Research Roundup

An Analysis of Gun Violence Publication Trends in 2021

Executive Summary

Each of these deaths takes an enormous toll on families and communities across our nation, and clearly, this problem isn’t going away on its own. It is more urgent than ever that we treat this crisis like the public health and safety issue it is and take concerted action to prevent gun violence.

Scientific research is a crucial component of a public health approach to gun violence prevention: understanding the causes of gun violence and the impacts of potential solutions helps us craft and implement the most effective policies to address this crisis. For too long, however, there has been insufficient scholarship on the issue, leaving too many gaps in our understanding of this epidemic and the effectiveness of potential solutions to combat it.

This report is a first-of-its-kind survey of the research landscape that seeks to identify trends in gun violence research publications in 2021, to better understand areas of current scientific attention, and to identify gaps that warrant further analysis—and additional resources—going forward.

Beginning in the 1990s, federal lawmakers essentially eliminated public funding for research on gun violence, and, in the ensuing decades, virtually no federal dollars were spent studying this issue.3 While some private funders continued to fund gun violence research, the consequences of the federal funding freeze were severe. A 2017 study found that gun violence research receives less than two percent of the federal funding it would be expected to receive based on the scope and toll of the problem.4 This study also found that the volume of research publications on gun mortality was just 4.5% of what would be expected based on publication volume for other leading causes of mortality.2

In recent years, there has been a resurgence of public monies for gun violence research. In 2019, with bipartisan support, Congress passed a funding bill appropriating $25 million for gun violence research, to be split between the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). These funds have already been used to fund nearly 50 new gun violence research projects and data collection efforts, the results of which will be released over the coming years.5 States have also stepped up to fill research gaps created by the lack of federal funding, with several states—California,6 New Jersey,7 and Washington8—establishing firearm violence research centers that operate with state funding.

Private research funding has also increased in recent years. For example, in 2018, Arnold Ventures provided $20 million to seed the National Collaborative on Gun Violence Research, which has since received additional funding from other donors.9 Since its creation, the collaborative has funded 44 gun violence research projects on topics including suicide, violent crime, school violence, officer-involved shootings, firearm safety, defensive gun use, and nonfatal firearm injuries.10 Additionally, between December 1993 and December 2018, the Joyce Foundation11 provided $32 million in grants for gun violence research, resulting in at least 240 peer-reviewed publications.12

This new funding is critical, but there are still decades of lost research to make up for. One recent report estimated that it will cost between $587 and $639 million over five years—or roughly $117 to $128 million annually—for the federal government to fully implement a comprehensive plan to close the gun violence information gap.13 We’ve seen promising steps to expand federally funded gun violence research, with President Biden requesting $50 million for Fiscal Year 2022 to support research at the CDC and NIH 14 and both the House and Senate appropriations bills including $50 million for this funding. At the time of publication of this report, negotiations to finalize the FY2022 appropriations legislation are ongoing in Congress.

With this new focus on gun violence research, stakeholders have made many calls for how and where funding should be spent. Starting in 2019, NORC at the University of Chicago began a project to evaluate gaps in gun violence data collection infrastructure.15 This project culminated in a report that included 13 action items for the federal government, including improving the timeliness of federal data and better tracking non-fatal firearm injuries.16 In 2020, the Joyce Foundation released a report outlining 100 key questions across 10 different issue areas that a comprehensive gun violence research agenda should address.17

These reports provide important information to guide research priorities in the gun violence prevention field, but it is also important to consider the focus of current scientific attention. To better understand the common topics and themes of gun violence related research in 2021, Giffords Law Center sought to comprehensively track, review, and qualitatively code every study published in peer-reviewed journals related to gun violence and gun policy. To our knowledge, this is the first analysis to comprehensively analyze trends in all gun violence-related research in a given year.

Given that peer-reviewed articles are a major means for dissemination of new research findings, analysis of these articles can help us assess commonalities in scientific attention in this field over the past year. Based on our review, we identified several areas that should be addressed within the field of gun violence research, including:

- Increasing overall funding for gun violence research

- Improving gun violence data collection

- Prioritizing gun violence prevention policy and program evaluations

- Publishing more responsive research

- Creating more community-research partnerships

- Making the field of research more accessible

Our hope is that this analysis can help researchers, funders, and policymakers better understand the current state of the gun violence research field and use these results to help guide actionable, equitable research as new funding streams continue to become available.

MEDIA REQUESTS

Our experts can speak to the full spectrum of gun violence prevention issues. Have a question? Email us at media@giffords.org.

Contact

Research articles for this analysis were identified using Google Scholar and PubMed alert systems. Search terms included firearm- and firearm violence-related terms (e.g. gun, firearm, gun violence, homicide, suicide, shooting) along with various terms related to specific gun violence prevention policies (e.g. universal background check, extreme risk protection order, stand your ground, violence intervention). Additional articles were identified through gun violence prevention related news sources, gun violence prevention organization newsletters, and direct contact with gun violence prevention researchers. Articles published in 2021 but identified after January 5, 2022 were not included in the analysis.

Our analysis considered articles that both (1) were published or made available in a peer-reviewed journal in 2021 and (2) provided novel scientific analysis related to the causes, consequences, characterization, or prevention of firearm violence and injury in the United States. Our analysis excluded non-empirical articles, including commentaries, review articles, and articles that only discussed theory without novel data analysis. Additionally, we excluded from our sample articles published in non-peer reviewed sources, including intramural federal and state government reports and articles. In our tracking, we identified several medical case studies of and studies focusing solely on non-US gun violence.18 We excluded these studies from final coding analysis given their limited applicability to population-based gun violence prevention efforts in the US.

Our final analytic sample consisted of 493 eligible articles. To systematically identify the topics and themes of these articles, we created a database, consisting of more than 60 fields pertaining to the type of gun violence covered in the article (homicide, suicide, etc.), the main area of focus of the article (gun violence, gun policy, gun violence prevention program, etc.), and other relevant characteristics including the types of risk factors evaluated, the geographic unit of analysis, and the methodology of the article. We then coded each article in the database.

Brief descriptions of some of the reviewed articles are included as examples within our analysis. These descriptions are not meant to summarize all research findings from the selected studies, and not all studies reviewed in our analysis were included as example studies.

HERE TO HELP

Interested in partnering with us to draft, enact, or implement lifesaving gun safety legislation in your community? Our attorneys provide free assistance to lawmakers, public officials, and advocates working toward solutions to the gun violence crisis.

CONTACT US

Types of Gun Violence Studied

Gun violence in the US takes many different forms—including gun suicides, gun homicides, police shootings, and unintentional shootings—and often impacts people differently based on who they are and where they live. Having actionable research on all types of gun violence is critical for understanding how we can address this issue in all its forms.

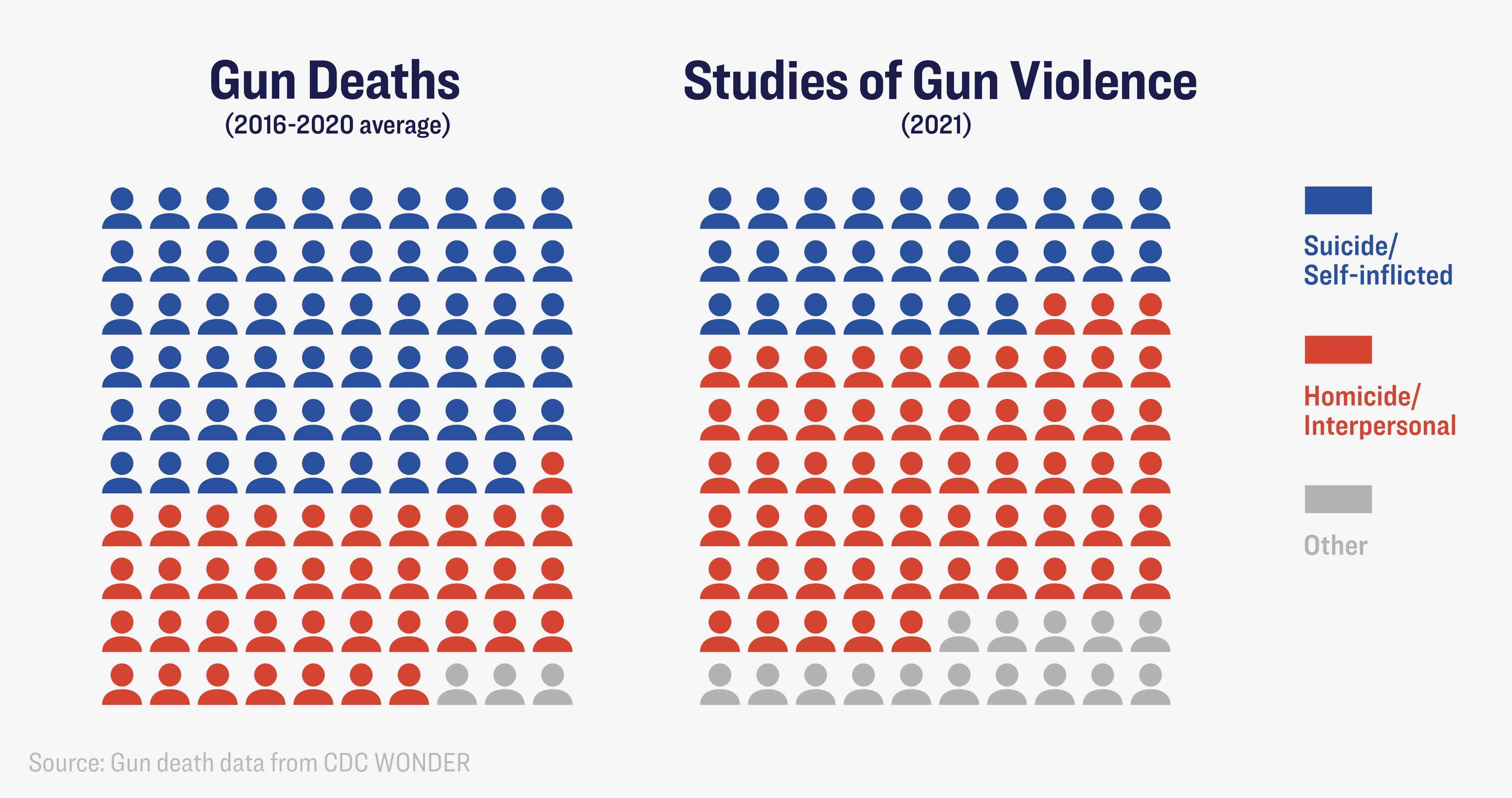

Many studies (78%) published in 2021 focused on or provided new data on at least one form of gun violence. Of these studies, 24% included the study of two or more forms of gun violence. The majority (58%) of studies that focused on at least one form of gun violence provided findings on interpersonal gun violence, including gun homicides and gun assaults.

Twenty-seven percent of articles provided specific focus on gun suicide—roughly half as many articles as those that provided specific focus on gun homicide, despite the fact that roughly three in five gun deaths in the US are gun suicides.19

Approximately 10% of articles focused on unintentional shootings. A relatively small number (6%) of studies focused on police shootings. Additionally, despite the fact that early data and anecdotal evidence suggests a rise in hate crimes and violent extremism in recent years,20 we identified almost no (less than 1%) US-based studies on hate crimes or violent extremism involving firearms.

Importantly, gun homicides also take multiple distinct forms, including community violence, domestic violence, and mass shootings. Our review found that of articles that provided specific study of gun homicides, a roughly equal number focused on mass shootings (29%) and community gun violence (29%), despite the fact that community violence accounts for a far greater percentage of gun deaths and injuries each year. A smaller number of articles focused on domestic violence (12%).

Scholarship on each form of gun violence is critical, as is evidenced by the new research findings from articles published in 2021. For example, studies about gun homicides and interpersonal gun violence included the following new findings:

- CDC researchers described the geographic distribution of gun homicides across the US, showing that while gun homicides are deeply concentrated and associated with poverty rates, both metro and non-metro areas experience high rates of firearm homicides.21

- Jason Silva compared completed, attempted, failed, and foiled mass shooting outcomes in the United States, noting that completed mass shootings were more likely than attacks stopped either before four victims were killed or before any victims were killed to involve individuals in possession of multiple guns.22

- Lisa Geller and colleagues examined the role of domestic violence in mass shootings, finding that 59% of mass shootings with four or more casualties from 2014 to 2019 were related to domestic violence.23

- TK Logan and Kelly Lynch examined intimate partner-related firearm threats among cohabitating and noncohabitating partners, finding no difference in the prevalence of firearm threats for victims who lived with their abusive partner compared to those who did not.24

- Researchers from several academic departments of surgery, including a scholar from the New Jersey Gun Violence Research Center, conducted a systematic review of research on community-based gun violence prevention efforts, ultimately making a recommendation supporting the implementation of community-based violence prevention programs.25

Among the research on firearm suicide were the following new findings:

- Catherine Barber and colleagues explored the frequency of suicides at gun ranges, finding that suicides at shooting ranges are rare, occurring at a rate of roughly 0.12 per million people.26

- Researchers at the University of Southern Mississippi and the New Jersey Gun Violence Research Center sought to determine if the type and number of firearms owned was associated with firearm suicide death, finding that handgun, but not shotgun, ownership was significantly associated with firearm suicide death.27

- Researchers at the University of Washington Firearm Injury and Policy Research Program studied youth firearm suicide attempt survivors, finding that these survivors had fewer prior suicide behaviors, fewer prior suicide attempts, and fewer preparatory acts compared to patients who attempted non-gun suicide.28

Studies on unintentional shootings included the following articles:

- James Price and colleagues examined unintentional firearm deaths among African American youth and determined that from 2010 to 2019, the mortality rate increased by 48% for African American children, while the rate for white children declined by 29%.29

- Researchers at the Oregon Health and Science University and the University of Texas studied unintentional firearm deaths in children ages 1–4 from 1999 to 2018, finding that these deaths increased exponentially over this period, particularly among non-Hispanic Black children.30

Studies on police shootings included the following:

- Michael Siegel and colleagues researched the factors associated with police shootings, with results suggesting that higher levels of concentrated disadvantage and higher levels of interpersonal gun violence are significant predictors of the likelihood of a fatal police shooting happening in a neighborhood.31

- Researchers at the New Jersey Gun Violence Research Center analyzed use of force incidents in New Jersey, finding that among incidents where a gun is brandished by police, Black and Hispanic residents are more likely to be shot and shot numerous times compared to white residents.32

- A group of researchers from the Global Burden of Disease, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study examined police violence and shootings in the US, determining that the age-adjusted mortality rate due to police violence rose 38% from the 1980s to the 2010s.33

Outcomes Studied

The public health approach to violence prevention is described by the CDC as consisting of four steps, each of which are rooted in the scientific method.34 These steps include defining the problem, identifying risk and protective factors, developing and testing prevention strategies, and assuring widespread adoption of effective injury prevention principles and strategies.2 Our review of articles published in 2021 found that the majority of research was focused on the first two steps, which are concerned with identifying and describing the problem of gun violence, versus the latter two steps, which are more concerned with solutions to the problem.

Problem-Focused Studies

The majority (70%) of studies in our review were focused on describing the problem of gun violence and the factors that impacted the likelihood of gun violence occurring. Among these studies, the plurality (30%) evaluated the nature, dynamics, or trends of gun violence or a specific type of gun violence. For example, the following new studies were published:

- Researchers at the University of California, San Francisco examined suicide decedents who died on their first attempt, finding that these individuals are more likely to use lethal means and are demographically different than people with a history of suicide attempts.35

- Lauren Magee explored how gun violence mortality differs by neighborhood, finding that gunshot wound mortality differs alongside neighborhood characteristics.36

- Joshua Freilich and colleagues analyzed open-source data to describe the patterns of gun violence incidents on school grounds.37

A similar number (26%) of problem-focused studies evaluated risk factors for offending and risk factors for gun violence victimization. Many of these studies examined the particular risk that guns create for firearm violence, as well as risks related to race and gender. New findings about the risk factors for gun violence included the following:

- Researchers at the University of California Firearm Violence Research Center identified associations between firearm purchasing characteristics and firearm suicide, finding that purchasers who were older at the time of their first purchase and those who purchased a revolver had greater risk of firearm suicide.38

- Researchers at the University of Michigan, Ohio State University, and the New Jersey Gun Violence Research Center found that early exposure to gun violence is significantly correlated with weapon carrying, weapon use or threats-to-use, arrests for weapons use, and criminally violent acts within the 10-year follow up period.39

- Researchers at the University of North Carolina examined civil protective order case data, adding additional evidence supporting the finding that gun access is strongly associated with higher levels of reported intimate partner violence.40

A number of problem-focused studies (19%) described non-injury or post-injury consequences of gun violence, such as the cost of gun violence and the mental health impacts of gun violence. Some examples of these studies included:

- Researchers at the University of South Carolina and the University of Washington Firearm Injury and Policy Research Program qualitatively studied survivors of firearm assaults and unintentional gun injuries, finding that many experienced psychological symptoms like post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and anxiety after their victimization.41

- Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania and Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia examined the negative mental health consequences for children exposed to neighborhood gun violence, finding that children who lived closest to the site of a shooting had higher odds of presenting to the emergency department with a mental health-related complaint.42

- Researchers at Stanford University reviewed a comprehensive national database to estimate the costs associated with pediatric firearm injuries, finding that costs for initial hospitalizations related to these injuries totaled approximately $109 million annually.43

Importantly, a relatively small number (7%) of studies examined any of these factors with respect to nonfatal shootings only. Limited availability and quality issues with nonfatal shooting data at both the national and state level have been well-documented,44 and appear to have impeded efforts to more specifically study this aspect of the gun violence epidemic. However, some important scholarship in this area found the following:

- Kathryn Schnippel and colleagues calculated nonfatal firearm injury estimates from a nationwide database, finding that for every person killed by a gun in the US, two more are wounded.45

- Researchers at the University of Washington Firearm Injury and Policy Research Program explored the role of firearms in nonfatal domestic violence, finding that nearly one in 10 US adults have experienced nonfatal firearm abuse by an intimate partner.46

- Researchers at the New Jersey Gun Violence Research Center examined the link between nonfatal gun violence and health behaviors in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, identifying a positive association between nonfatal shootings in neighborhoods and higher levels of physical inactivity and obesity among residents.47

Of particular interest in 2021, we identified 29 studies (8% of total sample) which examined the intersection of gun violence and the COVID-19 pandemic. These articles largely focused on homicides and COVID-19, as well as gun purchases during the pandemic. Among these studies were:

- An analysis from the University of California Firearm Violence Research Center which suggests that among 16 major US cities, increased physical distancing during the pandemic was associated with decreases in reported incidents of aggravated assault, interpersonal firearm violence, theft, rape, and robbery.48

- A survey from researchers at the Harvard Injury Control Center quantifying the rise in pandemic-era gun purchases and estimating that in 2020, 9.3 million people were newly exposed to firearms in the home.49

- A study from Renee Johnson and colleagues that investigated the association between gun ownership and perceptions about COVID-19 among Texas adults, finding that gun owners may be more likely than non-gun owners to believe that the threat of the pandemic was exaggerated.50

Solution-Focused Studies

Very few studies examined specific policies (18%) or programs (16%) that are intended to prevent gun violence. Of studies that did look at specific policies or programs, only a small fraction evaluated their impact on gun injuries or deaths. In fact, only three percent of reviewed studies were classified as policy evaluations that measured the impact of gun policy on violence.

Policy evaluation studies primarily measured whether policies reduced gun deaths; only one policy evaluation by Miriam Neufeld and colleagues quantified the impact of policy solutions on nonfatal gun violence.51 This study found that laws which prohibit people convicted of violent misdemeanors from having firearms and remove firearms from domestic violence offenders were associated with reductions in firearm injury-related hospitalization rates (20% and 17%, respectively).52

The plurality (38%) of policy evaluation studies examined the impact of combined gun policies, such as the overall number of gun policies or a gun law strength score, on gun violence. Importantly, all but one of these policy evaluations suggest that stronger gun laws were protective against death or injury for at least some of the studied populations.53 Of studies that evaluated the impact of a specific policy or policies, the most common types were evaluations of domestic violence-related firearm restrictions (25% of policy evaluations) and evaluations of safe storage and child access prevention law policies (25% of policy evaluations). Policy evaluation studies included the following articles:

- Researchers at the New Jersey Gun Violence Research Center found that states with greater numbers of gun safety laws had lower firearm homicide and firearm suicide rates compared to those with fewer gun safety laws.54

- Alexa Yakubovich and colleagues reviewed 25 studies that examined the impact of Stand Your Ground laws and concluded that in addition to having disparate racial impacts, these laws do not deter violent crime, and in many cases are associated with more violence.55

- Researchers at Michigan State University and the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health found that the inclusion of state-level relinquishment provisions for those subject to a domestic violence protection order were associated with a 16% reduction in firearm intimate partner homicide for white victims, but these same benefits were not observed for Black victims.56

- Researchers at the University of Wisconsin and Wisconsin Medical College found that the repeal of Wisconsin’s 48-hour waiting period on handgun purchases in 2015 was associated with an increase in firearm suicides among people of color and those living in urban counties in the state.57

Non-evaluation policy studies made up 82% of policy-related studies. These non-evaluation policy-related studies investigated other aspects of policy, including attitudes about gun policy—such as a study by researchers at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health finding that public opinion on gun safety policies differs by race and gun ownership status58—and the implementation of policy—such as a study by researchers at the University of Colorado and Denver Health Medical Center examining the use of Colorado’s extreme risk law in the first year after enactment.59

Importantly, none of the studies in our sample examined the criminal legal system impacts of policies, such as whether a particular policy had disparate impacts on criminal legal system outcomes, or the impacts of policies on gun ownership, such as whether a policy created new challenges in obtaining firearms for those legally permitted to do so.

As with policy evaluations, there were similarly only a small number of articles that studied particular programmatic strategies to prevent gun violence. Among the program-related studies in our 2021 sample, the majority (59%) explored firearm safety education programs or safe storage counseling programs. Among the research on these programs were the following articles:

- A study by researchers at the University of Washington and Seattle Children’s Hospital which found that distribution and training in the use of firearm storage devices to households with children with mental health complaints increased safe firearm storage behavior.60

- A study by Joan Asarnow and colleagues which qualitatively and quantitatively evaluated a web-based tool that could be used to support lethal means counseling for parents of suicidal teens.61

- A study by researchers at the University of Colorado and the Colorado School of Public Health which identified important steps for successfully implementing “gun shop projects,” which involve partnerships between firearm retailers and public health officials to promote gun safety.62

Conversely, less than one in five (17%) program-related studies evaluated community violence intervention (CVI) strategies. CVI programs are specifically designed to reduce gun violence in the most impacted communities by focusing resources on the small fraction of the population at highest risk for engaging in deadly violence. There are multiple CVI program models, including group violence intervention and relationship-based street outreach programs.

Among the CVI program studies, articles focused roughly equally on studies of street outreach programs (54%) and group violence intervention programs (46%). Important new findings about community violence intervention programs included:

- An evaluation of a focused deterrence intervention by researchers at Southern Illinois University, which found that the program was associated with a decrease in the number of shots fired in target areas, as well as increased feelings of safety among community members.63

- A case study of a hospital-based violence intervention program (HVIP) conducted by Sheetal Ranjan and colleagues, which emphasized the need to create and sustain internal support, community partnerships, and practitioner engagement for successful HVIP implementation.64

Groups of People Studied

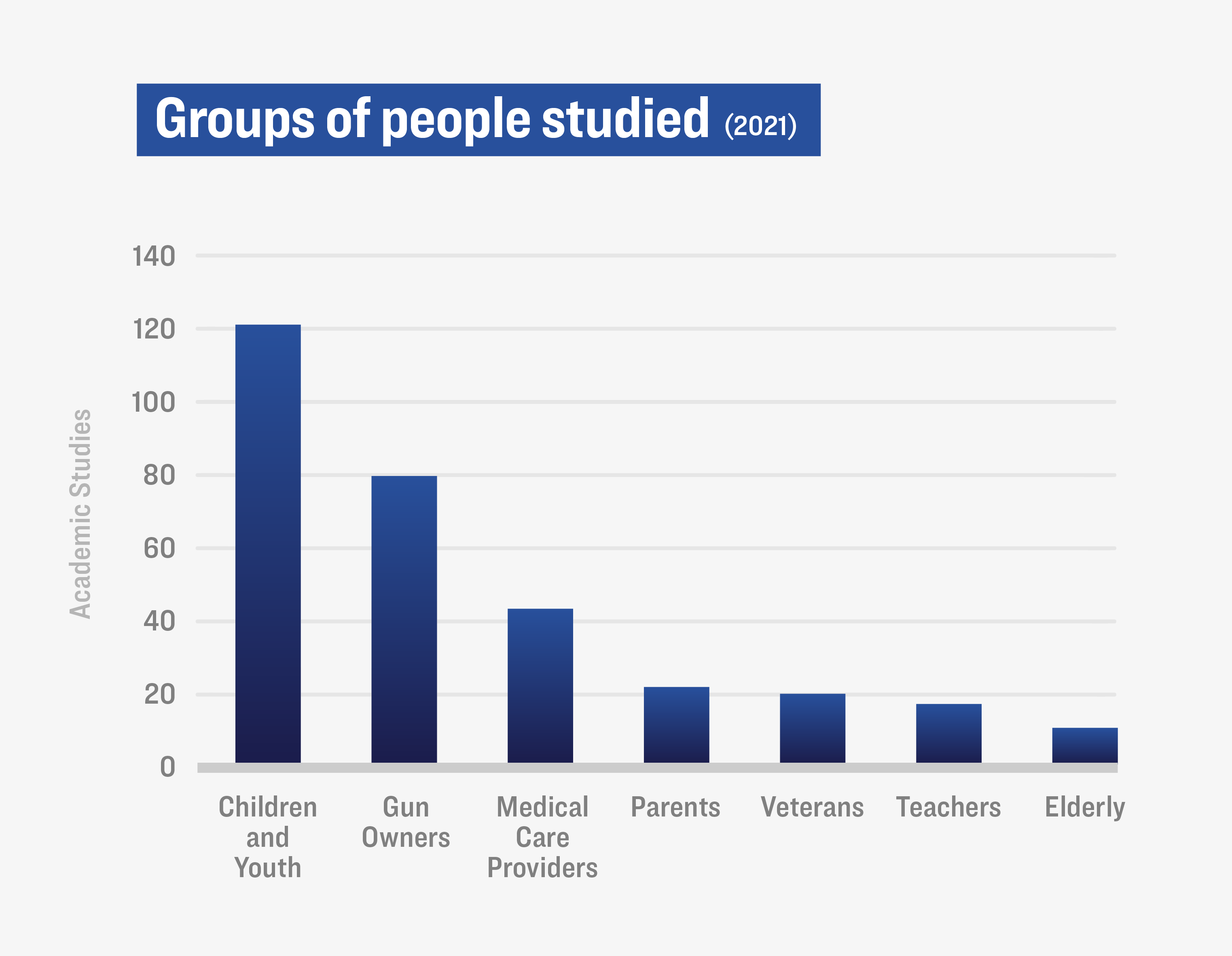

Gun violence touches every community across America, with some research suggesting that nearly all Americans will personally know a victim of gun violence in their lifetime.65 However, there are a number of people who may experience gun violence differently or uniquely because of their demographic or lifestyle characteristics—such as children, the elderly, and gun owners—as well as many groups of people who can play a particularly important role in gun violence prevention, such as medical care providers. We found that gun violence research in 2021 involved study of many of these groups of interest, but there were key differences in the frequency at which these groups were represented.

A quarter (25%) of studies tracked in 2021 focused on gun violence among children and youth. There were 10 times as many articles published on children and youth as older adults and the elderly. Some studies that focused on gun violence by age group included the following:

- A study by researchers at Northeastern University and the Harvard Injury Control Center, which replicated and expanded earlier findings66 that many children contradict the reports of their parents who often mistakenly believe that their children could not access a household firearm.67

- A survey of urban adolescents and young adults conducted by Rebeccah Sokol and colleagues, which found that higher levels of community violence were associated with higher levels of youth gun carrying, with an increase of this association among youth with stronger perceptions of police bias.68

- A qualitative study by researchers at the University of Colorado examining how caregivers identify and respond to concerns about firearm access among people with dementia.69

Gun owners were also given specific study in many 2021 research articles: 16% of articles provided new data or specific analysis of gun owners. A smaller number (4%) of articles examined veterans, who are often considered an important subset of gun owners, particularly given their heightened risk for firearm suicide.70 Gun owner-focused articles primarily included new findings on gun owner storage and firearm acquisition, while articles focused on veterans tended to examine firearm suicides among this group. For example:

- Claire Boine and colleagues used a modeling method to identify six unique sub-groups of gun owners, demonstrating the depths of diversity in the motivations for ownership and cultural salience of guns among gun owners.71

- Researchers at the University of California Firearm Violence Research Center surveyed Californians to discern patterns and practices of gun owners in California, with results suggesting that nearly two-thirds (65%) of Californians who owned firearms and lived in homes with minors did not store all their guns in the most secure manner.72

- Researchers at the Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Violence Prevention and Policy conducted a systematic review of the literature on veteran suicide, finding concordance that veterans face unique risk of firearm suicide and often exhibit risky firearm usage and storage behaviors.73

- Researchers from the Department of Veterans Affairs conducted focus groups with veterans to identify best practices for physicians to engage in firearm safety discussions related to suicide prevention.74

A number (9%) of articles focused on medical care providers, including doctors and nurses. Many of the studies that included a focus on medical professionals studied programmatic interventions that could be implemented in the clinical setting, and several of these articles examined how to get more clinicians involved in actions to prevent gun violence. New research findings related to clinicians and gun safety included:

- A study from researchers at Texas Children’s Hospital examining firearm safety counseling among pediatric healthcare providers found that while 86% of such providers agree that they should discuss firearms safety with parents, only 32% report routinely giving firearm safety counseling.75

- A study led by researchers on the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma in which more than 50,000 surgeons were surveyed and found to have firearms in the home and store such firearms unlocked and loaded at moderate frequencies (40% and 32%, respectively).76

Methods of Studies

The majority (77%) of published 2021 studies were purely quantitative; a smaller portion (15%) were purely qualitative. Few studies (5%) utilized a mixed methods approach. Qualitative research included important interviews with gun violence survivors and other stakeholders, such as a study from Jaclyn Schildkraut and colleagues describing the importance of survivor networks for people who have experienced a mass shooting.77

Very few studies (1.4%) involved participation from impacted communities, such as those living in communities with high rates of gun violence or survivors of gun violence, in the research design. While both gun owners and survivors were studied, neither of these groups were specifically engaged as research partners in any research project we reviewed, though it is possible that some researchers could fall into these groups themselves and not identify as such within the academic article. The few studies that did employ a community-researcher partnership or stakeholder-researcher partnership were all studies related to community violence intervention programs. Articles using this design included:

- A partnership between street outreach workers and academic researchers at DePaul University and the University of Illinois, which studied the use of a mobile application designed to support street outreach workers and found that the app supported outreach workers in building a counter-structure to traditional policing.78

- A collaboration between researchers at UC Berkeley and street outreach program staff, which described the core components of the street outreach program known as Advance Peace.79

- A study conducted by researchers at three Hartford, Connecticut, trauma centers and local law enforcement partners, which examined the impact of gunshot detection systems on crime and found that a number (43%) of gunshot events were not captured by the detection technology and that such systems did not improve response times in medical care for victims.80

Research Field

While the primary focus of this research tracking and review was to identify the topics covered in gun violence-related research, our collection of these articles also revealed important findings about the state of the gun violence prevention research field. For example, this collection found that less than one-third (32%) of studies tracked were available on open-access, meaning that they are free of cost and other barriers.

Additionally, this review helps illuminate the critical role that state-funded firearm violence research centers play in promulgating new research. Researchers at the three established state-funded research centers in operation in 2021 produced 15% of all the research studies included in the analytic sample. Importantly, these three research centers—in California, New Jersey, and Washington—appear to play an important role in providing specific and actionable information about violence and policy in the state, as evidenced by studies about gun violence or gun policy specifically in their state.

In fact, more studies examined gun violence and gun violence prevention in California than any other state, and the majority of California-specific studies were produced by the California Firearm Violence Research Center. These included:

- An analysis of California firearm purchasers which found that more than one in six handgun purchasers had a criminal charge history at the time of gun purchase.81

- A study of California firearm purchasers which found that people with a history of intimate partner violence at the time of gun purchase had an increased risk of subsequent arrest for a violent crime after purchase, compared to purchasers with no such criminal history.82

- Another study of California firearm purchasers which suggests that men with prior alcohol and drug charges at the time of handgun purchase had an increased risk of subsequent suicide after purchase compared with purchasers with a history of neither of alcohol nor drug charges.83

- A survey of how and where California gun purchasers obtain their firearms, which found that 17% of purchasers obtain their firearms without a background check, a far lower percentage than among states without universal background check laws.84

- A description of armed and prohibited persons in California—people who legally purchased firearms and then later became prohibited from ownership—finding that almost half of the nearly 19,000 armed and prohibited people in California were prohibited due to a felony conviction.85

- A qualitative evaluation of the implementation of California’s extreme risk law, known as the gun violence restraining order, which suggests that a lack of funding to support proactive implementation efforts hampered implementation and led to inconsistent use of the law across the state.86

As the field of gun violence research changes and new money is allocated for this vital work, this review can serve as a resource to help researchers, funders, and policymakers better work towards creating a more equitable, actionable research field and producing responsive research. The following recommendations outline the most urgent steps that should be taken to strengthen the research field, as evidenced by our review.

Fund More Research on Gun Violence

For this review, we collected nearly 500 articles that provided new data on gun violence or gun violence prevention. Previous studies would suggest that this number is higher than what we would have collected even just a few years ago.87 Increased funding for this critical research has been made available in recent years, and academic journals have actively encouraged more scholarship on this issue, which almost certainly augmented the number of articles collected this year.

Despite promising growth in the field, however, the number of publications on the causes, consequences, and solutions to gun violence are still only a fraction of what is expected compared to publications on other leading causes of death.4 The fact that these deficits have occurred for more than 25 years has only intensified these research gaps. Additionally, as we found in our review, there are areas of gun violence research that received little scholarship in 2021, which may have been due, in part, to the lack of funding available to conduct more rigorous, large-scale evaluations and data analyses.

Clearly, more funding is needed to adequately study this issue and its solutions. As a next step, we encourage Congress to include $50 million for gun violence research in the Consolidated Appropriations Act of Fiscal Year 2022—the same amount included in both House and Senate FY2022 appropriations bills and the amount requested by President Biden. Furthermore, we recommend that additional state, local, and private funders dedicate new monies to promulgate new gun violence research. Private funders should consider both creating their own process for funding proposals or contributing to existing firearm violence research grant programs.88

Our review also found that state-funded gun violence research centers play a key role in promoting scientific inquiry on gun violence and serve as an important funding stream for these research endeavors. Nearly one in seven of the studies we analyzed involved authorship by faculty in at least one of these centers, and research produced by these centers often provided state-specific information relevant to policymaking or implementation efforts. Given that only a small handful of states have established this important funding stream, we recommend that more states establish state-funded gun violence research centers with the goal of generating additional scholarship on gun violence and gun violence prevention.

Improve Data Collection on Gun Violence

In addition to providing funding for gun violence research, our review highlights the importance of designating funding to improve data collection systems on gun injuries and deaths. For example, despite the fact that multiple studies published this year found that gun injuries far outpace gun deaths in the United States, only a small fraction of studies specifically analyzed nonfatal shooting injuries, and only one study evaluated the impact of policy on nonfatal gun injuries. This lack of scholarship on nonfatal injuries, despite their outsized role in the gun violence epidemic, is likely due to the fact that there is not sufficient, accessible, quality data on nonfatal shootings for most states and localities.89 Additionally, national data on nonfatal gun injuries is based on estimates, and researchers have expressed concerns about the quality of demographic and intent-level breakdowns of this data.90

With more funding, programs designed to improve systems for data collection could be improved and expanded. In fact, in 2020, the CDC awarded funding to 10 state health departments as part of an initiative, known as Firearm Injury Surveillance Through Emergency Rooms (FASTER), to capture near-real-time data on emergency visits for nonfatal firearm injuries.91 Additional federal funding for gun violence research at the CDC could help expand this program—as well as other data collection programs—to more states to improve its utility for cross-state comparisons and national analyses.

Firearm morbidity and mortality data can also be improved through data-sharing agreements, often between public health and criminal justice agencies who collect data on unique aspects of this epidemic. It is critical that the federal government actively encourage, facilitate, and provide guidance for data linkage research across its organizations, including, for example, the CDC, the Bureau of Justice Statistics, and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives. Data-linking partnerships between these organizations would help provide a deeper, richer understanding of the victim, perpetrator, and weapons-related characteristics of incidents of gun violence, which could in turn influence prevention strategies.

Prioritize Gun Violence Prevention Policy and Program Evaluations

Among published research articles in 2021, studies describing the problem of gun violence outnumbered studies describing solutions to gun violence by a ratio of two to one. Studies that describe the epidemiology and risk factors of gun violence are important, as we cannot implement solutions without first understanding the problem to be addressed. However, our review shows the need for more research that helps to identify solutions to, rather than simply describe, the problem of gun violence. Specifically, we urge funders and researchers to prioritize policy and program evaluations in the coming years, with a focus on shoring up our understanding of how certain policy and programmatic solutions impact gun deaths and injuries.

Based on the gaps in policy-related studies, we would further recommend that a priority for future research should be studies that evaluate or include consideration of the unintended consequences of policy, related both to outcomes in the criminal legal system and impacts on legal gun ownership. Additionally, scholars should pursue additional study on the impacts of policy along the lines of different demographic characteristics and social determinants, as we saw in a few 2021 policy studies, so that we can better understand how impacts are distributed within communities.

Finally, while we saw important scholarship on programmatic responses to gun violence, studies in this area were largely skewed towards gun suicide prevention and child gun injury prevention, and many of the programs studied were implemented in clinical settings rather than other community spaces. Although both of these areas are critical, our findings suggest a need for additional study of programs that are more embedded within communities. In fact, given the historic rises in gun homicides over the last few years and the unprecedented proposals for investment in programs to address these increases, the field should prioritize further scholarship on community-based violence intervention programs in the coming years.

Publish More Responsive Research

Our review identified a number of studies examining the impact of COVID-19 on gun violence, gun purchasing, and gun attitudes. These studies provided crucial information about the drastic increases in gun violence that roughly coincided with the beginning of the pandemic. As policymakers and stakeholders continue to develop solutions to address the new patterns of gun violence and gun ownership, these studies will provide a crucial evidence base.

However, despite spikes in hate-motivated violence over the last few years, as well as renewed national focus on police violence and police shootings, our review suggests these topics received little scholarly attention in 2021. It is likely that to some extent, the lack of articles on these issues is due to the overall lack of funding for gun violence research, a lack of quality data on both police shootings33 and hate crimes,92 and expected lags due to the time it takes to conduct, peer-review, and publish new research. However, it is critical that the field of research publish studies that are responsive to urgent issues and urgent policy discussions of the times, and we encourage funders and researchers to prioritize these topics for future study.

Create More Community-Research Partnerships

As the field of gun violence research grows and new investigators pursue scholarship in this area, it is important that this field is open to and inclusive of community members, including those with lived experience of gun violence, gun owners, gun violence prevention practitioners, and other community stakeholders. Such work, often referred to as community-based participatory research or participatory action research, can help to elevate the perspectives of people with lived experience, disrupt the imbalanced power dynamic between researcher and research subject, and encourage community participation in action for change.93

However, our review found that community members and those with lived experience served as research partners in only a small handful of studies published over the past year. We encourage researchers and funders to prioritize research that equitably partners with community members and includes community perspectives to ensure that future research reflects and incorporates the experiences of those closest to this issue.

Make the Field of Research More Accessible

An essential component of an evidence-based approach to preventing gun violence is the dissemination of scientific research to those responsible for crafting, designing, and implementing responses. Therefore, it is vital that the field of gun violence prevention research is accessible to people outside of academia, including advocates, community stakeholders, practitioners, and policymakers. Unfortunately, our review found that less than a third of articles published in 2021 were available on open access, meaning that access to free academic articles was severely limited for those outside the research community.

In order to make the field of research more accessible, funders should, when possible, provide specific monies to make the articles they fund be available on open access. Additionally, academic journals should prioritize making articles about this urgent public health issue more easily available. For example, in 2018, as an incentive to encourage more action and collaboration on gun safety, the American Public Health Association announced that all research papers on public health and firearms published in the Association’s journal, the American Journal of Public Health, would be available to all free of charge.94 More academic journals and editors should prioritize this kind of open access.

When people think about what needs to be done to prevent gun violence, many things come to mind. There are calls for our leaders to have courage and pass the gun safety reforms we desperately need, for frontline workers to be better supported in their work, for gun owners to behave more responsibly and store their guns safely. All of these steps are critical. But it’s important to remember that research underlies each of these recommendations, and conducting more and better research is an essential step to helping to keep our communities safe from gun violence.

The recent investments in gun violence research will be lifesaving. We saw this in our review, where we analyzed numerous new studies with findings that will inform how we understand this crisis and what we must do to prevent it. These findings and findings from future studies will guide our efforts to prevent gun violence for years to come.

Gun deaths have reached some of their highest levels ever in the past few years. And even if it isn’t the first step many of us think of, research will help us solve this problem. The research field needs to be as strong and responsive as it can be to our current crisis. Despite all that we know, there are too many aspects of this epidemic we have not yet studied. We hope this review will help researchers, funders, policymakers, and stakeholders in their efforts to produce the kind of actionable, equitable research needed to help take action and save lives.

Special thanks to Emily Larsen for her assistance with this project.

JOIN THE FIGHT

Gun violence costs our nation 40,000 lives each year. We can’t sit back as politicians fail to act tragedy after tragedy. Giffords Law Center brings the fight to save lives to communities, statehouses, and courts across the country—will you stand with us?

Notes

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (WONDER), “Underlying Cause of Death, 1999–2020,” last accessed January 3, 2022, https://wonder.cdc.gov/.

- Id.

- “Research Funding,” Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence, last accessed January 11, 2022, https://giffords.org/issues/research-funding/.

- David E. Stark and Nigam H. Shah, “Funding and Publication of Research on Gun Violence and Other Leading Causes of Death,” JAMA 317, no. 1 (2017): 84–86.

- “Funded Research,” Violence Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, last accessed January 11, 2022, https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/firearms/funded-research.html; “NIH Awards Grants for Firearm Injury and Mortality Prevention Research,” National Institutes of Health, September 30, 2020, https://obssr.od.nih.gov/news-and-events/news/nih-awards-grants-firearm-injury-and-mortality-prevention-research; “NIH Awards 10 Grants Addressing Firearm Violence Prevention,” National Institutes of Health, September 21, 2021, https://obssr.od.nih.gov/news-and-events/news/director-voice/nih-awards-10-grants-addressing-firearm-violence-prevention; see also, Nidhi Subbaraman, “Gun Violence is Surging—Researchers Finally Have the Money to Ask Why,” Nature, July 21, 2021, https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-01966-0?proof=thttps%3A%2F%2Fwww.nature.com%2Farticles%2Fsj.bdj.2014.353%3Fproof%3Dt.

- “About the University of California Firearm Violence Research Center (UCFC),” UC Davis Health, last accessed January 11, 2022, https://health.ucdavis.edu/vprp/UCFC/index.html.

- Rutgers New Jersey Gun Violence Research Center, last accessed January 11, 2022, https://gunviolenceresearchcenter.rutgers.edu/about-us/.

- “Firearm Injury & Policy Research Program,” Harborview Injury Prevention and Research Program, University of Washington, last accessed January 11, 2022, https://hiprc.org/firearm/.

- “About the Collaborative,” National Collaborative on Gun Violence Research, last accessed January 11, 2022, https://www.ncgvr.org/about.html.

- “Our Grants,” National Collaborative on Gun Violence Research, last accessed October 27, 2021, https://www.ncgvr.org/grants.html.

- The Joyce Foundation has provided grant funding to Giffords Law Center, some of which has supported our own research work, among other projects.

- “25 Years of Impactful Grant Making: Gun Violence Prevention Research Supported by the Joyce Foundation,” The Joyce Foundation, August 2019, https://assets.joycefdn.org/content/uploads/Joyce_Report_v5.pdf?mtime=20210505151404&focal=none.

- “Cost Estimates of Federal Funding for Gun Violence Research and Data Infrastructure,” Health Management Associates, July 13, 2021, https://assets.joycefdn.org/content/uploads/CostEstimateofFederalFundingforGunViolenceResearch.pdf?mtime=20210712175851&focal=none.

- Jeff Tollefson, et al., “Biden Pursues Giant Boost for Science Spending,” Nature, April 9, 2021, https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-00897-0.

- “Expert Panel on Firearms Data Infrastructure,” NORC at the University of Chicago, last accessed January 11, 2022, https://www.norc.org/Research/Projects/Pages/expert-panel-on-firearms-data-infrastructure.aspx.

- John K. Roman, “A Blueprint for a U.S. Firearms Data Infrastructure,” NORC at the University of Chicago, October 2020, https://www.norc.org/PDFs/Firearm%20Data%20Infrastructure%20Expert%20Panel/A%20Blueprint%20for%20a%20U.S.%20Firearms%20Data%20Infrastructure_NORC%20Expert%20Panel%20Final%20Report_October%202020.pdf.

- Ted Alcorn, “The Next 100 Questions: A Research Agenda For Ending Gun Violence,” The Joyce Foundation, December 2020, https://assets.joycefdn.org/content/uploads/TJF-The-Next-100-Questions-A-Research-Agenda-for-Ending-Gun-Violence.pdf?mtime=20210504122403&focal=none.

- Medical case studies excluded from our study involved studies that solely described the physiology of gunshot wounds or the medical treatment or management of gunshot injuries. Additionally, medical case studies were only flagged in our original tracking if they reviewed the cases of two or more patients. Thirty-five such case study articles were tracked, but removed from our final analytic sample. Sixty articles that focused solely on non-US gun violence were removed from our final analytic sample. Of note, there was overlap in these categories, with several of the international studies discussing the medical treatment and management of gunshot wound injuries.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (WONDER), “Underlying Cause of Death, 1999–2020,” last accessed January 3, 2022, https://wonder.cdc.gov/.

- See, e.g., “Hate Crime Data Explorer,” Federal Bureau of Investigation, last accessed January 6, 2022, https://crime-data-explorer.fr.cloud.gov/pages/explorer/crime/hate-crime; Aggie Yellow Horse, Russell Jeung, and Ronae Matriano, “Stop AAPI Hate National Report,” Stop AAPI Hate, 2021, https://stopaapihate.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/21-SAH-NationalReport2-v2.pdf; “Hate Crimes up 100% in New York City This Year, Driven by Crimes Against the Asian Community, Police Say,” CBS News, December 8, 2021, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/hate-crimes-new-york-city-up-100-percent-anti-asian/.

- Scott R. Kegler, Linda L. Dahlberg, and Alana M. Vivolo-Kantor, “A Descriptive Exploration of the Geographic and Sociodemographic Concentration of Firearm Homicide in the United States, 2004–2018,” Preventive Medicine 153 (2021).

- Jason R. Silva, “Mass Shooting Outcomes: A Comparison of Completed, Attempted, Failed, and Foiled Incidents in America,” Deviant Behavior (2021): 1–20.

- Lisa B. Geller, Marisa Booty, and Cassandra K. Crifasi, “The Role of Domestic Violence in Fatal Mass Shootings in the United States, 2014–2019,” Injury Epidemiology 8, no. 1 (2021): 1–8.

- T.K. Logan and Kellie Lynch, “Exploring the Nature, Scope, and Impact of Firearm Threats Among Women with Cohabitating Versus Noncohabitating Partners: Considerations for the Boyfriend Loophole,” Violence and Gender (2021).

- Stephanie L. Bonne, et al., “Prevention of Firearm Violence Through Specific Types of Community-based Programming: an Eastern Association for The Surgery of Trauma Evidence-based Review,” Annals of Surgery 274, no. 2 (2021): 298–305.

- Catherine Barber, Hannah Walters, Thomas Brown, and David Hemenway, “Suicides at Shooting Ranges,” Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention 42, no. 1 (2021).

- Allison E. Bond and Michael D. Anestis, “Firearm Type and Number: Examining Differences Among Firearm Owning Suicide Decedents,” Archives of Suicide Research (2021): 1–8.

- Vivian H. Lyons, et al., “Life Experiences Preceding High Lethality Suicide Attempts in Adolescents at a Level I Regional Trauma Center,” Suicide and Life–Threatening Behavior 51, no.5 (2021): 836–843.

- James H. Price, Jagdish Khubchandani, and Erica Payton Foh, “Unintentional Firearm Mortality in African–American Youths, 2010–2019,” Journal of the National Medical Association (2021).

- Archie Bleyer, Stuart E. Siegel, and Charles R. Thomas Jr, “Increasing Rate of Unintentional Firearm Deaths in Youngest Americans: Firearm Prevalence and COVID-19 Pandemic Implication,” Journal of the National Medical Association 113, no. 3 (2021): 265–277.

- Michael Siegel, Michael Poulson, Rahul Sangar, and Jonathan Jay, “The Interaction of Race and Place: Predictors of Fatal Police Shootings of Black Victims at the Incident, Census Tract, City, and State Levels, 2013–2018,” Race and Social Problems (2021): 1–21.

- Richard Stansfield, Ethan Aaronson, and Adam Okulicz-Kozaryn, “Police Use of Firearms: Exploring Citizen, Officer, and Incident Characteristics in a Statewide Sample,” Journal of Criminal Justice 75 (2021).

- GBD 2019 Police Violence US Subnational Collaborators, “Fatal Police Violence by Race and State in the USA, 1980–2019: a Network Meta-regression,” The Lancet 398, no. 10307 (2021): 1239–1255.

- “The Public Health Approach to Violence Prevention,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Violence Prevention, January 18, 2022, https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/about/publichealthapproach.html.

- Joshua T. Jordan and Dale E. McNiel, “Characteristics of Persons Who Die on Their First Suicide Attempt: Results From the National Violent Death Reporting System,” Psychological Medicine 50, no. 8 (2020): 1390–1397.

- Lauren A. Magee, “Differences in Mortality Rates of Gunshot Victims: The Influence of Neighborhood Social Processes,” Homicide Studies (2021).

- Joshua D. Freilich, et al., “Using Open-source Data to Better Understand and Respond to American School Shootings: Introducing and Exploring the American School Shooting Study (TASSS),” Journal of School Violence (2021): 1–26.

- Julia P. Schleimer, Rose Kagawa, and Hannah S. Laqueur, “Handgun Purchasing Characteristics and Firearm Suicide Risk: a Nested Case–control Study,” Injury Epidemiology 8, no. 1 (2021): 1–10.

- L. Rowell Huesmann, et al., “Longitudinal Predictions of Young Adults’ Weapons Use and Criminal Behavior From Their Childhood Exposure to Violence,” Aggressive Behavior 47, no. 6 (2021): 621–634.

- Julie M. Kafka, Kathryn E. Moracco, Deanna S. Williams, and Claire G. Hoffman, “What is the Role of Firearms in Nonfatal Intimate Partner Violence? Findings From Civil Protective Order Case Data,” Social Science & Medicine 283 (2021).

- Ashley B. Hink, Dana L. Atkins, and Ali Rowhani-Rahbar, “Not All Survivors are the Same: Qualitative Assessment of Prior Violence, Risks, Recovery and Perceptions of Firearms and Violence Among Victims of Firearm Injury,” Journal of Interpersonal Violence (2021).

- Aditi Vasan, et al., “Association of Neighborhood Gun Violence With Mental Health–Related Pediatric Emergency Department Utilization,” JAMA Pediatrics 175, no. 12 (2021): 1244–1251.

- Jordan S. Taylor, et al., “Financial Burden of Pediatric Firearm-related Injury Admissions in the United States,” PLOS ONE 16, no. 6 (2021).

- See, Sean Campbell and Daniel Nass, “The CDC’s Gun Injury Data Is Becoming Even More Unreliable,” The Trace, March 11, 2019, https://www.thetrace.org/2019/03/cdc-nonfatal-gun-injuries-update/.

- Kathryn Schnippel, et al., “Nonfatal Firearm Injuries by Intent in the United States: 2016–2018 Hospital Discharge Records from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project,” Western Journal of Emergency Medicine 22, no. 3 (2021).

- Avanti Adhia, et al., “Nonfatal Use of Firearms in Intimate Partner Violence: Results of a National Survey,” Preventive Medicine 147 (2021).

- Daniel C. Semenza and Richard Stansfield, “Non-fatal Gun Violence and Community Health Behaviors: A Neighborhood Analysis in Philadelphia,” Journal of Behavioral Medicine (2021): 1–9.

- Julia P. Schleimer, et al., “Physical Distancing, Violence, and Crime in US Cities During the Coronavirus Pandemic,” Journal of Urban Health (2021): 1–5.

- Matthew Miller, Wilson Zhang, and Deborah Azrael, “Firearm Purchasing During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Results from the 2021 National Firearms Survey,” Annals of Internal Medicine (2021).

- Renee M. Johnson, et al., “Differences in Beliefs about COVID-19 by Gun Ownership: a Cross–sectional Survey of Texas Adults,” BMJ Open 11, no. 11 (2021).

- One study by Tiara Willie and colleagues examined the impact of state intimate partner violence (IPV) restrictions on injuries among IPV survivors, finding that state policies which prohibit firearm possession and specifically require firearm relinquishment were associated with lower odds of injury among IPV survivors. However, injuries in this study were not firearm specific, asking victims about all types of nonfatal victimization. See Tiara C. Willie, et al., “Associations Between State Intimate Partner Violence-related Firearm Policies and Injuries Among Women and Men Who Experience Intimate Partner Violence,” Injury Epidemiology 8, no. 1 (2021): 1–10.

- Miriam Y. Neufeld, Michael Poulson, Sabrina E. Sanchez, and Michael B. Siegel, “State Firearm Laws and Nonfatal Firearm Injury-Related Inpatient Hospitalizations: A Nationwide Panel Study,” The Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery (2021).

- For this data point, we considered studies that found that the presence of a gun safety law was associated with a decrease in gun deaths or injuries for at least one group or population studied. We also considered studies that found that the removal of a gun safety law was associated with increases in gun violence, which would suggest the benefits (or protective nature of) stronger gun safety regulations. Studies that analyzed multiple policies needed to find a benefit associated with at least one restrictive gun policy to be counted.

- John F. Gunn, et al., “The Impact of Firearm Legislation on Firearm Deaths, 1991–2017,” Journal of Public Health (2021).

- Alexa R. Yakubovich, et al., “Effects of Laws Expanding Civilian Rights to Use Deadly Force in Self-defense on Violence and Crime: a Systematic Review,” American Journal of Public Health 111, no. 4 (2021): e1–e14.

- Mikaela A. Wallin, Charvonne N. Holliday, and April M. Zeoli, “The Association of Federal and State-level Firearm Restriction Policies with Intimate Partner Homicide: a Re-analysis by Race of the Victim,” Journal of Interpersonal Violence (2021).

- Zachary R. Dunton, et al., “The Association Between Repealing the 48-hour Mandatory Waiting Period on Handgun Purchases and Suicide Rates in Wisconsin,” Archives of Suicide Research (2021): 1–9.

- Cassandra K. Crifasi, et al, “Public Opinion on Gun Policy by Race and Gun Ownership Status,” Preventive Medicine 149 (2021).

- Leslie M. Barnard, et al., “Colorado’s First Year of Extreme Risk Protection Orders,” Injury Epidemiology 8, no. 1 (2021): 1–7.

- Neil G. Uspal, et al., “Impact of a Firearm Safety Device Distribution Intervention on Storage Practices After an Emergent Mental Health Visit,” Academic Pediatrics 21, no. 7 (2021): 1209–1217.

- Joan R. Asarnow, et al., “’Lock and Protect’: Development of a Digital Decision Aid to Support Lethal Means Counseling in Parents of Suicidal Youth,” Frontiers in Psychiatry 12 (2021).

- Evan Polzer, Sara Brandspigel, Timothy Kelly, and Marian Betz, “‘Gun Shop Projects’ for Suicide Prevention in the USA: Current State and Future Directions,” Injury Prevention 27, no. 2 (2021): 150–154.

- T.R. Kochel, Seyvan Nouri, and S. Yaser Samadi, “Impact of Focused Deterrence on Lived Experiences With Gangs and Gun Violence: Extending Effects Beyond Officially Recorded Crime,” Criminal Justice Policy Review (2021).

- Sheetal Ranjan, Aakash K. Shah, C. Clare Strange, and Kate Stillman, “Hospital-based Violence Intervention: Strategies for Cultivating Internal Support, Community Partnerships, and Strengthening Practitioner Engagement,” Journal of Aggression, Conflict and Peace Research (2021).

- Bindu Kalesan, Janice Weinberg, and Sandro Galea, “Gun Violence in Americans’ Social Network During Their Lifetime,” Preventive Medicine 93 (2016): 53–56. See also, K Parker, et al., “America’s Complex Relationship with Guns: An In-depth Look at the Attitudes and Experiences of U.S. Adults,” Pew Research Center’s Social & Democratic Trends Project, June 22, 2017, https://pewrsr.ch/2txQZSP.

- Frances Baxley and Matthew Miller, “Parental Misperceptions About Children and Firearms,” Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 160, no. 5 (2006): 542–547.

- Carmel Salhi, Deborah Azrael, and Matthew Miller, “Parent and Adolescent Reports of Adolescent Access to Household Firearms in the United States,” JAMA Network Open 4, no. 3 (2021): e210989–e210989.

- Rebeccah L. Sokol, et al., “The Association Between Perceived Community Violence, Police Bias, Race, and Firearm Carriage Among Urban Adolescents and Young Adults,” Preventive Medicine (2021).

- Evan R. Polzer, et al., “Firearm Access and Dementia: A Qualitative Study of Reported Behavioral Disturbances and Responses,” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society (2021).

- “2021 National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report,” US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention, September 2021, https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/data-sheets/2021/2021-National-Veteran-Suicide-Prevention-Annual-Report-FINAL-9-8-21.pdf.

- Claire Boine, Kevin Caffrey, and Michael Siegel, “Who Are Gun Owners in the United States? A Latent Class Analysis of the 2019 National Lawful Use of Guns Survey,” Sociological Perspectives (2021).

- Rocco Pallin, Garen J. Wintemute, and Nicole Kravitz-Wirtz, “Firearm Practices, Perceptions of Safety, and Opinions on Injury Prevention Strategies Among California Adults With vs Without Children,” JAMA Network Open 4, no. 8 (2021): e2119146–e2119146.

- Jason Theis, et al., “Firearm Suicide Among Veterans of the US Military: a Systematic Review,” Military Medicine 186, no. 5-6 (2021): e525–e536.

- Steven K. Dobscha, et al., “Strategies for Discussing Firearms Storage Safety in Primary Care: Veteran Perspectives,” Journal of General Internal Medicine 36, no. 6 (2021): 1492–1502.

- Avni M. Bhalakia, “Pediatric Providers’ Knowledge, Attitudes, Practice, and Barriers to Firearms Safety Counseling,” Southern Medical Journal 114, no. 10 (2021): 636–639.

- Brendan T. Campbell, et al., “Firearm Storage Practices of US Members of the American College of Surgeons,” Journal of the American College of Surgeons 233, no. 3 (2021): 331–336.

- Jaclyn Schildkraut, Evelyn S. Sokolowski, and John Nicoletti, “The Survivor Network: the Role of Shared Experiences in Mass Shootings Recovery,” Victims & Offenders 16, no. 1 (2021): 20–49.

- Jessa Dickinson, et al., “Amplifying Community-led Violence Prevention as a Counter to Structural Oppression,” Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction 5, no. CSCW1 (2021): 1–28.

- Jason Corburn, Devone Boggan, and Khaalid Muttaqi, “Urban Safety, Community Healing & Gun Violence Reduction: the Advance Peace Model,” Urban Transformations 3, no. 1 (2021): 1–12.

- Brendan R. Gontarz, et al., “Firearm Acoustic Detection in Hartford, Connecticut: Outcomes of a Trauma Center–Law Enforcement Collaboration,” Cureus 13, no. 10 (2021).

- Veronica A. Pear, et al., “Criminal Charge History, Handgun Purchasing, and Demographic Characteristics of Legal Handgun Purchasers in California,” Injury Epidemiology 8, no. 1 (2021): 1–9.

- Elizabeth A. Tomsich, et al., “Intimate Partner Violence and Subsequent Violent Offending Among Handgun Purchasers,” Journal of Interpersonal Violence (2021).

- Julia P. Schleimer, et al., “Alcohol and Drug Offenses and Suicide Risk Among Men Who Purchased a Handgun in California: A Cohort Study,” Preventive Medicine 153 (2021).

- Nicole Kravitz-Wirtz, et al., “Firearm Purchases Without Background Checks in California,” Preventive Medicine 145 (2021).

- Veronica A. Pear, et al., “Armed and Prohibited: Characteristics of Unlawful Owners of Legally Purchased Firearms,” Injury Prevention 27, no. 2 (2021): 145–149.

- Veronica A. Pear, et al., “Implementation and Perceived Effectiveness of Gun Violence Restraining Orders in California: A Qualitative Evaluation,” PLoS One 16, no. 10 (2021).

- Sixtine Gurrey, et al., “Firearm-related Research Articles in Health Sciences by Funding Status and Type: A Scoping Review,” Preventive Medicine Reports 24 (2021).

- For example, in 2020, the Missouri Foundation for Health provided funding to the National Collaborative on Gun Violence Research to fund Missouri-specific studies. “New Foundation Partnership Will Enable Valuable Missouri-Specific Gun Violence Research,” Missouri Foundation for Health, January 3, 2020, https://mffh.org/news/new-foundation-partnership-will-enable-valuable-missouri-specific-gun-violence-research/. The Missouri Foundation for Health has provided grant funding to Giffords Law Center; these funds have not been used to directly support our research team.

- Sean Campbell and Daniel Nass, “The CDC’s Gun Injury Data Is Becoming Even More Unreliable,” The Trace, March 11, 2019, https://www.thetrace.org/2019/03/cdc-nonfatal-gun-injuries-update/.

- Id; Catherine Barber, Eric Goralnick, and Matthew Miller, “The Problem With ICD-coded Firearm Injuries,” JAMA Internal Medicine (2021).

- May Chen, “CDC’s Firearm Surveillance Through Emergency Rooms (FASTER): Overview and Updates,” Board of Scientific Counselors, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, February 16, 2021, https://www.cdc.gov/injury/pdfs/bsc/chen_bsc-presentation-mc.pdf.

- See, e.g., Ken Schwencke, “Why America Fails at Gathering Hate Crime Statistics,” ProPublica, December 4, 2017, https://www.propublica.org/article/why-america-fails-at-gathering-hate-crime-statistics.

- Fran Baum, Colin MacDougall, and Danielle Smith, “Participatory Action Research,” Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 60, no. 10 (2006).

- “APHA Opens Public Access to Firearms Research Published in American Journal of Public Health,” American Public Health Association, March 6, 2018, https://www.apha.org/news-and-media/news-releases/apha-news-releases/2018/ajph-gun-violence-collection.