Surging Gun Violence

Where We Are, How We Got Here, and Where We Go Next

Introduction

In many communities across the country, gun violence has been an unrelenting drumbeat. In a single deadly day, gun violence claimed the lives of a 31-year-old father in Port Allen, Louisiana; a 43-year-old in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, who was known as a stylish dresser with a great sense of humor; an 11-year-old in Columbia, Missouri, who loved to dance and play with her cousins; and a 17-year-old in Columbus, Ohio, who was a gifted boxer.

Surging Gun Violence: Executive Summary

Each day, hundreds of lives like these are lost or irrevocably changed as this crisis rages on.

But in the last two years, the tempo of this beat has gotten faster. Gun violence has skyrocketed in cities and towns across the country, leaving more devastation and more trauma in its wake.

More than 45,000 Americans were killed in acts of gun violence in 2020—a 15% increase over the previous year. This increase was primarily driven by an unprecedented 35% rise in gun homicides. In fact, more people were lost to gun violence in 2020 than any other year on record, and although final data is not yet available, the gun death total in 2021 is likely to surpass these records.

This drumbeat is ever-present, but one to which too many have become numb. For too long, this epidemic has gone unchecked, and even as it has spiraled out of control, too many leaders are choosing to do nothing. This moment demands attention, and we must do more to mitigate these increases and protect communities in crisis.

This report provides data describing how gun violence has skyrocketed in 2020 and 2021, showing that this historic rise in gun violence has primarily served to intensify this crisis in communities that already suffered the greatest burden. Additionally, this report describes and considers the factors that most likely contributed to these increases, based on available evidence, and makes suggestions for how policymakers can best respond to this unprecedented challenge.

We hope that this report can help guide a more nuanced and evidence-informed conversation about how to tackle this problem that will lead to the implementation of tangible, sustainable measures to address it.

Recent Increases in Gun Violence

Over the past two years, gun violence has dramatically increased—a phenomenon that has been well documented in the media and academic research.1 Although nearly three in five gun deaths in the US are gun suicides, this surge has been driven almost entirely by an increase in gun homicides and assaults.

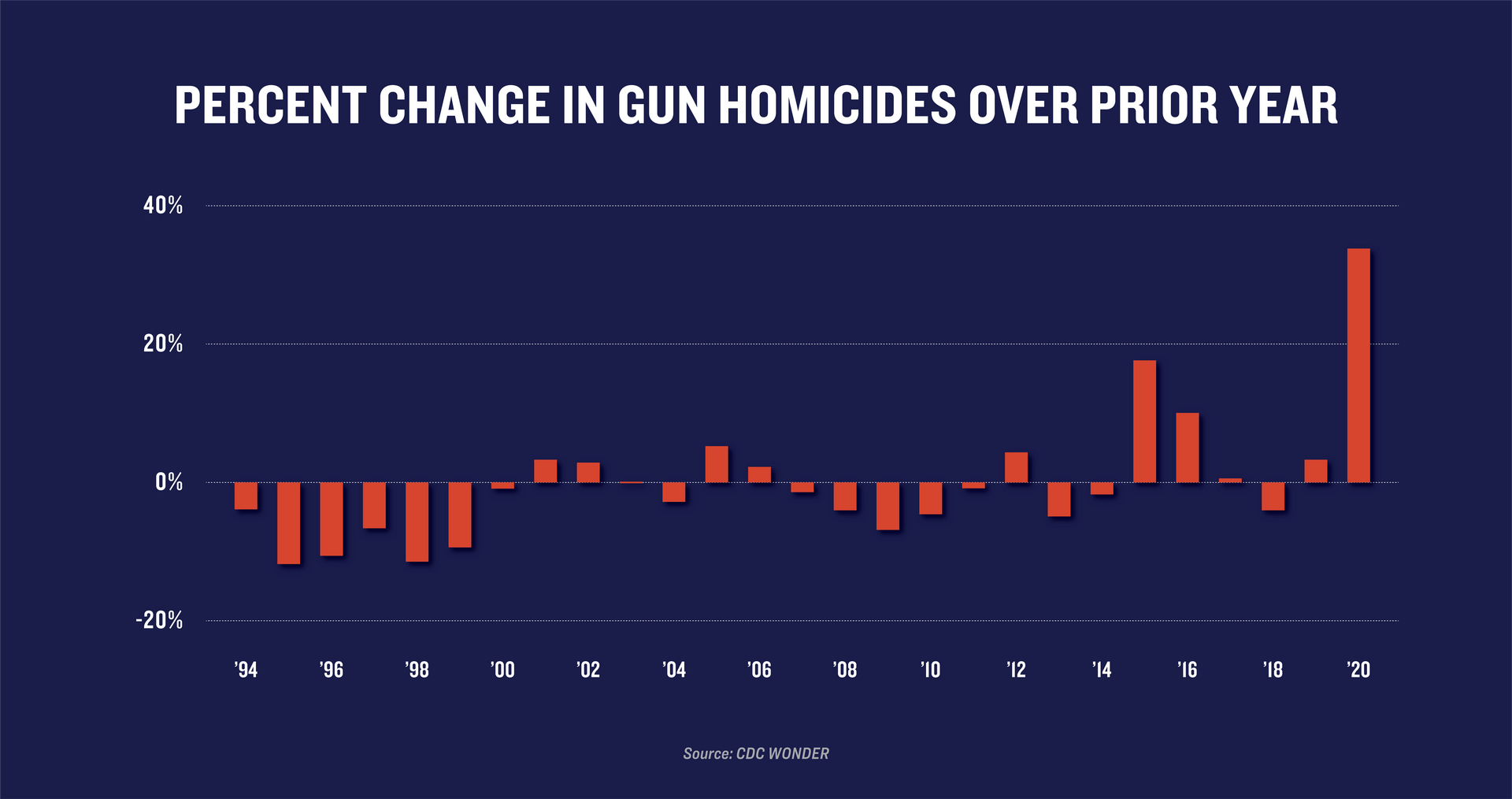

In 2020, 19,384 people were killed in gun homicides—a 35% increase in the gun homicide rate from the previous year. Both the size and the speed of this increase were unprecedented: 2020 represented the largest one-year increase in gun homicides on record. Importantly, while 2020 did not surpass the record high rates of gun homicides that the United States saw in the early 1990s, 2020 saw the highest number of gun homicides in at least four decades.

These increases, however, do not represent an entirely new trend. In fact, part of what made the increases in violence in 2020 so particularly record-breaking was that they came on the heels of several years of rising gun homicide rates. Gun homicides rose 30% from 2014 to 2019, reversing a more than two-decade trend of mostly steady decreases. Thus, 2020 did not so much create a new problem as intensify an existing pattern.

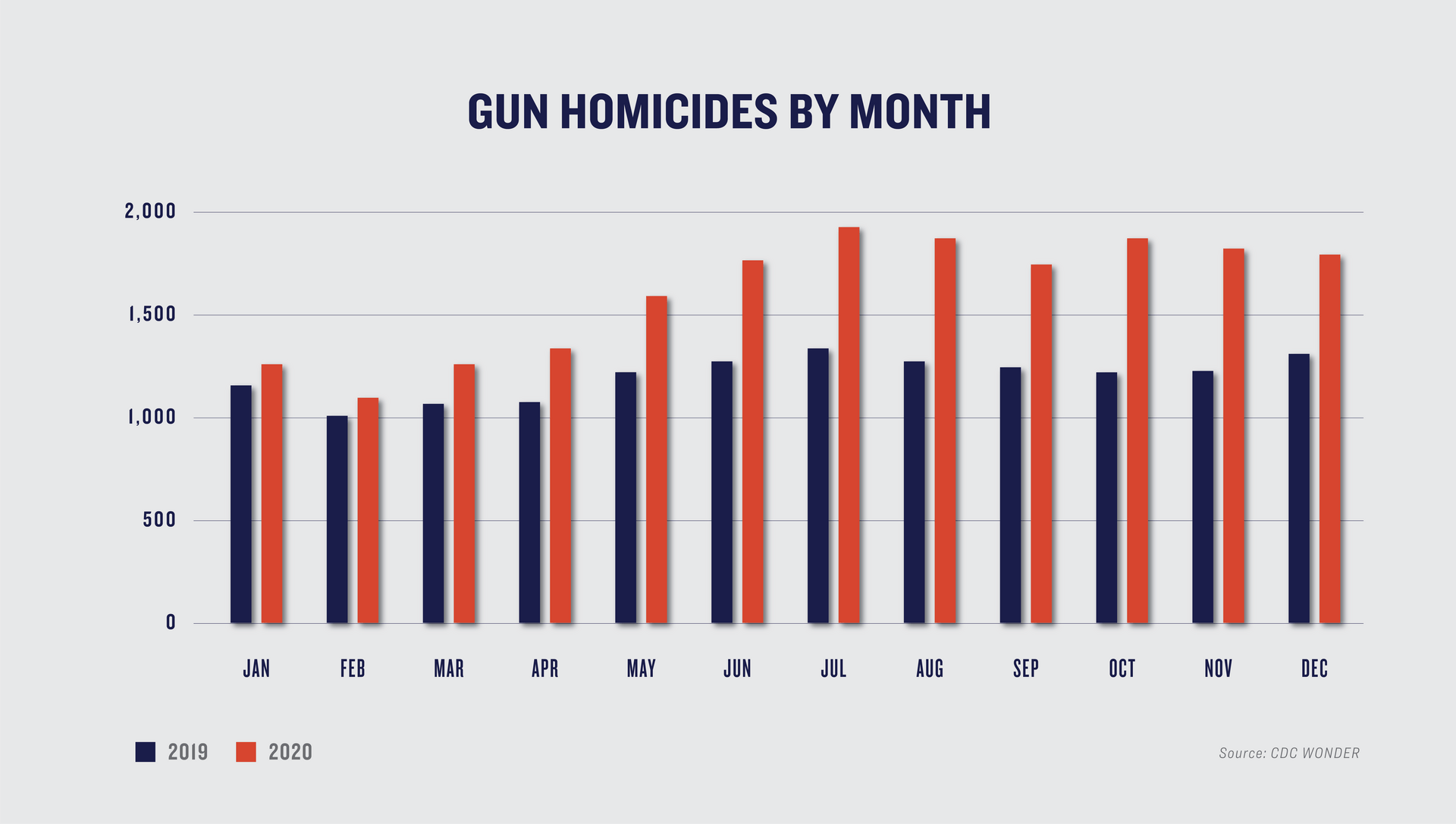

The timing of this surge in gun violence seems to vary somewhat by jurisdiction. However, nationally, there is evidence of larger increases starting in March 2020, coinciding with the declaration of the COVID-19 pandemic, with further intensification in the summer of 2020. Gun homicides in March 2020 were 18% higher than in March 2019, while in June and July 2020, gun homicides were 39% and 44% higher, respectively, than those same months in 2019. Importantly, however, monthly 2020 gun homicides were elevated over 2019 counts in every month, including January and February of 2020, suggesting that some of the factors precipitating this surge were already at work before the pandemic began.

Historically, gun homicides and shootings have disproportionately impacted American cities. One analysis found that in 2015, 53% of all gun homicides in the US took place in just 127 cities.2 Within cities, gun violence is further clustered among racially segregated, economically disadvantaged neighborhoods. For example, in Boston, 53% of the city’s gun violence occurred on less than three percent of the city’s intersections and streets.3 Given this historically disparate impact, it is unsurprising that the recent increases in gun violence have taken a particularly devastating toll on large cities.

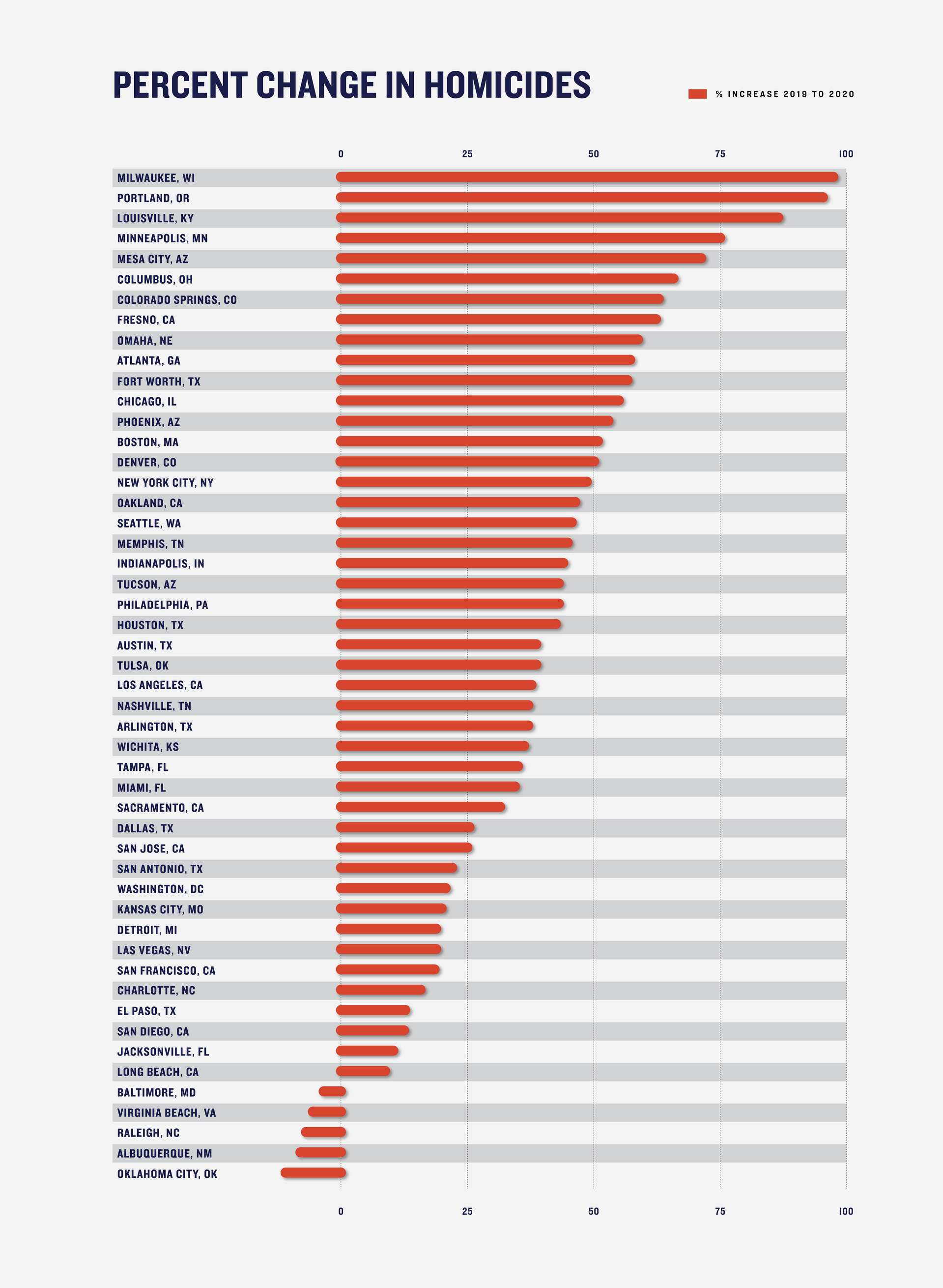

Giffords Law Center compiled police department data from the 50 largest US cities, finding that all but five of these cities saw an increase in homicides in 2020. The vast majority (88%) experienced double-digit increases. Thirty-two of these 50 cities also saw increases in 2021 over 2020 counts. Only one city, Virginia Beach, saw decreases in homicides in both 2020 and 2021.

Among these cities, total homicides increased by 26% from 2019 to 2020 and by an additional five percent from 2020 to 2021. In total, these increases led to nearly 4,300 additional homicides in these 50 cities in 2020 and 2021 compared to 2019 levels.

Many cities saw particularly sharp increases in homicides. Milwaukee, Wisconsin, saw a 93% increase in homicides in 2020 over the previous year, and eight additional cities—Portland, Oregon; Louisville, Kentucky; Minneapolis, Minnesota; Mesa, Arizona; Columbus, Ohio; Colorado Springs, Colorado; Fresno, California; and Omaha, Nebraska—saw increases in homicides of more than 60% over the prior year. In 2021, the largest increases were seen in Austin, Texas; Portland, Oregon; El Paso, Texas; and Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Available data shows that nonfatal shootings are also on the rise. In eight of the 50 largest cities that provide up-to-date nonfatal shooting data,4 the number of nonfatal shooting victims was up roughly 53% in 2020 compared to 2019, equating to more than 3,200 additional shooting victims. Nonfatal shootings in these cities increased another six percent from 2020 to 2021, resulting in another 560 excess shooting victims.

Although large cities unequally bear the burden of gun violence, it is important to note that recent surges in violence have touched smaller cities as well. In fact, FBI data shows that cities of every size type, including mid-sized and small jurisdictions, saw increased homicide rates in 2020.5 Similarly, gun homicide increases were seen in 45 of the 50 states.6 Thus, this increase is not only a big city problem but also one that has impacted a substantial number of communities across the country.

Importantly, the increases in gun violence over the years are just that: increases in gun violence, but not increases in other kinds of crime. From 2019 to 2020, property crime overall across the US fell by eight percent, as did violent crimes like rape and robbery (by 12% and 10%, respectively).7 Data from a sample of cities similarly shows that crime rates for most property and nonviolent crimes, including burglary, larceny, and drug offenses, continued to fall in 2021.8

The evidence overwhelmingly indicates that the urgent crime problem we now face is one primarily fueled by gun violence.

SPOTLIGHT

GUN VIOLENCE STATISTICS

Explore facts, figures, and original analysis compiled by our experts. To end our gun violence crisis, we need to better understand where, how, and why violence occurs.

Learn MoreCharacteristics of Surging Violence

While the level of gun violence in large cities in 2020 and 2021 was unprecedented compared to recent years, available data suggests that the underlying dynamics of gun violence were not qualitatively different compared to prior years. Increased incidents of gun violence do not appear to have resulted in the spread of violence into new communities; rather, gun violence intensified in the communities where shootings have historically concentrated.

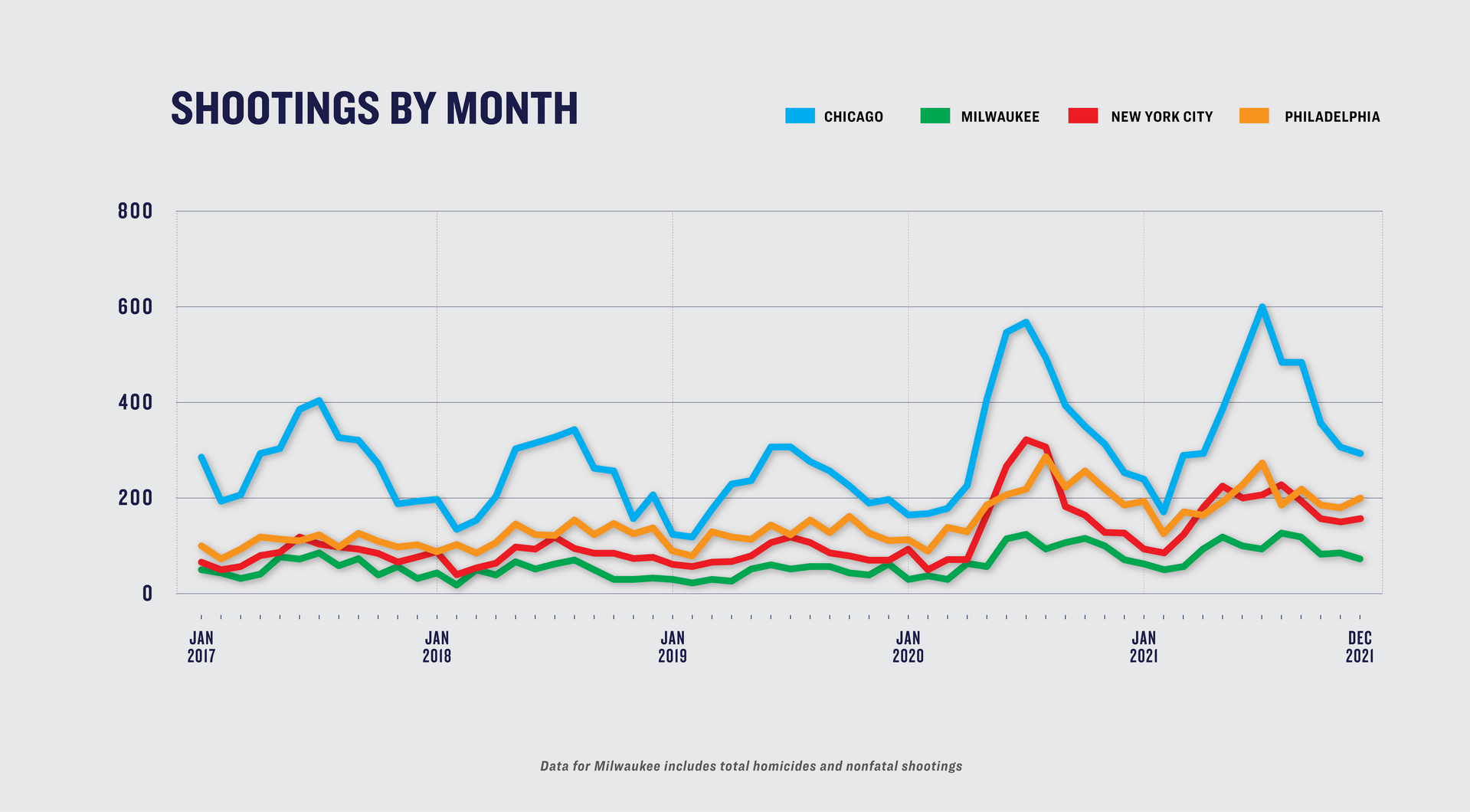

Giffords Law Center conducted original analysis of data from Chicago, New York, Milwaukee, and Philadelphia to examine how these increases changed the underlying dynamics of gun violence. These four cities are some of the only large US cities that publish timely, detailed data on the demographic and geographic characteristics of gun homicides9 and shootings that could be analyzed for 2020 and 2021.10

Chicago, New York, Milwaukee, and Philadelphia all saw increases in violence in 2020 and 2021. While the exact dynamics of these spikes varied across the four cities, each saw the most precipitous rise in shootings beginning in the summer of 2020. The biggest increase in combined fatal and nonfatal shootings from 2019 to 2020 was seen in New York (101%), followed by Milwaukee (75%), Chicago (55%), and Philadelphia (53%). Shootings continued to rise in these four cities in 2021, but at a slower rate. From 2020 to 2021, total shootings rose most in Milwaukee (13%) and Chicago (9%) and by smaller margins in Philadelphia (4%) and New York (3%).

Demographic Characteristics of Gun Violence

Historically, Black Americans have been disproportionately impacted by interpersonal firearm violence and gun homicides. In fact, across the country, Black Americans are 10 times more likely than white Americans to die by gun homicide.11

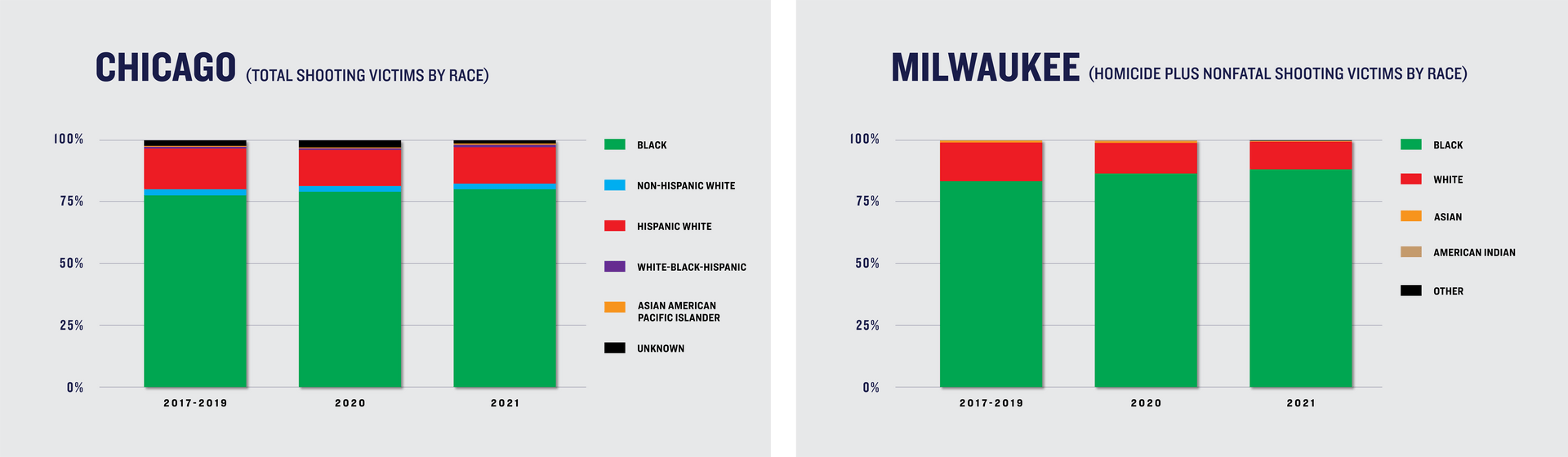

In Chicago, Milwaukee, New York, and Philadelphia, the racial breakdown of victims in 2020 and 2021 held relatively constant compared to previous years.12 Black residents accounted for the majority of victims both historically and in 2020 and 2021, comprising roughly 80% or more of combined fatal and nonfatal shooting victims in each city.

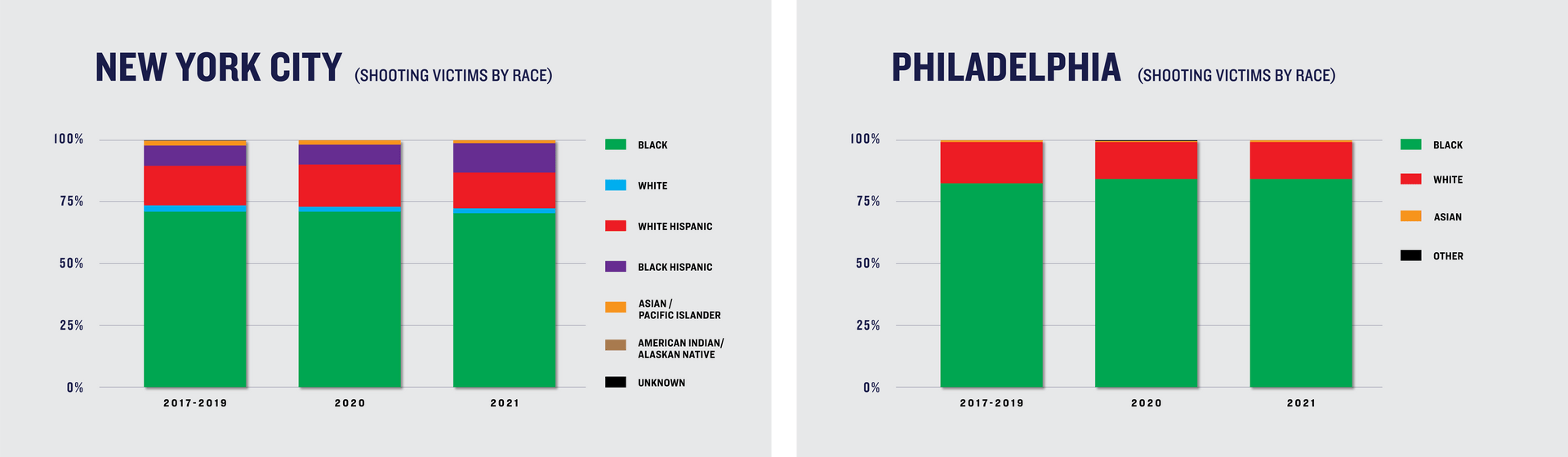

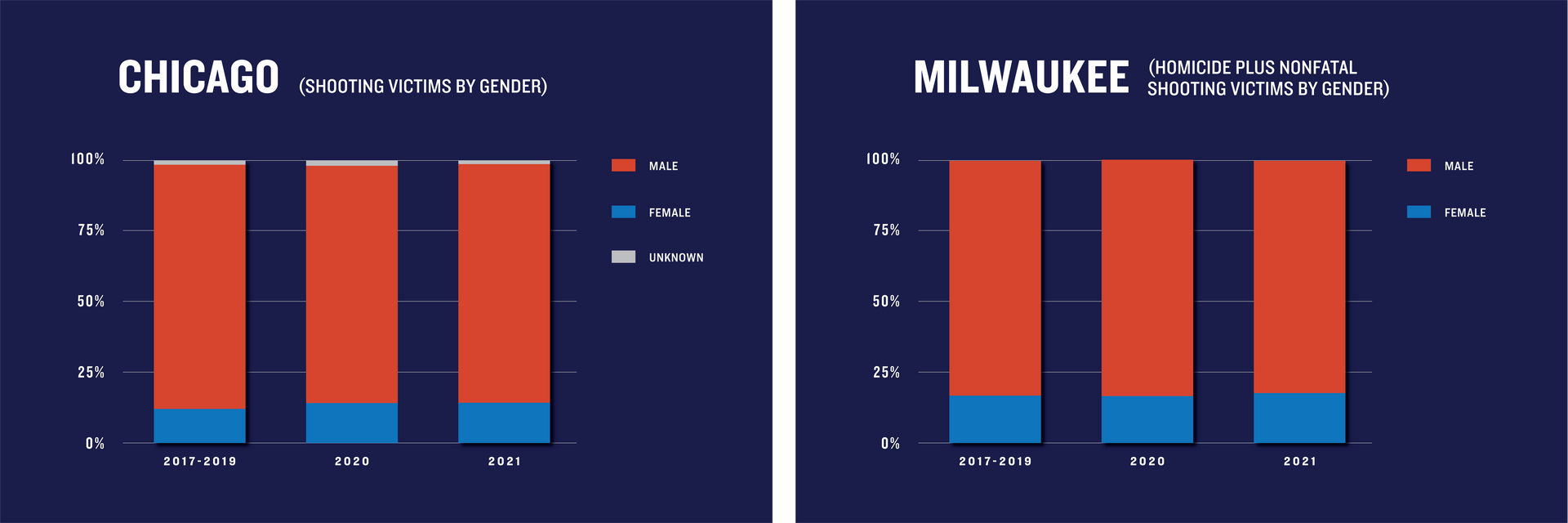

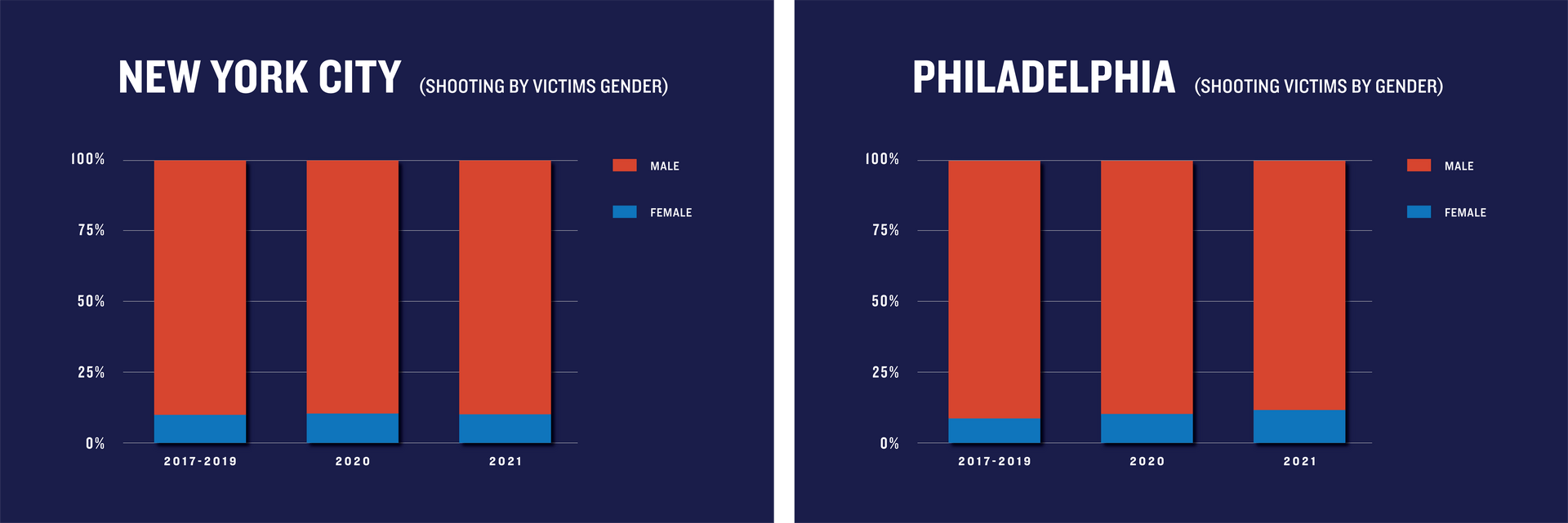

Data shows that shooting victims in 2020 and 2021 also reflected historic trends with respect to victim sex. In all four cities, the vast majority (80 to 90%) of shooting victims were male, a ratio that held consistent in both 2020 and 2021.

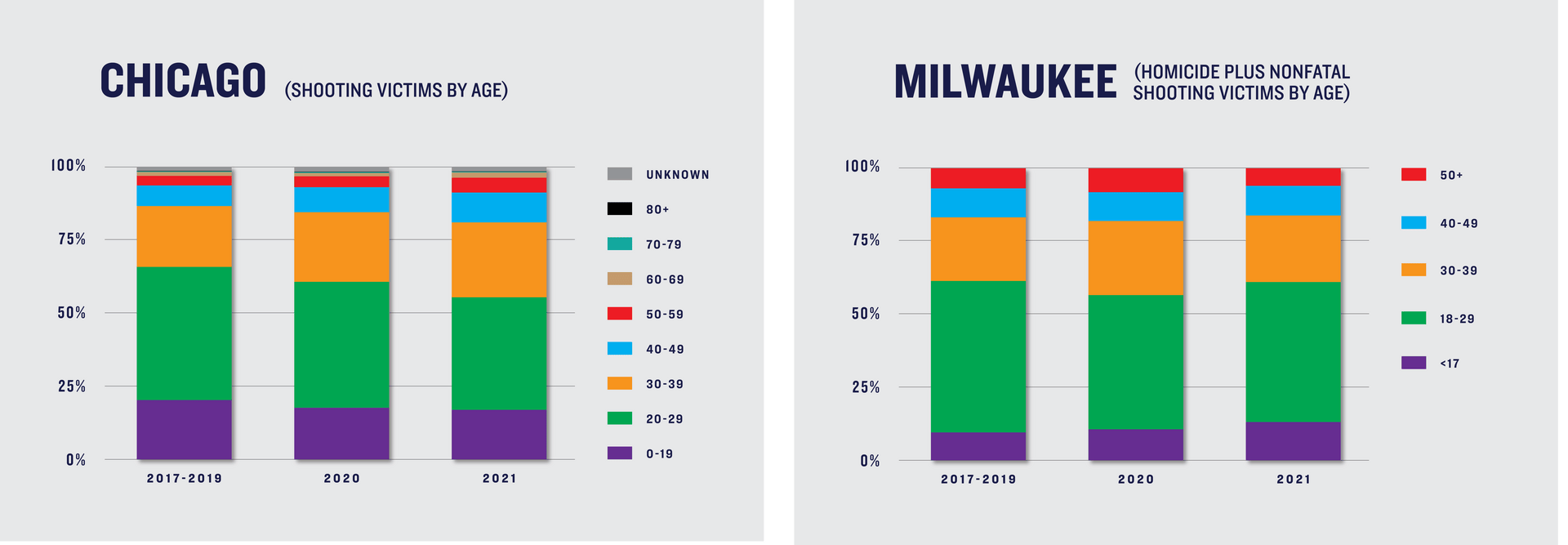

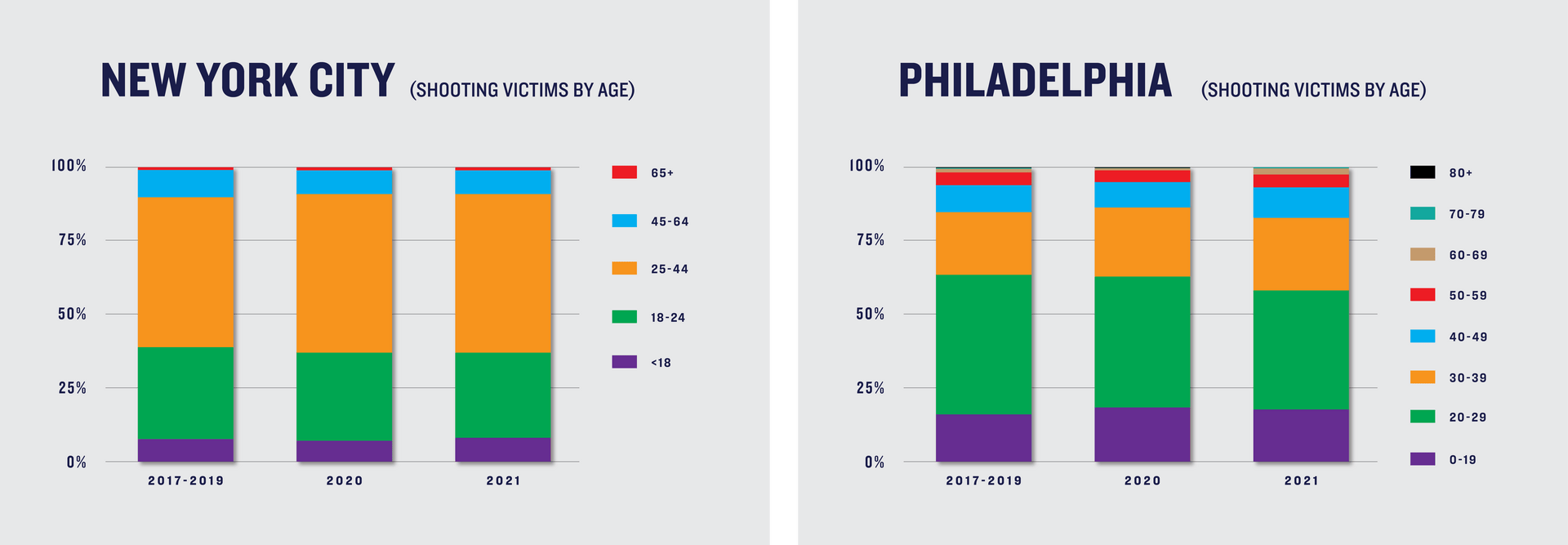

Much like the race and sex breakdown of victims, the age breakdown of victims in these four cities roughly lines up with historical trends. Each city uses different age ranges in their tracking of shooting victims, but in general, the proportional number of victims in each age range remained stable.

The ages of shooting victims appear to have remained most stable in New York. The largest observed change in New York was an increase in the number of victims ages 25 to 44, from 51% of all victims from 2017 to 2019 up to 55% and 54% of 2020 and 2021 shooting victims, respectively.

Like New York, changes in shooting victim ages in Philadelphia, Milwaukee, and Chicago suggest that victims skewed slightly older in 2020 and 2021, but still generally aligned with historical victim age breakdowns. For example, Chicago saw an increase in the proportion of victims ages 30 to 49 (28% from 2017 to 2019, 32% in 2020, and 36% in 2021), but a decrease in the proportion of victims ages 20 to 29 (46% from 2017 to 2019, 43% in 2020, and 39% in 2021).

Philadelphia saw the proportion of victims ages 30 to 39 increase from a historical average of 21% to 25% in 2021, while the proportion of victims ages 20 to 29 fell from 47% to 41% over this period. Milwaukee saw a similar trend, with increases in the proportion of victims ages 30 to 39 and a decline in the proportion of victims ages 18 to 29.

The proportion of child victims increased slightly in Milwaukee, while declining in Chicago. Specifically, in Milwaukee, nine percent of homicide and nonfatal shooting victims from 2017 to 2019 were under age 18, compared to 11% and 13% in 2020 and 2021, respectively. In Chicago, children comprised 20% of shooting victims from 2017 to 2019, 18% of victims in 2020, and 17% of victims in 2021. The proportion of child victims held roughly stable in New York and Philadelphia.

Geographic Characteristics of Gun Violence

Shootings in Chicago, Milwaukee, New York, and Philadelphia were concentrated in the same neighborhoods in 2020 and 2021 as they had been in prior years, neighborhoods which tended to be the most impoverished in each city.

In Chicago, the same 10 neighborhoods with the most fatal and nonfatal shootings between 2017 and 2019 also had the highest number of shootings in 2020 and 2021. More than half of Chicago’s shootings take place in these 10 neighborhoods, despite the fact that they contain only 15% of the city’s population. This dynamic held steady in 2017 to 2019, 2020, and 2021 (51%, 53%, and 52% of shootings, respectively). Importantly, this concentration is a reflection of how gun violence clusters in areas with high rates of disinvestment and poverty. On average, more than a third of the residents of these neighborhoods live in poverty, substantially higher than the city (22%), state (14%), and national (13%) averages.

Similarly, in Milwaukee, the neighborhoods with the most homicides remained stable from 2017 to 2021. Six of Milwaukee’s 202 neighborhoods account for just under one-third of the city’s homicides and shootings, despite only containing eight percent of the city’s population. This proportion remained unchanged over the study period: 29% of homicides and shootings occurred in these six neighborhoods from 2017 to 2019, compared to 32% in 2020 and 28% in 2021. These six neighborhoods are some of the most disadvantaged in the city, with an average of 38% of residents living below the poverty line—far exceeding the rate of Milwaukee as a whole (25%) and the national average (13%).

Data in New York and Philadelphia is grouped by police district, but similarly shows that shootings remained concentrated in a small number of police districts which serve some of the poorest neighborhoods in these cities.

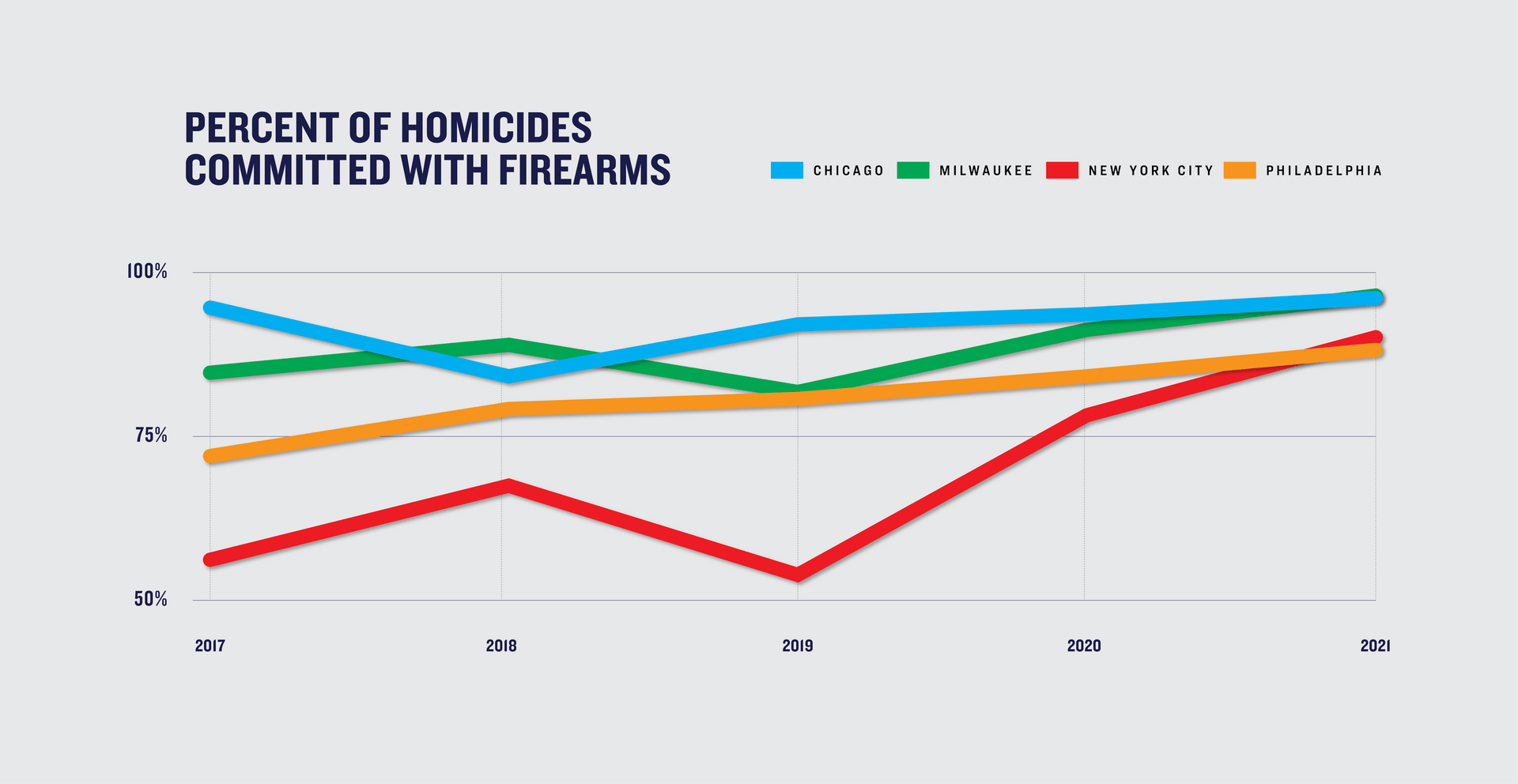

Weapons Characteristics of Violence

Nationally, guns are used in 76% of all homicides,6 with an even higher percent of homicides involving firearms often found in large cities. Analysis of data from Chicago, Milwaukee, New York, and Philadelphia suggests that guns were used in a higher percentage of 2020 and/or 2021 homicides in these four cities. This trend was most pronounced in New York. From 2017 to 2019, guns were used in 62% of homicides; guns were used in 78% of the city’s homicides in 2020 and 88% of the city’s homicides in 2021.

This same trend was seen in other analyzed cities. In Philadelphia, firearms were used in 78% of homicides from 2017 to 2019, 84% of 2020 homicides, and 87% of 2021 homicides. Shifts were seen in Milwaukee and Chicago, but at smaller total increases, likely because guns have historically been used in the overwhelming majority of homicides in these two cities. In Milwaukee, firearms were used in 84% of homicides from 2017 to 2019, 88% of 2020 homicides, and 93% of 2021 homicides. In Chicago, guns were used in 88% of homicides from 2017 to 2019, 90% of 2020 homicides, and 93% of 2021 homicides.

The fatality rates for shooting injuries in these four cities were slightly higher in 2020 and 2021, though this trend was not consistent across cities and was most pronounced in Milwaukee. In 2020 and 2021, 18% and 17% of shootings in the city were fatal, compared to just 15% between 2017 and 2019. There was some evidence of this trend in New York and Philadelphia, limited just to 2021. In both Philadelphia and New York, 21% of 2021 shootings ended in death, compared to 19% between 2017 and 2019. The fatality rate of shootings remained stable in Chicago, showing little change in 2020 or 2021 compared to historical averages.

Additional statistical analysis will be needed to fully understand the significance of these fatality rate changes; however, these data may suggest that in some cities, homicides were more likely to involve firearms and shootings were more likely to end in death in 2020 and 2021 compared to previous years.

Our analysis of data from these four cities likely suggests that across the US, even as gun violence skyrocketed, shootings did not diffuse into new communities. Rather, this problem intensified in the same communities that have historically been most impacted. Academic research has reached similar conclusions. One study that examined increases in gun violence in Chicago, Los Angeles, New York, and Philadelphia found that shootings remained concentrated in the same geographic areas and hot spots in 2020 compared to the prior four years.13

Taken together, these analyses demonstrate the deep concentration of gun violence in the nation’s poorest and most vulnerable communities—a reality that remains unchanged even after recent spikes in violence.

GET THE FACTS

Gun violence is a complex problem, and while there’s no one-size-fits-all solution, we must act. Our reports bring you the latest cutting-edge research and analysis about strategies to end our country’s gun violence crisis at every level.

Learn More

Causes of Surging Gun Violence

Identifying the causes of spikes or declines in crime is notoriously difficult, in large part because a number of factors are likely responsible for most large-scale, durable changes in crime. For example, researchers at the Brennan Center examined more than a dozen theories about what caused the crime declines that began in the mid-1990s.14 Their report concluded that a variety of social, economic, criminal justice, and environmental factors likely played some part in the decrease in crime, yet no one factor alone primarily drove this trend.15

The recent increases in gun violence are almost certainly the same, in that they are likely driven and exacerbated by multiple causes. However, because the coronavirus pandemic changed a number of factors in American life in unprecedented and to some degree unmeasurable ways, it is particularly difficult to isolate the exact combination of factors underlying the surge in gun violence. More research over the coming years is needed to help us better understand what drove the historic increase in gun homicides, but extant research and analysis of crime data can give us some insights on likely—and unlikely—culprits driving these trends.

Factors That Likely Didn’t Contribute to Historic Rises in Gun Violence

Since the spikes in violence began, efforts have been made to shift the blame on Democratic mayors and progressive policies. During one of the 2020 presidential debates, then-President Trump claimed that crime being up in Democrat-led cities was a “party issue.”16 In the summer of 2021, the Republican National Committee tweeted that crime was rising as a “direct result” of Democratic policies.17 Representative Patrick McHenry put the blame for crime increases squarely on Democratic mayors, tweeting, “Democrat-run cities across the country who cut funding for police have seen increases in crime.”18

However, data from the 50 largest cities suggests that the political affiliation of city leadership is not driving increases in violence. Among the 50 largest cities, homicides rose by an average of 39% from 2019 to 2020 in Democrat-run cities and 34% in Republican-run cities, a negligible difference.19 Academic research also suggests that historically, whether a mayor is a Democrat or Republican has no bearing on city crime rates.20

These data would suggest that it is some factor or factors beyond political party leadership—or their policy agendas—that have driven up rates of violence over the past two years. However, critics of progressive police and criminal legal system reforms continue to posit these factors as causes of these increases.

Police Reform Efforts

After the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and too many others at the hands of police, cities and states around the country embarked on long overdue efforts to rethink the role of police. In a number of cities, this led to the reallocation of some police funding to social programs or other city initiatives. Some conservative commentators and politicians have argued that this reallocation of funding, coupled with so-called “anti-police” rhetoric, has made it harder for officers to do their jobs.21

This theory, which some have dubbed the Ferguson Effect, posits that demoralized law enforcement may now feel they face a greater risk of being sued, fired, or prosecuted for doing their job—or simply do not have adequate staff to carry out their duties—and thus feel a pressure to pull back from proactive policing. However, available evidence suggests that police pulling back likely did not play a substantial role in driving the increases in violence over the past two years.

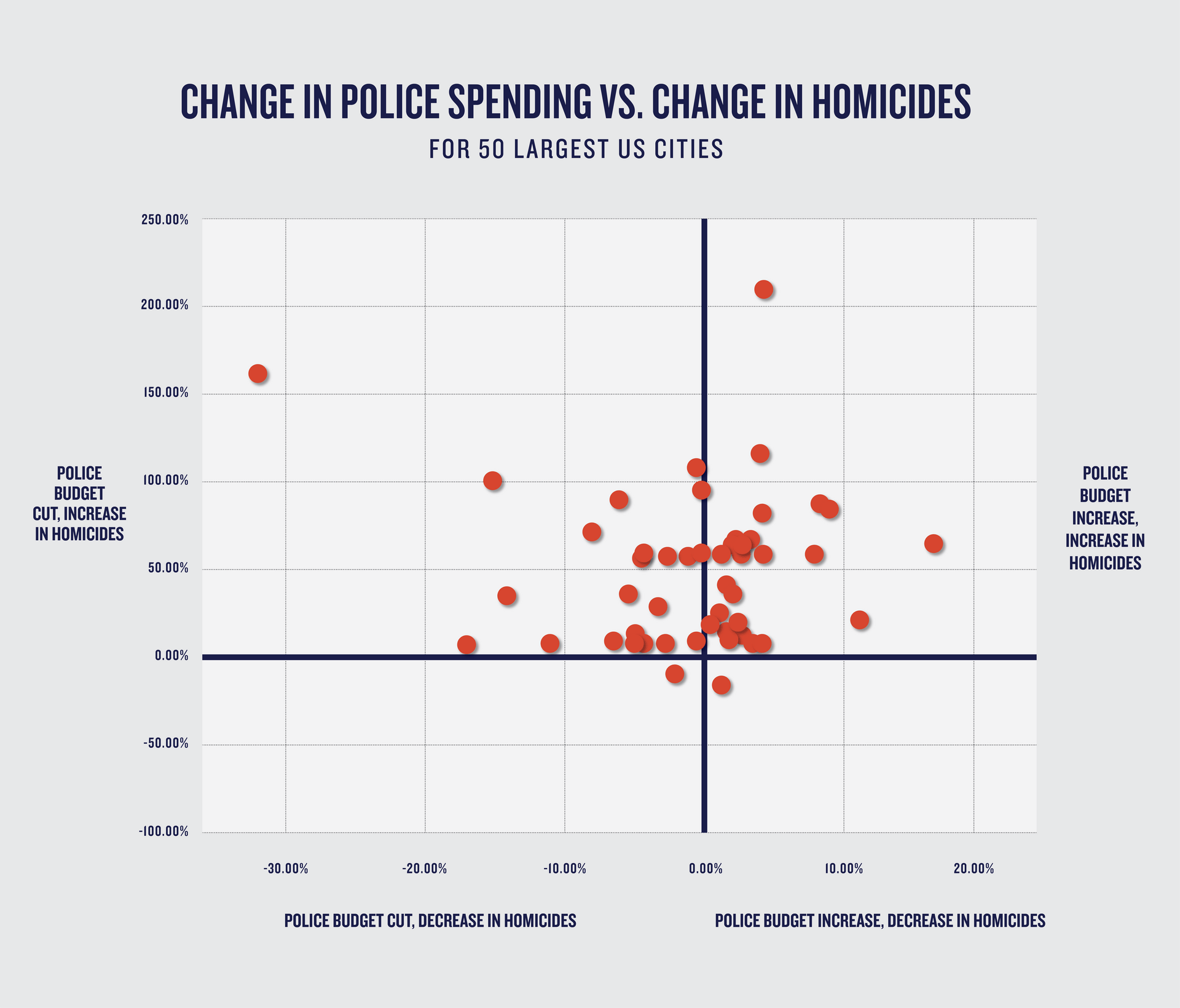

Overall, among the 50 largest cities, police department budgets were reduced by an average of 0.4% from 2020 to 2021.22 However, many large cities actually increased their police budget over this time period,23 and only four of the 50 largest cities cut their police budget by more than 10%. Importantly, among these large cities, a comparison of the percent change in police budgets from 2020 to 2021 to the percent change in total homicides shows no clear correlation.

For example, Boston, Chicago, and Portland all cut police budgets by roughly the same margins from 2020 to 2021, but each of these saw drastically different increases in homicides: eight percent in Boston, 66% in Chicago, and 210% in Portland. In a similar vein, Mesa, Arizona, and Minneapolis, Minnesota, both saw increases in homicides of 100% or more from 2019 to 2021 (118% and 100%, respectively). Minneapolis cut police spending by roughly 15%, while Mesa increased spending by nearly 4.5%. Based on this analysis, there is no evidence that cities that did and did not cut police budgets saw discernible differences in the rate of change in homicides.

Historic data also suggests that the amount of spending on police has little relation to the amount of violent crime in a given year. One analysis compared inflation-adjusted per capita spending on police from 1960 to 2018, finding no correlation between changes in spending and changes in crime rates, including violent crime rates.24 In other words, more spending in a given year was not associated with lower crime rates that year, or in the following year.15

Academic research also indicates that decreases in policing do not correspond to changes in crime or violence. Although previous scholarship has found that proactive policing can be associated with decreases in crime,25 other studies show that when police have disengaged from proactive policing for a host of reasons, increases in crime have not always followed.

For example, researchers examined data from over 2,000 municipalities between 2000 and 2018 and documented that officer deaths in the line of duty cause police to pull back from proactive policing, as evidenced by short-term declines in arrests.26 However, during these periods of pull-backs, there was no evidence of an associated increase in crime, leading the researchers to conclude that police “enforcement activity can be reduced at the margin without incurring public safety costs.”15 Another analysis concluded that there was no evidence that decreases in police activity after the murder of two NYPD officers led to either increases or decreases in crime.27

Furthermore, analyses of policing decisions show that more proactive policing does not significantly impact rates of serious crimes. One study of variation in New York City police activity driven by precinct commanders found no change in felony offenses associated with more proactive versus less proactive policing.28

Police slowdowns—a temporary labor action where officers reduce their productivity in order to advocate for changes in work policy or pay—have also been shown to have limited impacts on crime rates. One study examined a slowdown in the New York Police Department in 1997, finding that this decreased police activity had minimal effect on public safety.29 Specifically, there was some increase in minor criminal disorder offenses, including misdemeanors and violations.15 However, increases in assaults were minimal, and there was no observed increase in murders during the slowdown.15

Taken together, these studies suggest that police intentionally taking a less aggressive approach to enforcement, across a variety of circumstances, had little to no impact on crime rates. Accordingly, even if police were choosing to pull back from their responsibilities as a response to calls for police reform, evidence at present suggests that this factor alone was unlikely to have served as a major driver of increasing rates of gun violence.

Criminal Legal System Changes and Reforms

Over the last two years, some courts, jail administrators, sheriffs, and prosecutors have taken steps to prevent the spread of COVID-19 by keeping jail populations low to allow for more physical distancing. Additionally, broader criminal justice reform efforts underway in many states and cities have also led to changes in prosecution and pretrial detention policies, such as declining to prosecute petty offenses like trespassing and shoplifting, diverting more offenses to treatment rather than incarceration, and releasing more people awaiting trial without requiring bail.

While many of these changes have been heralded by criminal justice reform advocates, some elected officials and public figures have suggested that these practices may have led to the increases in violent gun crime over the past two years. Former New York Police Commissioner Dermot Shea has called the state’s bail reform “a challenge to public safety”30 and the head of the Chicago Police Union said that abolishing cash bail in Illinois was akin to “hand[ing] the keys to the criminals.”15 During a hearing with FBI director Christopher Wray, Senator Lindsey Graham posed the question of whether “one of the reasons crime is on the rise is that certain jurisdictions have basically eliminated bail.”31

JOIN THE FIGHT

Gun violence costs our nation 40,000 lives each year. We can’t sit back as politicians fail to act tragedy after tragedy. Giffords Law Center brings the fight to save lives to communities, statehouses, and courts across the country—will you stand with us?

This line of thinking suggests that not pursuing charges or not imposing bail for low-level, nonviolent offenses sends a message that people who commit crime will not face consequences. However, there is little evidence that these changes are substantially contributing to recent increases in gun violence.

The vast majority of changes resulting from progressive prosecutorial and pretrial release reforms impact those charged with misdemeanors and nonviolent felonies. For example, when New York State implemented landmark bail reforms for misdemeanor and nonviolent felony cases in January 2020, bail for almost all violent felonies—including gun possession, shootings, and homicides—was preserved.32 Similarly, pretrial releases related to COVID-19 almost exclusively involved misdemeanor and “low-level” cases.33

Given that cases impacted by these criminal legal system changes are not those involving serious offenses of gun violence, it is unsurprising that one analysis of New York City Police Department data found that from January 1, 2020 to June 30, 2020, only one of the 11,000 people released from custody pre-trial in the city was charged in any of the city’s 528 shootings over this period.34

Similarly, an analysis of a full year of data from New York State found that of the nearly 100,000 people released under the new bail reform laws that would have previously been subject to confinement or bail, less than four percent were rearrested for a violent felony while awaiting trial, and only about one percent were arrested for a firearm-involved offense.35

Importantly, by the end of 2020, in the wake of protests about the new bail reform policies, New York City judges were setting bail more often in cases where discretion was allowed, compared with earlier in the year.36 Despite an increase in the number of cases where bail was required, gun homicides and shootings continued to rise in the city in 2021.

Beyond this data from New York, the national context casts doubt about what role, if any, bail reform and progressive prosecutorial practices played in driving up rates of gun violence. The increase in homicides and gun crime was seen across the country, in jurisdictions large and small, in states and cities led by Democrats and Republicans. It is difficult to correlate more progressive prosecutorial practices and bail reform in New York, San Francisco, and Boston with increased violence across the country.

Evidence from academic research also casts doubt on this theory as a major driver of increased violence. In fact, several studies have found that leniency in prosecutorial decisions and pretrial detention for nonviolent offenders does not lead to increased crime—and may actually help reduce violent crime. Studies in Chicago37 and Philadelphia38 found that reforms reducing or eliminating cash bail for nonviolent offenses did not lead to increases in new criminal charges for those released pretrial. A study of New Mexico’s bail reform found that “while approximately one-quarter of the defendants released were arrested for a new offense during the pretrial period, very few defendants released pretrial were arrested for a new violent crime.”39

Additionally, studies in Houston,40 Miami,41 New York,42 Philadelphia,43 and Pittsburgh15 that compared similar people released and detained before trial have linked detained individuals with a higher risk of reoffending. These increases may be attributable to the criminogenic effects of carceral confinement.44 Incarcerated individuals face disruptions to their family lives and difficulties securing and maintaining employment, and they are also exposed to a network of individuals who have committed offenses. These factors, and thus incarceration and pretrial detention in and of themselves, can increase the likelihood of future offending.15

Research conducted in Suffolk County, Massachusetts, similarly suggests that declining to prosecute low-level, nonviolent offenses does not create public safety risk. In one analysis, researchers compared cases in the county, where nonviolent misdemeanor cases are randomly assigned to prosecutors who vary in their leniency with respect to deciding whether to move forward with prosecution or drop charges. People whose cases were dismissed by more lenient prosecutors were 58% less likely to be rearrested for another offense, including violent and felony offenses, in the subsequent two years.45

Researchers also evaluated the impact of a policy change related to prosecution practices, wherein the Suffolk County District Attorney specified a list of 15 nonviolent misdemeanor offenses for which there would be a presumption of non-prosecution. The likelihood of future criminal justice involvement fell for individuals who otherwise would have been charged with these offenses, with no apparent increase in local crime rates.15

A Second Chance: The Case for Gun Diversion Programs

Dec 07, 2021

Studies have also shown that diversion of first-time felony cases—another progressive prosecution practice which can allow those defendants to avoid conviction after completing a probationary period—can reduce further offending. Researchers studied people charged with a first-time felony in Harris County, Texas, and found that those whose cases were diverted were 50% less likely to reoffend.46

Collectively, these studies suggest that diversion from traditional convictions, less carceral confinement—both pre- and post-trial—and fewer prosecutions of minor offenses do not create risk for public safety and do not increase risk of violent crime. Ongoing work evaluating recently elected progressive prosecutors in 10 US districts has thus far found no evidence that prosecutor reforms have increased crime rates, including homicide rates, suggesting that these recent reforms are not substantially contributing to recent surges in gun violence.47

Factors that May Have Contributed to Surges in Gun Violence

The evidence is clear that tying recent increases to progressive policies is likely a misattribution of blame. Given that homicides increased throughout the country in most cities of every size type, we must consider more universal factors as culprits driving these increases. Specifically, the challenges and disruptions created by COVID-19, as well as a sharp decline in community confidence in police, likely created a convergence of factors that substantially increased risk for outbreaks of gun violence.

The Impact of COVID-19 on Communities and Social Services

Life in 2020 and 2021 brought unprecedented changes and challenges. COVID-19 caused substantial social and economic disruptions in communities across the country, and each of these disruptions heightened risk for compounding adversities, such as increased substance use and amplified trauma. Collectively, these factors may have contributed to increased acts of gun violence.

Throughout the pandemic, Americans have faced ongoing disruptions to daily activities in an effort to slow the spread of COVID-19. These changes meant that people were stuck at home and cut off from important social supports. In communities plagued by chronic gun violence, spending more time at home likely meant that people with unresolved disputes spent even more time in close proximity to people with whom they had conflict, who were also more likely to be stuck at home. These changes to routine activities, combined with both historic and COVID-19-related trauma, may have created more opportunities for violence to occur: people had new motivations to offend, they had easy targets, and they were cut off from capable guardians at their schools, community centers, and work.48

COVID-19 & Gun Violence: Intersecting Epidemics

—Apr 13, 2021

The pandemic also fomented a substantial and sharp increase in unemployment—from 4.4% in March 2020 to 14.7% in April 2020.49 Some research, such as a recent analysis of 16 cities, suggests that unemployment may have played a role in driving increases in firearm violence and homicide.50

Historical research has shown that unemployment creates individual risk for violence,51 but there is mixed evidence as to whether changes in unemployment create population-level risk for increased violence.52 Importantly, previous changes in unemployment have been less sharp than those induced by the pandemic. Because research is clear that gun violence concentrates in socioeconomically disadvantaged areas,53 it is possible that the acute worsening of these conditions during the pandemic further exacerbated this risk.

Additionally, both the pandemic and rising unemployment created trauma and strains such as anxiety, depression, and hopelessness. These negative experiences may have made people more susceptible to using violence to address conflicts.54 As one example, survey data suggests that there were significant increases in alcohol consumption during the pandemic, likely as a means to cope with these new strains.55 A substantial body of research shows that acute and chronic alcohol misuse increases the likelihood of risky behaviors involving firearms, including the risk for perpetrating both interpersonal and self-directed firearm violence.56

Finally, it is important to remember that unaddressed trauma is a driving factor of gun violence.57 Unfortunately, the pandemic amplified factors like trauma and grief: many communities hit hardest by gun violence were those that have suffered the highest burden of COVID-19 cases and deaths.58 These traumas and toxic stresses—which many communities have endured for generations—adversely impact brain development, decision-making capacity, and impulse control, and can cause people to become hypervigilant, interpreting even safe situations as dangerous.59 Unfortunately, the increases in gun violence over this period simultaneously added to the trauma burden, most acutely in communities with historically high rates of violence. While more research is needed to understand the part that pandemic-related trauma played in perpetuating gun violence, the role that trauma plays in promulgating violence must be acknowledged as a potential culprit.

Social Unrest Related to National Reckoning Around Policing

Every year, more than a thousand people die at the hands of American law enforcement officers.60 While the vast majority of these incidents have historically received little public attention beyond the local level,61 the murder of George Floyd was different, setting off a cascade of events that likely contributed to the explosion of violence in the summer of 2020.

The viral footage of George Floyd’s death reinvigorated debate about racial biases in policing and sparked peaceful protests in cities across the country. Data aggregated from Twitter shows that in the 10 days after George Floyd was murdered, videos related to racial justice and the Black Lives Matter movement were watched over 1.4 billion times, with these topics accounting for 90% of the top 100 watched videos on the platform.62 During roughly the same period, polling data shows sharp decreases in the percent of Americans viewing police favorably and reporting trust in police.63 A Gallup poll conducted over the summer of 2020 found that just 19% of Black Americans had confidence in police.64

As Giffords Law Center described in a recent report on police-community trust, when people lose trust and confidence in police to keep them safe and treat them fairly, cycles of violence can be perpetuated. When a community’s trust in police is low, individuals may be concerned about calling law enforcement to solve disputes, fearing that doing so could put their safety or the safety of others in their community at risk. In turn, this can increase the likelihood that people involved in disputes will turn to retaliatory violence to solve problems, fueling more violence and perpetuating a vicious cycle.

The consequences of a lack of police-community trust were documented after the 2004 death of Frank Jude, who was beaten by officers at a party in Milwaukee. After news of Jude’s beating broke in February 2005 and caused substantial public outrage, there was a sharp drop in 911 calls reporting crimes to the Milwaukee police, driven largely by decreases in crime reporting in Black neighborhoods.65 Overall, residents placed an estimated 22,200 fewer 911 calls reporting crimes to the police over the course of the following year.15 As 911 calls fell, violence spiked, with a 32% increase in homicides in Milwaukee from March to August 2005.15

Similarly, some scholars have postulated that the increases in gun homicides in 2015 and 2016 may have been attributable to a decrease in police-community trust after the high-profile 2014 police killings of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, and Eric Garner in Staten Island, New York. One 2019 study suggests that the erosion of trust in police after these incidents may have played a role in increasing both Black and white homicide rates in 2015 and 2016.66

Source

Mapping Police Violence, “National Trends,” last accessed July 27, 2023, https://mappingpoliceviolence.squarespace.com.

Early evidence suggests that the murder of George Floyd may have similarly caused communities to lose confidence that police would keep them safe and treat them fairly, leading people to find other ways to solve disputes in their communities. One analysis of data from eight cities found evidence that citizen crime reporting fell sharply after George Floyd’s death.67 In the week before George Floyd’s death, there were approximately 207 911 calls made per gunshot incident recorded by ShotSpotter, a gunshot detection system.15 In the week after his death, less than 90 911 calls were made per recorded gunshot.15 Depressed call rates persisted throughout the rest of 2020 and were not shown to increase even after the April 2021 murder conviction of one of the officers responsible for George Floyd’s death.15

A lack of trust in police can also be reflected in low clearance rates for serious crimes. Studies demonstrate that homicide cases are much more likely to be solved when witnesses and residents provide information to the police.68 However, a fear of or lack of trust in police can make this kind of information sharing less likely and leave high numbers of unsolved homicide and shooting cases in communities.69

According to FBI data, only 54% of all US homicides in 2020 were cleared by police, a seven percent drop from the homicide clearance rate in 2019.70 Accordingly, police did not make an arrest for nearly half of all homicides committed in 2020. In large cities where violence concentrates, these percentages can be even more drastic. For example, in 2020, Philadelphia cleared only 37% of homicides and 19% of nonfatal shootings, meaning that no arrest was made in nearly 1,800 homicides and nonfatal shooting cases that year.71 These figures represent a substantial drop in the already low clearance rates in the city: 41% for homicides and 27% for nonfatal shootings in 2015.15

While multiple factors may have impeded law enforcement’s ability to clear cases over the last two years, it is likely that the severe fractures in police-community trust and the reduced reporting of crimes to police created additional hindrance to law enforcement’s ability to identify perpetrators of acts of serious gun violence. Low clearance rates can further erode public confidence in police,72 creating a cycle that has likely sustained increased levels of violence over the past two years.

Surge in Gun Sales

Amidst the increases in gun violence over the past two years, there have been record-breaking firearm sales and some evidence that more Americans are choosing to bring firearms into their homes. While more research is needed to better understand the intersection of the rises in violence and the rises in gun purchases during the pandemic, previous research has found that increases in gun purchasing have been associated with increased gun violence.

At the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, gun sales substantially increased, likely because the pandemic induced new uncertainties about safety and created concerns about social disorder. Similar fears after the May 2020 murder of George Floyd may have driven increased purchases during the summer months. Overall, Americans purchased an estimated 22 million guns in 2020—an increase of nearly 65% over the previous year’s sales.73

Gun sales remained higher than average in 2021. In fact, since the National Instant Check System (NICS) became operational in 1998, the nine weeks with the most background checks processed through this system occurred during 2020 or 2021.74 Eight of the 10 days with the most background checks processed happened during these same two years.15

Researchers suggest that nearly three million more US adults purchased firearms in 2020 than in 2019, and 3.8 million Americans became new gun owners after a firearm purchase in 2020.75 These increased purchases and the increase in new gun owners in 2020 led to an estimated 9.3 million people becoming newly exposed to household firearms, including three million children.15 These data suggest that not only were there more guns sold, but that an expanded group of people had access to guns after 2020. Importantly, gun access itself has been associated with a higher risk of experiencing gun violence.76

Previous surges in gun purchasing, often in response to mass shootings or presidential elections, have been found to lead to increases in gun violence.77 However, the role of new firearm purchases in the recent increases in violence has not been as clearly demonstrated. One study found that through May 2020, states with higher levels of excess firearm purchases had larger increases in gun violence.78 Analysis over a longer period shows less durability in this trend. A study analyzing data through July 2020 was unable to detect this trend for firearm violence overall, though there was still evidence that increased firearm purchases were associated with increases in intimate partner violence.79

In contrast, other data points suggest that the unparalleled increase in civilian gun ownership may have played a role in promulgating gun violence. One analysis of data from the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) suggests that in 2020, newly purchased guns were more likely to be recovered at crime scenes than is typical.80 In fact, in 2020, police recovered almost twice as many guns purchased in the last year than they did in 2019.15 Historically, guns that are recovered in connection with crime shortly after purchase—often referred to as a gun with a short “time-to-crime”—are more likely to have been acquired for criminal purposes or to have been trafficked in the illegal market.81

There are other indications that the rise in gun purchasing may have coincided with an increase in public gun carrying—which can create opportunities to escalate conflicts more easily and increase risk of violence. One analysis found that gun carrying was 108% higher in Chicago in 2020 compared to 2019.82 In fact, even as Chicago police officers made fewer stops during the pandemic, more guns were recovered: police stops decreased nearly 70% between January and May 2020, but officers actually found 83% more firearms in May than in January.15

The researcher explained that “unless the police have become dramatically better at figuring out who is illegally carrying a gun…the implication is that lots more people are carrying guns illegally in Chicago.”15 Another analysis of data from 10 cities similarly suggests that there were more people carrying guns in 2020, as evidenced by the fact that the share of arrests where people had weapons increased as the pandemic began.83

SPOTLIGHT

GUN LAW SCORECARD

Every year, the data is clear: States with strong gun laws have less gun violence. See how your state compares in our annual ranking.

Read MoreRecommendations

In too many cities, gun violence has reached unacceptably high levels. And unfortunately, violence often impacts communities in cyclical patterns: one shooting in a community can set off a cascade that makes another shooting more likely to occur. Accordingly, even if some of the factors driving these increases abate, gun violence may not necessarily drop simultaneously. These increases in gun violence in recent years have lit the flames for retaliatory violence and have deeply traumatized communities and the people living in them.

We cannot just expect these communities to return to “normal” on their own. Instead, we must implement solutions that can help reduce gun violence now while also building an infrastructure to help cities prevent future spikes in violence. These solutions must be responsive to the realities of gun violence’s impact on economically disadvantaged communities of color, and they must be made with consideration of the factors that most likely led to increased gun violence.

Invest in Community Violence Intervention Programs

Because gun violence has primarily intensified in the communities which have historically been plagued by unacceptably high rates of gun violence, our response to this crisis must be centered around these communities. Over the past several years, communities have developed promising strategies to prevent and intervene in concentrated cycles of violence have been developed. These strategies, often referred to as community violence intervention (CVI) programs, are rooted in a public health approach.

In many communities, gun violence spreads much like a communicable disease. Numerous studies demonstrate that a person who is exposed to gun violence is significantly more likely to commit violence themselves,84 and one analysis found that young people who are part of a social network where someone else has experienced violence are 900% more likely to themselves be a victim of gun violence.85 Given these underlying dynamics, CVI programs rooted in a public health approach can be uniquely responsive to the particular cycles of violence plaguing our nation right now.

CVI programs engage individuals at highest risk of being victims or perpetrators—or both—of violence. These programs utilize a variety of strategies to reach out to the small number of people responsible for promulgating the vast majority of gun violence in their communities, build relationships and provide supportive social services, address conflict through nonviolent means like de-escalation and mediation, and work to support community healing from violence.

Studies have shown these programs to be remarkably effective, resulting in both relatively quick and sustained reductions in serious gun violence. For example, one CVI program implemented in a South Bronx, New York, site was found to result in significant declines in gun injuries (37%) and shooting victimizations (63%) over a three-year period, compared to a matched neighborhood.86 Studies of a CVI program in Sacramento, California, have found that the program was associated with city-wide reductions in gun violence from both 2014 to 2018 (14%) and 2018 to 2019 (18%), with benefits also observed among participants engaged in the program, such as a significant decline in the risk of being arrested or charged for a gun crime.87

In the midst of unprecedented surges in gun violence, communities need and deserve substantial investment in these immediate and locally driven interventions. It is crucial that communities have funding to scale existing CVI programs to meet new demand, and that cities and communities across the country that don’t yet have these programs obtain the funding to implement them.

For far too long, these programs have been underfunded by federal, state, and local governments. Fortunately, President Biden has publicly committed to investing $5 billion in community violence intervention programs, with efforts to scale up to that number in his Fiscal Year 2023 budget request where he requested $500 million for CVI initiatives in the Department of Justice and CDC, as well as continued efforts to secure $5 billion through social impact focused legislation.

State funding also plays a role in helping to implement and scale CVI work. In 2021, for example, California passed legislation dedicating $200 million in funding for the California Violence Intervention and Prevention Grant Program (CalVIP), which funds CVI work in communities across the state. More states need to follow this example and appropriate specific funding for these lifesaving programs.

It is important to note that more funding for this work is needed not just to expand these programs to more cities and neighborhoods, but also to ensure that existing programs are fairly and sustainably supported. CVI work is demanding, emotionally draining, and often dangerous. In a recent report, Giffords Law Center surveyed nearly 200 CVI outreach workers and made recommendations about how more funding should be used to better support the people who do this lifesaving work. The success of this field depends on providing adequate pay, benefits, and training to these workers who put their lives on the line each and every day to make our communities safer. New investments in this work must bear this reality in mind to ensure that this work can be sustained long after it is implemented.

Implement Reforms to Promote Trust in Police

As described above, the research is clear that when police-community trust is low, there is greater risk of gun violence. Thus, to address recent increases in gun violence, it is essential that we take steps to repair this trust, rather than lean back on a broken, overly onerous system which unfairly discriminates against people of color.

Police departments and community leaders across the country have demonstrated that reformed policing practices can help build community trust and confidence in law enforcement, promote active community cooperation in promoting public safety, and disrupt cycles of violence. Policies that promote officer accountability, encourage de-escalation of high risk incidents, and prohibit the use of excessive and unnecessary force provide important guardrails against police brutality and promote community dignity and respect.

TAKE ACTION

The gun safety movement is on the march: Americans from different background are united in standing up for safer schools and communities. Join us to make your voice heard and power our next wave of victories.

GET INVOLVED

Numerous studies have found that these reforms help to significantly reduce civilian deaths at the hands of police. For example, a study of 91 large police departments found reforms of use-of-force policies—such as requiring the exhaustion of other means prior to shooting, bans on chokeholds and strangleholds, and restrictions on police shooting at moving vehicles—led to reductions in the number of people killed by police.88

Additionally, studies of procedural justice trainings, which teach officers to do their work with fairness, equity, transparency, and concern for the community, show that such programs can reduce both civilian complaints against police and use of force by police officers against civilians.89 Another study demonstrated that training police in de-escalation practices resulted in decreases in use of force incidents, citizen injuries, and officer injuries by 28%, 26%, and 36%, respectively.90

These studies suggest that concerted, evidence-based reforms to policing in America can help prevent police violence, potentially averting incidents that incite the largest fractures in police legitimacy and are most likely to exacerbate cycles of retaliatory violence. Additionally, reforms which refocus police efforts on solving a community’s most serious gun crimes, instead of prioritizing low-level offenses, can help rebuild community confidence in law enforcement’s responsiveness to their needs and ability to keep them safe.72

Importantly, community models also demonstrate the beneficial impacts of police reform efforts—and suggest that such reforms can guard against surges in gun violence. For example, police reforms in Camden, New Jersey, led to durable transformational progress. While many cities across the country saw increases in gun violence over the past two years, available data suggests that gun homicides dropped over this same period in Camden.

When Police Break Trust, Violence Spikes

Jun 26, 2020

Camden’s story was detailed in a recent Giffords Law Center report as well as a 2015 Task Force on 21st Century Policing report,91 showing how progress was made in a short period of time. In 2013, in the midst of exorbitantly high levels of violence and budget cuts, Camden disbanded and reconstituted its police department as a new county police force.92 The new Camden County Police Department undertook a concerted effort to infuse community policing and trust-building efforts throughout all of its officers’ work.15

This new department, under the leadership of Chief J. Scott Thompson, directed officers to proactively change the community’s perceptions of the police force and engage in community policing. Officers began new foot patrols and proactively introduced themselves to community members before there was any crime or crisis.93 Officers were also trained to de-prioritize lower level offenses, such as traffic violations, and respond to these offenses with warnings instead of tickets that carry hefty fines.15

Camden also re-examined its policies and culture around use of force. New programs were instituted for officers to receive training around de-escalating conflict; one study found that this new training resulted in a 40% decrease in serious use-of-force incidents across the department.94 The department also adopted a new use-of-force policy with the help of The Policing Project at New York University. This 18-page policy encourages police to incorporate harm reduction strategies in their work and clearly defines when force is reasonable and when it is not.95 Importantly, the policy clearly defines that officers who violate the policy “will be” disciplined—not just “could be” disciplined—and requires officers to report violations of this policy.15

Camden’s reforms have been both astounding and lifesaving. In the two years after the city implemented these reforms, violent crime in Camden fell by 24% and homicides were cut nearly in half.96 In fact, the number of homicides in Camden fell by two-thirds between 2012 and 2018, down to a three-decade low, even as many other cities across the country experienced large spikes in violence.15 Excessive force complaints against police have fallen by 95% since 2014.97

Source

“National Trends,” <i> Mapping Police Violence<i>, last accessed, May 1, 2024, https://mappingpoliceviolence.squarespace.com/nationaltrends.

Perhaps even more encouragingly, however, there is no evidence that the nationwide spike in gun violence that coincided with the pandemic reversed Camden’s progress. Perhaps Camden’s success is most apparent when compared to its neighbor just across the Delaware River: as gun homicides soared by more than 46% in Philadelphia from 2019 to 2020 and then another 18% from 2020 to 2021,98 Camden saw a six percent decrease in gun homicides in 2020 followed by another six percent decrease in 2021.96 Additionally, shootings in Camden remained well below historical averages over this period.15

Camden’s story is not without struggle, nor without important, persistent efforts from community members advocating for change. But these results show substantial promise and suggest a model for more cities to follow. Police reform efforts must be a part of any plan to comprehensively reduce gun violence, and without these reforms, we risk additional fractures in police-community trust that could lead to future surges in violence.

Strengthen Gun Safety Laws

Strong gun safety laws are an essential foundation to any plan to prevent gun violence. Unfortunately, however, our federal gun laws and the laws of most states leave too many loopholes that make it too easy for guns to fall into the hands of those who cause harm. In fact, on Giffords Law Center’s Annual Gun Law Scorecard, 24 states received an F—meaning that nearly half of all states lack even the most basic of gun safety laws critical to keeping communities safe.

Weak gun laws fuel gun violence through two important channels. First, weak gun laws permit the illegal acquisition of guns by people prohibited by law from having them. And second, weak gun laws facilitate the flow of illegal guns to people involved in high-risk networks—a key mechanism in shaping rates of deadly violence in American cities and across the country. While the exact role our nation’s lax gun laws played in fueling increased violence in recent years is unclear, strengthening our gun laws must be part of our response to this crisis.

Studies largely show that states with stronger gun laws have lower homicide rates.99 For example, one study assigned point values to states for having certain gun safety policies, finding that states with the highest gun law strength scores had a 40% lower firearm homicide rate compared to states with the lowest scores.100 Evidence also suggests, however, that these impacts may be dependent on the policies of surrounding states: states with weak laws that neighbor states with strong gun laws can see reductions in gun homicides,101 while states with strong gun laws that neighbor states with weak gun laws can see increases in gun homicides.102 Therefore, this response requires both a strengthening of state laws and a strong federal response to help ameliorate the current patchwork of variant state laws.

Research is also clear that better regulation of the legal gun market can help reduce the role of the illegal market in fueling cycles of community violence.103 For example, one study of Boston crime gun recoveries over seven years found that only one of the 837 firearm recoveries from gang-involved individuals104 was a recovery of a firearm from the original purchaser.105 In fact, guns recovered from gang-involved individuals in the city were more likely to have been originally sold in states with far weaker gun laws than those in place in Massachusetts—such as New Hampshire, Maine, and Southern states along I-95—compared to guns used by possessors not considered gang-involved.15

The recent rises in violence have clearly shown that our current gun laws are not adequately protecting communities from surging violence. Laws that reduce easy access to firearms for people at risk of violence—including universal background checks and firearm licensing laws—are a critical foundation to prevent gun homicides and other types of gun violence. But unfortunately, these laws have not been passed and implemented in too many communities, even as this crisis intensifies. It has never been more urgent that federal, state, and local legislators enact gun safety laws to help promote and sustain reductions in gun homicides.

Improve Gun Violence Data Collection

Tackling any public health crisis requires accurate, timely data about the scope and causes of the problem to be addressed. For example, during the coronavirus pandemic, state and federal agencies implemented robust systems to monitor COVID-19 cases and deaths. Although this data was not perfect, it was critical for making real-time decisions about how to respond. Policymakers used this data to make decisions about whether to require masks, limit indoor gatherings, close schools, and allocate funding for resources. Hospitals and public health workers used this data to assess future staffing and supply needs. Even members of the public relied on this data to make informed decisions about their own potential for risk.

Simply put, this real-time data was crucial to nearly every effort to address this public health crisis. But when it comes to surges in gun violence, we are operating without similar data. In fact, if we monitored COVID-19 deaths the way we do gun deaths, we would have to wait until December of 2022 to find out how many people died from COVID-19 in 2021.

Data on gun homicides in the United States is collected by both the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the FBI.106 The CDC’s gun death data is collected from death certificates and is considered to be nationally comprehensive. However, the CDC’s publicly available gun homicide data is broken down only by state and county, limiting its use for city-level analysis. Additionally, this data is released with an approximately one-year lag, meaning that complete and final data for a calendar year is not available until December of the following year.107

The FBI also collects data on gun murders. This data is based on information voluntarily submitted by police departments, and not all agencies participate or submit complete information each year. However, city-level data is available for participating agencies. This data is also released with a lag, with complete data for a calendar year published in September of the following year.108

In 2021, the FBI transitioned to a new system for collecting crime data, including data on murders, known as the National Incident Based Reporting System (NIBRS). On the surface, NIBRS data is more nuanced and detailed than the previous reporting system, providing additional information about victim characteristics and crime circumstances. However, early data suggests that many departments, including many of the nation’s largest police departments—such as New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago—have not made the transition to this new system and have not been submitting crime counts to the system thus far.109 Alarmingly, many large police departments will likely submit no data to the FBI for 2021, severely compromising the accuracy and utility of national crime data.

While there are extreme limitations to the timeliness and completeness of data on gun homicides, national collection of data on nonfatal shootings is even more inadequate. Historically, no data on nonfatal shootings has been collected by the FBI. Estimates of nonfatal firearm injuries are released based on extrapolation from a sample of hospitals through the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP).110 However, as of the publication of this report, this data is only available through 2019. Additionally, some researchers have expressed concerns about the quality of demographic and intent-level breakdowns of this data.111

We cannot hope to truly address surges in gun violence unless gun deaths and injuries are monitored with sufficient detail and in closer to real-time. Expansions and upgrades of our current systems for tracking gun violence are essential to both address current surges in violence as well as to prevent future occurrences.

First, steps must be taken to support more agencies’ participation in NIBRS. Technical support, implementation support, and financial assistance will all be needed to help police departments adopt and implement this new system. Additionally, because the submission of this data is voluntary, federal and state governments should provide additional incentives for police departments to submit this crucial data.

Improving collection of data on nonfatal shootings is also critical. In 2020, after Congress appropriated $25 million dollars for gun violence research at the CDC and National Institutes of Health (NIH), the CDC started an initiative with 10 state health departments known as Firearm Injury Surveillance Through Emergency Rooms (FASTER) to capture near-real-time data on emergency visits for nonfatal firearm injuries.112 Additional federal funding for gun violence research at the CDC could help expand this program to more states as one way of improving collection of nonfatal shooting data. Critically, in March 2022, the FBI accepted changes to the NIBRS system which will allow victims of shootings to be disaggregated from victims of non-shooting firearm crimes, such as firearm threats. Participating agencies are expected to implement these changes by 2023.

Prioritizing the collection of nonfatal shooting data through both emergency department surveillance and NIBRS is important. Data collected through emergency departments will likely better describe victim characteristics, while crime data generally provides important details on offender characteristics. Collecting quality nonfatal shooting data through both emergency departments and crime data reporting would allow researchers to link these datasets to provide a more complete picture of the characteristics of nonfatal shootings.

It is critical that steps are taken to improve not just the quality of this data, but also the timeliness. Efforts should be made to collect and release closer-to-real-time data on both gun homicides and nonfatal shootings. This data should be accessible to researchers and other stakeholders to ensure that increases in gun violence can be mitigated early, before widespread escalation.

In the absence of more coordinated federal systems, cities can also play a role in helping to increase data transparency and better monitor gun violence trends. Several, though not all, police departments track nonfatal shootings, though very few departments regularly release this information publicly. Cities like Milwaukee113 and Cincinnati114 have dashboards which provide timely data on fatal and nonfatal shootings. Other cities, like New York,115 provide this same data through detailed, frequently updated spreadsheets; Chicago116 and Philadelphia117 publish both spreadsheets and a more user-friendly dashboard.

To be clear, collecting better data alone will not solve this crisis. Improved data collection efforts must inform action in order to reduce gun violence. However, implementing solutions without fully understanding the problem to be addressed is not the answer either. Better data collection will guide efforts to address gun violence and provide us with critical feedback about what is successfully helping to prevent violence.

Conclusion

Over the last two years, Americans have gotten a crash course in public health. Public health terms like “contact tracing” and “physical distancing” have entered our collective lexicon as these practices have been used to reduce the number of coronavirus cases and mitigate the virus’s burden on our healthcare system. We’ve watched as vaccination campaigns have led to dramatic decreases in COVID-19 deaths and severe illness,120 and scientists have developed a number of effective treatments that can be used in cases where people do become infected.121 While this pandemic may not yet be over, we have made tremendous progress.

Now it’s time to do the same for gun violence. We must treat this issue like the public health crisis it is, and address it with proven public health approaches. This approach requires taking a serious, honest look at what is currently driving interpersonal gun violence—and what has always driven this problem—and implementing solutions that are responsive to those factors.

Gun violence has been a crisis in too many communities for too long. Skyrocketing gun violence over the last two years has only intensified this epidemic, making communities that have always suffered from this burden the most suffer even more. This moment demands an urgent response—but also one that can be sustained over the long term and that addresses the deeply rooted conditions that account for gun violence in American cities.

This is a moment that calls for bold ideas and the courage to implement them. It is a moment to rethink what community safety means in this country and to make the kinds of investments and reforms that will allow generations of Americans to live lives free from gun violence. Let’s make sure we have the courage to meet it.

SUPPORT GUN SAFETY

We’re in this together. To build a safer America—one where children and parents in every neighborhood can learn, play, work, and worship without fear of gun violence—we need you standing beside us in this fight.

- See, e.g., Richard Rosenfeld and Ernesto Lopez, “Pandemic, Social Unrest, and Crime in U.S. Cities: Year-End 2021 Update,” Council on Criminal Justice, January 2022, https://counciloncj.org/crime-trends-yearend-2021-update/; Jessica H. Beard et al., “Changes in Shooting Incidence in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, between March and November 2020,” JAMA 325, no. 13 (2021): 1327–1328; Dae-Young Kim and Scott W. Phillips, “When COVID-19 and Guns Meet: A Rise in Shootings,” Journal of Criminal Justice 73 (2021); Priya Krishnakumar, Emma Tucker, Ryan Young, and Pamela Kirkland, “Fueled by Gun Violence, Cities Across the US Are Breaking All-time Homicide Records This Year,” CNN, December 12, 2021, https://www.cnn.com/2021/12/12/us/homicides-major-cities-increase-end-of-year-2021/index.html.[↩]

- Aliza Aufrichtig, Lois Beckett, Jan Diehm, and Jamiles Lartey, “Want to Fix Gun Violence in America? Go Local,” The Guardian, January 9, 2017, https://bit.ly/2i6kaKw.[↩]

- Anthony A. Braga, Andrew V. Papachristos, and David M. Hureau, “The Concentration and Stability of Gun Violence at Micro Places in Boston, 1980–2008,” Journal of Quantitative Criminology 26, no. 1 (2010): 33–53.[↩]

- Cities that provide up to date nonfatal shooting data and are analyzed in this section are Baltimore, MD; Chicago, IL; Milwaukee, WI; Nashville, TN; New York, NY; Oakland, CA; Omaha, NE; and Philadelphia, PA.[↩]

- Crime Data Explorer, “Summary Reporting System and National Incident Based Reporting System,” Federal Bureau of Investigation Uniform Crime Report, last accessed February 18, 2022, https://crime-data-explorer.fr.cloud.gov/pages/explorer/crime/crime-trend.[↩]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (WONDER), “Underlying Cause of Death, 1999–2020,” last accessed February 3, 2022, https://wonder.cdc.gov/.[↩][↩]

- Crime Data Explorer, “Summary Reporting System,” Federal Bureau of Investigation Uniform Crime Report, last accessed February 18, 2022, https://crime-data-explorer.fr.cloud.gov/pages/explorer/crime/crime-trend.[↩]

- Richard Rosenfeld and Ernesto Lopez, “Pandemic, Social Unrest, and Crime in U.S. Cities: Year-End 2021 Update,” Council on Criminal Justice, January 2022, https://counciloncj.org/crime-trends-yearend-2021-update/.[↩]

- While Milwaukee’s dashboard provides yearly totals of gun homicides, monthly homicide counts and demographic data are based on combined gun and non-gun homicides. Given that the vast majority of homicides in Milwaukee involved firearms (88% over the last five years), Giffords Law Center analyzed total homicides and nonfatal shootings in Milwaukee.[↩]

- Data for Chicago, New York City, and Philadelphia was obtained through police department and/or open data releases. Data for Milwaukee was obtained through the Milwaukee Homicide Review Commission Dashboard. See, “Violence Reduction—Victims of Homicides and Non-Fatal Shootings,” Chicago Data Portal, City of Chicago, last accessed February 20, 2022, https://data.cityofchicago.org/Public-Safety/Violence-Reduction-Victims-of-Homicides-and-Non-Fa/gumc-mgzr; “NYPD Shooting Incident Data (Historic)” NYC Open Data, City of New York, last accessed February 20, 2022, https://data.cityofnewyork.us/Public-Safety/NYPD-Shooting-Incident-Data-Historic-/833y-fsy8; “Shooting Victims,” Open Data Philly, City of Philadelphia, last accessed January 31, 2022, https://www.opendataphilly.org/dataset/shooting-victims; “Homicide and Nonfatal Shooting Dashboard,” Milwaukee Homicide Review Commission, Medical College of Wisconsin, last accessed February 21, 2022, https://www.mcw.edu/departments/epidemiology/research/milwaukee-homicide-review-commission/reports/dashboards.[↩]

- Based on an average of five most recent years of available data: 2016 to 2020. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (WONDER), “Underlying Cause of Death, 1999–2020,” last accessed February 3, 2022, https://wonder.cdc.gov/.[↩]

- Each of these cities used different categories to describe the race of gun violence victims. Giffords Law Center presented the data as categorized by each city.[↩]

- Jeffrey P. Brantingham et al., “Is the Recent Surge in Violence in American Cities Due to Contagion?” Journal of Criminal Justice 76 (2021).[↩]

- Lauren-Brooke Eisen, Oliver Roeder, and Julia Bowling, “What Caused the Crime Decline?,” The Brennan Center, February 12, 2015, https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/what-caused-crime-decline.[↩]

- Id.[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- German Lopez, “Trump Says Murders Are Up in Democrat-run Cities. They’re Up in Republican-run Cities, Too,” Vox, September 29, 2020, https://www.vox.com/2020/9/29/21493428/presidential-debate-trump-biden-violent-crime-murder-democrats-republicans.[↩]

- Jon Greenberg, “GOP Tweet Misfires in Linking Crime Trends to Democratic Policies,” PolitiFact, July 9, 2021, https://www.politifact.com/factchecks/2021/jul/09/republican-national-committee-republican/gop-tweet-misfires-linking-crime-trends-democratic/.[↩]

- David Klepper and Gary Fields, “Nashville, Nationwide Crime Up: GOP Blames Democrats, but it’s More Complicated Than That,” The Tennessean, June 11, 2021, https://www.tennessean.com/story/news/politics/2021/06/11/republicans-blame-democrats-defund-police-national-crime-increase-2020-fact-check/7641800002/.[↩]

- Based on Giffords Law Center’s analysis of city-level homicide data. Mayoral political affiliation was determined as of June 1, 2020.[↩]

- Fernando Ferreira and Joseph Gyourko, “Do Political Parties Matter? Evidence From US Cities,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 124, no. 1 (2009): 399–422.[↩]

- Boer Deng and Jessica Lussenhop, “George Floyd Death: What US Police Officers Think of Protests,” BBC News, June 26, 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-53159496.[↩]

- Based on percent change in police budget from fiscal year 2020 to fiscal year 2021. For most cities, fiscal years run from July 1 to June 30 of the following calendar year. Giffords Law Center compared police department budgets in the fifty largest cities based on city budget plans. Where possible, adopted or approved spending amounts were used in place of proposed spending amounts. Similarly, where available and applicable, Giffords Law Center attempted to use any approved budget amendments for analysis. Oakland, CA was not included in this analysis, as their budget is compiled over two fiscal years, meaning that there was no separate budget for FY 2020 and FY 2021.[↩]

- In some cities, FY 2021 budgets did see a cut from proposed spending to approved spending. However, this analysis only considered changes that showed increased or decreased spending over the FY 2020 approved, or approved amended, budget.[↩]

- Philip Bump, “Over the Past 60 Years, More Spending on Police Hasn’t Necessarily Meant Less Crime,” Washington Post, June 7, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2020/06/07/over-past-60-years-more-spending-police-hasnt-necessarily-meant-less-crime/.[↩]

- David Weisburd and Malay K. Majmundar (eds.), Proactive Policing: Effects on Crime and Communities, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, National Academies Press, 2018.[↩]

- Sungwoo Cho, Felipe Gonçalves, and Emily Weisburst, “Do Police Make Too Many Arrests? The Effect of Enforcement Pullbacks on Crime,” Institute of Labor Economics, no. 14907 (2021).[↩]

- Aaron Chalfin, David Mitre-Becerril, and Morgan C. Williams, Jr., “Does Proactive Policing Really Increase Major Crime? Accounting for An Ecological Fallacy,” University of Pennsylvania School of Criminology, May 27, 2021, https://davidmitre.netlify.app/research/Draft_Proactive_policing_and_crime_210527.pdf.[↩]

- Andrew Bacher-Hicks and Elijah de la Campa, “The Impact of New York City’s Stop and Frisk Program on Crime: The Case of Police Commanders,” Harvard Kennedy School of Government, January 14, 2020, https://drive.google.com/file/d/1SxbK9_9mPwopEGyAyvJ606jrqCL1rwxT/view.[↩]

- Andrea Cann Chandrasekher, “The Effect of Police Slowdowns on Crime,” American Law and Economics Review 18, no. 2 (2016): 385–437.[↩]

- Steve Chapman, “Don’t Blame Bail Reform For Spike In Violent Crime,” The Pittsburgh-Post Gazette, July 7, 2021, https://www.post-gazette.com/opinion/Op-Ed/2021/07/07/Steve-Chapman-Don-t-blame-bail-reform-for-violent-crime/stories/202107070009.[↩]