The Devastating Toll of Gun Violence on American Women and Girls

More than 6,000 women die from gun violence every year—and women of color are disproportionately impacted.

Introduction

In many ways, men have historically been the focus of conversations about guns and gun violence in the United States. Nearly two-thirds of gun owners are male.1 Eighty-six percent of gun deaths in the US involve men, and men are six times more likely to die from gun violence than women.2

However, gun violence also takes a grueling and devastating toll on women, with women of color experiencing a particularly disproportionate impact. Each year, more than 6,000 women die from gun violence.3 More than half of these deaths are gun suicides,4 and women are also heavily impacted by the deadly intersection of guns and domestic violence, which claims hundreds of lives each year.5 Thousands more women are left in the wake of gun violence’s trauma, forced to grieve and recover from the loss of the many sons, husbands, brothers, and fathers who die as a result of gun violence.

The toll of gun violence on women in the US is particularly stark when compared to peer nations: compared to women in other high-income countries, US women are 21 times more likely to die from gun violence.6

It is clear that gun violence is an issue with deep, multi-faceted impacts on women’s safety, health, and well-being. Understanding this burden is essential to creating and implementing responsive solutions that will protect women, their families, and their communities.

MEDIA REQUESTS

Our experts can speak to the full spectrum of gun violence prevention issues. Have a question? Email us at media@giffords.org.

Contact

Gun Suicide

Each year, an average of more than 3,250 women die by firearm suicide, representing 54% of all gun deaths among women.7 Like firearm suicide rates overall, gun suicide rates among women are on the rise. In the last decade, the gun suicide rate rose 17% for women.8 These increases were larger for women of color. In fact, while gun suicide rates rose just 15% for white women, increases were much sharper for American Indian and Alaska Native women (114%), Black women (103%), Hispanic women (96%) and Asian American and Pacific Islander women (26%).9

Research also suggests that the rise in suicides among women is concentrated, in part, among young women and girls. A survey from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found that more than one in four teen girls reported they seriously considered attempting suicide, and more than one in 10 teen girls reported they attempted suicide in the past year.10 This research also found that teenage girls are experiencing high levels of hopelessness, sexual violence, and alcohol use—each of which is associated with elevated suicide risk.11 Alarmingly, gun suicide rates among girls aged 10 to 17 have risen 79% in the past decade, compared to a 74% increase among boys of the same ages.12 Similar trends are mirrored for 18 to 24-year-old women, who saw a 67% increase in gun suicides in the last decade.13

Unlike suicides among men, suicides among women have historically involved means other than guns. In fact, from 2012 to 2021, 57% of suicides among men were firearm suicides, compared to just 32% of suicides among women.14 However, this dynamic appears to be changing, with women increasingly using firearms in suicide attempts. In 2012, 31% of suicides among women were gun suicides; by 2021, this number had risen to 35%.15

The rise in firearm use in suicides and the increased firearm suicide rate may be explained, in part, by the broader access that women have to firearms in the home. Historically, a smaller proportion of women have owned firearms as compared to men.16 Recent research, however, suggests that women are increasingly purchasing firearms and becoming gun owners, which is partly attributable to the increased gun lobby marketing of firearms to women under the false pretense of protection.17 Approximately half of people who became new gun owners between January 2019 and April 2021 were women.18 Numerous studies show that firearm ownership and access are associated with an increased risk of suicide.19 In fact, one study found that women who own handguns are more than 35 times more likely than women who do not own handguns to kill themselves with a gun.20

Finally, it is important to note that despite these alarming trends, the vast majority of firearm suicide prevention programs in this country are predominantly tailored to the needs and experiences of men.21 It is critical that gun suicide prevention programs, including those that advocate for secure firearm storage and temporary relinquishment of firearms during times of crisis, are designed so as to take into account the needs and messages most salient for women.

Gun Homicide

In 2020, the US saw an unprecedented spike in assaultive gun violence. In fact, 2020 saw a 35% increase in gun homicide rates—the largest one-year increase on record.22 These increases continued in 2021, and were felt across nearly every age, racial and ethnic group, and geography.23

However, evidence suggests that these increases were particularly pronounced for women. While gun homicides rose 44% for men from 2019 to 2021, women experienced a 49% increase.24 Women of color saw an even more disproportionate burden: gun homicides increased 27% for white women, while Black women experienced a 78% increase.25

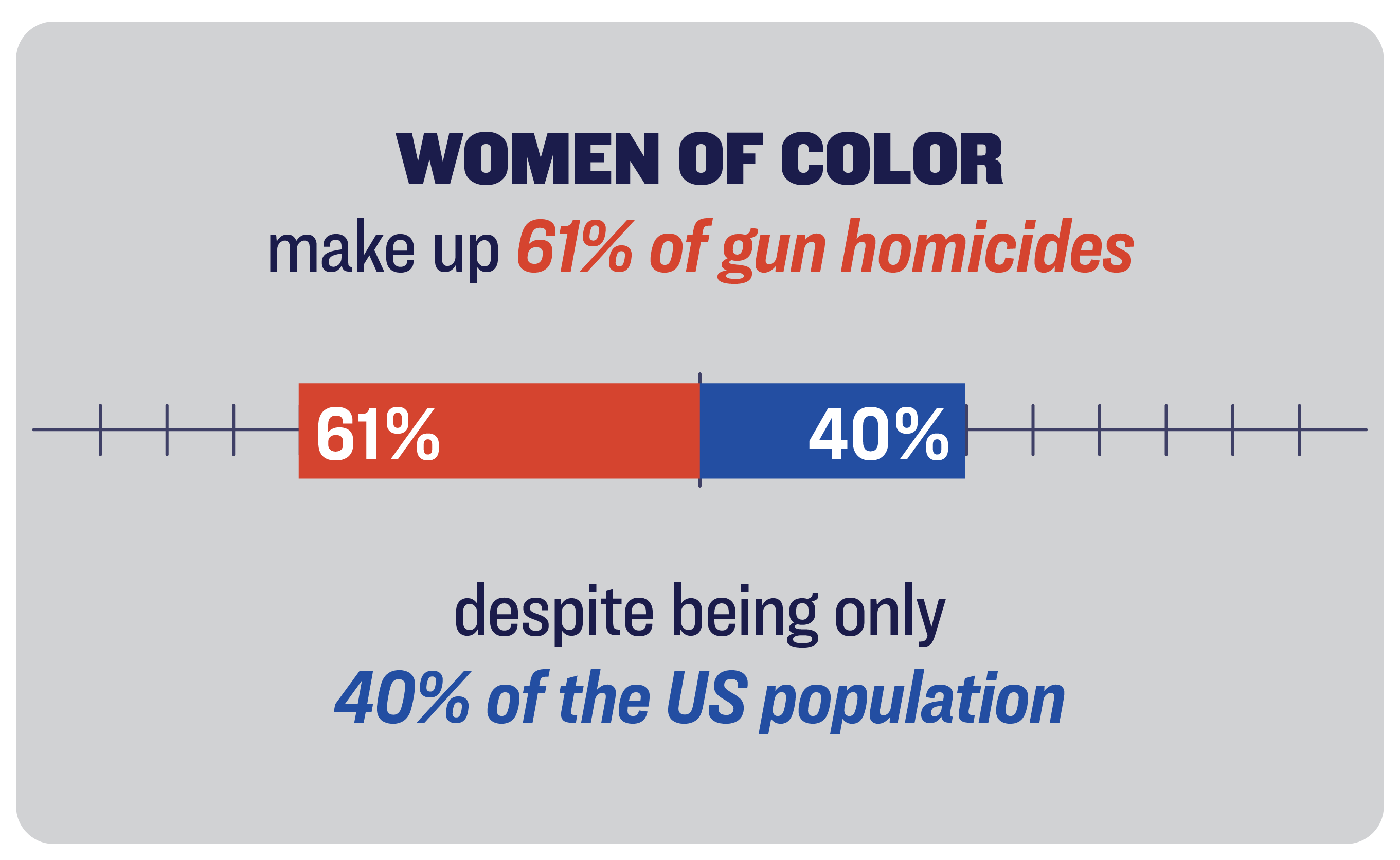

Each year, more than 2,600 women die in gun homicides.26Women of color make up 61% of these deaths, despite comprising less than 40% of the US population.27 In particular, Black and American Indian/Alaska Native Women are approximately five and three times as likely, respectively, to be killed in gun homicides compared to white women.28

Although women are impacted by many forms of gun homicide, they bear a disproportionate burden of the deadly intersection of firearms and domestic violence in particular. More than two-thirds of all intimate partner homicides of women are committed with guns.29 In 2020, more than 700 women were killed in firearm-related intimate partner homicides, most often by male intimate partners.30

Guns play a critical role in fueling lethal domestic violence. When a gun is present in the home where there is a domestic violence situation, a woman is five times more likely to be killed.31 One study found that cohabitants of California handgun owners were killed at home by a spouse or an intimate partner at more than seven times the rate of people who did not cohabitate with a handgun owner.32

Critically, while this deadly intersection impacts all women, women of color bear an even higher burden. American Indian and Alaska Native women and Black women are killed in firearm intimate partner homicides at two and three times the rate of white women, respectively.33

Domestic Violence

The combination of intimate partner violence and access to guns is an especially deadly mix.

Research also suggests that other marginalized and vulnerable women experience a disproportionate impact of firearm-related intimate partner violence. For example, homicide is a leading cause of death for pregnant and postpartum women—outpacing deaths from hypertensive disorders, hemorrhage, and sepsis—and firearms are involved in nearly 70% of homicide deaths among this population.34 Women with disabilities are also significantly more likely to experience domestic violence, including psychological aggression and stalking by an intimate partner, than women without disabilities.35

The consequences of firearm intimate partner violence extend, however, beyond just deaths. A recent study found that roughly one in seven women had experienced nonfatal abuse with a firearm by an intimate partner, including being shot at or threatened with a firearm.36 Research suggests that women who experience intimate partner abuse with a firearm are significantly more likely to experience severe PTSD symptoms, compared to women who experience abuse that does not involve firearms.37

Gun Violence–Related Trauma

Although women die from gun violence at lower rates than men, women—particularly women of color—disproportionately bear the social, psychological, and financial burden of gun violence survivorship. Too often, women are left to grieve and recover from the loss of their loved ones to gun homicide and gun suicide.

Mothers who lose children in homicides experience an incredibly devastating and debilitating psychological trauma. Studies show that parents whose children are murdered experience elevated levels of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), major depressive disorder (MDD), and other adverse mental health outcomes.38In fact, researchers who study community violence describe how Black mothers experience what they call a “living death” or a “second killing” in living with the trauma wrought by gun homicides.39 Importantly, these traumas can be compounded for women of color who face other systemic inequalities after the loss of a child, including feeling that their child’s death is treated as less worthy by the media and police investigators.40

Studies also suggest that mothers bereaved by the loss of a child to suicide can experience significant impairments to their mental and physical health.41 The loss of a loved one to suicide can leave family members with a distorted sense of responsibility for the death, feelings of being blamed, and social stigmatization.42

These traumatic impacts alone can be debilitating, but this unique trauma is often accompanied by further stressors. For example, women bereaved by gun violence are frequently left to settle the financial affairs of their lost loved one.43 Women who lose a partner to gun violence in many cases must contend with the loss of this partner’s income.44 These stressors can amplify trauma and its deleterious effects.

For women raising children in neighborhoods that experience disproportionately high rates of gun violence, the toll of chronic exposure to gun violence can also have adverse impacts on their mental health and the well-being of their families. One recent study shows that compared to mothers who have not witnessed gun violence, mothers who witness at least one shooting in their neighborhoods or local communities are up to 60% more likely to meet criteria for depression and to show more physical manifestations of depression symptoms.45

These pernicious impacts are felt not just by mothers, but by their entire families: maternal depression has been shown to have short and long-term associations with behavioral problems and depression among their children.46 In other words, the consequences of gun violence exposure and the trauma it creates can persist over generations.

GET THE FACTS

Gun violence is a complex problem, and while there’s no one-size-fits-all solution, we must act. Our reports bring you the latest cutting-edge research and analysis about strategies to end our country’s gun violence crisis at every level.

Learn More

Solutions

The toll of gun violence against women and communities writ large is devastating, but we know that it is also preventable. There are a number of policies that can help keep women and their loved ones safe from gun violence and its trauma, including:

- Comprehensive background checks through firearm licensing. Background checks help prevent people at significant risk of both gun suicide and domestic abuse from accessing firearms, yet federal law does not require a background check to be performed before every sale of a gun, including sales by unlicensed, private sellers. For example, one in 13 background check denials are connected to a disqualifying history of domestic abuse.47 States that have closed this loophole through a purchaser licensing system have seen dramatic reductions in gun homicides and gun suicides.48

- Gun suicide prevention policies like waiting periods, extreme risk protection order laws, and safe storage laws. Laws like these are proven to help prevent suicides. One study found that waiting period laws may reduce suicide rates by up to 11%, and extreme risk laws in Connecticut and Indiana have been associated with 14% and 7.5% reductions, respectively, in gun suicides in these states.49

- Stronger domestic violence laws. These laws can help keep guns out of the hands of abusive partners and are associated with reductions in both overall and firearm-involved intimate partner homicides. In fact, states that restrict access to guns by people subject to active domestic violence restraining orders (DVROs) have seen a 13% reduction in intimate partner homicides involving firearms, with reductions of up to 16% observed when states require proof of firearm relinquishment for DVROs.50

- Investments in community violence prevention programs. By helping prevent community gun violence, we can help protect women from the trauma it brings. These programs can involve a variety of strategies to reach out to those involved in gun violence in their communities, build relationships and provide supportive social services, address conflict through nonviolent means like de-escalation and mediation, and work to support community healing from violence. Research suggests these programs are associated with substantial reductions in gun homicides and shootings.51

Various federal and state policies are designed to address the toll of gun violence on women and the lethality of firearms in suicide and domestic violence situations. In 2022, Congress passed the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act (BSCA), which includes provisions to address firearm suicide, community violence, and domestic violence. This law provides funding for the implementation of extreme risk protection order laws and other crisis intervention services to help prevent gun suicides, as well as $250 million to support community violence intervention strategies. Additionally, the BSCA addresses a loophole in federal law that allows abusive dating partners with domestic violence misdemeanor convictions to access guns.

Federal law has also specifically addressed the role of firearms in domestic violence since the mid-1990s. The Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) includes support for the implementation of domestic violence prohibitions in both the criminal and civil contexts. This legislation is renewed by Congress every five years, providing opportunity for its existing protections to grow to better protect survivors and their needs. In 2022, the reauthorization of VAWA included the NICS Denial Notification Act of 2022, which requires the US attorney general to notify local law enforcement whenever a person, including someone convicted of a misdemeanor crime of domestic violence or subject to a domestic violence protection order, fails a NICS background check to buy a gun. Continuing to strengthen and develop a comprehensive approach to preventing gun violence against women is crucial to addressing the devastating toll it enacts.

In addition to laws and programs that prevent gun violence, policies which address the unique needs of gun violence survivors can also play an important role in addressing the burden of gun violence on women. Women surviving gun violence face a number of unique challenges, with survivorship often impacting mental health, financial well-being, and individual safety. It is critical that people who have lost loved ones to gun violence have access to assistance to help cope with trauma wrought by gun violence—and that there are policies in place to ensure people can easily access these resources.

Conclusion

Women have long been at the forefront of the movement to end gun violence in America, with gun safety advocacy becoming a salient feature of survivorship for so many women.52 We’ve seen this in the countless mothers who have turned the pain of losing their child into a movement to protect others. And in women like Gabby Giffords, who knows the consequences of our gun violence epidemic all too well. Women across the country from so many walks of life—Republicans, Democrats, and gun owners alike—support stronger gun laws that would protect them and their families.53

Despite these efforts, too many women are dying from gun violence or being forced to learn how to live with its devastation. Our women, our families, and our nation deserve better. We know that gun safety laws can keep firearms away from abusive partners, prevent gun suicides, and protect our communities from the trauma of gun violence. These solutions can save lives—but only if our leaders have the courage to pass and implement them.

Special thanks to Julia Weber for her review of and comments on this report.

REPORT

10 YEARS of COURAGE

Since founding Giffords in the wake of the Sandy Hook shooting, we’ve helped pass a remarkable 525 significant gun safety laws in 49 states.

Learn More- Matthew Miller, Wilson Zhang, and Deborah Azrael, “Firearm Purchasing During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Results from the 2021 National Firearms Survey,” Annals of Internal Medicine 175, no. 2 (2022): 219–225.[↩]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (WONDER), “Underlying Cause of Death, 2018-2021, Bridged Race” last accessed March 23, 2023, https://wonder.cdc.gov/.[↩]

- Id.[↩]

- Id.[↩]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS), “WISQARS National Violent Death Reporting System,” last accessed March 24, 2023, https://wisqars.cdc.gov/nvdrs/.[↩]

- Erin Grinshteyn and David Hemenway, “Violent Death Rates in the US Compared to Those of the Other High-income Countries, 2015,” Preventive Medicine 123 (2019): 20–26.[↩]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (WONDER), “Underlying Cause of Death, 2018-2021, Bridged Race” last accessed March 23, 2023, https://wonder.cdc.gov/.[↩]

- Id.[↩]

- Id.[↩]

- “Youth Risk Behavior Survey: Data Summary & Trends Report, 2011-2021,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for HIV, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, February 13, 2023, https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/pdf/YRBS_Data-Summary-Trends_Report2023_508.pdf.[↩]

- Id.[↩]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (WONDER), “Underlying Cause of Death, 2018-2021, Bridged Race” last accessed March 23, 2023, https://wonder.cdc.gov/.[↩]

- Id.[↩]

- Id.[↩]

- Id.[↩]

- Id.[↩]

- Laura Finley and Luigi Esposito, “Campaign of Fear and Consumption: Problematizing Gender-based Marketing of Weapons,” Contemporary Justice Review 22, no. 2 (2019): 157–170; Elizabeth M. Blair and Eva M. Hyatt, “The Marketing of Guns to Women: Factors Influencing Gun-related Attitudes and Gun Ownership by Women,” Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 14, no. 1 (1995): 117–127.[↩]

- Matthew Miller, Wilson Zhang, and Deborah Azrael, “Firearm Purchasing During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Results from the 2021 National Firearms Survey,” Annals of Internal Medicine 175, no. 2 (2022): 219–225.[↩]

- Andrew Anglemyer, Tara Horvath, and George Rutherford, “The Accessibility of Firearms and Risk for Suicide and Homicide Victimization Among Household Members: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis,” Annals of Internal Medicine 160, no. 2 (2014): 101–110; Matthew Miller et al., “Firearms and Suicide in the United States: is Risk Independent of Underlying Suicidal Behavior?,” American Journal of Epidemiology 178, no. 6 (2013): 946–955.[↩]

- David M. Studdert et al., “Handgun Ownership and Suicide in California,” New England Journal of Medicine 382, no. 23 (2020): 2220–2229.[↩]

- Talia L. Spark et al., “Firearm Lethal Means Counseling Among Women: Clinical and Research Considerations and a Call to Action,” Current Treatment Options in Psychiatry 9, no. 3 (2022): 301–311.[↩]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (WONDER), “Underlying Cause of Death, 2018-2021, Bridged Race,” last accessed March 23, 2023, https://wonder.cdc.gov/. See also, Kelly Drane, “Surging Gun Violence: Where We Are, How We Got Here, and Where We Go Next,” Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence, May 4, 2022, https://giffords.org/lawcenter/report/surging-gun-violence-where-we-are-how-we-got-here-and-where-we-go/.[↩]

- Id.[↩]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (WONDER), “Underlying Cause of Death, 2018-2021, Bridged Race” last accessed March 23, 2023, https://wonder.cdc.gov/.[↩]

- Id.[↩]

- Id.[↩]

- Id.[↩]

- Id.[↩]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS), “WISQARS National Violent Death Reporting System,” last accessed March 24, 2023, https://wisqars.cdc.gov/nvdrs/.[↩]

- Id.[↩]

- Jacquelyn C. Campbell et al., “Risk Factors for Femicide in Abusive Relationships: Results From a Multisite Case Control Study,” American Journal of Public Health 93, no. 7 (2003): 1089–1097.[↩]

- David M. Studdert et al., “Homicide Deaths Among Adult Cohabitants of Handgun Owners in California, 2004 to 2016: a Cohort Study,” Annals of Internal Medicine 175, no. 6 (2022): 804–811.[↩]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS), “WISQARS National Violent Death Reporting System,” last accessed March 24, 2023, https://wisqars.cdc.gov/nvdrs/.[↩]

- Maeve E. Wallace, “Trends in Pregnancy-associated Homicide, United States, 2020,” American Journal of Public Health 112, no. 9 (2022): 1333–1336; Anna M. Modest, Laura C. Prater, and Naima T. Joseph, “Pregnancy-associated Homicide and Suicide: An Analysis of the National Violent Death Reporting System, 2008–2019,” Obstetrics & Gynecology 140, no. 4 (2022): 565–573.[↩]

- Matthew J. Breiding and Brian S. Armour, “The Association Between Disability and Intimate Partner Violence in the United States,” Annals of Epidemiology 25, no. 6 (2015): 455–457.[↩]

- Avanti Adhia et al., “Nonfatal Use of Firearms in Intimate Partner Violence: Results of a National Survey,” Preventive Medicine 147 (2021).[↩]

- Tami P. Sullivan and Nicole H. Weiss, “Is Firearm Threat in Intimate Relationships Associated with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms Among Women?,” Violence and Gender 4, no. 2 (2017): 31–36.[↩]

- Alyssa A. Rheingold and Joah L. Williams, “Survivors of Homicide: Mental Health Outcomes, Social Support, and Service Use Among a Community-based Sample,” Violence and Victims 30, no. 5 (2015): 870–883.[↩]

- Brooklynn Hitchens, “Second Killings: The Black Women and Girls Left Behind to Grieve America’s Growing Gun Violence Crisis,” SUNY Rockefeller Institute of Government, July 26, 2022, https://rockinst.org/blog/second-killings-the-black-women-and-girls-left-behind-to-grieve-americas-growing-gun-violence-crisis/.[↩]

- Annette Bailey et al., “Black Mothers’ Cognitive Process of Finding Meaning and Building Resilience After Loss of a Child to Gun Violence,” British Journal of Social Work 43, no. 2 (2013): 336–354.[↩]

- Victoria Ross et al., “Parents’ Experiences of Suicide-bereavement: A Qualitative Study at 6 and 12 Months After Loss,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15, no. 4 (2018): 618; James M. Bolton et al., “Parents Bereaved by Offspring Suicide: a Population-based Longitudinal Case-control Study,” JAMA Psychiatry 70, no. 2 (2013): 158–167; Alexandra Pitman et al., “Effects of Suicide Bereavement on Mental Health and Suicide Risk,” The Lancet Psychiatry 1, no. 1 (2014): 86–94.[↩]

- Franz Hanschmidt et al., “The Stigma of Suicide Survivorship and Related Consequences—A Systematic Review,” PloS One 11, no. 9 (2016).[↩]

- Brooklynn Hitchens, “Second Killings: The Black Women and Girls Left Behind to Grieve America’s Growing Gun Violence Crisis,” SUNY Rockefeller Institute of Government, July 26, 2022, https://rockinst.org/blog/second-killings-the-black-women-and-girls-left-behind-to-grieve-americas-growing-gun-violence-crisis/.[↩]

- Anne Corden, Michael Hirst, and Katharine Nice, “Death of a Partner: Financial Implications and Experience of Loss,” Bereavement Care 29, no. 1 (2010): 23–28.[↩]

- Christine Leibbrand, Frederick Rivara, and Ali Rowhani-Rahbar, “Gun Violence Exposure and Experiences of Depression Among Mothers,” Prevention Science 22 (2021): 523–533.[↩]

- Sherryl H. Goodman et al., “Maternal Depression and Child Psychopathology: A Meta-analytic Review,” Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review 14 (2011): 1-27; Daniel M. Bagner et al., “Effect of Maternal Depression on Child Behavior: a Sensitive Period?,” Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 49, no. 7 (2010): 699–707.[↩]

- Connor Brooks et al., “Background Checks for Firearm Transfers, 2016-2017, Bureau of Justice Statistics Bulletin 5,” US Department of Justice: Bureau of Justice Statistics, February 2021, https://bjs.ojp.gov/library/publications/background-checks-firearm-transfers-2016-2017.[↩]

- Alexander D. McCourt et al, “Purchaser Licensing, Point-of-Sale Background Check Laws, and Firearm Homicide and Suicide in 4 US States, 1985–2017,” American Journal of Public Health 110, no. 10 (2020): 1546–1552.[↩]

- Aaron J. Kivisto and Peter Lee Phalen, “Effects of Risk–based Firearm Seizure Laws in Connecticut and Indiana on Suicide Rates, 1981–2015,” Psychiatric Services 69, no. 8 (2018): 855–862.[↩]

- April M. Zeoli et al., “Analysis of the Strength of Legal Firearms Restrictions for Perpetrators of Domestic Violence and Their Association with Intimate Partner Homicide,” American Journal of Epidemiology 187, no. 11 (2018).[↩]

- See, e.g., “Intervention Strategies,” Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence, last accessed September 11, 2023, https://giffords.org/lawcenter/gun-laws/policy-areas/other-laws-policies/intervention-strategies/.[↩]

- See, e.g., Brooklynn K. Hitchens, Ann M. Aviles, and Kathleen McCallops, “Mothering in the Streets: Familial Adaptation Strategies of Street‐identified Black American Mothers,” Journal of Marriage and Family 84, no. 5 (2022): 1270–1290.[↩]

- Cassandra K. Crifasi et al., “Differences in Public Support for Gun Policies Between Women and Men,” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 60, no. 1 (2021): e9–e14.[↩]