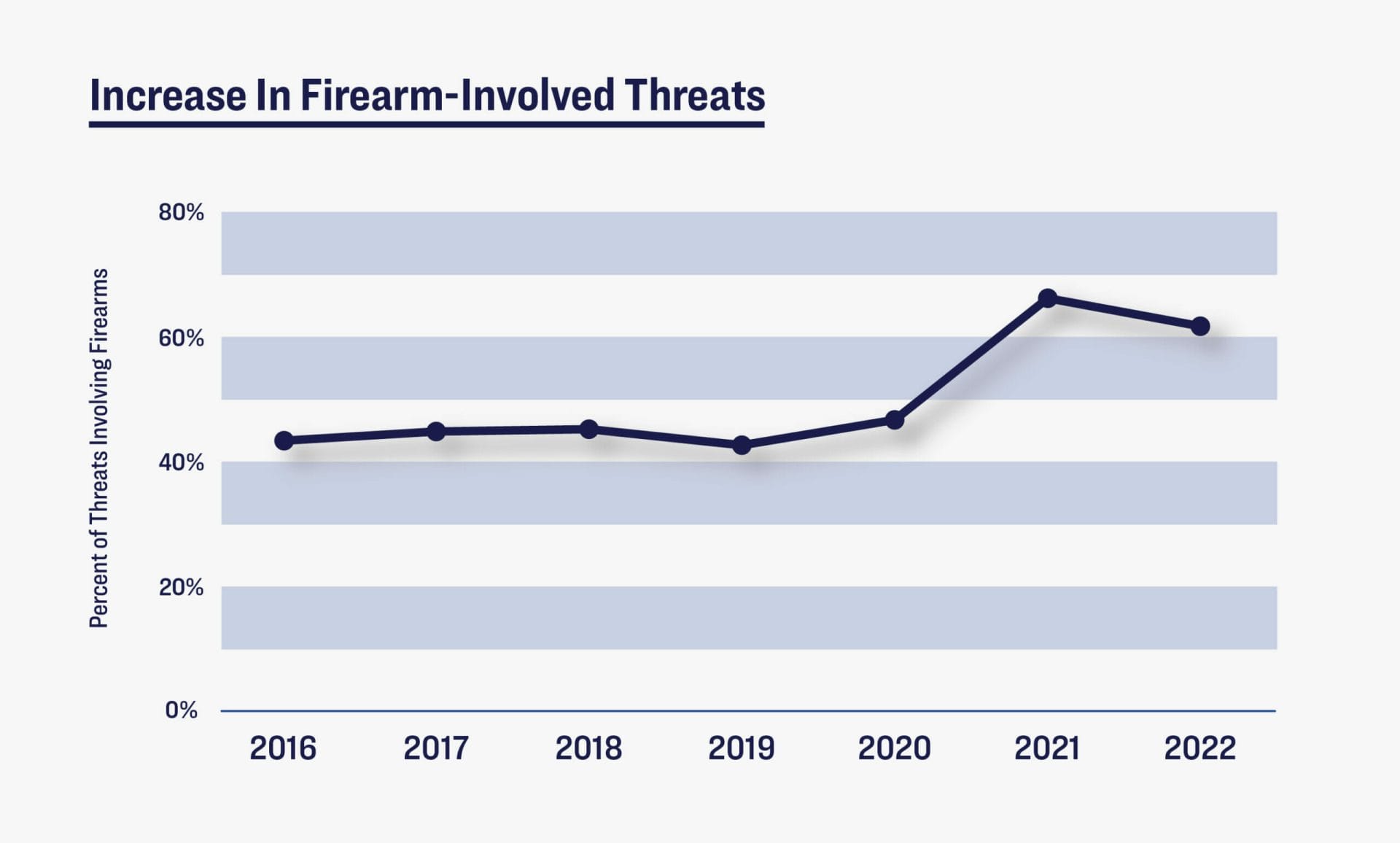

Of particular note, our analysis suggests that the proportion of threats to federal elected officials involving firearms has risen in recent years. From 2016 to 2020, an average of 45% of threats invoked firearms. From January 2021 to October 2022, 63% of threats invoked firearms, suggesting that in recent years, threats to lawmakers were more likely to involve threats of firearm violence.

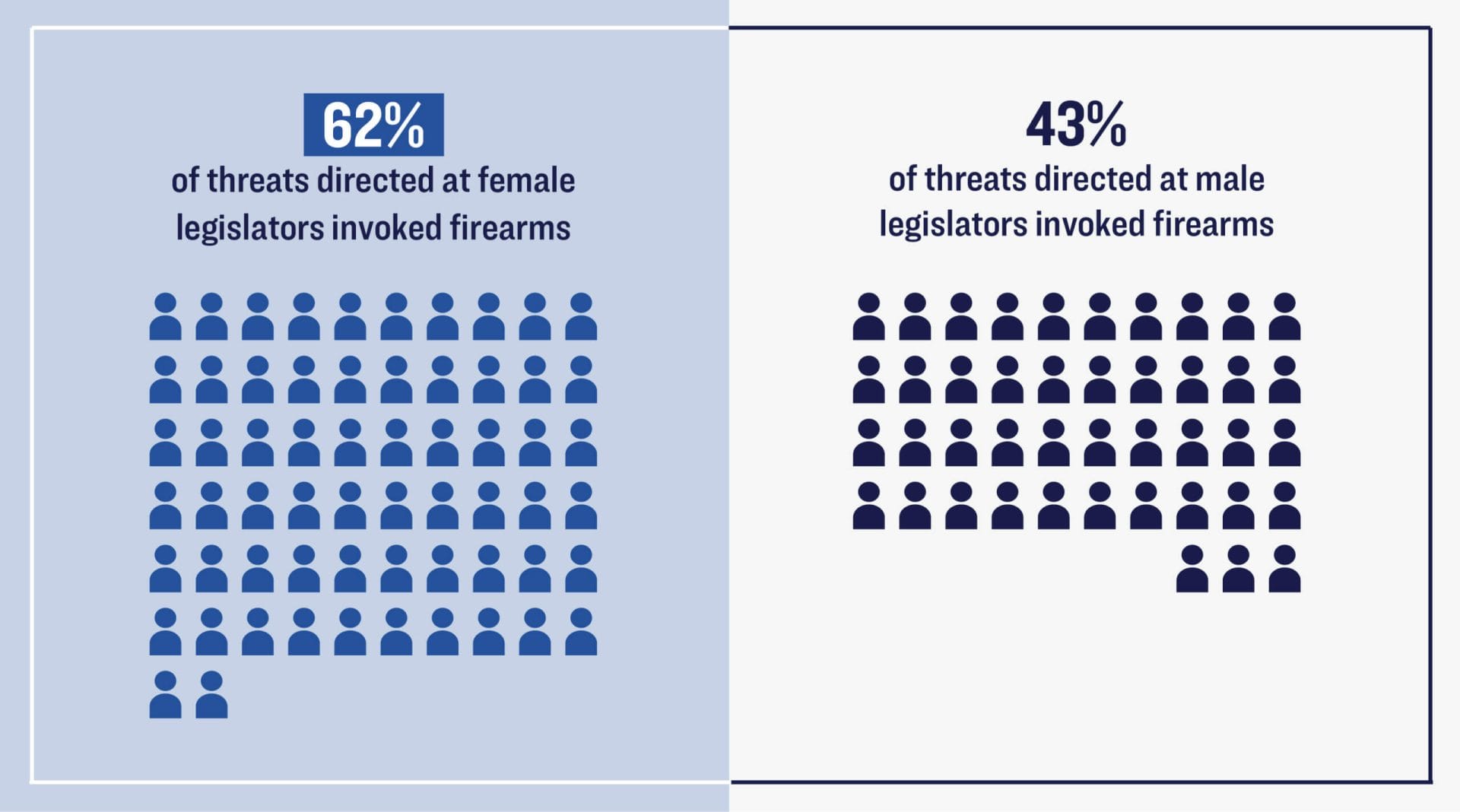

The cases collected also suggest that female legislators and legislators of color were disproportionately targeted. For example, 48% of indictments involving threats to federal legislators included threats directed to female members of Congress, despite the fact that women held between only 19% and 27% of seats in Congress from 2016 and 2022.66 Alarmingly, threats directed at female legislators were more likely to involve firearms: while 43% of threats directed at male legislators involved mention of firearms, 62% of threats directed at female legislators invoked firearms.

Legislators of color67 were also disproportionately likely to experience threats of intimidation of violence. Although people of color held just 18% to 25% of congressional seats between 2016 and 2022,68 38% of indictments involved threats made to legislators of color. Fifty-three percent of threats to legislators of color involved threats of gun violence.

IN THE COURTS

Time and again, gun safety laws have been proven constitutional. Our attorneys defend lifesaving gun laws and take on the gun lobby in courts around the country, all the way up to the Supreme Court.

Learn More

The data on tolerance for political violence and our review of cases of threatened political violence suggest a grim picture—and perhaps an even grimmer one to come. But importantly, while polls show an increased tolerance for political violence, Americans are also increasingly embracing the kinds of policies that can help strengthen our democracy and prevent political violence.69

We cannot curb extremism in our country—and protect our democracy—without a robust strengthening of our nation’s gun laws. Recent events would suggest that strong gun laws can play a critical role in preventing violent extremism. Testimony in the January 6 hearings and prosecutions of insurrectionists alleges that the Oath Keepers, an extremist group, stockpiled firearms in a Virginia hotel room but did not carry those guns on the day of the riot so as not to run afoul of Washington DC’s strong gun laws.70 Scholars have speculated that had gun laws in Washington DC been weaker, there could have been even more violence during the Capitol attack.71

State and federal governments must enact policies to keep guns away from sensitive areas and take steps to ensure that individuals who have espoused dangerous extremist views are not able to buy and possess firearms. In a recent report, Giffords Law Center made several recommendations for how states can better ensure that all Americans can exercise their democratic rights without the threat of violence. These policies include:

- Prohibiting all guns in government buildings, state and local government meetings, and other places where elected officials regularly congregate or where people exercise their democratic rights

- Prohibiting open carry, particularly at permitted protests and demonstrations

- Repealing state preemption statutes and allowing local governments to pass laws about where and when guns can be carried

Additionally, our gun laws must be strengthened to ensure that people who are legally ineligible to have firearms cannot easily acquire them, which will help keep guns away from some individuals who have previously espoused extremist ideas. These policies must include:

- Passing universal background check laws, which provide an important foundation to keep firearms from people who want to do harm

- Enacting and implementing extreme risk laws and other firearm-prohibiting protective orders to help ensure that firearms can be removed from individuals who espouse dangerous intentions to cause harm

- Fully implementing the federal ghost gun rule and enacting state laws to regulate the existing stock of untraceable firearms

Giffords is all too familiar with the costs of political violence. Our founder, former Congresswoman Gabby Giffords, and 18 others were shot during a constituent event on January 8, 2011. In the 12 years since this attack, violence against political officials has only escalated, and woefully little has been done to address the threat of guns to our democracy.

As our report demonstrates, individuals are attempting to use firearms to elevate their views and voices above those of others with growing frequency. But democracy cannot function if those who serve it are constrained by the threat of armed violence. Inherent to the idea of democracy is the premise that all people—not just a select group of individuals—have a say in their government. It is imperative that policymakers at every level of government take steps to address our concurrent crises of gun violence and a democracy under threat.

SPOTLIGHT

GUNS & DEMOCRACY

The use of guns to intimidate and threaten voters, elected officials, and peaceful demonstrators poses a serious threat to our democracy. We’ve gathered resources on the deadly connection between guns and extremism, and how to stop it.

Read More- Alexander Mallin, “‘Approximately 1,000’ Assaults on Law Enforcement Occurred During Capitol Attack, DOJ Review Finds,” ABC News, September 2, 2021, https://abcnews.go.com/US/approximately-1000-assaults-law-enforcement-occurred-capitol-attack/story?id=79793226.[↩]

- Tom Jackman, “Police Union Says 140 Officers Injured in Capitol Riot,” Washington Post, January 27, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/public-safety/police-union-says-140-officers-injured-in-capitol-riot/2021/01/27/60743642-60e2-11eb-9430-e7c77b5b0297_story.html.[↩]

- Chris Cameron, “These Are the People Who Died in Connection With the Capitol Riot,” New York Times, January 5, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/05/us/politics/jan-6-capitol-deaths.html.[↩]

- Justin Wagner, “Enough Ammunition to Shoot Every Member of the House and Senate,” Newsweek, January 15, 2021, https://www.newsweek.com/heavily-armed-insurrectionists-capitol-1561974. See also, Harper Neidig, “Police Seized Alarming Number of Weapons on Capitol Rioters, Court Documents Show,” The Hill, January 16, 2021, https://thehill.com/regulation/court-battles/534329-police-seized-alarming-number-of-weapons-on-capitol-rioters-court.[↩]

- Mike Baker, “In a Different Capitol Siege, Republicans in Oregon Call for Accountability,” New York Times, June 8, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/08/us/oregon-capitol-protest-nearman.html.[↩]

- Bill Chappell, “Richmond Gun Rally: Thousands Of Gun Owners Converge On Virginia Capitol On MLK Day,” NPR, January 20, 2020, https://www.npr.org/2020/01/20/797895183/richmond-gun-rally-thousands-of-gun-owners-converge-on-virginia-capitol-on-mlk-d.[↩]

- Paulina Firozi, “Anti-government Activist Ammon Bundy Arrested After Maskless Protesters Storm Idaho Capitol,” Washington Post, August 25, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2020/08/25/ammon-bundy-idaho/.[↩]

- Sarah Ladd, “Beshear Hanged in Effigy as Second Amendment Supporters Rally at Capitol Before Memorial Day,” Louisville Courier Journal, May 24, 2020, https://www.courier-journal.com/story/news/politics/2020/05/24/second-amendment-supporters-protest-covid-19-restrictions-capitol/5250571002/.[↩]

- Lois Beckett, “Armed Protesters Demonstrate Against Covid-19 Lockdown at Michigan Capitol,” The Guardian, April 30, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/apr/30/michigan-protests-coronavirus-lockdown-armed-capitol.[↩]

- “Armed Protesters Gathered Outside Statehouse Demanding DeWine Reopen Ohio,” Fox 8 Cleveland, May 1, 2020, https://fox8.com/news/coronavirus/armed-protesters-gathered-outside-statehouse-demanding-dewine-reopen-ohio/.[↩]

- Cynthia Fernandez, “Hundreds Gather at Capitol in Harrisburg for Anti-shutdown Rally Calling to ‘Reopen’ Pennsylvania,” Spotlight PA, April 20, 2020, https://www.spotlightpa.org/news/2020/04/pennsylvania-anti-shutdown-rally-harrisburg/.[↩]

- Reid J. Epstein and Kay Nolan, “A Few Thousand Protest Stay-at-Home Order at Wisconsin State Capitol,” New York Times, April 24, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/24/us/politics/coronavirus-protests-madison-wisconsin.html.[↩]

- Jim Saska, “‘Rise in Violent Rhetoric’: Lawmakers in Both Parties Report Spike in Death Threats,” Roll Call, January 20, 2022, https://www.rollcall.com/2022/01/20/rise-in-violent-rhetoric-lawmakers-in-both-parties-report-spike-in-death-threats/.[↩]

- Nicholas Wu, “Threats Against Members of Congress Doubled in 2021, Capitol Police Say,” Politico, May 7, 2021, https://www.politico.com/news/2021/05/07/threats-against-congress-doubled-2021-485753.[↩]

- Clarence E. Anthony et al., “On the Frontlines of Today’s Cities: Trauma, Challenges, and Solutions,” National League of Cities, November 2021, https://www.nlc.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/On-the-Frontlines-of-Todays-Cities-1.pdf.[↩]

- Joel Day, Aleena Khan, and Michael Loadenthal, “Threats and Harassment Against Local Officials Dataset,” Princeton Bridging Data Initiative, October 20, 2022, https://bridgingdivides.princeton.edu/sites/g/files/toruqf246/files/documents/Threats%20and%20Harassment%20Report.pdf.[↩]

- Id.[↩]

- Michelle M. Mello, Jeremy A. Greene, and Joshua M. Sharfstein, “Attacks on Public Health Officials During COVID-19,” JAMA 324, no. 8 (2020): 741–742.[↩]

- Anya Kamenetz, “School Boards are Asking for Federal Help as they Face Threats and Violence,” NPR, September 30, 2021, https://www.npr.org/sections/back-to-school-live-updates/2021/09/30/1041870027/school-boards-federal-help-threats-violence.[↩]

- Ruby Edlin and Turquoise Baker, “Poll of Local Election Officials Finds Safety Fears for Colleagues — and Themselves,” Brennan Center for Justice, March 10, 2022, https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/analysis-opinion/poll-local-election-officials-finds-safety-fears-colleagues-and.[↩]

- “Readout of Election Threats Task Force Briefing with Election Officials and Workers,” US Department of Justice, August 1, 2022, https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/readout-election-threats-task-force-briefing-election-officials-and-workers.[↩]

- Daniel A. Cox, “After the Ballots Are Counted: Conspiracies, Political Violence, and American Exceptionalism,” Survey Center on American Life, February 11, 2021, https://www.americansurveycenter.org/research/after-the-ballots-are-counted-conspiracies-political-violence-and-american-exceptionalism/.[↩]

- Id.[↩]

- “Competing Visions of America: An Evolving Identity or a Culture Under Attack? Findings from the 2021 American Values Survey,” PRRI, November 1, 2021, https://www.prri.org/research/competing-visions-of-america-an-evolving-identity-or-a-culture-under-attack/.[↩]

- Alauna C. Safarpour et al., “The COVID States Project: A 50-State COVID-19 Survey, Report #80: Americans’’ Views On Violence Against the Government,” The COVID States Project, January 2022, https://osf.io/753cb/.[↩]

- Blake Hounshell and Leah Askarinam, “How Many Americans Support Political Violence?,” New York Times, January 5, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/05/us/politics/americans-political-violence-capitol-riot.html.[↩]

- Garen J. Wintemute et al., “Views of American Democracy and Society and Support for Political Violence: First Report from a Nationwide Population-representative Survey,” MedRxiv (2022).[↩]

- “Core Political Presidential Approval Tracker and

- Biden’s Speech on Democracy,” Reuters/Ipsos, September 2022, https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/ct/news/documents/2022-09/Ipsos%20Poll%20Presidential%20Approval%20Tracker%20and%20Biden%27s%20Speech%2009%2008%202022.pdf.[↩]

- “Topline Results for the October 2022 Times/Siena Poll of Registered Voters,” New York Times, October 18, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2022/10/18/upshot/times-siena-poll-toplines.html.[↩]

- “Tempered Expectations and Hardened Divisions a Year Into the Biden Presidency,” Brightline Watch, November 2021, http://brightlinewatch.org/tempered-expectations-and-hardened-divisions-a-year-into-the-biden-presidency/.[↩]

- Calculated by taking four percent of the US Census estimate of 2021 adult population: 260,850,584*.04=10,434,023. Id.; “Quick Facts,” US Census Bureau, last accessed March 10, 2022, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045221.[↩]

- Garen J. Wintemute et al., “Views of American Democracy and Society and Support for Political Violence: First Report from a Nationwide Population-representative Survey,” MedRxiv (2022).[↩]

- “Dec. 17-19, 2021, Washington Post-University of Maryland Poll,” Washington Post, January 1, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/context/dec-17-19-2021-washington-post-university-of-maryland-poll/2960c330-4bbd-4b3a-af9d-72de946d7281/.[↩]

- Id.[↩]

- Larry Diamond, Lee Drutman, Tod Lindberg, Nathan P. Kalmoe, and Lilliana Mason, “Americans Increasingly Believe Violence is Justified if the Other Side Wins,” Politico, October 1, 2020, https://www.politico.com/news/magazine/2020/10/01/political-violence-424157.[↩]

- Id.[↩]

- Nathan P. Kalmoe and Lilliana Mason, “Partisan Terrorism Effects on Violent Partisan Attitudes: A Natural Experiment during the 2018 U.S. Election Campaign,” Cooperative Congressional Election Study, last accessed March 8, 2022, https://www.dropbox.com/s/c92444mx4l0ln09/Terrorism%20Effects%20on%20Violent%20Partisan%20Attitudes.pptx?dl=0.[↩]

- Mernyk, Joseph, Sophia Pink, James Druckman, and Robb Willer, “Correcting Inaccurate Metaperceptions Reduces Americans’ Support for Partisan Violence,” OSF Preprints, February 2022, https://osf.io/8ftsx/.[↩]

- “Adherence to QAnon Conspiracy Theory by Some Domestic Violent Extremists,” Federal Bureau of Investigation, June 4, 2021, https://s3.documentcloud.org/documents/20889411/adherence-to-qanon-conspiracy-theory-by-some-domestic-violent-extremists4.pdf.[↩]

- “American Democracy on the Eve of the 2020 Election,” Brightline Watch, October 2020, http://brightlinewatch.org/american-democracy-on-the-eve-of-the-2020-election/.[↩]

- Daniel A. Cox, “After the Ballots Are Counted: Conspiracies, Political Violence, and American Exceptionalism,” Survey Center on American Life, February 11, 2021, https://www.americansurveycenter.org/research/after-the-ballots-are-counted-conspiracies-political-violence-and-american-exceptionalism/.[↩]

- Lilliana Mason and Nathan P. Kalmoe, “What You Need to Know About How Many Americans Condone Political Violence — and Why,” Washington Post, January 11, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2021/01/11/what-you-need-know-about-how-many-americans-condone-political-violence-why/.[↩]

- Id.[↩]

- Based on Giffords Law Center calculations of adjusted NICS data. “NICS Firearm Background Checks: Month/Year,” Federal Bureau of Investigation, last accessed April 1, 2021, https://www.fbi.gov/file-repository/nics_firearm_checks_-_month_year.pdf/view.[↩]

- Id.[↩]

- Id.[↩]

- Federal Bureau of Investigation, “NICS Firearm Checks: Top 10 Highest Days/Weeks, November 30, 1998–January 31, 2022,” last accessed December 22, 2022, https://www.fbi.gov/file-repository/nics_firearm_checks_top_10_highest_days_weeks.pdf/view.[↩]

- Id.[↩]

- Matthew Miller, Wilson Zhang, and Deborah Azrael, “Firearm Purchasing During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Results From the 2021 National Firearms Survey,” Annals of Internal Medicine (2021).[↩]

- Id.[↩]

- Andrew Anglemyer, Tara Horvath, and George Rutherford, “The Accessibility of Firearms and Risk for Suicide and Homicide Victimization among Household Members: a Systematic Review and Meta–analysis,” Annals of Internal Medicine 160, no. 2 (2014): 101–110.[↩]

- Id.[↩]

- J.C. Campbell et al., “Risk Factors for Femicide in Abusive Relationships: Results from a Multisite Case Control Study,” American Journal of Public Health 93, no.7 (2003): 1089–1097.[↩]

- Mark Pitcavage, “Firearms Increasingly Weapon of Choice in Extremist-Related Killings,” Anti-Defamation League, April 13, 2016, https://www.adl.org/blog/firearms-increasingly-weapon-of-choice-in-extremist-related-killings.[↩]

- “First Responder Awareness of Privately Made Firearms May Prevent Illicit Activities,” Joint Terrorism Assessment Team, June 22, 2021, https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/21037846-pmf-report; Stephen Stock and Jeremy Carroll, “Ghost Guns Sought by Violent Extremists, Tied to Thousands of Potential Crimes, Feds Warn,” NBC Bay Area, August 7, 2021, https://www.nbcbayarea.com/investigations/ghost-guns-sought-by-violent-extremists-tied-to-thousands-of-potential-crimes-feds-warn/2624959/.[↩]

- Renee M. Johnson et al., “Differences in Beliefs about COVID-19 by Gun Ownership: a Cross–sectional Survey of Texas Adults,” BMJ Open 11, no. 11 (2021).[↩]

- Ciarán O’Connor, “The Conspiracy Consortium: Examining Discussions of COVID-19 Among Right-Wing Extremist Telegram Channels,” Institute for Strategic Dialogue, December 2021, https://www.isdglobal.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/The-Conspiracy-Consortium.pdf; “Member States Concerned by the Growing and Increasingly Transnational Threat of Extreme Right-Wing Terrorism,” CTED Trends Alert, United Nations Security Council Counter-Terrorism Committee Executive Directorate, July 2020, https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/ctc/sites/www.un.org.securitycouncil.ctc/files/files/documents/2021/Jan/cted_trends_alert_extreme_right-wing_terrorism_july.pdf; Matt Motta, Dominik Stecula, and Christina Farhart, “How Right–Leaning Media Coverage of COVID-19 Facilitated the Spread of Misinformation in the Early Stages of the Pandemic in the US,” Canadian Journal of Political Science 53, no. 2 (2020): 335–342.[↩]

- Brian M. Hicks et al., “Who Bought a Gun During the COVID-19 Pandemic in the United States?: Associations with QAnon Beliefs, Right-wing Political Attitudes, Intimate Partner Violence, Antisocial Behavior, Suicidality, and Mental Health and Substance Use Problems,” PsyArXiv (2022).[↩]

- Id.[↩]

- Id.[↩]

- Sergio Olmos, “Guns, Ammo … Even a Boat: How Oath Keepers Plotted an Armed Coup,” The Guardian, January 14, 2022, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2022/jan/14/oath-keepers-leader-charges-armed-plot-us-capitol-attack.[↩]

- Garen J. Wintemute et al., “Views of American Democracy and Society and Support for Political Violence: First Report from a Nationwide Population-representative Survey,” MedRxiv (2022).[↩]

- Garen J. Wintemute et al., “Party Affiliation, Political Ideology, Views of American Democracy and Society, and Support for Political Violence: Findings from a Nationwide Population-Representative Survey,” SocArXiv (2022).[↩]

- Garen J. Wintemute et al., “Views of American Democracy and Society and Support for Political Violence: First Report from a Nationwide Population-representative Survey,” MedRxiv (2022).[↩]

- For a small number of these cases, the information in the case file did not allow us to determine whether or not a threat involved a firearm, often because the criminal complaint describing the threats made had been sealed. These cases were excluded from our analysis of firearm use.[↩]

- Jennifer E. Manning, “Membership of the 114th Congress: A Profile,” Congressional Research Service, December 2016, https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/R43869.pdf; Jennifer E. Manning, “Membership of the 115th Congress: A Profile,” Congressional Research Service, December 2018, https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/R44762.pdf; Jennifer E. Manning, “Membership of the 116th Congress: A Profile,” Congressional Research Service, December 2020, https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/R45583.pdf; Jennifer E. Manning, “Membership of the 117th Congress: A Profile,” Congressional Research Service, December 2022, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R46705.[↩]

- Legislators of Color include legislators who identify as Black, Hispanic/Latino, Asian/Pacific Islander, American Indian/Alaska Native. Legislators of color were largely identified through rosters maintained by the Office of the House Historian and the Clerk of the House’s Office of Art and Archives, available at https://history.house.gov/Exhibitions-and-Publications/. American Indian/Alaska Native legislators were identified through news media reporting on AI/AN representation in Congress. “Black-American Members by Congress,” History, Art & Archives United States House of Representatives, last accessed December 22, 2022, https://history.house.gov/Exhibitions-and-Publications/BAIC/Historical-Data/Black-American-Representatives-and-Senators-by-Congress/; “Hispanic-American Representatives, Senators, Delegates, and Resident Commissioners by Congress,” History, Art & Archives United States House of Representatives, last accessed December 22, 2022, https://history.house.gov/Exhibitions-and-Publications/HAIC/Historical-Data/Hispanic-American-Representatives,-Senators,-Delegates,-and-Resident-Commissioners-by-Congress/; “Asian and Pacific Islander American Representatives, Senators, Delegates, and Resident Commissioners by Congress,” History, Art & Archives United States House of Representatives, last accessed December 22, 2022, https://history.house.gov/Exhibitions-and-Publications/APA/Historical-Data/By-Congress/. See also, Caitlin O’Kane, “A Record-breaking 6 Native Candidates Were Elected to Congress on Tuesday,” CBS News, November 6, 2020, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/six-native-americans-elected-to-congress-record-breaking/.[↩]

- Jennifer E. Manning, “Membership of the 114th Congress: A Profile,” Congressional Research Service, December 2016, https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/R43869.pdf; Jennifer E. Manning, “Membership of the 115th Congress: A Profile,” Congressional Research Service, December 2018, https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/R44762.pdf; Jennifer E. Manning, “Membership of the 116th Congress: A Profile,” Congressional Research Service, December 2020, https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/R45583.pdf; Jennifer E. Manning, “Membership of the 117th Congress: A Profile,” Congressional Research Service, December 2022, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R46705.[↩]

- See, e.g., “American Attitudes toward Extremist Threats: A Survey Following the Events at the U.S. Capitol,” Anti-Defamation League, January 1, 2021, https://www.adl.org/resources/report/american-attitudes-toward-extremist-threats-survey-following-events-us-capitol; Alexandra Filindra, “Americans do not Want Guns at Protests, This Research Shows,” Washington Post, November 21, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2021/11/21/americans-do-not-want-guns-protests-this-research-shows/.[↩]

- Ryan J. Reilly and Daniel Barnes, “Oath Keeper Testifies About Massive Gun Pile Stashed in Hotel on the Eve of Jan. 6,” NBC News, October 12, 2022, https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/justice-department/oath-keeper-testifies-massive-gun-pile-stashed-hotel-eve-jan-6-rcna51749.[↩]

- Jake Charles, “Strict Gun Laws Likely Saved Lives During the Capitol Insurrection,” Duke Center for Firearms Law, January 27, 2021, https://firearmslaw.duke.edu/2021/01/strict-gun-laws-likely-saved-lives-during-the-capitol-insurrection/.[↩]