¿Qué es intervención de violencia en la comunidad?

Jul 25, 2023

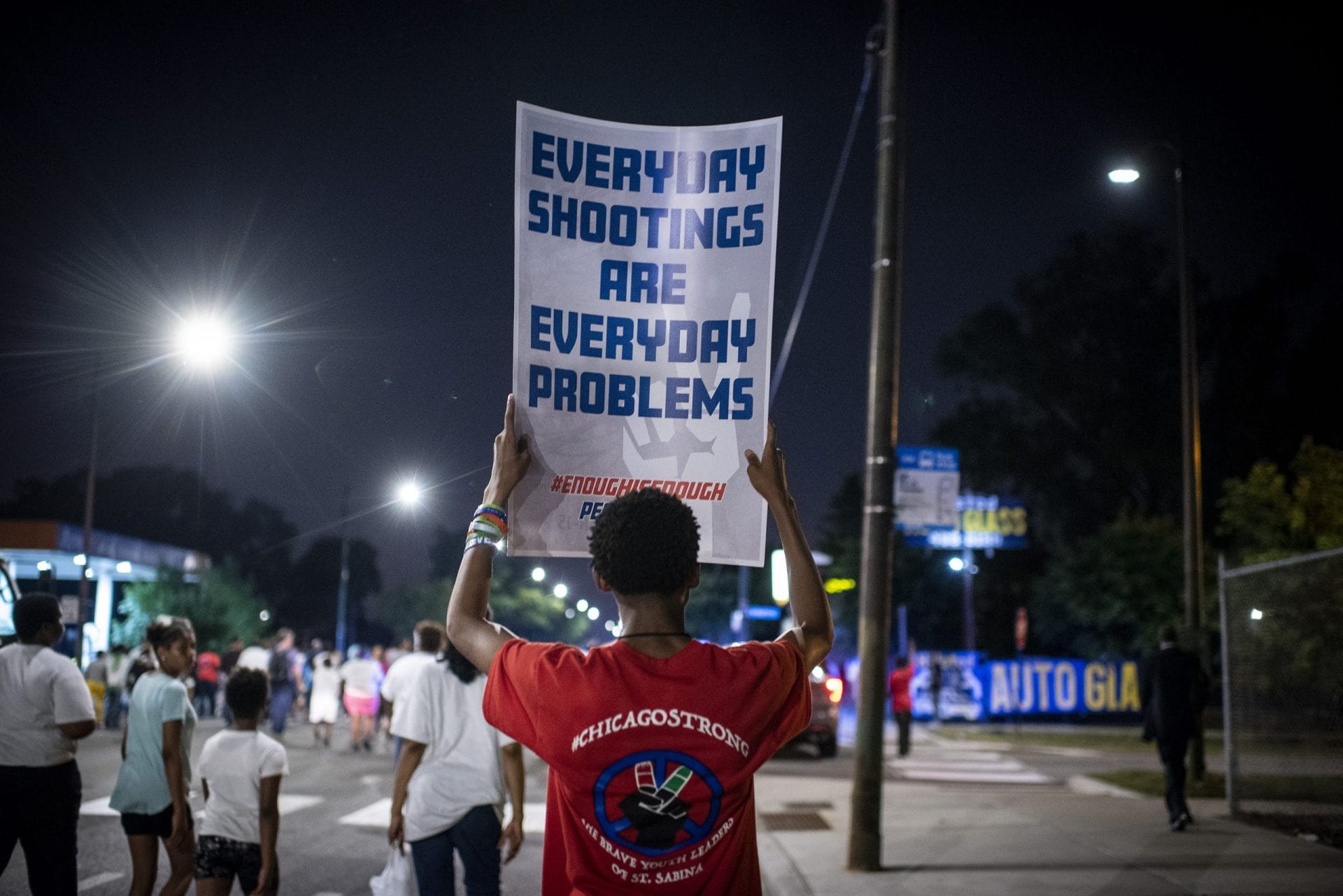

All too often, community violence—and some of its most successful solutions—fail to factor into the policy debate about public safety.

Over the last few years, the nation experienced a deadly surge in gun violence. In 2020, we saw the largest single-year increase in gun homicides on record, followed by a peak in gun deaths in 2021.1 While violence remains at elevated levels, provisional data from the CDC suggests that this alarming trend may be reversing course.

In 2022, firearm-related deaths declined modestly for the first time since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, and data from 2023 indicates further reductions. Though cause for optimism, gun violence continues to devastate far too many lives. Over 46,000 people were killed with guns in 2023, averaging nearly 128 gun deaths per day. At least twice as many people were shot and survived.2

Community violence, one of the most prevalent drivers of the gun violence epidemic, is defined by the CDC as violence between “unrelated individuals, who may or may not know each other, generally outside the home.”3 This includes homicides, shootings, stabbings, and physical assaults.

In 2022, over 19,600 lives were taken by homicide—nearly 80% of which involved firearms—and tens of thousands more were injured severely enough to require hospitalization.4 Today, gun violence is the leading cause of death for children and adolescents.5

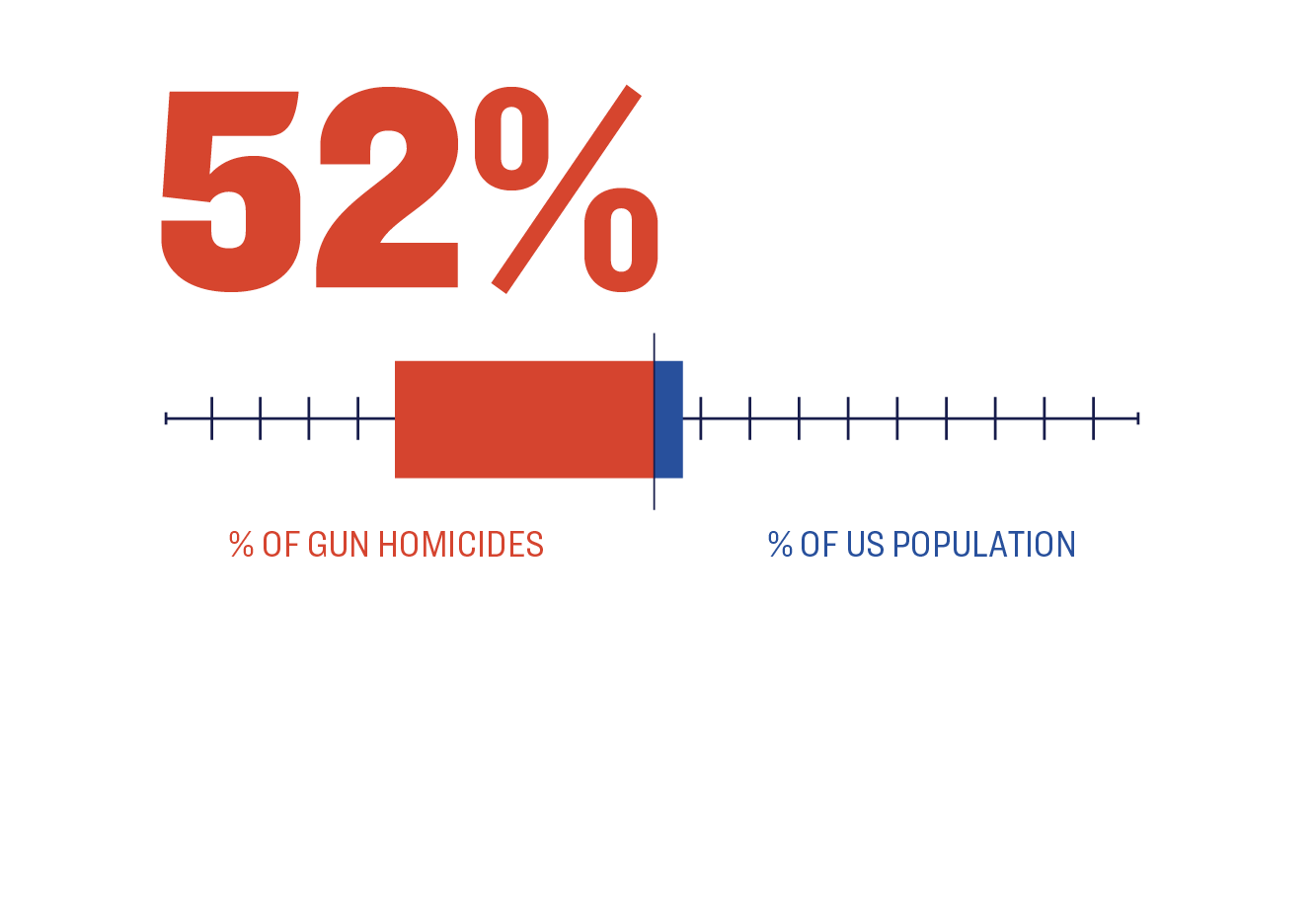

The burden of community violence tends to fall hardest on Black and Latino residents, who are disproportionately impacted. Despite making up less than a third of the US population, these groups account for more than three-quarters of gun homicide victims in the US.6 These disparities are further exacerbated by a historical lack of investment, which puts communities of color in a position where they are far too under-resourced to address the magnitude of these issues without a concerted attempt to support their efforts.

Community violence intervention (CVI) refers to a set of non-punitive, community-led strategies that are designed to interrupt the transmission of violence by engaging those at highest risk through the provision of individually tailored support services.

Source

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (WONDER), “Underlying Cause of Death, 2018-2023, Single Race,” last accessed February 3, 2025, https://wonder.cdc.gov/.

Commonly referred to as “CVI workers,” the experts who practice this intervention draw from their lived experiences to reduce the spread of violence in their own community by engaging those at highest risk of being injured and/or producing violence. People at high risk often have prior contact with the criminal legal system, have been shot or seriously injured, and may have a history of carry firearms, though a number of other factors may also contribute. 7

There are essentially two core components to community violence intervention.8 Both require training and a commitment to professional standards of practice.9 Each is incomplete without the other:

Community violence intervention workers put their lives on the line every day to save other people. This critically important work is also extremely dangerous. Together with our partners, we’re asking for long-term, sustainable funding for community violence intervention to ensure that these individuals can do their jobs safely and effectively.

Read MoreCVI workers are members of an affected community who are committed to promoting peace and safety and trained to leverage their relationships and engage those at highest risk of involvement in violence to prevent potential injury or death.

For as long as there has been community violence, there have been homegrown peacemakers. They can include concerned community members, parents, faith-based leaders, civil rights activists, previously incarcerated individuals, and survivors of violence who have risked their lives to save others. CVI workers leverage their credibility to develop relationships with community members and groups that might cause violence with the goal of preventing its spread and building peace in a community; they are not responsible for enforcing the law.

Community violence intervention is a crucial approach to fighting gun violence. Keep up to date on the latest CVI legislation in your state with the Giffords Community Violence Intervention Policy Analysis & Tracking Hub—CVI-PATH.

Read MoreCVI work can take place in a variety of settings. Listed below are a few models of community violence interventions:

Hospital-Based Violence Intervention Programs14 are built on the premise that experiencing violence is a significant risk factor for future exposure to violence.15 These programs engage victims of violence at the bedside and work with them post-discharge to decrease the likelihood of reinjury or retaliation. This approach has been shown to stop the revolving door of violent injury seen in too many American hospitals and trauma centers.16

Street Outreach and Violence Interruption17 are proactive approaches that employ trained workers to identify and mediate conflicts in their community. These strategies work to prevent violence before it happens and de-escalate conflict before it potentially turns fatal. Evaluations of street outreach programs from across the county credit this type of work with double-digit reductions in violence in cities large and small.18

Case Management and Transformational Mentoring Programs19 function to provide individuals impacted by community violence with the appropriate social service supports that are tailored to their needs. In some cases, this may look like developing an individualized service plan that incorporates cognitive behavioral therapy, mentoring or life coaching by a trained professional, or helping an individual apply for jobs or legal documents, among other services that function to utilize strategies and protocols that curb the perpetuation of community violence.

No singular CVI approach is going to eliminate community violence; rather, the success of a CVI strategy is only as strong as its coordinated community networks. Effective CVI efforts are those that draw from a menu of approaches, utilize different touchpoints to recruit participants in need, and provide wraparound services through a comprehensive strategy that engages local governments and community organizations.

Local governments are best positioned to support comprehensive CVI strategies by providing sustainable funding and resources to programs that offer those at highest risk the opportunity to explore alternatives to engaging in violent activities.

Since 2007, Los Angeles’s Office of Gang Reduction and Youth Development (GRYD) has implemented a coordinated, city-funded gang reduction strategy that consists of an array of components including: violence prevention, intervention, interruption, and community engagement. This comprehensive approach has been associated with approximately 27 less retaliatory gang homicides and 87 less retaliatory gang aggravated assaults per year.20 Even after recent increases in violence in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, Los Angeles homicides are still down more than 20% from their average level in the years prior to the implementation of GRYD.21

In Massachusetts, which has the lowest gun death rate of any state,22 the Executive Office of Health and Human Services operates the Safe and Successful Youth Initiative (SSYI) in 21 communities throughout the state. SSYI offers young men who have committed a gun or gang-related crime services that include case management, employment support, and behavioral health services, and it is associated with reducing violent crime in the state by preventing more than 800 violent crime victimizations per year.23Gun-related homicides decreased more than 20% in the nine years following SSYI implementation.24

The gun violence prevention field is evolving rapidly to support CVI efforts led by communities of color. However, there are other strategies to combat community violence, some of which involve law enforcement. Below are two commonly referenced approaches:

Group Violence Intervention, or “Focused Deterrence,” calls for a local partnership of law enforcement, service providers, and community members to work collectively to identify potential producers of violence and bring them together to intervene with a message that the violence must stop.25 Partners offer participants social services while narrow enforcement actions are taken against those who continue to engage in acts of serious violence.

Environmental Crime Prevention focuses on improving the physical environment in high-crime neighborhoods, including cleaning up abandoned lots and installing lighting in dark areas that serve as magnets for violent crime.26 It also includes Safe Passage programs, in which schools, law enforcement, and communities collaborate to provide safe routes to and from school.

It cannot be emphasized enough that Black and Brown communities experience the harm and trauma of community violence at alarmingly high rates. As such, in order to be effective, efforts to reduce violence must be culturally competent in nature.

While historically, the distribution of funding and other government resources to reduce community violence has strongly favored law enforcement efforts, a comprehensive public safety strategy must provide adequate support to community-led programs that have a proven track record of reducing violence.

In the last year, the federal government has recognized the power and impact of community-based approaches and has instructed agencies to consult with communities that have been historically underrepresented, underserved by, or subject to discrimination by federal policies and programs. This action aids in ensuring that CBOs closest to the most impacted populations are able to access the resources they need to provide support to their communities.

The cost to scale up and support lifesaving community violence intervention strategies is a fraction of what gun violence costs taxpayers.

Although not all communities experience high rates of gun violence, all Americans bear the significant economic burden stemming from health care, law enforcement, and the other tremendous public expenses associated with community violence. Gun violence costs this country over $557 billion every year, and most of these costs are shouldered by the American taxpayer. A single gun fatality costs taxpayers $270,904. On average, each resident pays nearly $1,700 annually because of gun violence.27

Evidence shows that investing in community violence intervention programs both saves lives and reduces the enormous economic burdens of violence: 28

Historically, Congress has prioritized appropriating billions of dollars to support law enforcement, with a heavy emphasis on funds to hire law enforcement personnel, rather than invest significantly in CVI-focused efforts. Fiscal Year 2022 marked the first time Congress established a dedicated grant program within the Department of Justice specifically to support CVI efforts by creating the Community Violence Intervention and Prevention Initiative (CVIPI).32 However, CVIPI was only appropriated $50 million for Fiscal Year 2022, an amount that fails to meet the needs of the field or match the heightened levels of violence experienced across communities.

Through executive action, the Biden administration has made clear that the federal government should seek to address systemic barriers to opportunities and benefits for people of color.33 More specifically, the administration has taken concrete steps to encourage increased investment in “community violence interventions—evidence-based programs that are shown to help reduce violent crime.”34

By rectifying a lack of investment in community-based violence reduction programming, Congress can make meaningful strides towards achieving this goal. An annual $750 million federal investment in CVI, split evenly between DOJ and HHS, would help to fill the glaring gap in national public safety policy, allowing dozens of US cities most impacted by violence to replicate the transformative CVI strategies and approaches discussed above.

This funding would enable the hiring of hundreds more trained street outreach workers and other types of violence prevention professionals working on the ground in communities to disrupt cycles of violence and provide a proactive, coordinated health response, in order to fill gaps in the traditional law enforcement response to violence and improve public safety.35

As we’ve seen at the state and city level, supporting the implementation and expansion of CVI strategies is a long-overdue investment in an effective, comprehensive approach to public safety that will pay for itself many times over. This is an investment supported by the Biden administration,36 as well as national coalitions of practitioners, advocates, researchers, and local political leaders.37 As the nation seeks to address centuries of divestment from Black and Brown communities, Congress must lend greater support to proven and promising CVI strategies working to heal those most impacted by violence and prioritize investments in community violence intervention.

Community violence intervention focuses on reducing the daily homicides and shootings that contribute to our country’s gun violence epidemic. We created Giffords Center for Violence Intervention to champion community-based efforts to save lives and improve public safety.

Read More

Interventions are most effective when they are supported by strong community networks. Sign up for Giffords Center for Violence Intervention’s newsletter to learn more about what’s happening in the field, relevant legislation, and funding opportunities.