America at a Crossroads

Reimagining Federal Funding to End Community Violence

For decades, our nation has failed to adequately address the gun violence that plagues underserved communities in our cities.

Federal funding for violent crime prevention has been insufficient, unfocused, and sometimes harmful, contributing to the mass incarceration that has hollowed out communities of color while failing to significantly decrease homicides.

Preface

America at a Crossroads Executive Summary

As a country and as a gun violence prevention movement, we must reckon with the fact that for decades, we have overwhelmingly pursued the wrong strategies and tactics, locking up scores of young men of color while simultaneously failing to protect the most vulnerable members of our society from gun violence.

Yet in the midst of these missteps and missed opportunities, there’s still hope.

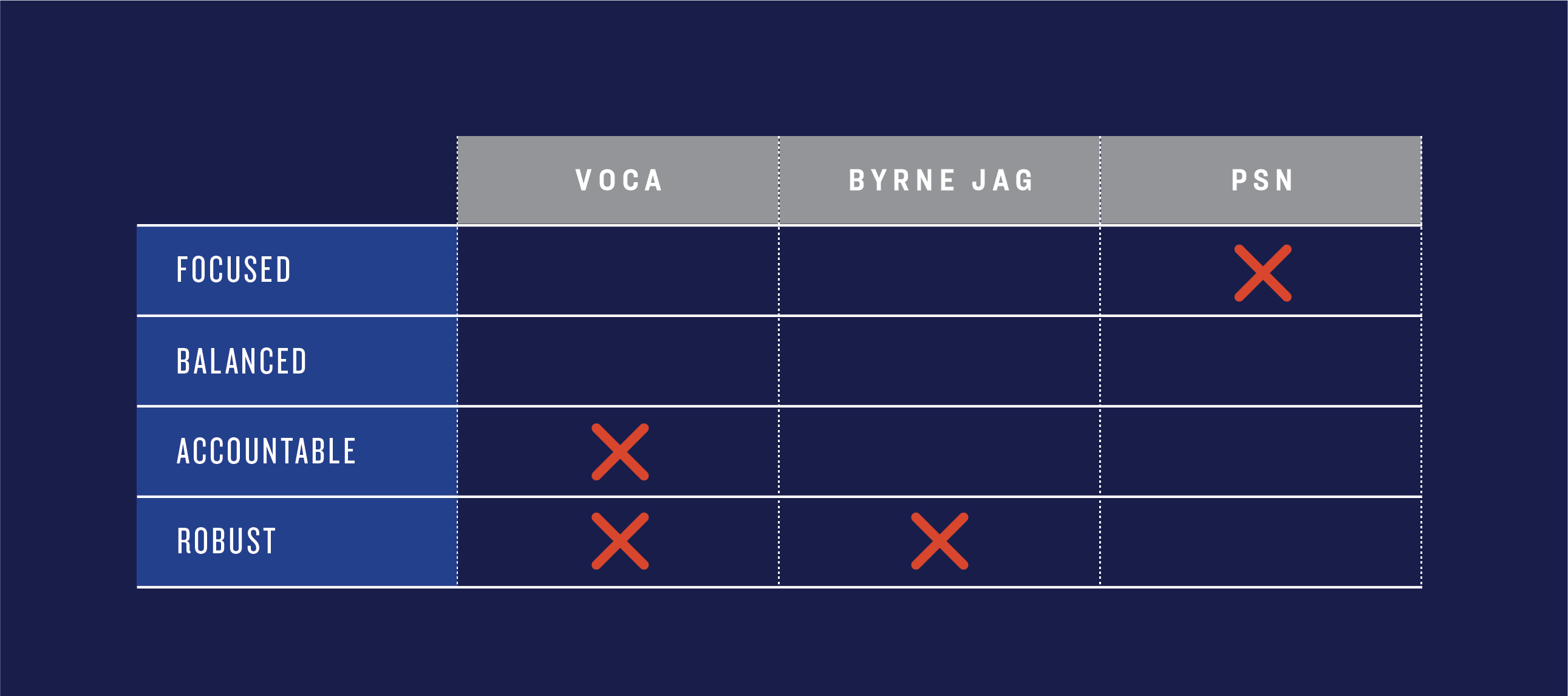

Each of the major federal funding streams explored here—the Victims of Crime Act, the Edward Byrne Memorial Justice Assistance Grant, and Project Safe Neighborhoods—can be used to fund evidence-informed, community-based violence prevention strategies that actually work. But it will take intentional and sustained advocacy to move these systems in a different direction.

In this report, we examine each program in detail and identify ways for advocates to help better leverage these existing opportunities. We also recommend structural reforms to improve each program. Finally, we propose an overhaul to the federal system, centered on the creation of an Office on Community Violence, modeled after the Office on Violence Against Women.

Our government has a mandate to protect its citizens, including and especially from a devastating epidemic perpetuated by corporate special interests like the gun lobby. We refuse to accept these deaths as inevitable, or to write off any American because of the color of their skin or their zip code. Our leaders can and must do better, and we will do everything in our power to hold them accountable until they do.

MEDIA REQUESTS

Our experts can speak to the full spectrum of gun violence prevention issues. Have a question? Email us at media@giffords.org.

Contact

Introduction

The world was dealing with a global pandemic that would go on to kill millions of people. The United States also faced a looming presidential election, protests and uprisings in cities across the country, and tremendous social and political tension around racial injustice, police brutality, and economic inequality.

The year? 1968.

As the US struggled to confront many of the same issues it still faces today, the Johnson administration appointed a commission to answer three fundamental questions about protests in major American cities: “What happened? Why did it happen? What can be done to prevent it from happening again?”1

At that time, the most recent government investigation into civil unrest and violence was the McCone Commission, which explored the roots of the Watts uprisings in 1965 and ultimately accused “riffraff” of spurring unrest, furthering the widely held belief that the protests were simply an outlet for the perceived “violent tendencies” of angry young men of color and groups with “radical” social agendas.2

After a seven-months-long investigation, which included public hearings in cities around the country, Johnson’s commission, led by Illinois Governor Otto Kerner Jr., released its findings. The Kerner Report was issued on February 29, 1968, and became an instant national bestseller.3

In sharp contrast to the McCone Commission, the Kerner Report concluded that one of the main causes of violence and civil unrest in cities was racism. The report found that white America bore much of the responsibility for uprisings in communities of color, declaring that “racism—not Black anger—turned the key that unlocked urban American turmoil.”4

The Kerner Report called for the creation of new jobs, construction of new housing, and an end to de facto segregation.5 It recommended that the government provide needed services, hire more diverse and culturally sensitive police forces, and invest billions in tackling segregation. In short, the Kerner Report called for a huge investment into communities of color and a concerted effort to bring fairness and legitimacy to police forces, many of the same solutions that are central to the Black Lives Matter movement.6

White backlash to the Kerner Report was immediate. Polls showed that 53 percent of white Americans condemned the claim that racism had caused the riots, while 58 percent of Black Americans agreed with the findings.7 The Kerner Report’s findings caught President Johnson off guard and he responded by simply ignoring them—even though they constituted the painstakingly detailed recommendations of a respected group of political leaders he himself had appointed. Instead, Johnson continued to embrace “a set of policies that managed problems of poverty and inequality through policing and surveillance of low-income communities and incarceration.”8

America’s response to the Kerner Report helped lay the foundation for the law-and-order campaign that helped get Richard Nixon elected to the presidency later that year. Nixon’s campaign rhetoric ultimately materialized as national policy in the form of the “war on drugs,” which formally launched in 1971.9 Years later, Nixon’s domestic policy chief, John Ehrlichman, admitted that the war on drugs was intentionally designed to destabilize communities of color, particularly Black communities.10

This racist “law and order” approach took the country down an incredibly destructive path. Decades later, the US has the world’s largest prison population—housing 25% of the world’s prisoners despite having only 5% of its population—and a criminal justice system that wreaks havoc on communities of color.11 Despite bipartisan calls for change, America is still tremendously segregated, and inequality is the worst it’s been since the 1920s.12

Racism—not Black anger—turned the key that unlocked American turmoil.

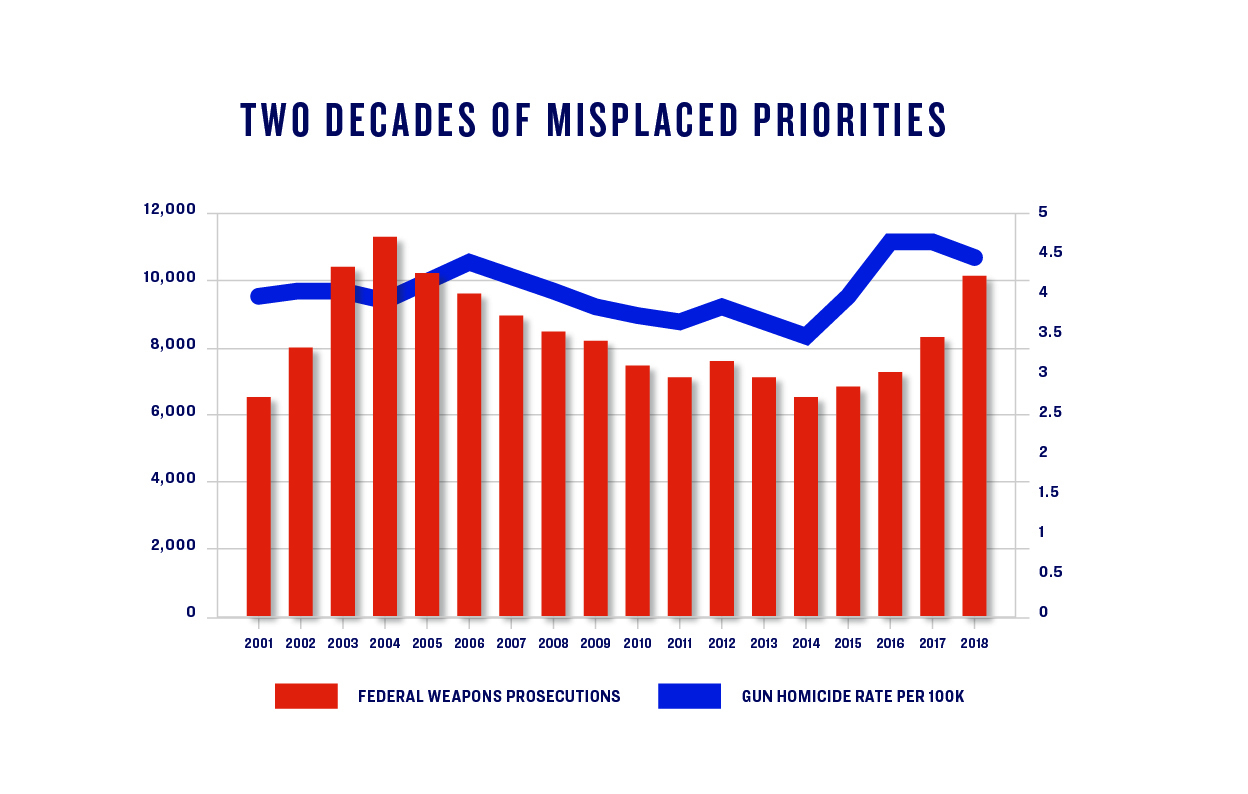

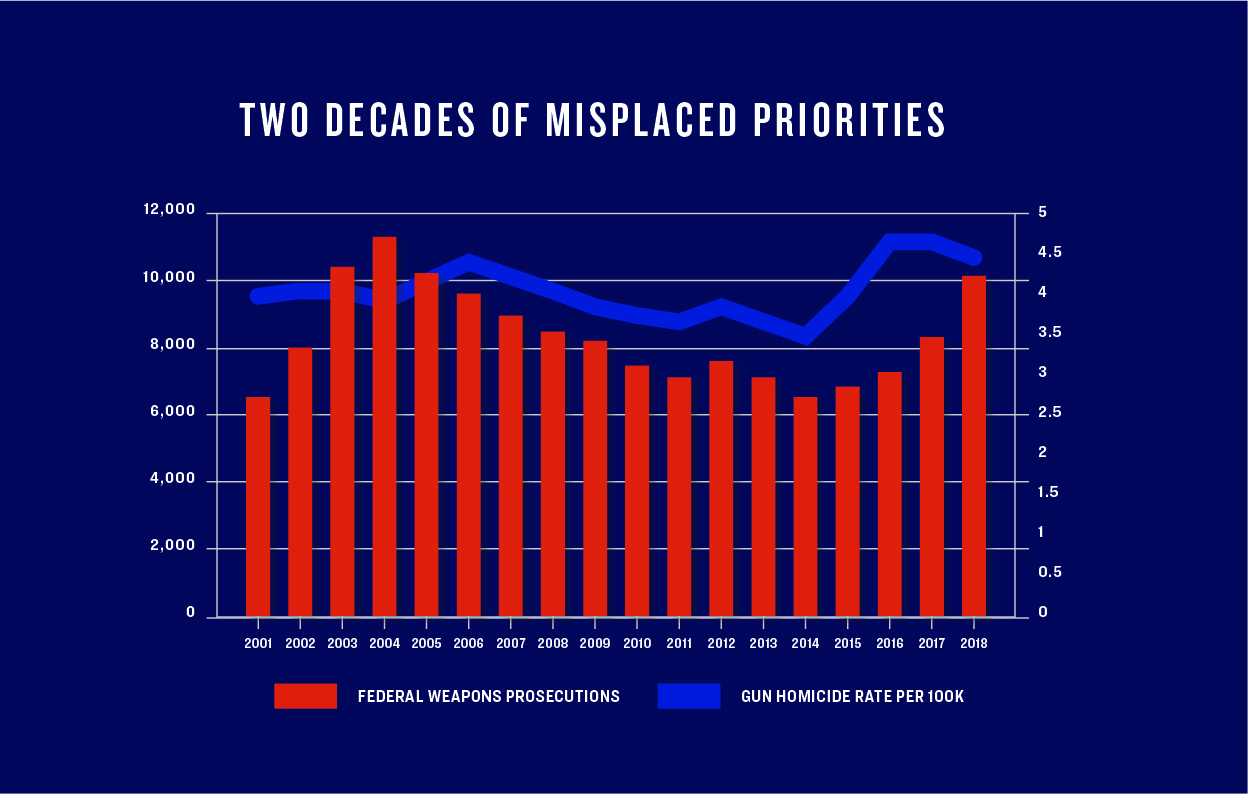

While violence has decreased since its peak in the 1990s, it has remained essentially flat over the last two decades. Summer 2020 saw an increase in violence in a number of cities across the country, attempts by our president to employ the National Guard against American citizens, and racist rhetoric from the highest office in the land—coupled with a call to return to “law and order.”13 With the election of Joe Biden and Kamala Harris, America finds itself at a crucial crossroads much like the one our country faced in 1968.

The choice is now ours to make: will we travel down a path of over-policing, systemic racism, and mass incarceration? Or will we instead make a meaningful commitment to reckoning, reconciliation, and reform?

One of the keys to achieving a more just and more peaceful America will be focusing significant investments on strategies that will reduce violence in our most impacted neighborhoods, while simultaneously decreasing law enforcement’s harmful footprint, particularly in communities of color.14 This is because violence is both a symptom and a root cause of inequality. Acts of violence spread through a community much like a virus: exposure to violence puts people at greater risk of future violence.15

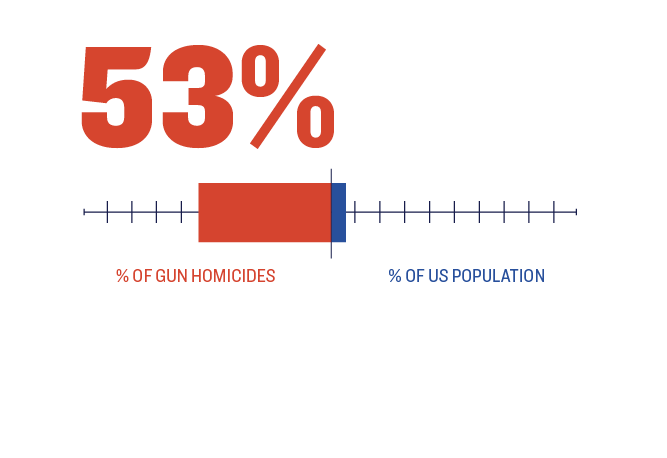

Over half of gun homicide victims are Black men

Source

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (WONDER), “Underlying Cause of Death, 2018-2022, Single Race,” last accessed May 28, 2024, https://wonder.cdc.gov/.

Violence, which occurs disproportionately in underserved communities of color, leads to high levels of PTSD and other negative health effects, including higher rates of heart disease and even cancer.16 Violence also reduces educational opportunities and attainment: studies have shown that young people who live in areas where gunfire is more common perform worse on tests, and in the immediate aftermath of shootings, test scores drop considerably.17 While we need to address many interlocking systems in order to achieve true safety and equality in the US, community violence is one of the fundamental issues to prioritize because of the hierarchy of needs. Improved schools, for example, cannot be effective if students must dodge bullets on their way to and from class.18

There are various forms of violence, and each requires a slightly different response. This report is focused on “community violence,” which we define generally as serious violence committed by one person against another outside of the context of a romantic relationship. Community violence includes homicides, nonfatal shootings, and stabbings, and both the perpetrators and victims of community violence are disproportionately young men of color.19

A number of violence intervention and prevention strategies exist to help heal our most underserved neighborhoods without contributing to mass incarceration—but we have yet to invest in these solutions in a manner that will bring them to scale. Giffords has previously published reports exploring how these strategies have been successful at the city and state levels. Although we know what works when it comes to reducing community violence, and that enormous benefits accrue to the entire country when violence levels are successfully lowered,20 our national policies still do not come close to reflecting the importance, gravity, and urgency of this issue.

America at a Crossroads takes a look at the current federal landscape when it comes to addressing community violence and provides readers with a snapshot of current investments, an analysis of opportunities to leverage existing funds more effectively, and a call to dramatically rethink our nation’s investments in strategies to reduce community violence.

This report and our organization’s community violence work is premised on four fundamental truths:

First, gun violence is an ongoing public health epidemic in the United States, claiming nearly 40,000 lives and causing tens of thousands of injuries each year. Every single one of these deaths and injuries is both tragic and preventable.21

Second, the majority of gun homicides come not from headline-grabbing mass shootings, but daily shootings on our city streets.22 Community violence disproportionately impacts urban neighborhoods of color, and particularly young men. Black and Hispanic Americans make up less than a third of the population, but account for nearly three-quarters of all gun homicide victims in the US. Homicide is also the leading cause of death of young Black men.

Third, in recent years a number of incredibly effective solutions to community violence have been developed and implemented in several American cities.23 Many of these strategies address violence through a community-centric, public health lens rather than a traditional criminal justice approach. Cities implementing these solutions have seen remarkable results: in Oakland, California, shootings and homicides dropped by nearly 50% between 2012 and 2018.24

Fourth, there has not been nearly enough investment in these innovative solutions at any level of government, especially at the state and federal levels, and there is no coherent federal policy to support the field of community violence prevention.25 Nationally, our investments in addressing violent crime have almost exclusively come in the form of funding the expansion of suppression-based approaches to violent crime.26 We need to rethink our strategy and invest in comprehensive solutions to community violence with a dedication that more closely matches our approaches to domestic violence, the opioid epidemic, and car accidents.27

This report was created for advocates and policymakers around the country with two express purposes in mind:

1) To provide a better understanding of the landscape of existing federal programs that could be better leveraged to address community violence, with a focus on three programs: the Victims of Crime Act, the Edward Byrne Memorial Justice Assistance Grant Program, and Project Safe Neighborhoods. Since all three of these programs give significant discretion to state agencies in deciding how to allocate resources, directing more federal dollars to effective, community-based violence reduction strategies is often a matter of targeted state and local advocacy. This report identifies past missteps and future opportunities, and describes successful examples of advocacy and investment from different parts of the country.

2) To propose a way to fill the large gaps in existing federal investments. Fundamental system change requires working with what already exists and also charting a course to a new future. Current federal investments to address community violence are completely inadequate, for the reasons that will be discussed in this report. There is no federal agency dedicated to understanding and addressing community violence, as there is for domestic violence. This report recommends the creation of a federal Office on Community Violence, drawing inspiration from the Office on Violence Against Women, and provides an outline of what such an office should look like.

Following the “law and order” philosophy of the Nixon era, from which America has never really departed, federal funding for public safety has almost exclusively been allocated to supporting law enforcement, with very little accountability and oversight. It’s long past time to commit to a federal solution to community violence that emphasizes investment in impacted communities and moves away from destructive law enforcement practices of the past. Community members, advocates, and other stakeholders have been proposing this basic solution for decades. It’s time for America’s leaders to finally listen.

SPOTLIGHT

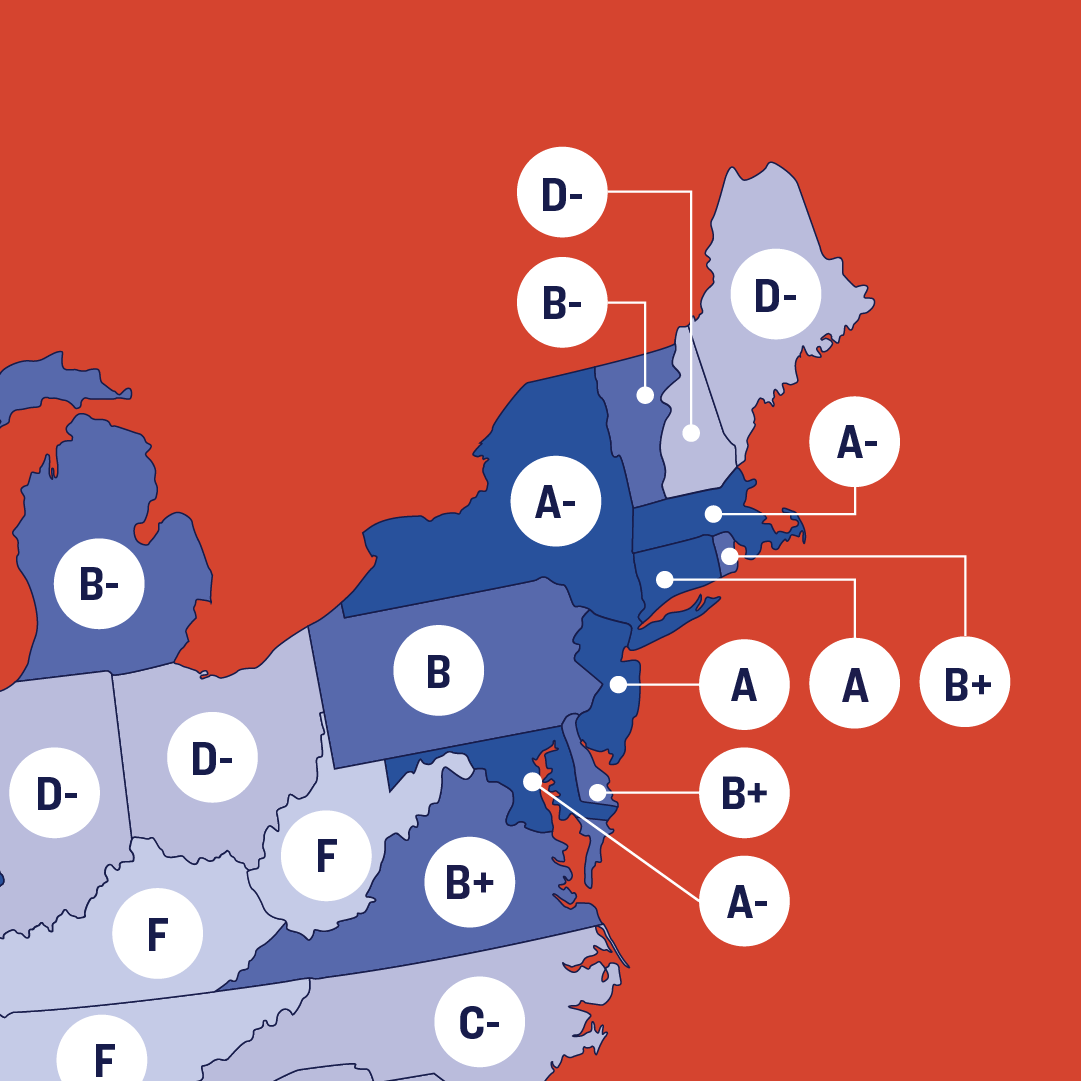

GUN LAW SCORECARD

The data is clear: states with stronger gun laws have less gun violence. See how your state compares in our annual ranking.

Read MoreVictims of Crime Act

In a single moment, a bullet can change everything.

On a fall day in 2017, 16-year-old Taequan was playing pickup basketball on a court next to his home in Richmond, Virginia. Things got physical, tempers flared, and angry words were traded between the teams. After the game, Taequan was hanging out near the court with teammates when a car drove by and shots rang out. Taequan was hit three times.

Taequan found himself in a hospital room at a Richmond trauma center, being treated for gunshot wounds in his leg, hip, and back. Fortunately, Taequan pulled through. But surviving the shooting was just the first hurdle.

Taequan happened to be shot in one of the 30 or so American cities with trauma centers that have implemented hospital-based violence intervention programs (HVIPs). As Taequan lay in his hospital bed, recovering from multiple injuries, he was approached by a case worker from a program called Bridging the Gap.28 During Taequan’s nine-day stay in the hospital, his Bridging the Gap case manager visited him daily, bringing him a number of initial resources, and providing emotional support to him and his family.

A gunshot wound often ripples out into the wider community, and Taequan’s case was no exception. As soon his mother learned of the shooting, she went to the hospital and refused to leave her son’s side. She spent so much time nursing Taequan back to health that she lost her job and started falling behind on rent payments.29 As Taequan transitioned home, still unable to use one of his legs and relearning how to walk, he and his family faced the threat of impending eviction.

Rachelle Hunley, Taequan’s case manager, worked to help his family address this host of new challenges. To deal with the immediate emotional crisis of the shooting, including the fear of moving back to their home, Rachelle referred both Taequan and his mother to mental health services through VCU’s Trauma Psychology Program. She also helped the family gain access to food and successfully apply for food stamps. Working with the Richmond Redevelopment and Housing Authority, Bridging the Gap staff were able to negotiate a plan to avoid eviction, which included helping with back payment of rent and associated fees. The family was also relocated to a new unit in order to help ease fears about returning to their building.

When Taequan was able to return to school, he understandably struggled to focus and acted out. After Taequan was expelled and placed in an alternative school, Rachelle provided him with additional mental health services, including enrolling him in Emerging Leaders, a group program run by Bridging the Gap for young people who have been the victims of serious violence.

“You have to understand, this was not a ‘bad’ kid,” said Rachelle, who is now the Bridging the Gap Network Manager at VCU.30 “This was a kid facing really hard circumstances and he was going through a lot. When a young person gets on the wrong path, people are quick to say ‘it’s their fault, they didn’t make good decisions,’ but that misses important social context. When we identify what’s causing some of those challenges and provide extra help and support, people can choose a different path, and Taequan is an example of that.”31

As he worked through alternative school, Taequan began to show great improvement in his behavior, school work, and self-esteem. Ultimately, he accomplished his goal of returning to high school and, thanks to a partnership between Bridging the Gap, the Mayor’s Youth Academy, and VCU Healthcare Career Pathway, Taequan started an internship program at VCU, where he worked in the patient transportation department and had the chance to shadow doctors, trauma surgeons, and violence prevention professionals.

In 2019, Taequan graduated from high school. As he was trying to figure out what to do next, he was offered a part-time job by the patient transportation department at VCU, where he had made a positive impression as an intern the year before. He continues to dream about working in healthcare as a physical therapist or even as a violence prevention professional, like the staff at Bridging the Gap.32

Taequan at his high school graduation in 2019.

“Despite the challenges he’s faced, he continues to be an incredibly positive person and wants his story to uplift and educate the community,” said Rachelle.33 “He’s been such a success, but it’s crazy to think of all the people like Taequan who aren’t getting the help and services they need.”34

It’s not difficult to imagine a very different outcome had Taequan not received services from Bridging the Gap. In areas of the country where HVIP services are not available, as many as 45% of gunshot victims are shot again within just five years and are at elevated risk of committing violence themselves.35 HVIPs can help break this cycle: studies from around the nation show how HVIPs improve public safety by significantly lowering the risk that participants will be violently re-injured, perpetrate violence, or otherwise become ensnared in the criminal justice system in the years following hospital discharge.

There is still great need to bring effective strategies like HVIPs to scale in America. One federal funding stream that can help accomplish this is the Victims of Crime Act (VOCA). At the time Taequan was shot in 2017, Bridging the Gap was the only HVIP in Virginia. However, a recent investment of nearly $2.5 million in VOCA funds36 has enabled the Virginia Hospital Association to work with VCU and the Health Alliance for Violence Intervention, a national network of HVIPs, to bring programs to nine other hospitals around the Commonwealth.37

Several other states, including New Jersey and California, are also starting to use VOCA money to fund effective programs like HVIPs. Advocates can and should play a major role in speeding up and expanding this progress.

Victims of Crime Act Origins

The idea that crime survivors should receive assistance from the government may sound like a given, but it’s actually a surprisingly recent concept first proposed in the 1950s by English reformer Margery Fry. It wasn’t until 1963 that New Zealand became the first country to pass a law that provided financial reimbursement to victims of crime.38

Around the same time, a movement dedicated to shining a light on the experiences of crime survivors was beginning to build momentum in the United States. It wasn’t enough to punish the perpetrator of a crime, these advocates argued, it was also necessary—and perhaps even more important—to support and directly compensate the victims.

In the words of US Supreme Court Justice A.J. Goldberg, “one who suffers the impact of criminal violence is also the victim of society’s long inattention to poverty and social injustice.”39 But this growing sense that society had an obligation to those whom it failed to protect from crime was not reflected in the country’s laws or policies. State officials, at the urging of crime survivor advocates, realized that political action was necessary to ensure the institutionalization of victim assistance programs.

In 1965, California became the first state to create a system of compensation for victims of crime, soon followed by New York. As this nascent movement gained steam, more and more states created victims’ assistance programs and passed constitutional amendments designed to recognize and protect the core rights of crime survivors. As more states took action, a national victims’ rights movement began to find its voice through the formation of groups like the National Organization for Victims Assistance (NOVA).

In the 1980s, at the urging of groups like NOVA, President Ronald Reagan created the Presidential Task Force on Victims of Crime, which was charged with creating a set of recommendations as to how federal policy could be reformed to better support crime survivors. After holding public hearings around the country, the Task Force published a final report that made the case for the passage of federal legislation that would fund state-level victim compensation and assistance programs.40 This created the foundation for what would become the Victims of Crime Act.

Victims of Crime Act Overview

Enacted in 1984, VOCA created a system of federal grants designed to support the expansion of services for crime survivors.41 VOCA grants are administered by the Office for Victims of Crime, which sits within the Department of Justice.42 For the purposes of this report, the most relevant aspects of VOCA are the state victim compensation and state victim assistance programs.43 To resource these grant programs, VOCA created the Crime Victims Fund (CVF), which is unique in that it is not funded by taxpayer dollars. Instead, CVF is supported by the payment of criminal fines, penalties, forfeitures, and special assessments by individuals and organizations convicted of breaking federal law. A major portion of these payments come in the form of criminal fines paid by large corporations convicted of wrongdoing. In 2017, Volkswagen paid $2.8 billion into CVF in connection with its emissions cheating scandal.44

Over time, CVF has grown exponentially, with a balance of approximately $6 billion in 2020—even as the number of corporations prosecuted for federal crimes annually has steadily declined.45 Each year, Congress establishes a cap on how much may be spent from CVF. For many years, the cap hovered around the $500 million mark, but in FY2015, Congress increased the cap dramatically, up to $2.3 billion—a more than fourfold increase.46 This change was the result of years of advocacy on the part of service providers and advocates across the country who pushed for more CVF dollars to be distributed “in order to more effectively meet the needs of crime victims—especially those who continue to fall through the cracks.”47

Under federal law, a certain amount of CVF funds must be used for a series of programs like the Children’s Justice Act Program, which provides resources to states to improve the handling of cases involving child sexual abuse and exploitation.48 Once these smaller allocations are made, remaining funds are to be divided in the following manner: up to 47.5% to the VOCA state compensation program (in practice, this ends up being much less than 47.5%), at least 47.5% to the VOCA state assistance program (plus any funds remaining after compensation spending obligations are satisfied), and 5% to competitive grants administered at the discretion of the Office for Victims of Crime, for purposes including pilot programs, evaluations, and the provision of training and technical assistance.49

Compensation versus Assistance

While compensation is given directly to individual crime survivors to cover things like medical costs, mental health counseling, lost wages, relocation, and funeral expenses, assistance funds are granted to organizations that serve survivors of crime. In contrast to the onerous and all-too-often unjust individual qualifications for compensation programs, assistance grants only require that organizations serve individuals who are victims of crime. An organization supported by a VOCA assistance grant would not have to turn away a potential client because of an unrelated prior conviction in that client’s record, for example.

Not only are there fewer limitations on assistance grants, there is also much more federal money currently available. The formula that the Office for Victims of Crime uses to award compensation grants is based on how much each state awarded for victims compensation in prior years.50 In practice, this has translated into VOCA compensation awards totaling around $130 million in a given year. Since any funds not spent on compensation may then be spent on assistance, the funds available for assistance grants are significantly greater—especially since the dramatic increase of the CVF spending cap in FY2015. In FY2018, only $129 million was available nationwide for VOCA state compensation grants, compared to more than $3.3 billion for VOCA state assistance grants.51

VOCA State Compensation Grants

All 50 states have compensation programs designed to provide direct reimbursement to individual crime survivors and their families.52 Most state compensation programs have similar eligibility requirements and offer comparable types of benefits.53 Through VOCA’s state crime victim compensation program, the Office for Victims of Crime uses a set mathematical formula to determine the size of award funding for these state-level programs.54

Victim compensation can play a critical role in helping to break cycles of interpersonal violence. As the World Health Organization has recognized: “In addition to physical injury, violence can lead to life-long mental and physical health problems, social and occupational impairment and increased risk of being a victim and/or perpetrator of further violence. Interventions to provide effective care and support to victims of interpersonal violence are, therefore, critical for protecting health and breaking cycles of violence from one generation to the next.”55

Unfortunately, the difficulties survivors face accessing compensation programs are also well documented. In Louisiana in 2016, for example, a total of 149 people were approved for some amount of victim compensation for firearm-related cases, yet that same year, more than 580 people were shot in New Orleans alone. National data indicates that applicants for victim compensation “tend to be female, white, and between the ages of 25 and 59,”56 despite the fact that this does not align with demographic data about victims of crime—particularly victims of community violence, who are disproportionately young men of color.

In many states, racist policies have contributed to unequal access to these resources. As reported by The Trace in 2018, “[w]hile black men disproportionately experience violence, they are also more likely than whites to have been convicted of a felony, which in some states can disqualify people from receiving funds.”57

According to reporting by the Marshall Project, at least seven states, including Florida, “bar people with a criminal record from receiving victim compensation…[and] an analysis of records in two of those states—Florida and Ohio—shows that the bans fall hardest on black victims and their families.”58 Indeed, an investigation in Ohio revealed that “among the thousands of victims in Ohio denied compensation annually, some were rejected because of criminal or drug histories, even if neither played a role in the crime that left them needing assistance.”59 The result of these policies is that family members with clean records are being denied funds to help pay for funeral expenses and other costs related to losing a loved one to a violent crime, just because the deceased person had a criminal conviction in their record.60

At the national level, from 1993 to 2009, only nine percent of victims of serious violent crime received compensation from a victim services agency.61 This systemic racism—in the form of a criminal justice system that disproportionately arrests and convicts people of color for low-level offenses,62 combined with draconian laws that deny compensation to victims and their families based on the victim’s criminal history—makes it much more difficult for crime survivors to access services that can help interrupt devastating cycles of violence.

Gun violence prevention advocates and policymakers should seek to understand the obstacles that survivors of violent crime and their families are facing in each state and push for reforms to remove those obstacles. Additional resources are available from organizations like the Alliance for Safety and Justice, which recently supported AB 767 in California, a first-of-its-kind bill that would help “eliminate barriers to victim compensation faced by victims of police brutality and other violent crimes.”63

VOCA State Assistance Grants

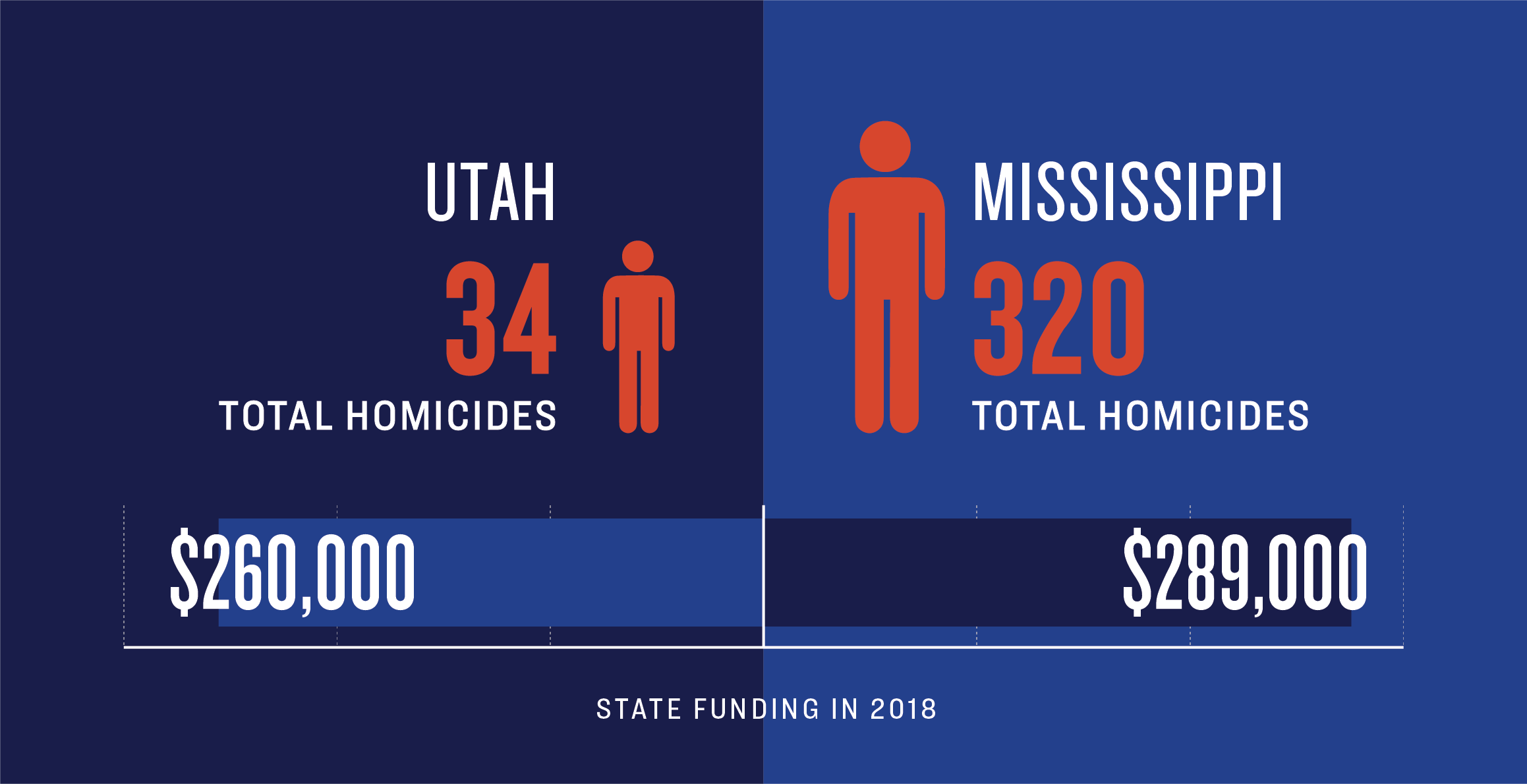

Each year, the Office for Victims of Crime also awards VOCA assistance grants to every state. These grants are in turn passed through to government agencies as well as public and private nonprofit organizations that provide services to victims of crime.64 Each state receives a baseline of $500,000 for the victim assistance program and that figure is then adjusted based on population, sometimes quite significantly, with the nation’s most populous state, California, receiving more than $260 million in 2019.65

VOCA assistance grants may be used to fund services for crime survivors that respond to their immediate emotional, psychological, and physical needs, including assisting survivors with stabilizing their lives, facilitating survivor participation in the criminal justice system, helping survivors access victim compensation, connecting them with mental health services, and working to help restore their sense of security and safety.66 Other qualifying services include peer support, relocation, legal assistance, and transitional housing.67 Many of these services touch directly on the underlying root causes of interpersonal violence.

VOCA assistance grants are awarded to state administering agencies (SAAs), which are designated by each state’s governor and therefore vary from state to state. The SAA in Virginia, for example, is the Department of Criminal Justice Services, while in California it’s the Governor’s Office of Emergency Services, and in New Jersey, the Office of the Attorney General.68 A directory of SAAs is maintained by the National Association of VOCA Assistance Administrators.69

Federal law gives SAAs enormous discretion to decide how to award assistance grants, including discretion over which agencies and organizations will receive funding and how much each receives.70 Federal regulations require SAAs to allocate at least 10% of their victim assistance funds for grants to serve each of the following groups: (1) victims of sexual assault (2) victims of domestic abuse (3) victims of child abuse and (4) underserved victims of violent crime.71 For the purposes of the fourth category, states have discretion to choose the crime type and/or demographic characteristics of crime victims that qualify as “underserved.” In 2016, the Office for Victims of Crime gave examples of victim populations “often underserved,” including the families of homicide victims, survivors of gang violence, and victims of violent crime in high crime urban areas.72

After the initial 40% is allocated according to the four categories laid out above, SAAs may then allocate the remaining 60% at their discretion to any entities that are eligible for funding under VOCA.73 Although there are a variety of general requirements—including being a public or nonprofit organization, serving victims of crime, and matching 20% of VOCA-provided funds, among others—essentially any public agency or nonprofit organization that provides direct services to victims of crime may be funded with VOCA assistance grants.74

The earmarking of VOCA state assistance grant funds for underserved victims of violent crime, coupled with a large increase in the spending caps in FY2015 should have translated into a significant increase in resources for organizations serving survivors of violent crime. But the unfortunate reality is that many states are leaving money on the table.

As a report by Everytown and Cities United describes, “As of February 2018, states collectively had nearly $599 million remaining of their fiscal year 2015 victim assistance allocations….As of April 2019, 12 states had failed to draw down any of their fiscal year 2017 victim assistance funds, and all states had a collective balance of 80 percent of their fiscal year 2017 victim assistance funds. If states do not spend down their annual allocation within four years, the funds are returned to the Crime Victims Fund.”75

In the past year, advocates in states including New Jersey, Virginia, and California have had success making the case for VOCA funding to be allocated to hospital-based violence intervention programs. To illustrate what this looks like in practice, the next section of this report provides a detailed look at New Jersey.

New Jersey Case Study

In 2019, New Jersey used $20 million in VOCA assistance funding to create the New Jersey Hospital-Based Violence Intervention Program (NJHVIP), with the express purpose of “enhancing services to underserved victims and victims of gun violence in an effort to break the cycle of repeat victimization and save human lives.”76 Prior to this VOCA-funded expansion, New Jersey had just a single HVIP.77 With the help of VOCA funding, programs are now being implemented in eight other hospitals serving cities disproportionately impacted by gun violence.

In addition to being a remarkable achievement in terms of the sheer size and ambition of the investment, the story of NJHVIP is also a useful case study in the critical role advocates can play in unlocking VOCA funds. In the years leading up to the launch of NJHVIP, the New Jersey Chapter of Crime Survivors for Safety and Justice,78 a flagship project of the Alliance for Safety and Justice,79 had been advocating for greater investment in survivor-centered approaches to addressing violent crime.

New Jersey advocates started to gain traction on these issues when, in part as a result of their work, an article was published in the New Jersey Star-Ledger on August 28, 2018, explaining the connection between victimization and future violence and underscoring the subpar support systems for violence survivors, especially in underserved communities of color—despite the existence of untapped VOCA funds.80

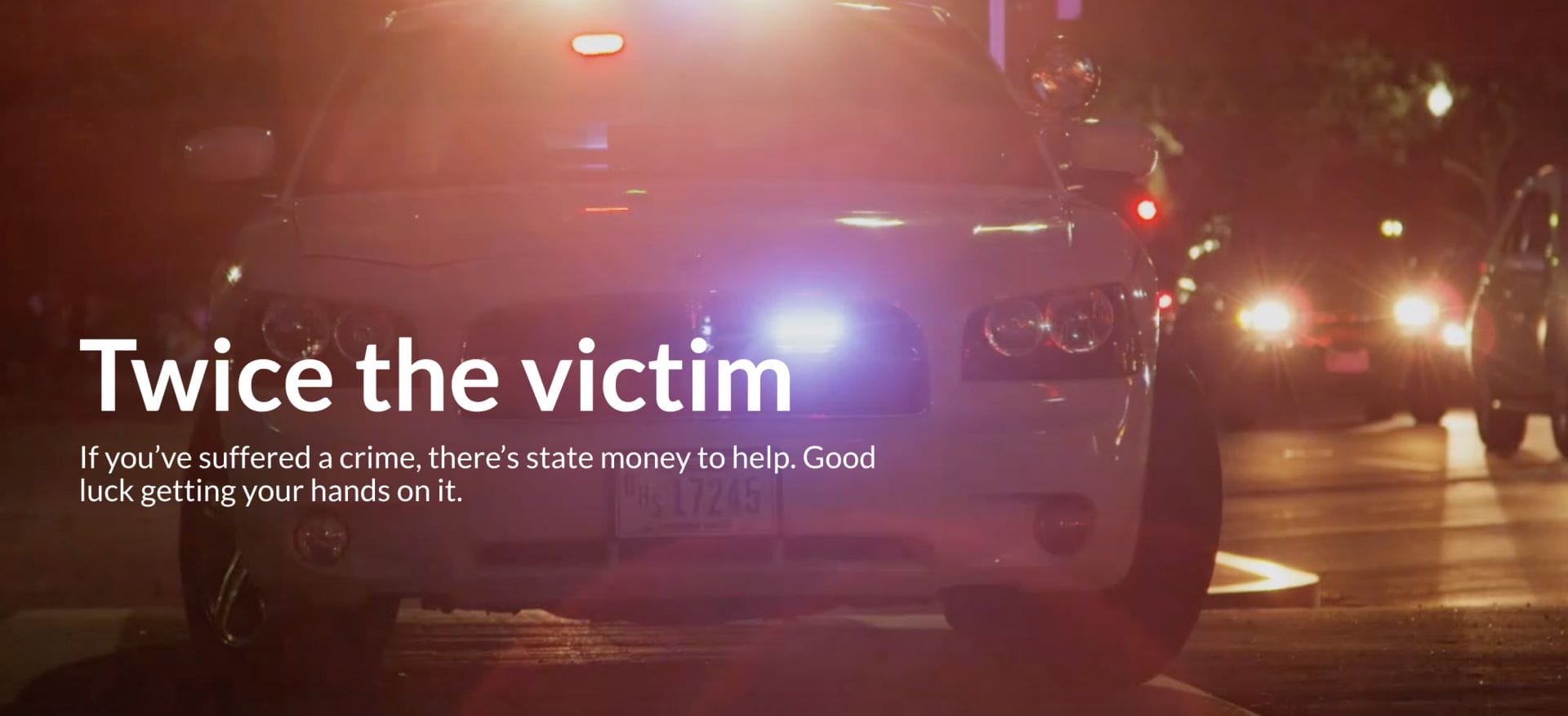

“Twice the Victim,” by Ted Sherman, NJ Advance Media for NJ.Com

The article’s subtitle summed up the situation bluntly: “If you’ve suffered a crime, there’s state money to help. Good luck getting your hands on it.” The investigation showed the extent to which New Jersey was leaving VOCA compensation money on the table, returning nearly $400,000 in unused funds to the federal government in 2017 and failing to distribute $3.4 million of available relief for crime survivors.81

“For people who live in the inner city, often the only support they are going to get is the victims’ comp agency. That is their only chance at hope,” an advocate with Crime Survivors for Safety and Justice told reporters. “It would be one thing if there was no money available, but there is money available. They don’t even spend all their money.”82

New Jersey crime survivor advocates also criticized the way that the assistance program was being managed, pointing out in the Star-Ledger article that most federal victim assistance money was going to county prosecutors’ offices, law enforcement agencies, and sexual assault and domestic violence nonprofit service providers, with “little done to support services for families of homicide victims or to organizations operating in communities of color.”83

As the Star-Ledger article helped draw public attention to these issues, Crime Survivors for Safety and Justice also created an online petition requesting that the governor and the attorney general direct more VOCA funds to services for victims of gun violence. In particular, the group called for an investment of VOCA dollars in HVIPs and Trauma Recovery Centers, inspired in part by the success of a Newark-based HVIP that helped contribute to a 38% decline in homicides between 2013 and 2018.84

New Jersey Attorney General Gurbir S. Grewal listened to the concerns of crime survivor advocates and committed to finding ways to support survivors of community violence. “We have to do more,” he said in the 2018 Star-Ledger article. “If we can get more money to more victims, that’s what we’re committed to doing. And part of that’s going to require more awareness that these pools of money are out there.”85

In early 2019, the attorney general started to make good on this commitment by hiring Elizabeth Ruebman, a crime survivor and a leading advocate for crime victim compensation reform, to become the AG’s Special Advisor on Victims Services, with a mission to “conduct a ‘top-to-bottom’ review of New Jersey’s victim programs and services.”86 Around this same time, a variety of local, state, and national violence prevention organizations, including Giffords, began publicly advocating for the passage of a package of bills designed to support and expand community-based violence intervention and prevention programs, such as HVIPs.87

Source

Tina L. Cheng, et al., “Effectiveness of a Mentor-Implemented, Violence Prevention Intervention for Assault-Injured Youths Presenting to the Emergency Department: Results of a Randomized Trial,” Pediatrics 122, no. 5 (2008): 938–946.

On September 24, 2019, Attorney General Grewal announced the availability of $20 million in VOCA funding to establish eight new hospital-based or hospital-linked violence intervention programs in New Jersey.88 “This initiative will advance two of our top priorities—reducing gun violence and improving services to victims,” the attorney general said. “These hospital-based violence intervention programs have shown that there is more than one way to save lives at a hospital. You can save lives by healing gunshot wounds, and you can also save lives by changing lives and turning them away from violence.”89

Governor Murphy also supported and applauded this move: “Hospital-based violence intervention programs have a proven track record of reducing gun violence and strengthening ties between public health facilities and the populations they serve,” he said at a press conference. “With today’s funding, we are taking another step to combat gun violence by tackling its root problems.”90

The official Notice of Availability and Award of Funds released by the Office of the Attorney General laid out two specific purpose areas: (1) the funding of up to nine demonstration sites implementing the HVIP strategy as a partnership between a health facility and one or more community-based organizations and (2) funding for a single, statewide training and technical assistance provider with an understanding of the “range of crime victims’ needs in both institutional and community settings,” to support the nine demonstration sites.91

Each applicant was eligible to apply for an award of up to $2 million and another $2 million was reserved for training and technical assistance. Per federal VOCA requirements, a 20% match was required of applicants, although a match waiver could be obtained on a case-by-case basis in situations of documented need. The grant period was set at 21 months, running from January 1, 2020 to September 30, 2021. At more than $10 million of funding per year, NJHVIP represents a significant state investment in the expansion of violence intervention infrastructure.92

Grantees were selected through a competitive process in which each applicant was evaluated on several criteria, including: (1) experience and capabilities (2) a needs assessment (3) goals, budget, and work plan (4) equitable partnership between medical facilities and community groups (5) culturally appropriate victim services (6) a plan for referrals to other programs to help meet victim needs and (7) data collection and performance measurement.93 Selections were made and awardees notified of the results before the close of 2019.

On January 29, 2020, former Congresswoman Gabby Giffords joined Governor Murphy and Attorney General Grewal in Jersey City to publicly announce the awards.94 In total, eight new sites received funding to implement an HVIP in hospitals in the New Jersey cities most disproportionately impacted by gun violence. Newark was also granted funds to expand its existing program.95 The attorney general announced that the Health Alliance for Violence Intervention (the HAVI),96 a national network of HVIPs, had been selected as the state’s technical assistance provider.

Fatimah Loren Dreier, executive director of the HAVI, accurately described NJVHIP as a “monumental step” for New Jersey.97With this award, the state of New Jersey became one of the first states in the nation to invest directly in HVIPs using VOCA funding. This was also the first time in New Jersey’s history that the Garden State specifically invested in this evidence-based violence reduction strategy.

As of the writing of this report, all NJHVIP sites are engaged in a planning process, and three have begun actively providing intervention services to shooting victims and survivors of other forms of serious violence. All sites are expected to be up and running by the end of 2020, with ongoing technical assistance being provided by the HAVI.98

New Jersey is at the forefront of a growing movement. In May 2019, Virginia Governor Ralph Northam announced a nearly $2.5 million investment of VOCA funds to support the implementation of HVIPs at seven Virginia hospitals.99 Other states, including Connecticut,100 California,101 Missouri,102 New York,103 and Ohio,104 have taken similar promising steps in recent years.

From left: Dr. John Rich, Fatimah Loren Dreier, Governor Murphy, and Dr. Ted Corbin.

While this report is focused on HVIPs, some states have begun supporting violence intervention strategies outside of the hospital setting as well. In New York, for example, the Office of Victim Services directed millions of dollars of VOCA funding in 2019 to support the state’s SNUG program, a street outreach strategy in which credible messengers work with a team of social workers and other providers to intervene with high-risk individuals.105 Despite these encouraging developments, there is still great need to increase the speed of this progress and a tremendous opportunity for advocates to help make that happen.

Leveraging VOCA Funding

This section covers takeaways, lessons learned, and key resources for stakeholders in states around the country. First and foremost, stakeholders should take steps to ensure that practitioners themselves are aware of and well positioned to successfully apply for VOCA assistance grants.

Raising Awareness and Building Capacity to Leverage VOCA

Many organizations that provide critical services to crime survivors in underserved areas are extremely busy doing lifesaving work and may not know about the opportunities presented by VOCA assistance grants. Other organizations focused on policy and education can help by spreading the word and directing practitioners to existing resources.

For instance, in 2018, Giffords partnered with Equal Justice USA and the Healing Justice Alliance to produce a webinar designed for managers of HVIPs.106 This 90-minute presentation, which is available for free online, lays out why HVIPs are a good fit for VOCA assistance grants and includes practitioners from Detroit talking about their experience applying for VOCA funding. The webinar also introduces an incredibly important resource for practitioners: a toolkit by Equal Justice USA called “Apply for VOCA Funding,” which gives step-by-step instructions on accessing these funds.107

From a practitioner perspective, one of the drawbacks of VOCA is that it requires a substantial amount of time and resources to manage. A report by Everytown and Cities United recommends that practitioners look to partner with larger institutions, like city agencies, to help address this challenge.108 In addition to city agencies, larger nonprofits, universities, hospitals, and other stakeholders with developed grant application infrastructures can also play this role. In New Jersey, for example, the NJHVIP program allows a hospital or other eligible medical facility to be the “lead applicant,” which manages administrative aspects of the grant while community partners and hired staff carry out the intervention work.109

Gun violence prevention organizations in particular should take the opportunity to build relationships with nearby community-based practitioners doing lifesaving work and help connect them with resources to better understand and leverage VOCA. The HAVI maintains a membership directory of HVIPs, which is a good starting point for identifying existing programs.

Several states have started creating VOCA assistance grant programs that are specifically targeted to organizations doing violence intervention work, as was the case in New Jersey and Virginia in 2019. This is the most direct way to expand violence intervention work, since applicants don’t have to compete against all other categories of service providers as they would with a more generalized VOCA assistance solicitation.

Building Relationships with VOCA State Administering Agencies

A vital step for stakeholders interested in leveraging VOCA dollars is to identify the relevant VOCA state administering agency (SAA). The National Association of VOCA Assistance Administrators has an easy-to-use directory available here.110 As mentioned above, the SAA is different in every state, and each has a unique process for awarding VOCA assistance grants.

After identifying the relevant SAA, the next step should be to conduct research to understand the VOCA assistance grant landscape within the stakeholder’s state. We recommend that advocates consult the CSJ toolkit, which provides a series of questions that will help them better understand this landscape.111 In many cases, the answers to such questions will lie with the SAA, so it is important for advocates to reach out and build relationships. To help SAA staff understand the needs of the community, it may be most effective to actually invite them to visit a program that advocates want to expand through VOCA.112

In New Jersey, advocates built such a strong relationship with their SAA, the Office of the Attorney General, that one of the leaders of the statewide crime survivors movement was hired to join the Office as the Special Advisor on Victims Services.113 In many cases, SAAs are staffed by individuals who are committed to making a difference and who will likely be open to community input about potential ways to use VOCA assistance grants.

Making the Case to State Administering Agencies

Convincing government agencies to break from the status quo often requires both persuasion and persistence. Fortunately, there are a number of excellent resources for advocates to help make this case in a compelling manner.

First, CSJ emphasizes that “advocates should not assume that administrators fully understand the racial disparities that exist in current VOCA funding priorities. Make sure to share studies that drive home this point.”114 Next, advocates need to make the case for why strategies like HVIPs are a good use of VOCA funding. To this end, the HAVI has produced an excellent white paper designed to introduce stakeholders to the HVIP strategy.

SAA staff are often more likely to embrace an idea if it’s already been implemented in another state. Stakeholders should help their SAA staff understand that, by funding evidence-based services for victims of serious violence in underserved communities, they will be joining a larger movement of SAAs that are doing the very same thing. Everytown’s report A Fund for Healing contains helpful case studies of VOCA funds being used to support violence intervention programs in states like Connecticut, Pennsylvania, Missouri, Massachusetts, Illinois, and New Jersey.115 Examples of Requests for Proposals from other states, such as the one released by New Jersey’s Office of the Attorney General to solicit applicants for NJHVIP,116 can serve as helpful templates for SAAs seeking to implement something similar for the first time. Giffords is in regular touch with many of these SAAs and is available to connect stakeholders with SAA staff who can share more about their experiences and lessons learned.

HERE TO HELP

Interested in partnering with us to draft, enact, or implement lifesaving gun safety legislation in your community? Our attorneys provide free assistance to lawmakers, public officials, and advocates working toward solutions to the gun violence crisis.

CONTACT US

It’s also worth noting that Congress itself has encouraged this use of VOCA funds. Congressional appropriators stated in a committee report for FY2019 that Congress “is aware that hospital-based violence intervention has shown effective results in preventing injury recidivism for victims of violent injury, and encourages States to consider utilizing funding provided through the Crime Victims Fund to establish or expand hospital-based intervention programs.”117 This language was specifically highlighted in the Office for Victims of Crime’s solicitation for VOCA assistance grants,118 and the office has also used its discretionary funding to support eight demonstration sites to “expand the use of hospitals and other medical facilities as an entry point to increase support for victims of crime, improve their outcomes, and prevent chances for repeat victimization.”119

In making the case to SAAs, it’s also helpful to present the context of the overall problem that needs to be addressed and how VOCA funding can be a meaningful part of the solution. In a 2018 advocacy memorandum to the governor of Virginia, Giffords attorneys outlined the toll that interpersonal gun violence takes on Virginia, a toll that falls disproportionately on communities of color. The Giffords statistics library offers a comprehensive state-by-state analysis of gun violence that may be helpful in making this case, and Giffords attorneys are available to answer questions as advocates prepare similar memos.

If after an initial round of communication, an SAA appears unwilling or unable to act, advocates should consider longer-term options, including working to engage the media. The CSJ toolkit recommends that advocates pitch VOCA-related stories to local reporters; leverage media coverage through events linked to high-profile periods of recognition, such as National Crime Victims’ Rights Week in April; and write letters to the editor and opinion pieces for publication.120

Forming strategic partnerships with other groups or individuals may also be helpful to achieving VOCA-related advocacy goals. If a critical mass of interested stakeholders exists, forming a coalition is a powerful way to pool resources and increase influence beyond the footprint of a single organization acting alone. Giffords organizes such a coalition in California, which is focused on increasing resources for organizations doing violence intervention work, and provides updates to members on VOCA-related funding opportunities.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, during the entire advocacy process all stakeholders should strive to center the voices of crime survivors. Every effort should be made to work directly with survivors on both an individual and organizational basis to craft an advocacy agenda and to determine the way it will be presented. Letters and testimonials from crime survivors shared both in private meetings and public settings can be one of the most effective methods for convincing SAAs to try a new approach.

Reforming VOCA at the Federal Level

In addition to pushing for change at the state level, advocates should prioritize structural changes to VOCA at the federal level. As a federal statute, VOCA can be amended through the legislative process and, in fact, has been changed several times since 1984 to support victims of child abuse and terrorist attacks, and to allow for discretionary grants to private organizations.121 Changes can also be made to the federal regulations governing the implementation of VOCA, which has happened several times over the life of the program.

Giffords recommends the following policies and reforms to better position VOCA to provide services to victims of violent crime and their families.

Protect the Long-Term Sustainability of the Crime Victims Fund

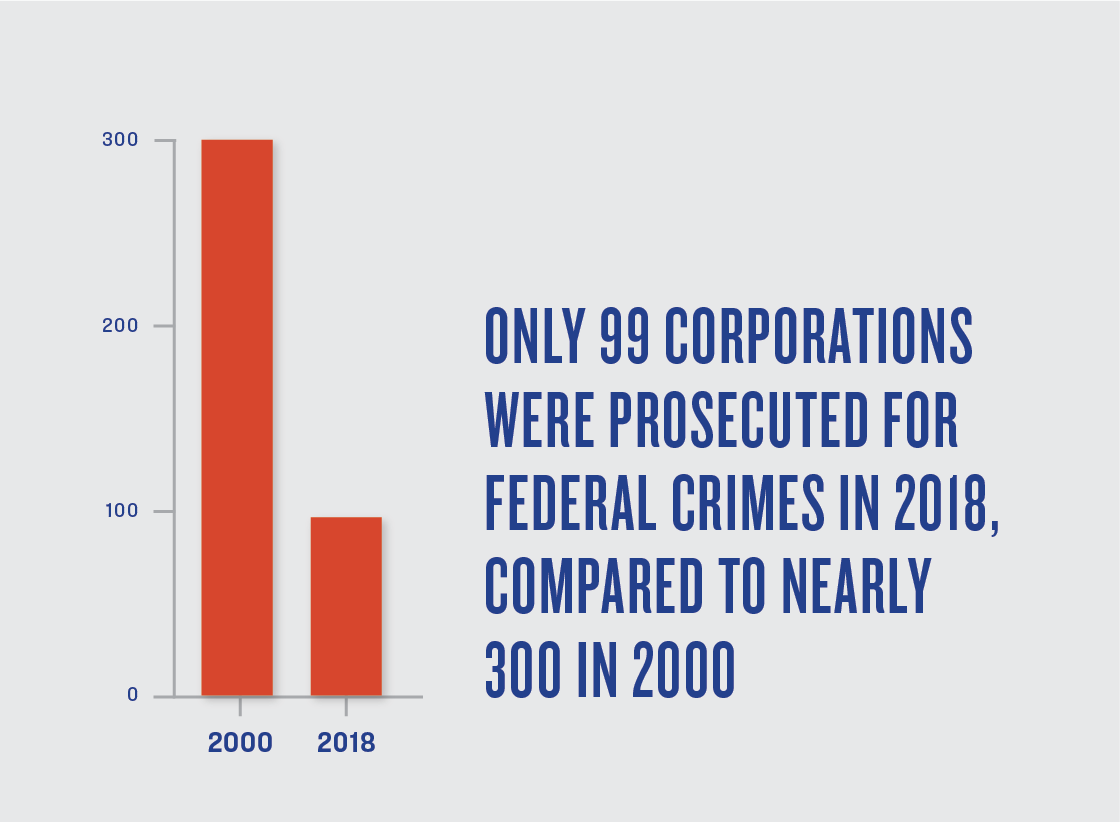

The spending cap increase authorized by Congress for fiscal year 2015 represents an opportunity, but also a challenge to the sustainability of the CVF itself. Since the initial cap increase, the spending cap has fluctuated widely each year. Between FY16 and FY20, the spending cap was as high as $4.4 billion and as low as $2.5 billion. Meanwhile, revenues for the CVF have steadily declined as prosecutions against major corporations have dropped122—only 99 corporations were prosecuted for federal crimes in 2018, compared to nearly 300 in 2000.123 The overall size of CVF peaked in FY17 at $13 billion, and as of FY20 was closer to $6 billion, a more than 50% contraction.

Moreover, as a recent letter to Congress signed by 56 state and territory attorneys general pointed out, “Over the last decade, the Department of Justice has increasingly utilized deferred and non-prosecution agreements to resolve cases of corporate misconduct. These agreements bypass the traditional prosecution process and shift fines and penalties into the general treasury rather than the Fund.” In recent years, recoveries from these agreements have been significant: as much as $8 billion per year. As the attorney generals recommend in their letter to Congress, “Redirecting these deposits will provide increased funding to [CVF], which will allow for better predictability of state awards.”124

In addition, the National Association of VOCA Assistance Administrators recommends that Congress create a more stable spending cap, so that states and their grantees will have a better sense of the year-over-year funding that will be available through CVF and VOCA. While such a cap is a good idea in order to maintain stability, given the enormous needs of crime victims around the country, such a cap should be set no lower than FY2017 levels of $2.5 billion.125

Given the importance of VOCA and CVF in supporting survivors of violent crime and their families, violence prevention advocates and their allies must continue to monitor this situation and impress upon federal leaders the importance of maintaining the sustainability of the CVF, even if that means starting to support it with general fund dollars. By reprioritizing the prosecution of corporate wrongdoing, amending federal law to direct recoveries from deferred and non-prosecution agreements to the CVF, and taking the other steps outlined above, Congress and the Biden administration can help ensure the longevity of this critically important federal funding source.

Increase the Percentage of Funding Earmarked for Underserved Crime Victims

The Office for Victims of Crime has noted that “victims of gang violence,” “victims of violent crime in high crime areas,” “victims of physical assault,” and “survivors of homicide victims,” are all often underserved.126 However, as discussed above, many states have typically not used VOCA victim assistance funds to meaningfully invest in programs that work with underserved victims of serious violence.

To address this, the Office for Victims of Crime should draft and publish a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, followed by a Final Rule that will increase the minimum percentage of funding allocated for services assisting underserved victims of violent crimes to at least 15 percent. Presently, SAAs are required to allocate a minimum of 10 percent of each year’s VOCA victim assistance grant to programs and projects specifically serving this population. Increasing the percentage allocated for such programs will help direct funds to community programs serving victims of gun violence.

In 2018 there was nearly $599 million in untouched VOCA victim assistance funding from the 2015 distribution, suggesting that ample funds exist to expand services for underserved crime victims without taking funds away from other types of crime survivors.

Clarify That VOCA Assistance Funds May Be Used to Support “Crime Prevention” Services

The line between “crime prevention” and other forms of services for crime victims is incredibly blurry. Taking HVIPs as an example, providing wraparound services for victims of violent crime is both a way to help address the trauma and needs of the individual victim and likely to help prevent future acts of violent crime. At present, the Office for Victims of Crime (OVC) website states that “Services such as…crime prevention activities cannot be supported with VOCA victim assistance funds.”127 As long as OVC maintains that crime prevention activities cannot be supported by VOCA assistance grants, community violence organizations will have to work to fit a square peg into a round hole by not acknowledging the preventative effects of their work, which may have the unintended consequence of discouraging such organizations from applying for VOCA assistance grants.

Moreover, this position does not appear to be in line with current federal regulations. Federal guidelines governing VOCA did explicitly include “crime prevention activities” among the list of “expressly unallowable sub-recipient costs” in 1997, and again in proposed guidelines in 2002 and 2013.128 However, in final regulations adopted in 2016 and effective as of August 8, 2016, “crime prevention activities” is no longer among the list of prohibited activities.129 Despite this, the OVC website and many state-level VOCA assistance solicitations continue to reference this now-deleted prohibition, creating ongoing confusion.130

OVC should clarify that VOCA state assistance grants may be used to fund programs that prevent crime through the provision of services to crime victims.131 To bring additional clarity to this issue and to encourage the use of VOCA funds for programs that address community violence, the Office for Victims of Crime should also add “community violence intervention programs” to the list of direct services for which VOCA victim assistance funds may be used at 28 CFR § 94.119.

SPOTLIGHT

GUN VIOLENCE STATISTICS

Explore facts, figures, and original analysis compiled by our experts. To end our gun violence crisis, we need to better understand where, how, and why violence occurs.

Learn MoreByrne JAG

When Jerome Brown was just five years old, he lost his father in an armed robbery.132 Jerome’s nephew was shot and killed at age 17. Jerome’s brother was shot while assisting Jerome in his job as a bouncer at a nightclub—left permanently paralyzed by someone who was upset about his friend not getting into the club. Jerome provides regular care for his brother to this day.

Jerome himself has been shot on three separate occasions: twice during his younger years, while he was still stuck in the gang lifestyle, and then later as a violence intervention worker, when he was shot through the shoulder as he tried to stop a retaliatory shooting on the streets of Buffalo, New York.

“Gun violence has impacted my life more than anything else,” said Jerome, who is now the director of a gun violence intervention and prevention program known as 518 SNUG in Albany, New York. “I think every day about what I’ve lost that I can never get back. I can’t change it. But having gone through what I’ve gone through, I have credibility and can offer validation to guys out on the street that it’s possible to be where they are and turn things around like I did.”133

SNUG, a statewide initiative operating in 12 sites around New York with direct support from the legislature and governor, is modeled after Cure Violence, a public health approach to reducing community violence. The SNUG strategy involves identifying individuals at highest risk of engaging in violence and then building relationships with them using trained credible messengers, known as street outreach workers, who work to address risk factors, mediate potential conflicts, and steer their clients towards a different way of life.

Jerome and other outreach workers in Albany. Elijah Cancer, front right, was shot and killed while attempting to defuse a conflict in 2018.

Now in his 40s, Jerome works with young men on the streets of Albany, which reminds him of his own experience growing up in New York in the 1980s. “It used to be you couldn’t go four blocks without running into some kind of community center, a location that provided mentoring and positive opportunities,” Jerome said. “During the Reagan years, the funding for those things dried up, and suddenly there were no sources of positive influence if you didn’t already have that at home. The only thing left to encourage you was the drug dealers and the gangbangers. Then you had the introduction of crack cocaine in the neighborhoods and you know how that story goes.”134

What turned things around for Jerome was the simple but powerful revelation that other options existed. “If I had a mentor as a teenager, it could have changed things,” Jerome said. “I see that with the guys we work with now. A lot of times, when we help to mediate a conflict, that’s the first time people have experienced positive support—they didn’t even know it was possible. Just knowing that it’s possible makes all the difference in the world.”135

As a gang member, Jerome was often the voice of reason, preventing shootings, calming down angry friends, and stopping conflicts from escalating. When he learned from his cousin about SNUG’s work in Buffalo, he immediately showed up to volunteer. “That’s when I found my calling and my purpose,” he recalled. Jerome eventually took a full-time position as a street outreach worker in June 2014, two years after being released from prison. He has since worked his way up to being a site manager in Buffalo and now in Albany, and is a master trainer for the state.

Jerome’s story is deeply inspiring, but not uncommon at SNUG, where 65–70% of the paid staff are formerly incarcerated individuals who draw on their personal experiences to help put clients on a different path.136 The work that SNUG is doing isn’t police work, but from Jerome’s perspective, is just as essential to creating safe communities. Where traditional policing is typically reactive in nature, responding only once a violent crime has already been committed, SNUG presents an approach to public safety that’s preventative.

Jerome’s SNUG team doubled in size from four frontline workers to eight by November 2018. By the end of 2019, the impact of their work was apparent: injury shootings in the target area had dropped by nearly 25% from 2018 levels. “If you think about the cost of a single homicide being around $400,000 and the fact that a small SNUG site costs just $300,000 per year to operate, we only have to prevent a single homicide to pay for ourselves,” said Jerome. “And we know we’re preventing much more than one shooting each year.”137

Indeed, a number of evaluations demonstrate that SNUG and similar public health strategies have helped lower shootings in neighborhoods in New York and around the country.138 After several years of investing in the expansion of SNUG and similar gun violence reduction strategies, New York State’s gun homicide rate—already very low by US standards—has declined significantly since 2010139 as the overall US homicide rate has been increasing. 140

Jerome sees daily how SNUG complements and enhances law enforcement efforts to improve public safety. “Working together was a hard sell for both sides,” he admits, “but we have very clear limitations on how we cooperate, and information only flows in one direction…Without us, the police have to just wait around for a shooting to happen before taking action. With SNUG there are more options on the table.”141

SNUG’s expansion in New York was funded in part through the Edward Byrne Memorial Justice Assistance Grant Program (Byrne JAG), the federal government’s leading source of support to states and localities to assist them in addressing crime. While Byrne JAG has largely supported “traditional” law enforcement-related needs such as increasing prosecutions, purchasing equipment, and implementing drug task forces, there is ample room within the program to support alternative, community-centric strategies like SNUG. It will take intentional advocacy at the local, state, and national levels to help move Byrne JAG in a better direction—one in which communities are made safer without relying on heavy-handed law enforcement tactics.142

Byrne JAG Origins

For decades, the US federal government largely left issues of crime control to local and state authorities. As crime levels began to increase in the 1970s and 1980s,143 Congress created several new funding streams designed to support state and local crime-fighting efforts, primarily through investing in law enforcement and later, the “war on drugs.”144

Two of the most prominent funding programs were the Local Law Enforcement Block Grant and the Edward Byrne Memorial Formula Grant.145 Both directed federal funding to local and state jurisdictions based on mathematical formulas connected to population size and the proportion of violent crimes in a given jurisdiction. Between the two programs, there were nearly 30 different categories for which local and state grantees could use this funding, ranging from hiring and training personnel to purchasing equipment and making technology improvements.

In 2005, Congress attempted to streamline this grant system by combining these programs into the Edward Byrne Memorial Justice Assistance Grant Program (Byrne JAG), and consolidating the number of purpose areas from 30 down to the following eight: (1) law enforcement (2) prosecution and courts (3) prevention and education (4) corrections and community corrections (5) drug treatment and enforcement (6) planning, evaluation, and technology improvement (7) crime victim and witness (other than compensation) and (8) mental health, including behavioral programs and crisis intervention teams.146

Federal law states that Byrne JAG funding is for use “by the State or unit of local government to provide additional personnel, equipment, supplies, contractual support, training, technical assistance, and information systems for criminal justice” including for any one or more of the eight primary purpose areas.147 It’s important to note that “criminal justice” is broadly defined by federal statute as not just the enforcement of criminal laws, but also “activities pertaining to crime prevention,” including, but not limited to, “programs relating to the prevention, control, or reduction of narcotic addiction and juvenile delinquency.”148

Congress purposefully was not very prescriptive about how Byrne JAG funding may be used,149 which creates an opportunity for stakeholders who support a more community-centric approach to crime reduction. As a recent report from the Center for American Progress notes, “beyond these headings, there is virtually no guidance for how JAG dollars can and should be spent. Jurisdictions can and have used JAG to advance evidence-based approaches to public safety and justice reform, but providing maximum flexibility to states more often results in the perpetuation of existing structures over systemic change.”150

Byrne JAG Overview

Funding for Byrne JAG fluctuates each year, averaging $461 million per fiscal year since Congress started appropriating funding for the program in FY2005. Money is distributed directly to state and local governments using a mathematical formula based half on population size and half on levels of violent crime per the FBI’s Uniform Crime Report. The Byrne JAG formula directs 60% of a given state’s award to the state itself, with the other 40% reserved for local governments, such as cities.151

Byrne JAG grants are one-time awards that are generally given for a four-year period. For a grant made on October 1, 2020, funds would be available, unless spent, until September 30, 2024. In federal fiscal year 2019, there was $263.8 million available through Byrne JAG (approximately $181.1 million to states and territories and $82.7 million to local units of government) and more than 1,100 local jurisdictions and 56 states and territories eligible for funding.152

The governor of each state designates a state administering agency (SAA) to both apply for and administer Byrne JAG funding. The SAA is different in each state: in California, for example, the Byrne JAG SAA is the Board of State and Community Corrections,153 while in Virginia, it’s the Department of Criminal Justice Services.154 Although SAAs are often agencies with a law enforcement function, this doesn’t have to be the case: in Washington State, the SAA is the Department of Commerce.155

Each year, the Bureau of Justice Assistance releases a Byrne JAG solicitation, to which eligible state and local units of government respond in order to demonstrate their eligibility to receive funds. The most recent state solicitation, for example, requires SAAs to submit a program narrative that describes the crime issues facing the state, the SAA’s crime reduction strategy, and an overview of the specific programs that will be implemented with Byrne JAG funding.156

Applicants must also describe their process for “engaging stakeholders from across the justice continuum and how that input informs priorities” with an emphasis on “how local communities are engaged in the planning process.”157 Finally, applicants are required to include a detailed budget proposal, document all anticipated costs, and a plan for gathering and analyzing “specific performance data that demonstrate the results of the work carried out.”158

State and local recipients of Byrne JAG funding have the option of passing resources through to subrecipients. Although the program is considered a resource for law enforcement, it’s critical to note that subrecipients may include community-based organizations or other non-law enforcement entities that work to improve public safety.159 For example, New York’s SAA directed Byrne JAG funding to SNUG, a statewide street outreach program, by using Byrne JAG funds to hire SNUG’s statewide director and its statewide training director.160 In 2019, Virginia’s SAA released a solicitation to Byrne JAG subrecipients that specifically called for organizations to implement “evidence-based programs aimed at reducing gun violence in a targeted community.”161

However, these examples are relatively rare exceptions to the way Byrne JAG funding has been used to date. Byrne JAG funding has disproportionately supported the hiring of law enforcement personnel to engage in suppression and corrections activities, such as drug and gang task forces, with dubious results, while community-based crime prevention strategies have received very little support.

Byrne JAG presents “one of the best opportunities to align law enforcement tactics to the twin 21st-century criminal justice goals of reducing crime and unnecessary incarceration,” wrote Jim Bueermann, former president of the Police Foundation and Senior Fellow at the George Mason Center for Evidence-based Crime Policy. “Unfortunately, the way the grant money…is distributed no longer reflects modern policing needs and initiatives.”162

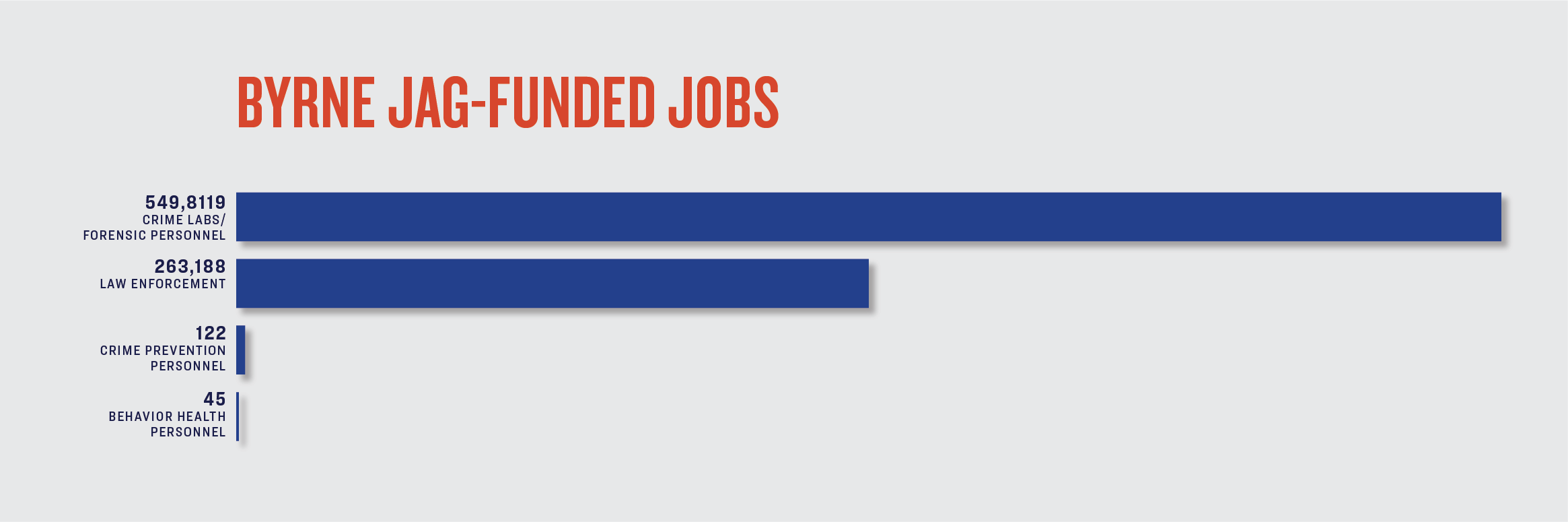

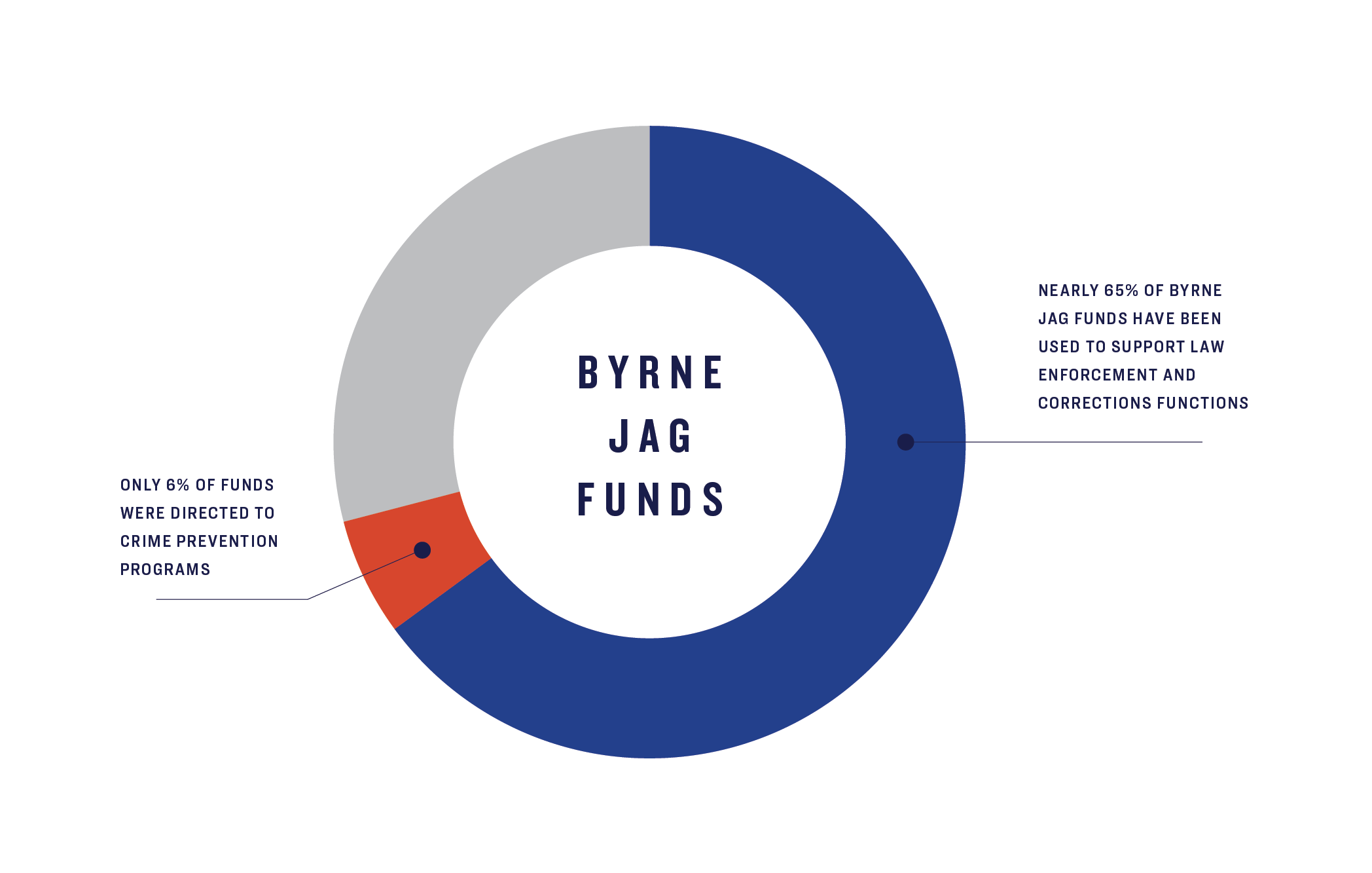

Indeed, data from the National Criminal Justice Association reveals an enormous disparity: in 2016, the most recent year for which data is available, nearly 65% of Byrne JAG funds were used to support law enforcement and corrections functions, while only 6% of funds were directed to crime prevention programs.163 A Bureau of Justice Assistance report from 2018 showed that Byrne JAG funding had been used to at least partially cover the salaries of 263,188 law enforcement and 549,8119 crime labs/forensic personnel—but only 45 behavioral health and 122 crime prevention personnel.164 An analysis by the Center for American Progress revealed that in 22 states, crime prevention efforts were completely unfunded by Byrne JAG, while in 14 states, $9 out of every $10 of Byrne JAG funding went to law enforcement functions.165

In 2010, advocates in California were able to push their SAA to allocate a far greater percentage of Byrne JAG resources to prevention-oriented and community-centric strategies such as drug treatment and reentry services, capitalizing on a large bump in funding in 2009.166 A report by the Drug Policy Alliance, which spearheaded this effort, found that this redirection of investment away from traditional law enforcement approaches would improve public safety outcomes and reduce mass incarceration, while also saving taxpayers money.

“If directed to [drug] task forces, the $115 million in 2009-10 Byrne Grants would have been likely to result in 74,500 arrests and $1.5 billion in new state costs,” the report found.167 “In contrast, based on previous analyses, the $115 million investment in treatment, probation and re-entry is expected to reduce state costs by over $330 million.”168 Indeed, in the years following this shift in policy, felony drug arrests in California declined dramatically,169 while rates of homicide dropped nearly 10% from 2010 to 2018, while increasing by the same amount nationally.170

The majority of Byrne JAG funds have not flowed to strategies backed by strong evidence. The Government Accountability Office concluded that the program’s “performance measures do not consistently exhibit key attributes of successful performance measurement systems, such as clarity, reliability, linkage, objectivity, and measurable targets.”171 In reviewing this analysis, the Justice Policy Institute found that “the impact of increased funding through these grants is unclear and benchmarks for assessment are absent. This information is consistent with past reports that showed the Byrne JAG Program did not produce significant public safety outcomes.”172

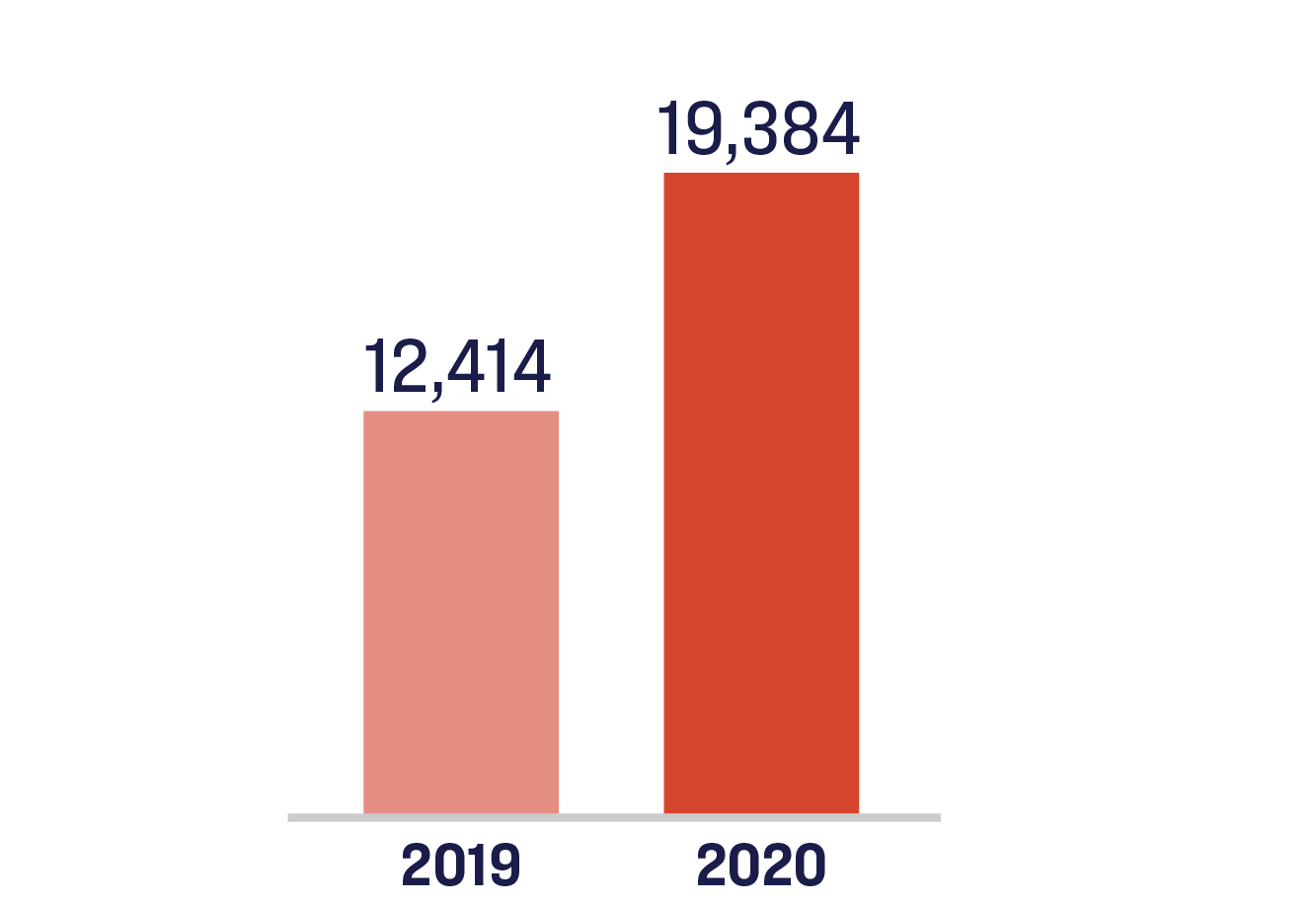

As a result, major indicators of public safety have remained essentially frozen in place for many years. When Byrne JAG was first consolidated into its current form by Congress in 2005, the US suffered 18,124 homicides.173 In 2018, that number stood at 18,830, with the overall homicide rate only slightly lower than 2005.174 While major structural reform is badly needed, advocates can help move the needle within the existing Byrne JAG framework to push investments in a more balanced and more effective direction.

Virginia Case Study

In 2019, the Educational Fund to Stop Gun Violence (EFSGV) successfully advocated for the creation of a community-specific Byrne JAG solicitation in Virginia. For Lori Haas, the senior director of advocacy at EFSGV, the experience highlights the importance of long-term relationship-building. Lori has been a leading figure in the gun violence prevention movement ever since her daughter was shot twice—thankfully surviving—in the 2007 Virginia Tech shooting.175 She started her advocacy work in Richmond the same year that now-governor Ralph Northam was entering the Virginia legislature as a freshman state senator from a rural district.

At the time, many Virginia legislators were skeptical of embracing gun safety laws and policies, fearful of upsetting gun owners. Senator Northam was different. “I walked into his office and talked to him about the need for universal background checks for gun purchases,” Lori recounted.176 “He looked at me and said, ‘That sounds like a really reasonable idea, tell me more.’ Since that moment, we’ve just had an excellent working relationship. Those long-term relationships of trust make all the difference in this work.”177

When Northam was elected governor of Virginia in 2017, EFSGV was in an excellent position to give input on gun violence prevention policy. “We’d been engaging in disproportionately impacted communities of color since 2013, when we hired our Director of African-American and Community Outreach, Kayla Hicks,” said Lori. “I talked to Governor Northam and his staff about the need to do more than pass gun safety legislation—we also emphasized the need to invest directly in community-based prevention and intervention programs.”178

EFSGV prepared a memorandum for the Department of Criminal Justice Services (DCJS), the Commonwealth’s Byrne JAG state administering agency, outlining how other states had used Byrne JAG funding to support community-based public safety strategies.179 “Everyone doing this work has to remember, state agencies are often new to some of these issues,” Lori said. “They are actively looking for input and you have to be ready to knock on the door and offer them support. That’s what we did with DCJS, and they welcomed our input.”180

On July 8, 2019, Governor Northam announced the availability of Byrne JAG funding to support community-based violence intervention programs, through a solicitation released by DCJS.181 “We know that in most communities, it is a small number of people that contribute to the vast majority of violent crime,” said Governor Northam. These grants will help provide localities with the resources to identify these at-risk individuals and get them off the path to violence.”182 After the release of this solicitation, EFSGV worked with local partners to educate them about the opportunity for additional funding.