How America’s Gun Laws Fuel Armed Hate

On March 15, 2021, Giffords Law Center first released this report examining the rise of hate-fueled extremism in the United States. The very next day, six Asian women and two other individuals were shot and killed at three different spas in the Atlanta area in targeted acts of hate.

Just over a year later, on May 11, 2022—during Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) Heritage Month—three Asian women were shot at a hair salon in Dallas, Texas, a shooting which investigators think may be connected to other recent shootings at Asian-owned businesses in the area. Hate crimes against AAPI individuals have skyrocketed since 2020, when former President Trump began espousing rhetoric that Asian people caused the virus.

Just a few days after the shooting in Dallas, on May 14, an 18-year-old white man radicalized by far-right extremism drove several hours to a predominately Black neighborhood to commit a bigoted act of domestic terrorism. Thirteen people—11 of whom were Black— were shot while grocery shopping. Of those 11, 10 died at the scene.

Prior to the shooting, the killer published a screed claiming that “critical race theory”—a recent right-wing talking point that has come to generally encompass teaching about race in school—is part of a Jewish plot and a reason to justify mass killings of Jews. The shooter, who obtained his guns legally and modified at least one of them into an illegal assault weapon, live streamed the massacre.

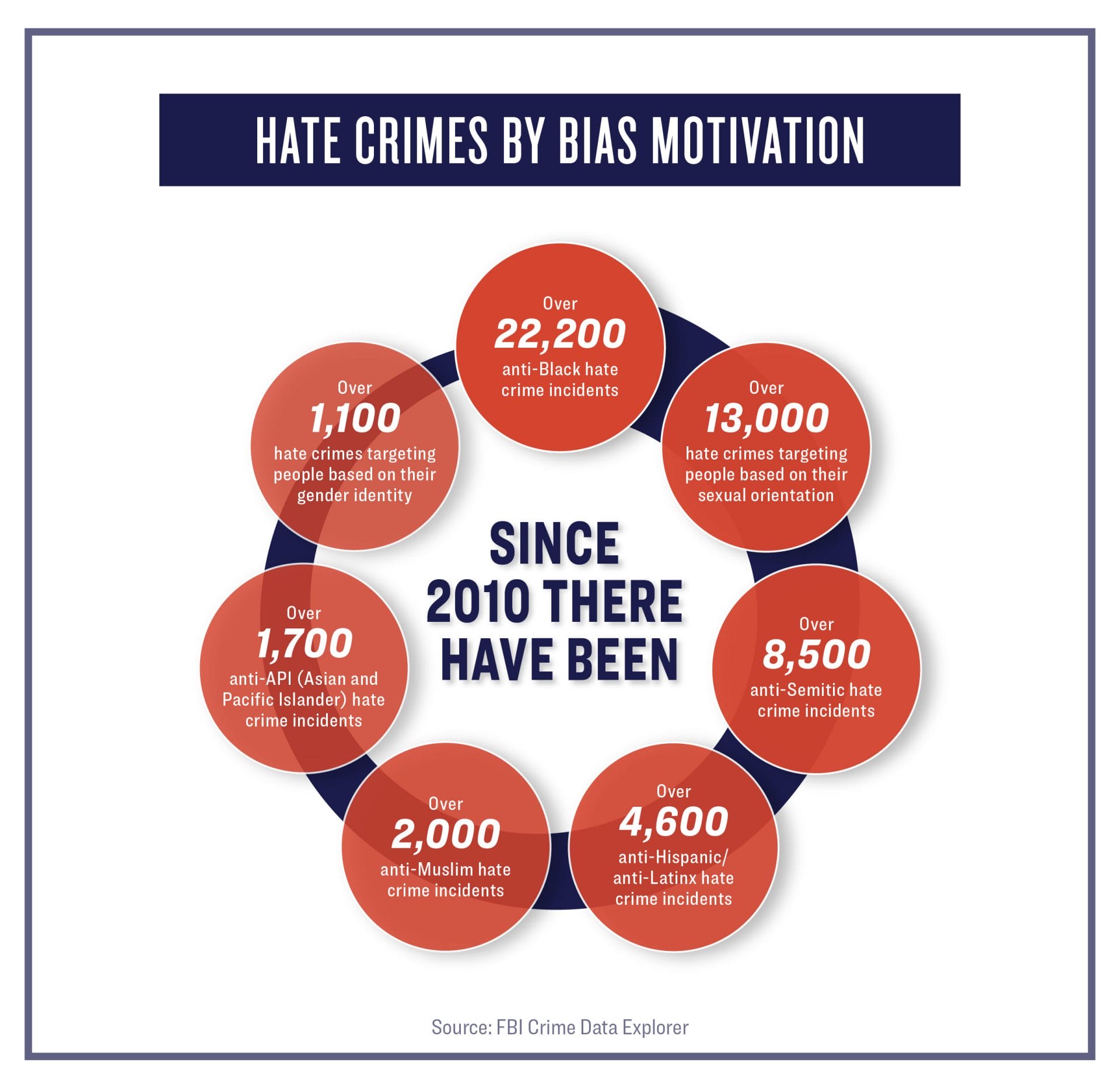

These shootings are but a few numerous high-profile shootings targeting racial, social, sexual, and religious minorities in the United States over the past few years. In fact, in 2021, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) released new data indicating that hate crimes in the US had reached their highest level in 12 years due mainly to spikes in violence against Black and Asian Americans.

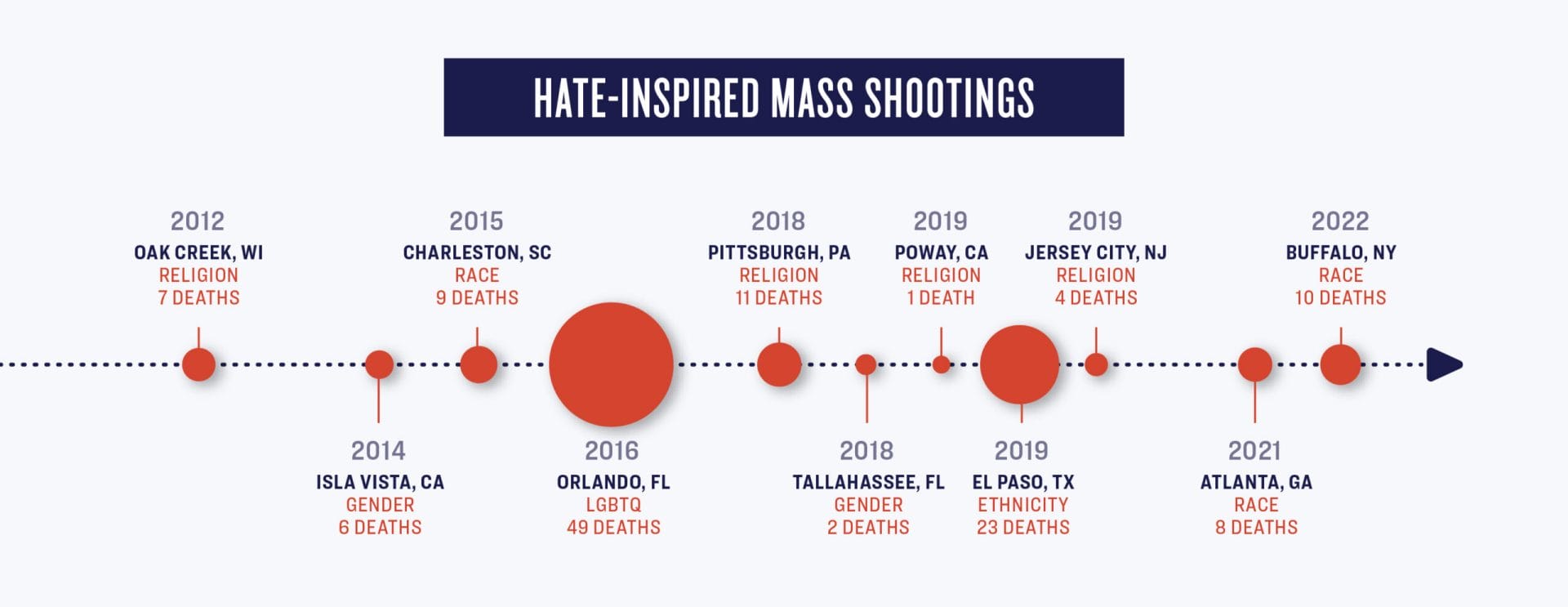

Like the shootings at the Walmart in El Paso, Texas; the Sikh Temple in Oak Creek, Wisconsin; the Tree of Life and Chabad Synagogues in Pittsburgh and Poway, California; Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina; and Pulse Nightclub in Orlando, Florida; the shootings in Dallas and Buffalo are the result of an escalating problem of armed hate, one that is growing larger each minute that federal and state legislators fail to address it.

Since we issued this call to action a year ago, there has not been enough action in the states—and no movement at all with federal legislation—towards preventing hate crimes with firearms. This must change and it must change now, before any more blood is shed.

Introduction

In recent years, extremist groups have become emboldened to expand beyond their private meetings, chat rooms, and message boards, recruiting new members through mainstream social media and gathering openly in public. This upswell of hateful ideology has also been accompanied by an escalation of public intimidation with firearms.

In 2015, a crowd of heavily armed demonstrators congregated in front of a mosque in Arizona, raising security fears for worshippers. In 2017, hundreds of white supremacists and neo-Nazis from across the country—many armed with semiautomatic rifles and handguns—converged on Charlottesville, Virginia, to protest the removal of a confederate statue. One woman was killed and 19 others were injured when a white supremacist rammed his car into a crowd of counter-protesters. Another counter-protester was beaten by a group of white supremacists and self-proclaimed “militia” members.

Disarm Hate Laws in All 50 States

In response to the rising tide of hate and the increase in hate-motivated violence, the FBI has elevated “racially motivated violent extremism” to be a top level priority threat, singling out white supremacy as a major driver of these attacks.1

Following the January 6, 2021, insurrection at the United States Capitol, the Department of Homeland Security warned that “domestic violent extremists” like the El Paso shooter may be emboldened by the breach of the Capitol building to commit further violence.2 America’s dangerously weak gun safety laws make it far too easy for people fueled by violent and hateful ideologies to intimidate, harm, and murder others.3

Too often, guns are the tools of violent hate and extremism, facilitating attacks that sow fear throughout entire communities. This report analyzes the impact and growing threat armed and violent hate crimes pose to American society, explains how our firearm laws are failing to adequately protect vulnerable communities from armed hate, and outlines ways in which lawmakers can strengthen our gun safety laws to respond to these threats. Giffords recommends that states and the federal government enact the following policies to protect all Americans against armed hate:

- Universal background checks to ensure that people purchasing firearms are eligible to possess them

- Military-style weapon and large-capacity magazine regulations that more thoroughly regulate civilian access to military-style weapons

- Extreme risk protection order laws, which allow for the temporary removal of firearms from people found by a court to pose an imminent risk of serious violence

- Laws that prohibit guns on government property and at civic events such as protests, demonstrations, meetings of legislative bodies, and elections

- “Disarm Hate” laws which prohibit firearm access for people who have been convicted of misdemeanor hate crimes which involve the use, or threatened use, of violence or deadly weapons

The report is primarily focused on the under-discussed potential of the latter three policies as approaches to protecting against armed hate. Additionally, this report’s linked appendix contains the most comprehensive 50-state analysis to date detailing access to guns by violent hate crime offenders.

MEDIA REQUESTS

Our experts can speak to the full spectrum of gun violence prevention issues. Have a question? Email us at media@giffords.org.

Contact

Hate Crimes Overview

The FBI defines a hate crime as “a criminal offense against a person or property motivated in whole or in part by an offender’s bias against a race, religion, disability, sexual orientation, ethnicity, gender, or gender identity.”4 Under federal law, prosecutors may charge people with hate crimes for offenses including assault, murder, arson, and vandalism, as well as threats or conspiracy to commit these offenses, when the offense is motivated by hate.

Not all acts of hate are hate crimes—hate crimes only occur when the act taken is a criminal offense. For example, a person handing out flyers promoting white supremacist ideology has not committed a crime. However, if a person motivated by the ideology contained in the flyer threatens or attacks a person because they are not white, that act could be charged as a hate crime. Depending on the state, hate crimes can also be prosecuted at the state level, though many state laws have less expansive definitions of what constitutes a hate crime than federal law.

Crimes motivated by bias are treated differently than crimes without bias motivations because their impact tends to be wider reaching than other crimes. Hate crimes, even when directed at an individual, victimize entire communities, and violent hate crimes tend to cause more psychological distress to victims than other violent crimes.5 In many cases, these crimes are intended to instill fear in members of the protected group. For example, the shootings at synagogues in Pittsburgh and Poway resulted in members of the Jewish community across the country fearing for their safety.6 Similarly, the shooting at Pulse nightclub made people more afraid to gather in LGBT spaces.7

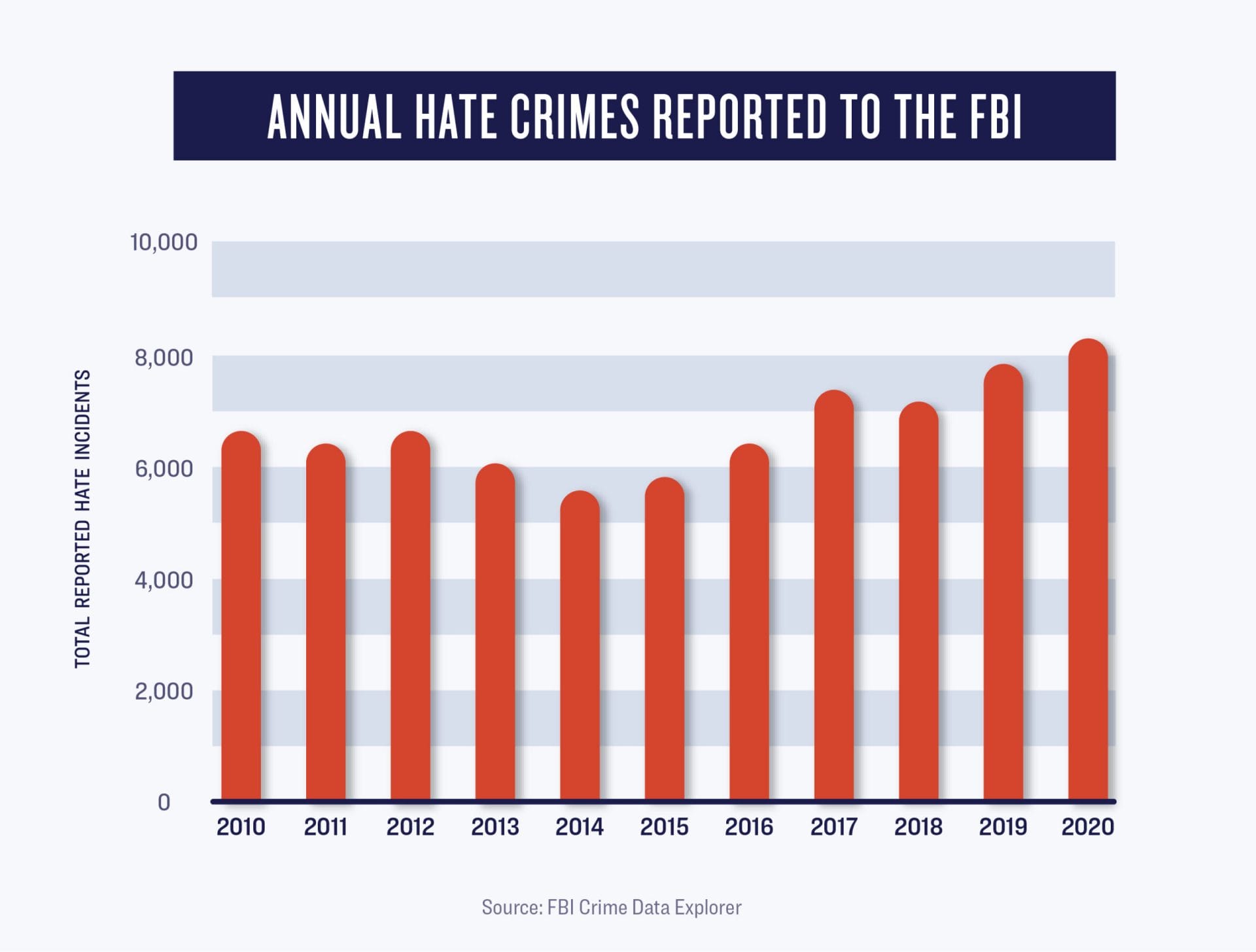

Hate crimes are shockingly common in the US, and FBI data indicates that this threat is fast increasing. The FBI began tracking hate crime incidents as part of its Uniform Crime Reports (UCR) in 1991. Other than brief spikes in 2001 and between 2006 and 2008, hate crimes were generally on the decline between 1996 and 2014.8

That trend seems to have reversed itself beginning in 2015, rising from 5,599 incidents reported in 2014 to 8,263 in 2020, with an alarming 48% increase in incidents reported over that time period.9 In 2020, police departments reported more than 22 hate crimes per day, on average.10

This number is likely an extreme undercount. The Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) also collects data on hate crimes as part of its National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS). In 2019 NCVS data suggests that 305,390 people experienced hate crime victimizations—42 times as many hate crime victimizations per year as reported by the FBI.11

That’s one hate crime every one minutes and 43 seconds.

Several factors play into the large discrepancy between these two sources. The FBI’s UCR data is aggregated from reports sent to the FBI from law enforcement agencies who voluntarily participate in this data collection program,12 while the BJS’s NCVS data is collected by conducting interviews with a nationally representative sample of 240,000 people about their experiences of nonfatal crime victimization over the last year. BJS then uses the results from the survey to estimate the total number of incidents in the country.13

A major factor in the gap in incident counts is that the NCVS data include incidents that were never reported to police. From 2015 to 2019, only 57% of violent hate crime victimizations and 29% of nonviolent hate crime victimizations were reported to law enforcement.14

Hate crimes are shockingly common in the US, and FBI data indicates that this threat is fast increasing.

Over the past two years, as a result of the scapegoating of Asian Americans by government officials in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a reported increase in xenophobia and bigotry against the Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) community.15 In too many cases, this hostile atmosphere has escalated into violence. From 2019 to 2020, the FBI documented a 73% increase in anti-Asian hate crimes—significantly higher than the 13% increase in overall hate crimes over this same period.

Data from police departments and community-based surveys have also shed light on these troubling increases. For example, the Center for Hate and Extremism examined police department data from 18 large cities across the US, finding that while hate crimes overall declined 6% from 2019 to 2020 among this sample, hate crimes targeting Asians rose 145%.16 Additionally, 16% of Asian American and 14% of Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islanders reported experiencing a hate crime or incident from January 2021 through March 2022—proportions which suggest that approximately three million AAPI adults have experienced a hate incident in just a fourteen month period.17

But the rise in hate extends beyond the Asian American community. From 2019 to 2020, large increases in hate crimes were also seen against religious groups, particularly Sikhs, who experienced a 65% increase.18 People of multiple races and Black people also saw a sharp spike, 61% and 46%, respectively.19 Increases in hate crimes based on gender identity also rose over this time period, with a 43% increase in hate crimes against gender non-conforming people and a 40% increase in anti-transgender hate crimes.20

In light of the recent increases in hate-fueled violence, and following the attacks in Pittsburgh and El Paso, in February of 2020 the FBI elevated “racially motivated violent extremism” to be a top level priority threat—the same priority level as ISIS.21 In a 2020 statement before the Senate Homeland Security Committee, FBI Director Christopher Wray said that violent extremists motivated by racial or religious hatred make up a significant portion of the FBI’s domestic terrorism investigations, and that the majority of those attacks are motivated by violent white supremacist ideologies.22

To help address the threat posed by white supremacist terrorism, in June of 2019 the FBI established the Domestic Terrorism-Hate Crimes Fusion Cell, which is tasked with coordinating investigations between the domestic terrorism and hate crime divisions.23 But to truly confront this challenge head on, we must address deadly loopholes in our federal gun laws that allow individuals convicted of violent hate crimes to purchase and possess guns.

HERE TO HELP

Interested in partnering with us to draft, enact, or implement lifesaving gun safety legislation in your community? Our attorneys provide free assistance to lawmakers, public officials, and advocates working toward solutions to the gun violence crisis.

CONTACT US

Guns Laws & Hate Crimes

Federal law makes it far too easy for people who have committed hate crimes to access firearms. In more than half of the states, an individual can buy an unlimited number of military-style weapons from private sellers without a background check and have thousands of rounds of ammunition delivered directly to their house, no questions asked. Though not every gun safety law could have stopped every massacre, foundational gun safety policies like universal background checks, restrictions on magazine size, and extreme risk protection order laws will help protect vulnerable communities from the devastating consequences of violent hate.

One particularly dangerous loophole in federal law allows thousands of people legally prohibited from possessing firearms to purchase them each year before their background checks are completed. In 2015, nine African American worshipers were murdered by a white supremacist during a Bible study at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church. Though the shooter was prohibited from purchasing guns, he was able to buy one from a federally licensed firearms dealer because of a loophole that allows a gun sale to continue if a background check has not finished processing after three days. This loophole allows thousands of ineligible purchasers to purchase firearms from federally licensed dealers each year.24

Even when a background check is required and conducted promptly, people convicted of violent hate crime misdemeanors are still eligible to purchase firearms in 28 states.25 Thirty-one states have no extreme risk law in place to remove firearms from individuals found to pose a serious and imminent threat to public safety. And most states allow people to openly carry firearms in public spaces, even at public protests and demonstrations where firearms can be used to suppress free speech, assembly, worship, and other rights.

Guns are a powerful tool of intimidation, and even the implied presence of a firearm when combined with a threat can induce fear. For example, an Oregon man was sentenced to 15 months in federal prison for terrorizing members of a Catholic church, at one point leaving a threatening note and ammunition.26

Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics National Crime Victimization Survey

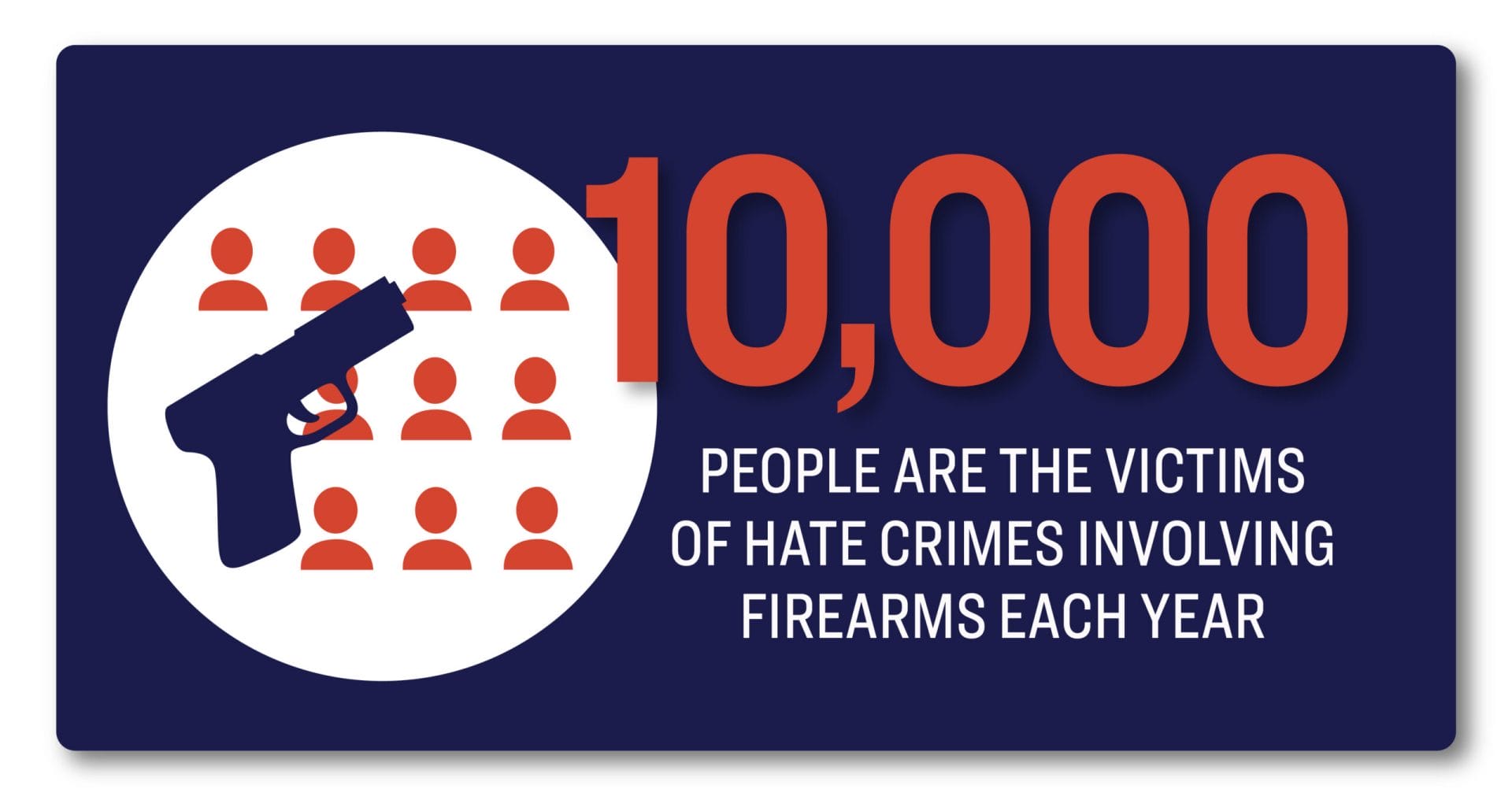

Though the vast majority of hate crimes do not involve firearms, NCVS data indicates that over 10,300 people are victims of hate crimes involving firearms per year.27 People who commit hate crimes, particularly those who commit violent hate crimes, are much more likely to commit repeat acts of violence. A study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association found that people who had previously been convicted of a violent misdemeanor were nine times more likely to be charged with another violent offense after purchasing a handgun, compared to people with no criminal history.28

Research has also shown that people who have been convicted of violent hate crimes are likely to continue or escalate their conduct. In their book Hate Crimes Revisited: America’s War on Those Who are Different, hate crime researchers Jack Levin and Jack McDevitt found that “individuals who commit hate crimes tend to escalate their conduct in order to ensure their message is received by the targeted individual or community.”29

People convicted of violent hate crime misdemeanors are still eligible to purchase firearms in 28 states.

They describe this trajectory of escalating violence in the context of “defensive hate crimes”—hate crimes committed by people who believe that they are defending something from outsiders or intruders, be it their neighborhood, their way of life, their country, or their religion.30

A similar extreme level of violence is present in crimes committed by those Levin and McDevitt call “mission offenders”—people who consider themselves crusaders for a cause and see themselves as waging a war against members of one or more protected groups. Offenders in this category tend to be involved in hate groups or to be heavily influenced by hate group ideology. Crimes committed by offenders in this category include the Oklahoma City bombing and the Charleston church shooting.

America is not currently doing enough to limit access to deadly weapons to people on hateful and violent trajectories. Examples abound of white supremacists, members of hate groups, and other extremists using firearms to intimidate, threaten, and attack members of vulnerable groups and ideological or political opponents. The particular dangers posed by members of these groups having ready access to firearms are discussed below.

Hate Groups & Armed Extremists

Hate groups encourage their members to adopt violent ideologies and bond over shared animosity toward members of protected groups. Researchers have found that membership in a hate group may increase the likelihood that a person becomes violent, because it puts that person in an environment that encourages violent behavior and dehumanizes potential victims of violence.31

Examples of the tragic consequences of armed hate are not hard to find. In 2009, members of an anti-immigrant, border-patrolling paramilitary group called the Minutemen American Defense Militia ambushed a Latino family in their home in an Arizona border town, killing Raul J. Flores and his nine-year-old daughter Brisenia and injuring his wife, Gina Gonzalez.32 The militia members falsely believed that Raul was involved in the drug trade and were planning to steal drugs and money from him to finance their border patrols.33

An investigation by FRONTLINE and ProPublica found that the American neo-Nazi group Atomwaffen,34 which has been linked to five known murders,35 holds “hate camps” to teach members how to use firearms and instruct them in tactics for guerilla warfare.36 Investigations by the Guardian and Vice found evidence that another white supremacist group, the Base, has organized similar “hate camps” throughout the United States.37 Members of this group were arrested for plotting to kill a couple whom they believed to be leaders in antifa,38 as well as for firearms violations in the days leading up to a gun rights rally in Richmond, Virginia.39 Both of these hate groups advocate for hate-based violence, with Atomwaffen calling for “lone wolf” terror attacks and the Base advocating for an all-out race war with the goal of creating a white ethnostate.40

The NRA Is Complicit in the Attack on the Capitol

Jan 14, 2021

Due at least in part to the gun lobby’s insurrectionist and anti-government messaging, there is significant overlap in goals, tactics, and ideology between hate groups and other armed extremist groups.41 Civilian paramilitary groups like the boogaloo bois,42 the 3%ers,43 and the Oath Keepers44 also engage in firearm and combat training in preparation for civil unrest, which they frequently refer to as a second civil war.45

Though they do not consider themselves hate groups—instead basing their ideologies on a distrust of the government—overtones of racial and ethnic bias are evident in their statements as well their actions. These self-styled militia groups tend to be aggressively anti-immigration, and often anti-Islam.46 While the Oath Keepers’ bylaws specifically bar open racists from becoming members,47 their founder has himself made openly racist remarks in official press releases, suggesting that groups like La Raza and Black Lives Matter are “racist agitators” and “proxy agents of the elites.”48

Despite ideological differences, hate groups and civilian paramilitary groups are united in their commitment to armed opposition to people whom they perceive to be threatening their way of life, and in their penchant for political violence.

January 6th Insurrection

On January 6, 2021, a national spotlight was shone on the danger posed by extremist groups. Symbols of hate, including Confederate flags and gallows, featured prominently at the Capitol attack, and investigative reporters from FRONTLINE and Propublica identified members of several hate groups and other extremists in the crowd. This included members of the Proud Boys, a male chauvinist group with connections to white nationalism known for its involvement in protest-related street brawling; prominent white supremacist internet personality Tim Gionet, who goes by the nickname “Baked Alaska”; a follower of Nick Fuentes, a “white majoritarian” internet personality who “jokingly” suggested killing state legislators days before the Capitol was stormed; and a member of a white supremacist group from California.49

Hate groups and civilian paramilitary groups are united in their commitment to armedopposition to people whom they perceive to be threateningtheir way of life.

The man who was photographed carrying zip-tie handcuffs on the Senate floor and posted on social media encouraging people to “shoot their way in” to the Capitol had previously been fired for talking about killing people of a “particular religion and or race” in his workplace.50 Several members of the paramilitary group the Oath Keepers have since been charged for conspiracy to commit violence.51 Some members have pleaded guilty to or been convicted of the charges against them.52

A number of insurrectionists were armed, in violation of DC’s firearm laws.53 Three of the people arrested for firearm violations in connection to the riots were particularly alarming in the context of armed hate. Two days before the riot, one of the leaders of the Proud Boys was arrested while traveling into DC as a result of a possible hate crime committed against a Black church in December of 2020. He was in possession of two large-capacity magazines when he was arrested. Another man was arrested the evening of the riot, after Capitol police found several firearms, molotov cocktails, and a handwritten note with Rep. André Carson’s name on it, noting that he was “one of two Muslims in House of Reps.”54

A third man was arrested the evening of the Capitol attack at a DC Holiday Inn when, during an investigation relating to texts in which he threatened to kill Speaker Nancy Pelosi using explicit misogynistic language, agents found handguns, an assault rifle, and “hundreds of rounds” of ammunition in his vehicle.55

This last threat exemplifies what appears to be a growing trend of serious threats being made toward female lawmakers in particular, including the plot to kidnap Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer; the numerous threats made toward the congresswomen of color often referred to as “the Squad:” Reps. Ayanna Pressley, Ilhan Omar, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, and Rashida Tlaib; the threats made against Senators Lisa Murkowski and Susan Collins; and the the serious but less high-profile harassment of other female candidates for office across the country.56

A particularly concerning factor in this discussion is the existence of extremists and white supremacists in law enforcement,57 an ongoing problem throughout America’s history. In 2006, the FBI released a report about the dangers of white supremacist infiltration, acknowledging that the Ku Klux Klan’s historical ties to law enforcement and noting that “white supremacist leadership has … engaged in recent rhetoric that encourages followers to infiltrate law enforcement communities.”58 Nationally, the response to this warning has been lackluster, and examples abound of officers who have been caught engaging in hate-motivated behavior facing few to no consequences.59

Similar concerns have been raised about extremist infiltration of the military, especially by the more militant neo-Nazi and civilian paramilitary groups that prioritize recruiting people with combat training. The insurrection at the Capitol may serve as a wakeup call, given that several people with ties to the military were arrested for their participation in the attack.60

It’s long past time for law enforcement and military leadership across the nation to heed this warning and finally tackle the problem of extremism in their ranks.

Armed Intimidation at protests

In many states with weak open carry laws, individuals use firearms to harass and intimidate under the guise of exercising their Second Amendment right.61 For example, in 2015, a group of 250, many armed with assault weapons, gathered in front of a mosque in Phoenix, Arizona, to protest the presence of Islam in the US.62

Though the demonstrators claimed that the weapons were for self defense,63 they clearly also served the purpose of intimidating counter-protesters and mosque attendees.64 While the organizer of the demonstration has been identified as a “potential threat to law enforcement,”65 It does not appear that he or other demonstrators faced any consequences for this instance of armed intimidation.66 In fact, this protest inspired other similar events in several states.67

At the now infamous “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017, hundreds of white nationalists and neo-Nazis congregated to protest the removal of a confederate statue. The event quickly devolved as skirmishes broke out between heavily armed rally attendees and counter-protesters. A Ku Klux Klan Imperial Wizard fired a pistol at peaceful counter-protesters while shouting racial slurs,68 a counter-protester was severely beaten by six rally attendees linked to white supremacist and paramilitary groups,69 and a white supremacist drove a car into a crowd of counter-protesters, killing one young woman and injuring 19 other people.70 The presence of guns at this protest clearly did not serve the purpose of “protecting free speech.” Instead, guns were used primarily by members of hate groups to intimidate, threaten, and incite violence.

Armed Protesters Inspire Fear, Chill Free Speech

Jan 28, 2021

The summer of 2020 presented even more examples of the grave danger posed by armed intimidation at protests. In many communities throughout the country, the movement demanding justice for Black Americans killed by police was met with armed resistance. Despite the fact that nearly all (93%) of the Black Lives Matter protests were peaceful,71 paramilitary groups and other armed civilians showed up in full force at planned protest locations. It is difficult to overlook the fact that these overblown concerns about violent and criminal behavior by protesters aligns closely with common prejudices about Black Americans.

The presence of these armed vigilantes escalated tensions and discouraged people from exercising their First Amendment rights. At least one protest was canceled due to concerns about the presence of paramilitary groups.72 On several occasions, self-styled militia members and other armed citizens fired on protesters. In Austin, Texas, a man drove his car into a march and shot and killed a protester.73

In New Mexico, a protester was shot and injured by an armed civilian at a protest that drew the presence of the “New Mexico Civil Guard,” an armed paramilitary group that Albequerque’s mayor has linked to white supremacy and domestic terrorism.74 In Kenosha, Wisconsin, three protestors were shot, two fatally, by 17-year-old Kyle Rittenhouse who travelled to the town to join a local paramilitary group in ‘protecting businesses.’75 All of these shooters have claimed self-defense, and Kyle Rittenhouse was acquitted of all charges in November 2021. In order to hold these perpetrators to account and prevent future hate-fueled violence, we must strengthen our nation’s gun safety laws.

SUPPORT GUN SAFETY

We’re in this together. To build a safer America—one where children and parents in every neighborhood can learn, play, work, and worship without fear of gun violence—we need you standing beside us in this fight.

Policy Solutions

The problem of armed hate and extremism is multifaceted, ranging from firearm intimidation at protests to ideologically driven mass murder. Thus, the policy solutions to address the different aspects of this critical problem vary. Any efforts to address armed hate must be supported by foundational gun safety policies that can then be built upon.

Pass Universal Background Checks

In order to prohibit people with histories of violence from obtaining guns, a background check must be required for every gun sale. Federal law currently only requires background checks for guns sold by a federally licensed dealer, not for gun transfers between unlicensed individuals who arrange the sale online, in person, or at a gun show. A recent large-scale survey found that 45% of gun owners who acquired a gun online in the past two years did so without any background check.76 Other research has found that around 80% of firearms acquired for criminal purposes are obtained through transfers from unlicensed sellers.77 People have taken advantage of loopholes in the country’s background check system to purchase guns they were ineligible for, which they then used to commit mass shootings78 and kill their family members.79

How COVID-19, Racial Inequity, and Insurrection Make the Case for Background Checks

Lindsay Nichols—Feb 25, 2021

Twenty-one states and the District of Columbia have extended the background check requirement beyond federal law to require a background check on at least some private gun sales. Bipartisan bills to require universal background checks at the federal level, and to partially close the Charleston loophole—which currently allows for firearm sales to proceed before a background check is completed—were introduced in the 116th and 117th Congresses in 2019 and 2021 and passed the House of Representatives, but stalled in the Senate.

On March 2, 2021, these bills were reintroduced in the House alongside their Senate companion, the Background Checks Expansion Act. Both bills have since passed the House. Every state should enact a law requiring background checks for all firearm sales, and Congress must pass legislation to ensure that people with significant histories of violence do not have unfettered access to firearms.

Enact Extreme Risk Protection Order Laws

Extreme risk protection orders (ERPOs) are an important tool for disarming people who pose a clear threat to public safety before they have a chance to hurt themselves or others. ERPOs authorize law enforcement agencies or family members to present sworn evidence to a court that an individual has demonstrated an extreme risk of violence with a firearm. These laws provide similar due process protections to the domestic violence protection and restraining orders that already exist in all 50 states. Currently, 19 states and the District of Columbia have enacted an ERPO or similar law. ERPOs have historically had bipartisan support, and several have been signed into law by Republican governors.80

Extreme risk laws are valuable tools for protecting victims of violent hate because they are issued based on the respondent’s dangerous, threatening, or worrying behavior—whether or not the respondent has committed a criminal act or been diagnosed with a mental health condition. The Parkland shooter, for example, exhibited numerous warning signs prior to the shooting. Though he received mental health care during most of his youth, he was never diagnosed with a serious mental illness. In late 2016, after threatening to harm himself, he was evaluated under Florida’s Baker Act, which allows law enforcement to take a person into custody for up to 72 hours in order to perform a mental health evaluation. Though records from this event are not publicly available, it is clear that this evaluation did not result in any firearm prohibitions. After the Parkland shooting, Florida passed an ERPO law in order to address this gap.

ERPO laws have already played an important role in preventing violent hate and domestic terror incidents. For example, in 2019, prosecutors in Snohomish County, Washington, successfully petitioned a judge to issue an ERPO to remove firearms from the suspected regional leader of the neo-Nazi group Atomwaffen Division, who had been amassing firearms and holding firearm training “hate camps” for other Atomwaffen members in western Washington state.81 If Washington had enacted a version of an ERPO law that depended solely on mental health diagnoses, the court may have been required to dismiss the ERPO petition.

States with ERPO laws must also dedicate resources and attention to implementing these laws so that law enforcement officers and community members understand how to utilize them. In the Buffalo massacre targeting Black Americans, the shooter had previously made a threat to commit a mass shooting at a school. Although state police investigated these allegations, and the shooter was referred for a mental health evaluation and counseling, it does not appear that law enforcement, the school administrator, of family members petitioned for an ERPO to keep the shooter from accessing firearms despite the existence of an ERPO law in New York.82 The proper implementation of these laws is critical to ensure that they will be maximally effective.83

Each state should enact an ERPO law that empowers courts to proactively protect the public and issue ERPOs based on objective evidence of behavioral threats, with or without evidence that a respondent has been diagnosed as mentally ill, and to invest in proper implementation of the law. Giffords urges Congress to pass the Extreme Risk Protection Order Act of 2021 introduced by Senator Feinstein and Representative Carbajal of California, which would provide grants to states to implement extreme risk laws, and the Federal Extreme Risk Protection Order Act of 2021 introduced by Representative McBath of Georgia, which would create a federal ERPO process, filling the critical gap in states that do not have an ERPO law and helping to prevent mass violence, domestic terror, and threats to national security.

Regulate Military-Style Weapons and Large-Capacity Magazines

Source

Charles DiMaggio et al., “Changes in US Mass Shooting Deaths Associated with the 1994–2004 Federal Assault Weapons Ban: Analysis of Open–source Data,” Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 86, no. 1 (2019): 11–19.

Though the majority of mass shooters display warning signs, not every person who poses a threat to public safety can be identified and disarmed before a shooting occurs. Increased regulation of military-style assault weapons and large-capacity magazines can help reduce the number of people killed and injured when attacks do occur. Currently, nine states and the District of Columbia regulate military-style weapons more strictly than other guns, and 10 states and the District of Columbia ban large-capacity magazines, the most recent state being Washington which enacted a ban on magazines that can hold more than 10 rounds in 2022.

Studies have found that even during the modest 10-year federal ban on the sale of assault weapons and large-capacity magazines, mass shooting fatalities were reduced by 70% compared to the periods before and after the ban.84 Studies have also found that in mass shootings where a shooter used weapons equipped with large-capacity magazines, more than twice as many people were shot and 57% more victims were killed compared to mass shootings where the gunman used standard magazines.85

Behind those data points are personal stories of tragedy or survival. A classroom of children escaped at Sandy Hook Elementary School when the shooter had to stop to reload. In the 2011 Tucson shooting that severely injured our organization’s founder, Gabby Giffords, a nine-year-old girl was struck and killed by the shooter’s 13th bullet. She might still be alive today if he had to stop to reload after ten rounds, instead of 33. Thoroughly regulating the public’s access to these military-style weapons by treating their sale, manufacture, and ownership similarly to machine guns can protect vulnerable groups from large-scale massacres like the 2016 Pulse shooting.

Prohibit Guns at Protests

As described earlier, people motivated by hate and empowered by weak public carry laws use firearms to intimidate and harass members of protected groups in public spaces. When this occurs in places where people are exercising their constitutional rights to assemble, participate in the legislative process, and vote, important American freedoms are in jeopardy.

There has been an increased use of guns over the past two years to suppress such democratic activities but the risk of disenfranchisement and exclusion from First Amendment activities falls disproportionately on people of color. For example, a lawsuit filed in March 2022 alleges that in Colorado, pro-Trump armed activists are going door-to-door in areas where large numbers of people of color reside asking them how they voted and photographing their homes.

Laws that limit where and how people can carry firearms in public spaces can be used to block this type of intimidation and protect the rights of all people to safely enjoy public spaces and exercise First Amendment freedoms.

Trump Incites White Armed Protesters

Laura Cutilletta—Aug 28, 2020

Though there are few existing federal restrictions on public carrying of firearms, both the federal government and state governments have the authority to regulate open carry to discourage firearm intimidation.

Some states have heeded this call based on the events of 2020 and 2021. In 2020, Virginia prohibited firearms in and around the state capitol and in state owned buildings or offices where state employees regularly work. It also allowed local governments to prohibit guns at protests and permitted demonstrations. Washington State passed similar legislation in 2021 banning guns in areas of the state capitol including any state legislative office, and public legislative hearings or meetings. It also prohibited guns at protests and permitted demonstrations. Oregon also prohibited guns in the state capitol in 2021.

Over the past two years, states have also taken steps to protect voting and the counting of ballots from armed intimidation. In 2021, Virginia prohibited guns at the polls and locations where votes are being counted. Colorado and Washington State passed similar laws in 2022. Also this year, Washington State prohibited guns at voter registration offices and school board meetings, and prohibited open carry in local government buildings used for meetings or hearings.

More states and the federal government should prohibit firearms at protests, demonstrations, government buildings, and other civic events. To address more instances of firearm intimidation, states and the federal government should consider broader restrictions on carrying firearms, especially assault weapons, in public streets, parks, and other public spaces.

Disarm Hate Crime Offenders

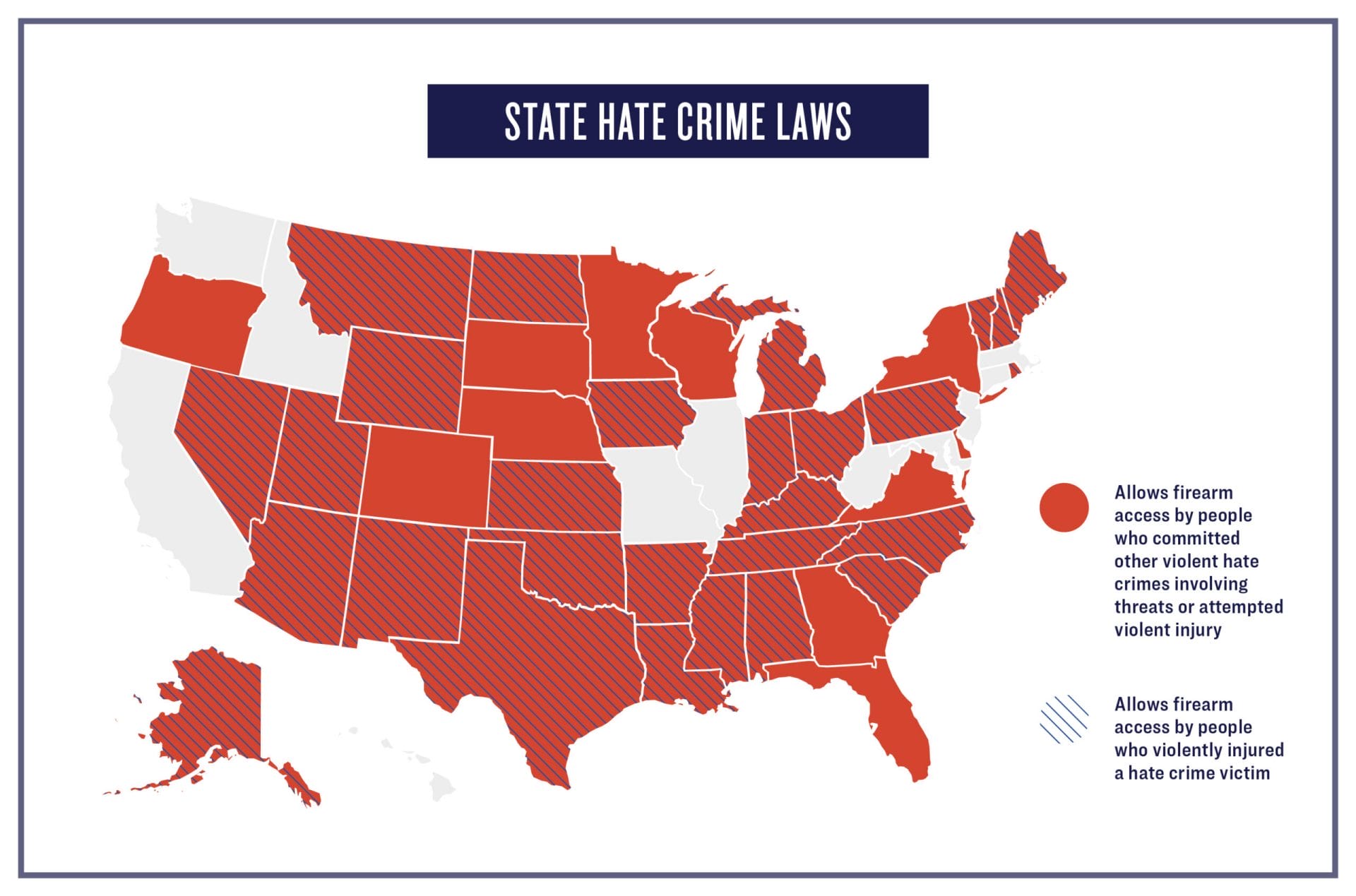

Currently, the only criminal convictions that are firearm-prohibiting everywhere in the country are felonies and certain misdemeanor domestic violence offenses. This means that people convicted of other violent misdemeanors—including violent hate-motivated crimes involving serious bodily injury—remain eligible to possess firearms under federal law and under the laws of most states. As described in greater detail in the appendix of this report, the laws of 28 states authorize people convicted of violently injuring a victim in a hate crime to keep and purchase guns immediately after conviction. An even larger number of states authorize people convicted of other violent hate crimes—including those convicted of making serious threats of violence, attempting to inflict bodily injury, or threateningly brandishing firearms in a hate crime—to access weapons.

Source: Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence

Several states have strong laws prohibiting firearm possession by people convicted of violent hate crimes. For example, in 2017, California’s legislature unanimously passed the Disarm Hate Act, sponsored by Giffords, to prohibit people from accessing firearms for 10 years after they are convicted of a hate crime. California law also generally prohibits people from accessing firearms for 10 years after they have been convicted of felonies or of misdemeanors involving violence or the misuse of deadly weapons. New Jersey has a similar law which permanently prohibits people convicted of violent hate crimes from possessing firearms. Other states charge all or most violent hate crimes as felonies, and prohibit all people convicted of felonies from possessing firearms. States with this type of law include Missouri, Idaho, and West Virginia. Specific suggestions for how each state can prohibit violent hate misdemeanants from possessing firearms are included in the appendix.

The Disarm Hate Act, introduced by Representative Cicilline of Rhode Island and Senator Casey of Pennsylvania in the 116th Congress, would ensure that people who have already escalated bigotry into criminal threats and violence are prevented from acquiring and possessing guns. The legislation would generally prohibit people from acquiring and possessing firearms if they have been convicted of hate motivated misdemeanors that involve the use or attempted use of physical force, the threatened use of a deadly weapon, or other credible threats to physical safety.86 The bill received a mark-up in the House Judiciary Committee but never moved to the Floor for a vote. In the 117th Congress, the Disarm Hate bill has not had any movement. To respond to an alarming growing tide of violent hate and prevent acts of bigoted domestic terror, the Disarm Hate Act should be re-introduced and passed into law.

Because the federal Disarm Hate Act takes state hate crime convictions into account, states should still make the changes suggested in the 50-state appendix below in order for the prohibition to apply evenly across the country. If the Disarm Hate Act were enacted with state hate crime laws as they currently stand, two people who commit the same offense in two different states would not necessarily both become subject to the federal firearm prohibition.

For example, a person who commits a misdemeanor assault upon a transgender woman because of her gender identity can be prosecuted for and convicted of a bias-motivated violent misdemeanor in New Mexico, which would activate the Disarm Hate Act’s firearm prohibition. However, if someone were to commit the same offense in Florida, the act’s firearm prohibition would not apply, because gender identity is not a protected characteristic in the state, so the bias motivation could not be prosecuted. Amending state laws to align with federal law and protect all victims of hate would help ensure that all communities are safer.

Conclusion

Violent hate and hate-fueled extremism is a growing threat to public safety. From armed intimidation at peaceful protests to white supremacist groups storming the United States Capitol, easy access to firearms and hate-fueled individuals are a deadly combination. And the problem is only growing in severity: hate groups are proliferating and hate crimes are becoming more frequent and more frequently violent. In recent years, reported increases in hate-fueled violence led the FBI to elevate “racially motivated violent extremism” to a top level priority threat. Lawmakers at the state and federal levels must take immediate action to address this threat.

Our nation’s weak gun laws, which allow individuals convicted of violent hate crimes to purchase and possess deadly weapons, put members of vulnerable communities—like the 10 Black Americans murdered at a Buffalo grocery store or the 49 people killed at Pulse nightclub—in grave danger. This must change. Lawmakers have the power to respond to protect all Americans from armed and violent hate. It’s long past time that they show the courage to do so.

MEDIA REQUESTS

Our experts can speak to the full spectrum of gun violence prevention issues. Have a question? Email us at media@giffords.org.

Contact

Appendix

The following resources provide an overview of state laws in the recommended policy categories, as well as other resources on each topic. The catalogue of Disarm Hate laws is the most comprehensive 50-state analysis to date detailing access to guns by violent hate crime offenders.

A number of states have laws that exceed weak or nonexistent federal laws in each category. While the federal government should act to strengthen our laws at the national level, courageous state legislators also have an opportunity to step up in order to keep all Americans safe from gun violence.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Background Checks

Extreme Risk Protection Orders

Assault Weapons

Large-Capacity MAgazines

Open & Public Carry

SPOTLIGHT

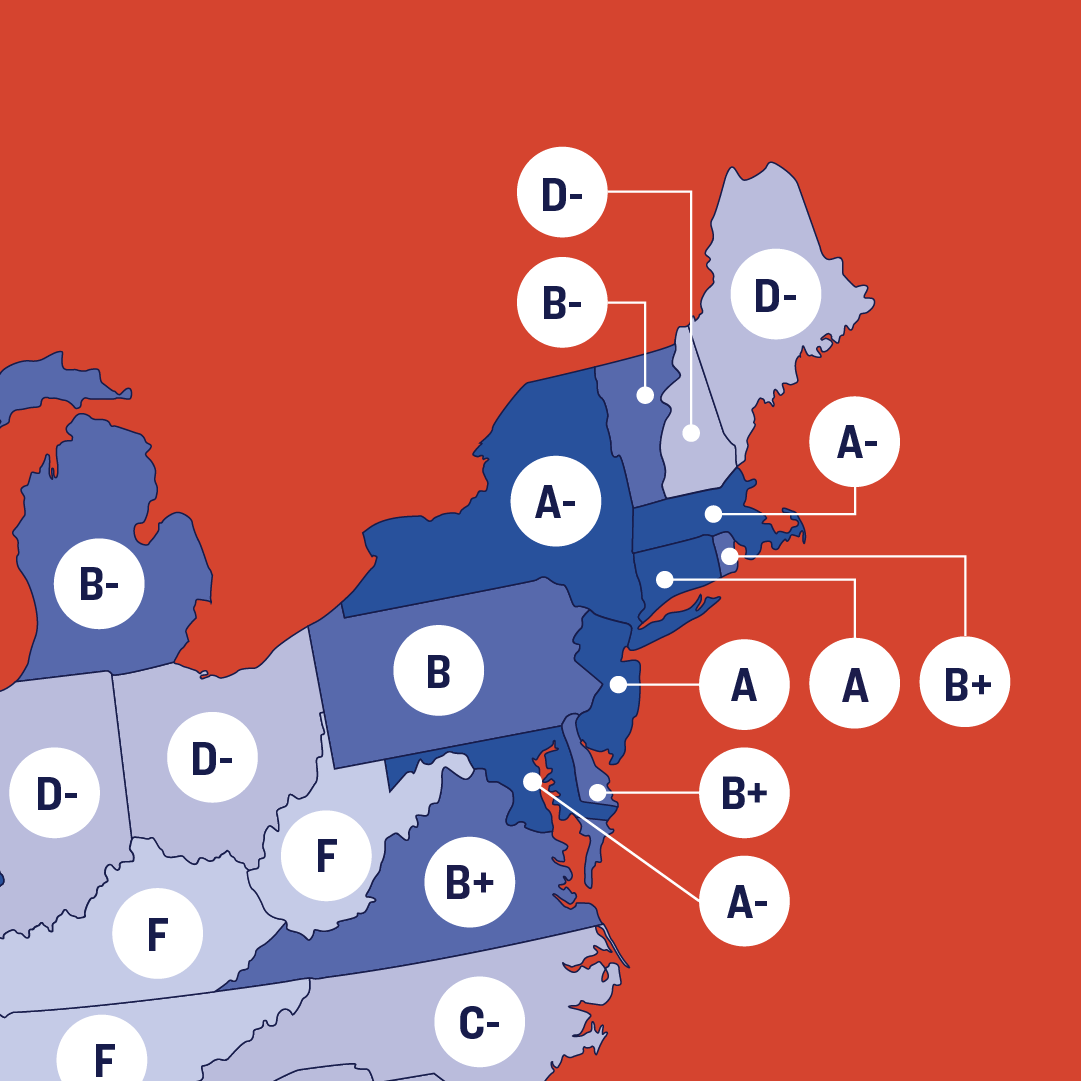

GUN LAW SCORECARD

The data is clear: states with stronger gun laws have less gun violence. See how your state compares in our annual ranking.

Read More

JOIN THE FIGHT

Over 40,000 Americans lose their lives to gun violence every year. Giffords Law Center is leading the fight to save lives by championing gun safety policies and holding the gun lobby accountable. Will you join us?

- Hannah Allam, “FBI Announces That Racist Violence Is Now Equal Priority To Foreign Terrorism,” NPR, February 10, 2020, https://www.npr.org/2020/02/10/804616715/fbi-announces-that-racist-violence-is-now-equal-priority-to-foreign-terrorism; Erin Donaghue, “Racially-motivated violent extremists elevated to “national threat priority,” FBI director says,” CBS News, February 5, 2020, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/racially-motivated-violent-extremism-isis-national-threat-priority-fbi-director-christopher-wray/.[↩]

- Department of Homeland Security, “National Terrorism Advisory System Bulletin,” January 27, 2021, https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/ntas/alerts/21_0127_ntas-bulletin.pdf.[↩]

- Greg Miller, “Senior counterterrorism official expresses concern about access in U.S. to lethal weaponry,” Washington Post, December 22, 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/senior-counterterrorism-official-expresses-concern-about-access-in-us-to-lethal-weaponry/2017/12/21/dad95cce-e664-11e7-833f-155031558ff4_story.html.[↩]

- “Hate Crimes,” Federal Bureau of Investigation, last accessed January 14, 2020, https://www.fbi.gov/investigate/civil-rights/hate-crimes.[↩]

- McDevitt J., Balboni J., Garcia L., and Gu J. (2001). “Consequences for victims: A comparison of bias- and non-bias-motivated assaults,” American Behavioral Scientist 45, 697-713. doi:10.1177/0002764201045004010[↩]

- Holly Lebowitz Rossi, “For synagogues, High Holidays welcome is complicated by security needs,” Religion News Service, September 24, 2019, https://religionnews.com/2019/09/24/for-synagogues-high-holidays-welcome-is-complicated-by-security-needs/; Faygie Holt, “Following Pittsburgh and Poway, security has become top priority at Jewish summer camps,” Jewish News, June 20, 2019, http://www.jewishaz.com/community/following-pittsburgh-and-poway-security-has-become-top-priority-at/article_7f47a5c8-936f-11e9-a6a3-cfbb1950c336.html.[↩]

- Noah Remnick, “At Stonewall Inn, a Gay Rights Landmark, a Vigil in Pride and Anger,” New York Times, June 12, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/06/13/nyregion/at-stonewall-inn-a-gay-rights-landmark-a-vigil-in-pride-and-anger.html?_r=0.[↩]

- Giffords Law Center analysis of FBI UCR Hate Crime Data, Federal Bureau of Investigation, “Crime Data Explorer,” last accessed May 17, 2022, https://crime-data-explorer.fr.cloud.gov/pages/explorer/crime/hate-crime.[↩]

- Id.[↩]

- Id.[↩]

- Note that because NCVS is a survey of a person’s history of victimization, it does not count homicides. United States Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, “Hate Crime Victimization, 2005–2019,” September 21, 2021, https://bjs.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh236/files/media/document/hcv0519_1.pdf; Federal Bureau of Investigation, “Crime Data Explorer: Hate Crime,” last accessed May 17, 2022, https://crime-data-explorer.fr.cloud.gov/pages/explorer/crime/hate-crime.[↩]

- Federal Bureau of Investigation, “Services,” last accessed February 9, 2020, https://www.fbi.gov/services/cjis/ucr.[↩]

- Federal Bureau of Investigation, “Data Collection: National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS),” last accessed February 9, 2020, https://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=dcdetail&iid=245.[↩]

- United States Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, “Hate Crime Victimization, 2005–2019,” September 21, 2021, https://bjs.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh236/files/media/document/hcv0519_1.pdf.[↩]

- See e.g., Cady Lang, “Hate Crimes Against Asian Americans Are on the Rise. Many Say More Policing Isn’t the Answer,” Time, February 18, 2021, https://time.com/5938482/asian-american-attacks/.[↩]

- Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism, “FACT SHEET: Anti-Asian Prejudice March 2021,” CSU San Bernardino, March 2021, https://www.csusb.edu/sites/default/files/FACT%20SHEET-%20Anti-Asian%20Hate%202020%20rev%203.21.21.pdf.[↩]

- AAPI Data, “Press Release: New Survey from Momentive and AAPI Data Offers Important Corrective on Hate in America,” news release, March 16, 2022 http://aapidata.com/blog/discrimination-survey-2022/.[↩]

- Federal Bureau of Investigation, “Crime Data Explorer: Hate Crime,” last accessed May 17, 2022, https://crime-data-explorer.fr.cloud.gov/pages/explorer/crime/hate-crime.[↩]

- Id.[↩]

- Id.[↩]

- Hannah Allam, “FBI Announces That Racist Violence Is Now Equal Priority To Foreign Terrorism,” NPR, February 10, 2020, https://www.npr.org/2020/02/10/804616715/fbi-announces-that-racist-violence-is-now-equal-priority-to-foreign-terrorism.[↩]

- Erin Donaghue, “Racially-motivated violent extremists elevated to “national threat priority,” FBI director says,” CBS News, February 5, 2020, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/racially-motivated-violent-extremism-isis-national-threat-priority-fbi-director-christopher-wray/.[↩]

- Federal Bureau of Investigation, “FBI Statement Regarding Shootings in El Paso and Dayton,” Press Release, August 4, 2019, https://www.fbi.gov/news/pressrel/press-releases/fbi-statement-regarding-shootings-in-el-paso-and-dayton; Michael C. McGarrity and Calvin A. Shivers, “Confronting White Supremacy,” Statement Before the House Oversight and Reform Committee, Subcommittee on Civil Rights and Civil Liberties; June 4, 2019, https://www.fbi.gov/news/testimony/confronting-white-supremacy.[↩]

- United States Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation, Criminal Justice Information Services Division, “National Instant Criminal Background Check System (NICS) Section 2018 Operations Report,” last accessed February 9, 2020, https://www.fbi.gov/file-repository/2018-nics-operations-report.pdf/view.[↩]

- In four of those states, these offenses would generally be treated as felonies and trigger federal firearm restrictions, but in at least 24 states, people convicted of violently injuring hate crime victims would be able to lawfully pass a background check to acquire new weapons under both state and federal law immediately after conviction.[↩]

- United States Department of Justice, “Hate Crime Case Examples,” last accessed February 9, 2020, https://www.justice.gov/hatecrimes/hate-crimes-case-examples#.[↩]

- Jadeline Masucci and Lynn Langton, “Hate Crime Victimization, 2004-2015,” Bureau of Justice Statistics, June 2017, https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/hcv0415.pdf.[↩]

- Garen J. Wintemute, “Prior Misdemeanor Convictions As A Risk Factor For Later Violent And Firearm-Related Criminal Activity Among Authorized Purchasers Of Handguns,” 280 JAMA (1998): 2083, http://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/188297; Garen J. Wintemute, et al., “Subsequent Criminal Activity among Violent Misdemeanants Who Seek to Purchase Handguns: Risk Factors and Effectiveness of Denying Handgun Purchase,” 285 JAMA (2001): 1019, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11209172.[↩]

- Chelsea Parsons and Eugenio Weigend Vargas, “Hate and Guns: a Terrifying Combination,” Center for American Progress, 2016, https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/guns-crime/reports/2016/02/24/131670/hate-and-guns-a-terrifyingcombination/.[↩]

- Daniel Burke, “The four reasons people commit hate crimes,” CNN, June 12, 2017, https://www.cnn.com/2017/06/02/us/who-commits-hate-crimes/index.html.[↩]

- Steven Windisch, et al., “Understanding the micro-situational dynamics of White Supremacist Violence in the US;” Perspectives on Terrorism 12, no. 6 (December 2018), https://www.universiteitleiden.nl/binaries/content/assets/customsites/perspectives-on-terrorism/2018/issue-6/a2-windisch-et-al.pdf.[↩]

- Nicholas Riccardi, “Mother describes border vigilante killings in Arizona,” Los Angeles Times, January 25, 2011, https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2011-jan-25-la-na-minutemen-murder-20110126-story.html; Jesse McKinley & Malia Wollan, “New Border Fear: Violence by a Rogue Militia,” New York Times, June 26, 2009, https://www.nytimes.com/2009/06/27/us/27arizona.html; Scott North & Elaine Helm, “Murder suspect on the military veteran he claims to be,” HeraldNet, June 18, 2009, https://web.archive.org/web/20090623122134/http://www.enterprisenewspapers.com/article/20090618/NEWS01/706189914/0/ETPZoneLT.[↩]

- Id.[↩]

- In March of 2020, James Mason, a neo-Nazi and advisor to Atomwaffen, announced that the group was disbanding, shortly after five alleged members were arrested by the FBI. It is unclear whether or not this claim is true. https://www.vice.com/amp/en_us/article/qjdnam/audio-recording-claims-neo-nazi-terror-group-is-disbanding[↩]

- Ben Makuch, “Audio Recording Claims Neo-Nazi Terror Group Is Disbanding,” Vice, March 15, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/morning-mix/wp/2018/01/29/suspects-in-five-homicides-reportedly-tied-to-macabre-neo-nazi-group/.[↩]

- “Documenting Hate: New American Nazis,” Frontline and PBS, November 20, 2018, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/film/documenting-hate-new-american-nazis/[↩]

- Jason Wilson, “Revealed: the true identity of the leader of an American neo-Nazi terror group,” The Guardian, January 23, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jan/23/revealed-the-true-identity-of-the-leader-of-americas-neo-nazi-terror-group; Ben Makuch, “Neo-Nazi Terror Group Harbouring Missing Ex-Soldier: Sources,” Vice News, December 5, 2019, https://www.vice.com/en_ca/article/8xwwaa/neo-nazi-terror-group-harbouring-missing-ex-soldier-patrik-mathews-sources; NPR has also reported that The Base conducts firearm training to prepare its members for a “race war.” See Bill Chappell, et al., “3 Alleged Members Of Hate Group ‘The Base’ Arrested In Georgia, Another In Wisconsin, NPR, January 17, 2020, https://www.npr.org/2020/01/17/797399834/3-alleged-members-of-hate-group-the-base-arrested-in-georgia.[↩]

- Bill Chappell, et al., “3 Alleged Members Of Hate Group ‘The Base’ Arrested In Georgia, Another In Wisconsin,” NPR, January 17, 2020, https://www.npr.org/2020/01/17/797399834/3-alleged-members-of-hate-group-the-base-arrested-in-georgia.[↩]

- Id.[↩]

- Patrice Taddonio, “Inside a Neo-Nazi Group With Members Tied to the U.S. Military,” Frontline and ProPublica, November 20, 2018, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/article/inside-a-neo-nazi-group-with-members-tied-to-the-u-s-military/; Jason Wilson, “Revealed: the true identity of the leader of an American neo-Nazi terror group,” The Guardian, January 23, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jan/23/revealed-the-true-identity-of-the-leader-of-americas-neo-nazi-terror-group; https://www.adl.org/resources/backgrounders/the-base. These hate camps may be illegal—many states, including states where these hate camps have been held, have laws restricting the formation of private militias and paramilitary training. For example, FRONTLINE and ProPublica found that Atomwaffen held a hate camp in Death Valley national park, which is on the border of California and Nevada. California prohibits teaching or assembling to learn “the use, application, or making of any firearm … knowing or having reason to know or intending that these objects or techniques will be unlawfully employed for use in, or in the furtherance of a civil disorder.” In Nevada it is “unlawful for any body of individuals other than the municipal police, university or public school cadets or companies, militia of the State or troops of the United states, to associate themselves together as a military company with arms without the consent of the governor.” Whether or not these hate camps are illegal, their existence, and the future violence that they promote, is extremely alarming.[↩]

- “The Role of Guns & Armed Extremism in the Attack on the U.S. Capitol,” Everytown for Gun Safety, January 28, 2021, https://everytownresearch.org/report/armed-extremism-us-capitol/.[↩]

- Benjamin Goggin and Rachel E. Greenspan, “Who are the Boogaloo Bois? A man who shot up a Minneapolis police precinct was associated with the extremist movement, according to unsealed documents,” Insider, October 26, 2020, https://www.insider.com/boogaloo-bois-protest-far-right-minneapolis-extremist-guns-hawaiian-shirts-2020-5.[↩]

- Vice Staff, “This Three Percenter Militia Is Hell-Bent on Keeping Its Guns,” Vice, October 18, 2017, https://www.vice.com/en/article/ne78pk/this-three-percenter-militia-is-hell-bent-on-keeping-its-guns.[↩]

- Mike Giglio, “A Pro-Trump Militant Group Has Recruited Thousands of Police, Soldiers, and Veterans,” The Atlantic, November 2020, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2020/11/right-wing-militias-civil-war/616473/[↩]

- See, e.g. Benjamin Goggin and Rachel E. Greenspan, “Who are the Boogaloo Bois? A man who shot up a Minneapolis police precinct was associated with the extremist movement, according to unsealed documents,” Insider, October 26, 2020, https://www.insider.com/boogaloo-bois-protest-far-right-minneapolis-extremist-guns-hawaiian-shirts-2020-5; Mike Giglio, “A Pro-Trump Militant Group Has Recruited Thousands of Police, Soldiers, and Veterans,” The Atlantic, November 2020, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2020/11/right-wing-militias-civil-war/616473/.[↩]

- Vice Staff, “This Three Percenter Militia Is Hell-Bent on Keeping Its Guns,” Vice, October 18, 2017, https://www.vice.com/en/article/ne78pk/this-three-percenter-militia-is-hell-bent-on-keeping-its-guns[↩]

- “Oath Keepers Bylaws,” last accessed February 9, 2021, https://oathkeepers.org/bylaws/#article-viii.[↩]

- Southern Poverty Law Center, “Oath Keepers,” last accessed February 9, 2021, https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/extremist-files/group/oath-keepers.[↩]

- A.C. Thompson and Ford Fischer, “Members of Several Well-Known Hate Groups Identified at Capitol Riot,” Frontline and ProPublica, January 9, 2021, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/article/several-well-known-hate-groups-identified-at-capitol-riot/.[↩]

- Associated Press, “Veteran at Capitol with zip-tie handcuffs during riot aimed ‘to take hostages’: Prosecutor,” KTLA, January 14, 2021, https://ktla.com/news/nationworld/veteran-at-capitol-with-zip-tie-handcuffs-during-riot-aimed-to-take-hostages-prosecutor/.[↩]

- Charlie Savage, et al., “‘This Kettle Is Set to Boil’: New Evidence Points to Riot Conspiracy,” New York Times, January 19, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/19/us/politics/oath-keepers-capitol-riot.html.[↩]

- Jan Wolfe, “Oath Keepers member pleads guilty to sedition in U.S. Capitol attack,” Yahoo News, May 4, 2022, https://news.yahoo.com/oath-keepers-member-plead-guilty-154720956.html; Jacques Billeaud, “Georgia Man 2nd Rioter Convicted of Seditious Conspiracy,” Associated Press, April 29, 2022, https://www.usnews.com/news/politics/articles/2022-04-29/georgia-man-2nd-rioter-convicted-of-seditious-conspiracy.[↩]

- Jennifer Mascia, “A Running List of Gun Arrests Tied to the U.S. Capitol Attack,” The Trace, updated February 5, 2021, https://www.thetrace.org/2021/01/capitol-riot-firearms-arrests-proud-boys/.[↩]

- Annie Grayer and Ryan Nobles, “Lawmakers express fears about Capitol safety while tensions grow over new security measures,” CNN, January 13, 2021, https://www.cnn.com/2021/01/13/politics/congress-member-safety/index.html; Special Agent Lawrence Anyaso, “Affidavit in Support of Criminal Complaint,” January 7, 2021, https://assets.documentcloud.org/documents/20446319/us-v-lonnie-l-coffman-affidavit.pdf.[↩]

- “Man arrested after allegedly texting about ‘putting a bullet’ in Nancy Pelosi,” CBS News, January 12, 2021, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/man-allegedly-considering-trying-to-kill-nancy-pelosi-arrested-in-dc/.[↩]

- John Flesher, “6 men indicted in alleged plot to kidnap Michigan governor,” Associated Press, December 17, 2020, https://apnews.com/article/gretchen-whitmer-michigan-indictments-coronavirus-pandemic-traverse-city-10f7e02c57004da9843f89650edd4510; Dora Mekouar, “For Women in Politics, Being Terrorized Comes With the Job,” Voice of America, August 23, 2019, https://www.voanews.com/usa/all-about-america/women-politics-being-terrorized-comes-job; Maggie Astor, “For Female Candidates, Harassment and Threats Come Every Day,” New York Times, August 24, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/24/us/politics/women-harassment-elections.html; “Ilhan Omar: Muslim lawmaker sees rise in death threats after Trump tweet,” BBC News, April 15, 2019, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-47938268; Erin Snodgrass, “Rep. Rashida Tlaib tearfully shared her account of the Capitol riots, recalling her trauma of the death threats she’s received,” Business Insider, February 4, 2021, https://www.businessinsider.com/rashida-tlaib-broke-down-while-discussing-death-threats-shes-received-2021-2; Sarah Elbeshbishi, “Texas man charged after storming US Capitol, making death threats against Rep. Ocasio-Cortez and police officer,” USA Today, January 23, 2021, https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2021/01/23/fbi-charges-capitol-rioter-threat-kill-alexandria-ocasio-cortez/6687691002/.[↩]

- Michael German, “Hidden in Plain Sight: Racism, White Supremacy, and Far-Right Militancy in Law Enforcement,” Brennan Center for Justice, August 27, 2020, https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/hidden-plain-sight-racism-white-supremacy-and-far-right-militancy-law.[↩]

- Federal Bureau of Investigation, “White Supremacist Infiltration of Law Enforcement,” FBI Intelligence Assessment, 17 October 2006, http://s3.documentcloud.org/documents/402521/doc-26-white-supremacist-infiltration.pdf.[↩]

- Michael German, “Hidden in Plain Sight: Racism, White Supremacy, and Far-Right Militancy in Law Enforcement,” Brennan Center for Justice, August 27, 2020, https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/hidden-plain-sight-racism-white-supremacy-and-far-right-militancy-law.[↩]

- Eric Schmitt, et al., “Pentagon Accelerates Efforts to Root Out Far-Right Extremism in the Ranks,” New York Times, January 18, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/18/us/politics/military-capitol-riot-inauguration.html.[↩]

- Though the landmark 2008 Heller Supreme Court decision did not name public or open carry as a core element of the rights protected by the Second Amendment, gun rights proponents regularly claim that open carry is a constitutional right.[↩]

- Evan Wyloge, “Hundreds gather in Arizona for armed anti-Muslim Protest,” Washington Post, May 30, 2015, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/post-nation/wp/2015/05/30/hundreds-gather-in-arizona-for-armed-anti-muslim-protest/.[↩]

- Id.[↩]

- Daniel González, “Muslims brace for series of anti-Islam protests in Phoenix, around U.S.,” AZ Central, October 9, 2015, https://www.azcentral.com/story/news/local/phoenix/2015/10/09/anti-islam-protests-phoenix-muslims-safety-precautions/73597738/; Brenna Goth & Jim Walsh, “A clash of freedoms during Phoenix mosque protest,” AZ Central, May 30, 2015, https://www.azcentral.com/story/news/local/phoenix/2015/05/29/law-enforcement-prepares-protest-outside-phoenix-mosque/28136557/.[↩]

- Graham Rayman, “EXCLUSIVE: FBI warns NY police about anti-Islam Arizona man who may be headed to state to confront Muslim group,” NY Daily News, November 27, 2015, https://www.nydailynews.com/news/crime/fbi-warns-ny-police-anti-islam-arizona-man-article-1.2448001.[↩]

- The organizer of this demonstration has since been charged with several federal felony counts for an unrelated event—the armed occupation of Malheur National Wildlife Refuge. He pled guilty to a federal conspiracy charge as part of a plea bargain. See Maxine Bernstein, “New six-count indictment unsealed in Malheur refuge occupation case,” The Oregonian, updated Jan 9, 2019, http://www.oregonlive.com/oregon-standoff/2016/03/new_six-count_indictment_unsea.html; Rebecca Wollington, “Oregon standoff defendant Jon Ritzheimer pleads guilty in federal conspiracy case,” The Oregonian, updated January 9, 2019, https://www.oregonlive.com/oregon-standoff/2016/08/oregon_standoff_defendant_jon_1.html.[↩]

- Niraj Warikoo, “Anti-Islam rallies across USA making Muslims wary,” USA Today, updated October 10, 2015, https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation-now/2015/10/09/anti-islam-rallies-across-usa-making-muslims-wary/73672674/.[↩]

- Ryan Lenz, “Man Who Fired Weapon At Charlottesville Counterprotesters Identified as Ku Klux Klan Imperial Wizard,” Southern Poverty Law Center, August 29, 2017, https://www.splcenter.org/hatewatch/2017/08/29/man-who-fired-weapon-charlottesville-counterprotesters-identified-ku-klux-klan-imperial.[↩]

- Ian Shapira, “The parking garage beating lasted 10 seconds. DeAndre Harris still lives with the damage,” Washington Post, September 16, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/the-parking-garage-beating-lasted-10-seconds-deandre-harris-still-lives-with-the-damage/2019/09/16/ca6daa48-cfbf-11e9-87fa-8501a456c003_story.html.[↩]

- Hawes Spencer & Ricard Pérez-Peña, “Murder Charge Increases in Charlottesville Protest Death,” New York Times, December 14, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/14/us/charlottesville-fields-white-supremists.html.[↩]

- Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project, “Demonstrations & Political Violence In America New Data For Summer 2020,” September 2020, https://acleddata.com/2020/09/03/demonstrations-political-violence-in-america-new-data-for-summer-2020/.[↩]

- Nicolle Okoren, “The birth of a militia: how an armed group polices Black Lives Matter protests,” The Guardian, July 27, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/jul/27/utah-militia-armed-group-police-black-lives-matter-protests.[↩]

- David Montgomery and Manny Fernandez, “Garrett Foster Brought His Gun to Austin Protests. Then He Was Shot Dead,” New York Times, July 26, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/26/us/austin-shooting-texas-protests.html; there were over 100 incidents of vehicles being driven into Black Lives Matter protests between May 26th and September 5th of 2020. Of those, a researcher determined at least 43 of them to be malicious in intent. Grace Hauck, “Cars have hit demonstrators 104 times since George Floyd protests began,” USA Today, updated September 27, 2020, https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2020/07/08/vehicle-ramming-attacks-66-us-since-may-27/5397700002/. In one of these incidents, when a man drove through a crowd of protestors, one of the protestors opened fire, injuring two other protestors. Associated Press and Jesse Paul, “Police are investigating after car drives through crowd and protesters are shot in Aurora,” The Colorado Sun, July 26, 2020, https://coloradosun.com/2020/07/26/aurora-protest-shooting-vehicle/.[↩]

- Andrew Hay, “Mayor: Militia at violent protest linked to white supremacy,” Mercury News, June 16, 2020, https://www.mercurynews.com/2020/06/16/mayor-militia-at-violent-protest-linked-to-white-supremacy/[↩]

- Gina Barton, “’That’s the shooter’: Witnesses describe the night Kyle Rittenhouse opened fire in Kenosha,” USA Today, August 31, 2020, https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2020/08/31/witnesses-kenosha-shooting-see-kyle-rittenhouse-shoot-protest-jacob-blake/5675987002/.[↩]

- Matthew Miller, Lisa Hepburn, and Deborah Azrael, “Firearm Acquisition Without Background Checks: Results of a National Survey,” Annals of Internal Medicine 166, no. 4 (2017): 233–239.[↩]

- Katherine A. Vittes, Jon S. Vernick, and Daniel W. Webster, “Legal Status and Source of Offenders’ Firearms in States with the Least Stringent Criteria for Gun Ownership,” Injury Prevention 19, no. 1 (2013): 26-31[↩]

- Ryan W. Miller, “Gunman in Texas Shooting Bought Gun in Private Sale: Here’s What We Know,” USA Today, September 3, 2019, https://bit.ly/2khMbBp.[↩]

- Alison Dirr, “Five Years Apart, Armslist was Source of Guns in High-Profile Domestic Violence Deaths,” Appleton Post-Crescent, September 19, 2018, https://www.postcrescent.com/story/news/crime/2018/09/19/guns-harrison-murder-suicide-azana-shooting-found-same-website/1224081002/; Kimber Laux, “Report reveals details about North Las Vegas day care shooting,” Las Vegas Review Journal, June 17, 2016, https://www.reviewjournal.com/crime/homicides/report-reveals-details-about-north-las-vegas-day-care-shooting/.[↩]

- State ERPO laws that were signed by Republican governors include those enacted in Florida, Indiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, and Vermont.[↩]

- Chris Ingalls, “Police seize guns from avowed neo-Nazi in Snohomish County,” NBC King5, updated October 18, 2019, https://www.king5.com/article/news/investigations/police-seize-guns-from-avowed-neo-nazi-snohomish-county/281-400146c7-5c81-4c8d-80d6-78f877977340.[↩]

- Stephen T. Watson et al., “Gunman, 18, drove more than 3 hours to Buffalo to commit hate crime, officials say,” The Buffalo News, May 14, 2022, https://buffalonews.com/news/local/gunman-18-drove-more-than-3-hours-to-buffalo-to-commit-hate-crime-officials-say/article_f9ef9bac-d3d9-11ec-9eaf-cbcafe308f9c.html.[↩]

- Julia Weber, “Implementation Toolkit for Gun Safety Laws,” Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence, July 12, 2021, https://giffords.org/lawcenter/report/implementation-toolkit-for-gun-safety-laws/.[↩]

- Charles DiMaggio, et al., “Changes in US Mass Shooting Deaths Associated with the 1994–2004 Federal Assault Weapons Ban: Analysis of Open–source Data,” Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 86, no. 1 (2019): 11–19.[↩]

- Mayors Against Illegal Guns, “Analysis of Recent Mass Shootings,” US Department of Justice, Office of Justice programs, 2013, https://www.ojp.gov/library/abstracts/analysis-recent-mass-shootings.[↩]

- In the Disarm Hate Act, a misdemeanor is considered hate or bias motivated if hate motivation is an element of the crime, or if the conviction includes a hate crime sentence enhancement. (An element is something that needs to be proven in order to convict someone of a crime.) The protected characteristics under the Act are actual or perceived race, color, religion, national origin, gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, and disability.[↩]