Implementation Toolkit for Gun Safety Laws

Gun violence is a major public health crisis that kills nearly 40,000 Americans each year. Tens of thousands more are shot and survive, many suffering lifelong physical injuries and trauma.

Gun violence is undeniably a public health issue, and it’s also a legal issue. Gun safety laws are critical to prevention and intervention. But lifesaving policies need to be effectively, fairly, and safely implemented in order to make a difference. The goal of the gun safety movement is to save lives, not simply to pass laws. Effective implementation is central to this effort.

Executive Summary

Giffords Law Center is deeply committed to working with policymakers and stakeholders to identify key components of effective implementation. Our Implementation Toolkit offers information and resources to assist communities with this important and often overlooked aspect of gun violence prevention policies.

Examples of obstacles to effective implementation include:

- Missing input from key stakeholders in identifying the problem and solutions

- Lack of clarity in the policy itself and/or frequent changes and amendments

- Limited education and training for stakeholders responsible for implementation

- Underfunding necessary resources, including technology, staffing, and facilities

- Lack of diverse input and groundwork to build support and coalitions

- Lack of clarity about how to measure success and absence of focus on data collection

Key components of effective implementation include:

- Developing equitable and inclusive policies with diverse input

- Clarifying purpose, goals, opportunities, and challenges

- Developing and documenting policies, practices, and procedures

- Spreading the word through education, training, and public information sharing

- Measuring success and avoiding pitfalls

Related resources:

- Implementation Checklist: This fillable PDF can be shared with key stakeholders and used to emphasize collaboration, ensure diverse voices are participating in the process, and consider opportunities and challenges.

- Action Planning Template: This worksheet can be useful for groups discussing next steps for their communities to more fully implement gun safety policies, procedures, and protocols.

- Brochure: California uses this brochure to share information about the range of options available for reducing risks when someone has access to firearms and is exhibiting dangerous behavior. The pocket-sized brochure can serve as a template for other communities.

- Webinars: This webinar from March 2020 provides details around implementation of California’s Gun Violence Restraining Order, while this webinar from October 2020 highlights opportunities to address domestic violence as part of community violence prevention work.

- Implementation page: This landing page for Giffords Law Center’s implementation work is intended to serve as an overview of the “why” and the “how” of gun safety law implementation and a complement to this toolkit.

Implementation is a critical component of ensuring that gun safety laws work fairly and effectively to prevent violence. We hope this toolkit will be a valuable resource for those who share this goal.

Introduction

On June 19, 2019, 26-year-old Sacramento Police Officer Tara O’Sullivan was helping a woman who had experienced domestic violence gather her belongings from her home. Suddenly, a man inside the home opened fire, hitting Officer O’Sullivan. He continued shooting for almost 30 minutes.

Officer O’Sullivan died later that day, after being on the job for just six months. The woman who was seeking protection also experienced the trauma of witnessing this event after living with domestic violence.

The man charged in the killing of Officer O’Sullivan had a long history of violence: in 1998, he was arrested and sentenced to three years probation as a result of domestic violence. In 2003, he was again arrested for domestic violence against his then-wife. In 2007, he was taken to court and accused of domestic violence (that case was later dismissed). He was again arrested in November 2018 for assault and battery. At the time of Officer O’Sullivan’s death, there was a bench warrant out for his arrest for not appearing at a hearing.

In the aftermath of Officer O’Sullivan’s death, questions arose about what could have been done to prevent this tragic outcome:

- What steps were taken, or could have been taken, to better protect the woman experiencing domestic violence and others from violence, both that day and prior to this tragedy?

- Given the shooter’s history of violence, was he prohibited under California or federal law from owning or possessing firearms?

- Before going to the home, could the officers have known whether the person living there owned firearms or was prohibited from having them?

- Were there policies, procedures, or practices that could have been more effectively implemented to decrease risk?

Good policies combined with effective implementation can’t prevent every tragedy. But there are ways to reduce risk and increase safety, and communities nationwide should be taking steps to put in place policies policies that will reduce risk and save lives.

This toolkit is designed to support a crucial and often overlooked aspect of gun violence prevention: implementation. From the beginning of the policy development process, when communities, advocates, and other stakeholders are exploring lifesaving policy concepts and drafting legislation, thought should be given to why the policy is being developed, how it will be applied, and what resources will be necessary to enable it to live up to its promise.

The goal of the gun safety movement is to save lives, not simply to pass laws.

Making policies accessible and getting the word out about them are both crucial steps; equally important is ensuring that a given policy doesn’t create negative or unintended consequences that do more harm than good. This toolkit is designed for violence prevention advocates, policymakers, courts, social service providers, law enforcement agencies, and others responsible for implementation of gun safety policies to help them ensure robust, thoughtful, and effective implementation.

MEDIA REQUESTS

Our experts can speak to the full spectrum of gun violence prevention issues. Have a question? Email us at media@giffords.org.

Contact

Why Implementation?

Gun violence is a complex problem that includes firearm suicide, mass shootings, police-involved shootings, community violence, and domestic violence. As such, gun violence must be addressed with a range of solutions. What might be most effective for addressing suicide may actually increase risk for those experiencing domestic violence, if, for example, firearms are removed but nothing is done to address other forms of abuse.

Giffords Law Center has spent the past 28 years drafting and advocating for legislation to address these critical issues. We recognize that our advocacy efforts are most effective when laws are applied equitably and effectively and include input from a diverse set of stakeholders working collaboratively. When policies and procedures are properly implemented, communities benefit from the promise that originally led to support for those approaches.

When implementation is ineffective, on the other hand, often the policy itself is seen as inadequate. Poor or limited implementation is costly—not only financially, but also because it can result in loss of life and undermine the impact of hard-fought victories. To ensure the greatest likelihood of success, implementation needs to be considered as early in the process as possible. The question that must be asked is: How do we develop gun safety policies in ways that make robust implementation possible?

Examples of obstacles to effective implementation include:

- Missing input from key stakeholders in identifying the problem and solutions

- Lack of clarity in the policy itself and/or frequent changes and amendments

- Limited education and training for stakeholders responsible for implementation

- Underfunding necessary resources, including technology, staffing, and facilities

- Lack of diverse input and groundwork to build support and coalitions

- Lack of clarity about how to measure success and absence of focus on data collection

Fortunately, these problems can be addressed through thoughtful, comprehensive processes put in place from the outset. This often involves gathering a diverse array of stakeholders responsible for drafting and implementing policies, some of whom don’t normally interact with one another.

In November and December 2019, Giffords Law Center hosted two convenings—one in Los Angeles and one in San Francisco—that brought together over 300 participants from a wide range of community and governmental organizations to discuss how to more fully implement California’s existing firearms prohibitions. Attendees included judges, court administrators, attorneys, probation officers, prosecutors, public defenders, community violence prevention and domestic violence victim advocates, public and mental health professionals, gun violence survivors, and policymakers.

The convenings, based on the Coordinated Community Response approach and Family Violence Councils, featured presentations on model approaches, workshops providing legal context and information about local procedures, and community action planning. Many of those responsible for implementing the various approaches to gun violence prevention had never met before, but the convenings gave participants greater clarity about the entirety of the process, breaking down silos that had previously been barriers to communication and collaboration.

Example: The Importance of Implementation for Background Checks

The background checks process is key to the effectiveness of firearms prohibitions. If someone becomes prohibited from accessing firearms and attempts to purchase a gun through an otherwise legal process, the seller should discover that the person is not permitted to own a firearm. This requires 1) systems that make background checks possible and 2) requirements that background checks be conducted prior to a sale.

Effective implementation at all points in this process is absolutely critical. Courts, psychiatric facilities, law enforcement—everyone responsible for inputting information at the point someone becomes prohibited—must provide accurate information to the state and federal databases. Studies show that efforts to improve the quality and completeness of records in the background check system can help prevent acts of violence.

The NICS Improvement Amendments Act of 2007 required comprehensive records reporting to NICS, particularly related to mental health records. By adding these records, those who were prohibited from purchasing a firearm because of a mental health disqualification would be denied if they attempted to purchase and a background check was run. Subsequent to adding the records, Connecticut, for example, saw a 53% decrease in the risk of arrest for violent crimes compared to people who were not disqualified from having a firearm because of only a voluntary mental health hospitalization.

The output must similarly be accessed effectively, appropriately, and consistently at the time someone attempts to complete a purchase. Unfortunately, a dangerous gap in our federal gun laws lets people buy guns without passing a background check. Under current law, unlicensed sellers—people who sell guns online, at gun shows, or anywhere else without a federal dealer’s license—can transfer firearms without having to run a background check.

Source

Matthew Miller, Lisa Hepburn & Deborah Azrael, “Firearm Acquisition Without Background Checks,” Annals of Internal Medicine 166, no. 4 (2017): 233–239.

Because of this loophole, people who are subject to domestic violence convictions or court orders, people who have been convicted of violent crimes, and people ineligible to possess firearms for mental health reasons can easily buy guns from unlicensed sellers with no background check in most states. In fact, an estimated 22% of US gun owners acquired their most recent firearm without a background check—which translates to millions of Americans acquiring millions of guns, no questions asked, each year.

When background checks are required, include accurate information, and properly enforced—in other words, fully implemented—they can help keep guns out of the hands of people prohibited from having them. When this system fails, this failure can have dangerous and sometimes deadly consequences:

- In 2014, a gunman in West Virginia killed four people, including his ex-girlfriend, with a gun he purchased from an online seller without a background check. He was prohibited from purchasing firearms due to multiple felony convictions.

- In 2017, a former serviceman killed more than two dozen people at a church in Sutherland Springs, Texas. A federal judge recently found the Air Force was 60% responsible for the shooting because the agency failed to put the man’s criminal history into the national database that would have prevented him from purchasing firearms. His prior history included assaulting his ex-wife and cracking his stepson’s skull.

- In 2018, a man in Appleton, Wisconsin, who was prohibited from purchasing a gun because he was out on bond for a firearm-related felony purchased a firearm from an unlicensed seller on Armslist.com. The next day he used the gun to kill his wife.

- In 2019, a man fatally shot seven people and wounded 25 others in West Texas. The shooter previously failed a criminal background check but was able to obtain an AR-style weapon from an unlicensed seller.

Example: The Importance of Implementation for Civil Restraining Orders

Civil restraining orders, which can be requested by members of the public and in some instances, law enforcement, prevent a “restrained party” from engaging in certain behaviors. Domestic violence restraining or protective orders, which exist in all states, are the most well-known example; implementation in this area provides another example of some of the pitfalls and possibilities for improvement around firearm prohibitions associated with these orders.

Federal law prohibits purchase and possession of firearms and ammunition by people who have been convicted of domestic violence or are subject to certain domestic violence protective orders. However, few jurisdictions have policies in place to ensure compliance. This involves providing information to restrained parties or those convicted about how to relinquish firearms and adhere to the prohibitions; setting review hearings to check on compliance; and requiring proof of relinquishment of firearms. Too often, prohibitions are put in place without follow-up to ensure that firearms possessed by a now-prohibited person are relinquished or surrendered. Consequently, victims may be told that the person who has harmed them cannot have firearms but not have any recourse when that person doesn’t comply.

According to California’s Department of Justice Armed Prohibited Persons System, as of January 1, 2021, over 23,500 people in the state who have become prohibited from owning firearms are listed as still possessing them. Some include domestic violence cases. There are likely many more people in the state subject to civil restraining orders or otherwise prohibited who continue to own or keep firearms because the Department of Justice does not have information about their prohibited firearm ownership. This puts protected parties and the public generally at significant risk.

Effective implementation of domestic violence orders should include:

- providing information to restrained parties about how to comply with local relinquishment procedures

- ensuring law enforcement takes appropriate risk-reduction steps when domestic violence orders are served and provides storage for firearms

- reviewing compliance at subsequent hearings if evidence of compliance is missing

- improving coordination between community-based organizations and the legal system

Another example of the critical role of implementation in civil matters is California’s Gun Violence Restraining Order (GVRO) law. The GVRO allows civil courts to issue an order that temporarily prevents someone at risk of harming themselves or others from accessing firearms. GVROs (also known as extreme risk protection order or red flag laws) were used to intervene in hundreds of cases of threatened violence or harm in California from 2016 to 2019—a relatively small number for a state with around 12,000 gun deaths during this time frame. Over the last few years, some advocates raised concerns that the law was being underutilized because of lack of familiarity and public education.

Upon further examination, it became clear that the complexity of introducing a new law that differed significantly from other firearm-prohibiting or risk-reduction remedies likely contributed to limited use of the GVRO. Many California localities have a variety of efforts in place to reduce risks without utilizing court processes which may be useful in some situations. Additionally, the state already had longstanding firearm prohibiting civil restraining orders that had similarly not been fully implemented. Helpful local procedures—such as informing those who became prohibited about how to comply, providing families with information about options when they are concerned about a loved one at risk, and ensuring local law enforcement had processes in place for storing and returning firearms—were all somewhat limited.

GVROs also expanded the role that law enforcement plays in the civil restraining order context. Law enforcement officers were given the ability to obtain not only emergency orders but also temporary and longer term orders after hearings, requiring officers to go to court to petition for an order, a new expectation that required training and protocols.

Because of the other firearm prohibiting tools available in the state, it is appropriate that the GVRO will continue to be used for the narrow set of circumstances for which it was intended. No other orders or remedies that can be critical when someone is violent—such an order to stay away from a particular person or obtain counseling or other services—are associated with the GVRO. Additionally, because it is a tool that includes criminal penalties for violations (as is the case with other restraining orders), some family members and others may be less inclined to pursue this remedy rather than other risk-reducing approaches such as voluntary relinquishment, counseling, or other means of planning for safety. The National Domestic Violence Hotline offers an interactive safety planning tool, which highlights the need to have a variety of options to help reduce risk. Similar safety planning approaches have been developed for medical professionals and may be helpful for individuals who provide crisis, legal, and health care services.

Effective implementation of firearm risk reduction policies should include:

- developing a range of violence prevention policies with a diverse set of stakeholders and spreading the word about the range of options

- focusing on reduction of violence and harmful outcomes rather than measuring success by counting the number of orders issued

- understanding the broader legal and social contexts to identify gaps and opportunities for reducing risk, while taking into account the existing scheme of laws

We know that when we collectively and effectively implement well-considered approaches, we can prevent gun violence. The following is an example of what effective implementation can look like.

Effective Implementation in King County, Washington

Source

JC Campbell, et al., “Risk Factors for Femicide in Abusive Relationships: Results from a Multisite Case Control Study,” American Journal of Public Health 93, no.7 (2003): 1089–1097.

Domestic violence is a leading cause of injury for women in the US between the ages of 15 and 44. Research shows that female intimate partners are five times more likely to be killed by a male partner when a firearm is present. The deadly nexus of firearms and intimate partner violence has been well-known for decades and there is increasing recognition that firearms are frequently used to coerce and threaten partners, former partners, and other family members. In many instances, mass shootings have been carried out by individuals who perpetrated domestic violence and should not have had access to firearms. Legal system approaches, along with public health efforts and community-based efforts to address the underlying causes of violence, are key to reducing these risks.

At the federal level, the Gun Control Act of 1968 prohibits certain people from owning, possessing, or receiving firearms. Since 1994, prohibitions included in the Violence Against Women Act have specified that individuals convicted of domestic violence felonies or subject to domestic violence restraining orders should not have access to firearms. Unfortunately, these prohibitions do not include language around relinquishment or surrender of existing firearms. Some jurisdictions across the country have addressed that gap by adopting procedures to ensure that firearms are in fact turned over and stored or sold while the order is in place. Seattle’s Regional Domestic Violence Firearms Unit is one such example.

Domestic violence homicide perpetrators use firearms more often than all other weapons combined.

A 2013–2014 study found that 54% of perpetrators in domestic violence-related shooting deaths were prohibited from owning firearms under Washington State law. The unit notes that in the state, “domestic violence homicide perpetrators use firearms more often than all other weapons combined.” Recognizing the need to reduce the time between an order and relinquishment of firearms, the King County Prosecutor’s Office worked with partners across the region to launch a unit dedicated to improving the handling of these cases.

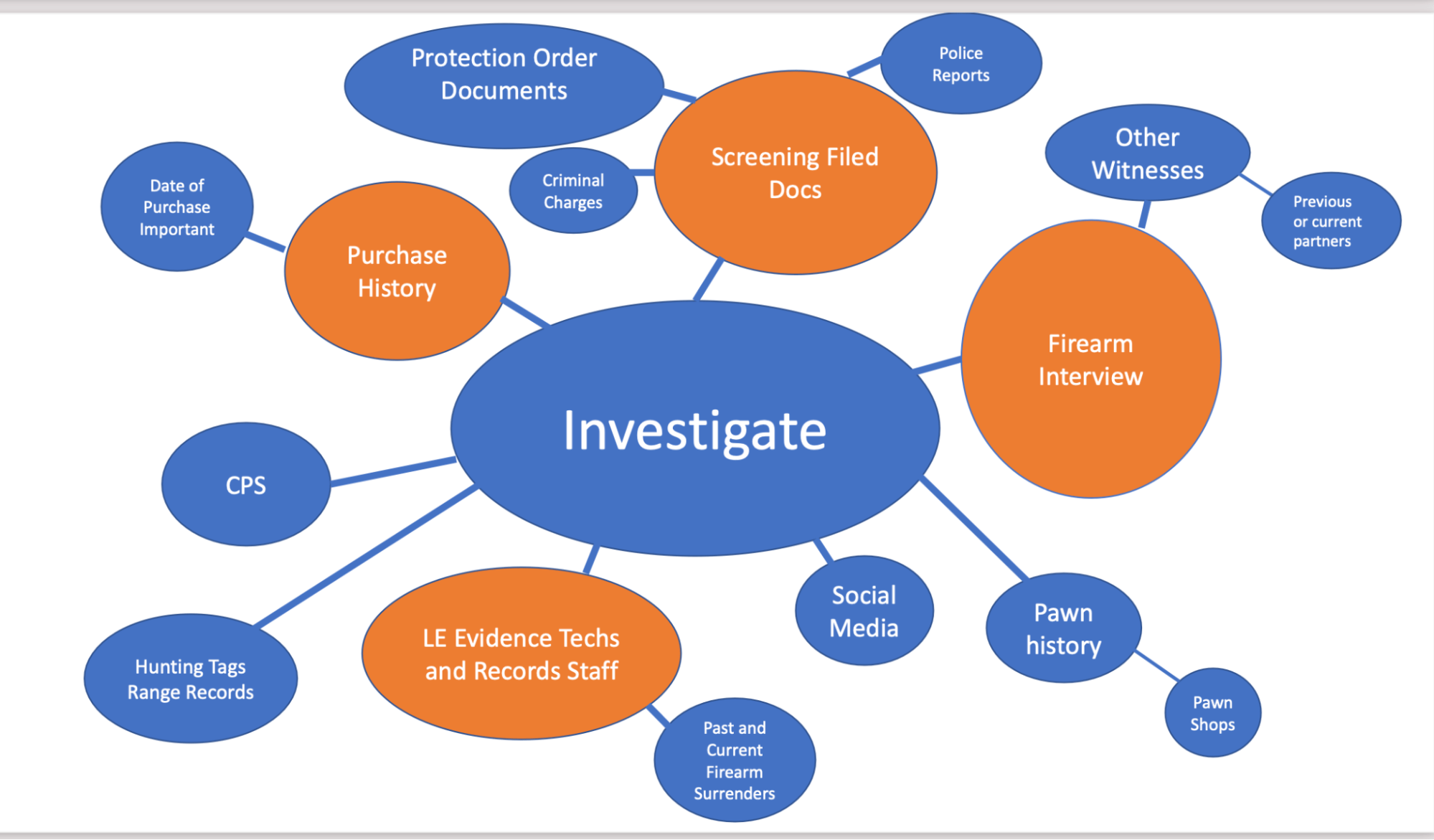

The unit is “designed to be multidisciplinary and interjurisdictional in nature to respond to the reality that firearms cross jurisdictional lines and span both civil and criminal cases.” Its work includes investigating, advocating on behalf of those who have experienced harm, and sharing or reporting information as needed. Development of the unit and its policies and procedures required extensive coordination, meetings, and discussions. Those involved in the process spoke about how important it was to think through processes carefully and methodically. Since the unit was launched on January 1, 2018, its efforts have resulted in many more firearms being relinquished and an increase in compliance with firearm-prohibiting orders across the region.

The graphics below show the complexity of the connections and relationships involved with developing and implementing the policies and procedures associated with firearms relinquishment in the area. The unit has formal collaborative agreements between the King County Prosecuting Attorney’s Office, Seattle City Attorney’s Office, King County Sheriff’s Office, and the Seattle Police Department. They also work with every law enforcement agency that has jurisdiction over the respondent to help facilitate information-sharing to promote safe recovery and compliance.

Key Components of Implementation

In most cases, the “how” of the approach used to make policies work is just as important as the policy itself. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) has established a model for policy development and implementation similar to the approach Giffords takes in our work. The approach that the CDC recommends is “systematic…like a journey.” The CDC notes that similar to taking a trip, with policies, “you need to decide where you want to go, weigh the pros and cons of different destinations and routes, plan your itinerary, and then travel to your destination.”

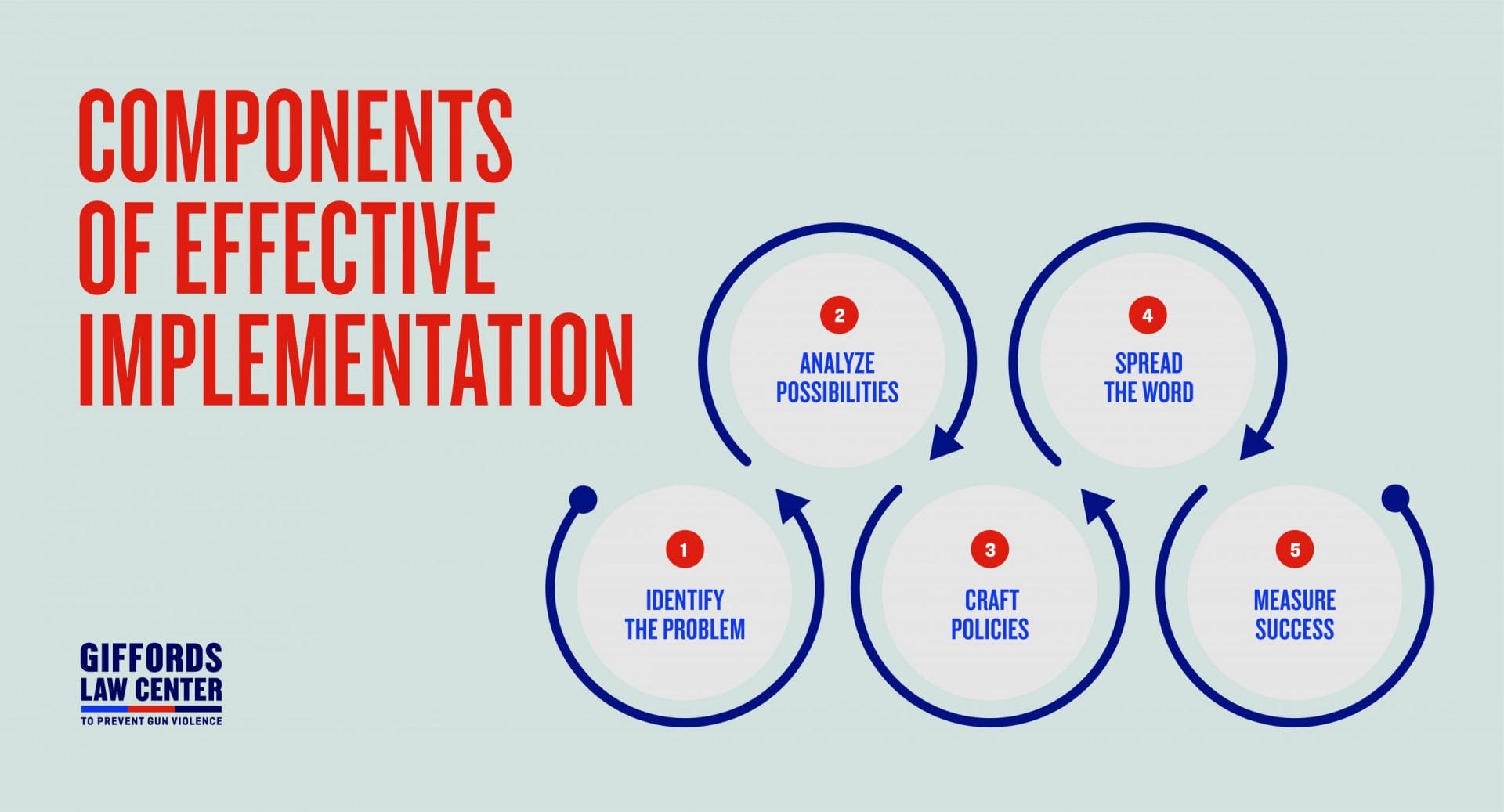

The core of successful implementation is engagement of stakeholders. Ensuring that the right people are included in the process early and throughout is critical to the steps that follow: identifying the problem, analyzing possibilities, crafting policies, spreading the word, and measuring success. A commitment to diversity, equity, and inclusion should be infused throughout the process.

Step 1: Gather Diverse Input and Identify the Problem

Gun violence prevention policies are most effective when developed by a diverse set of stakeholders. Research shows that in general, problem-solving discussions benefit from “informational diversity,” where people can offer varied perspectives and opinions. Because social segregation, institutionalized racism, and biases based on gender, culture, ethnicity, and mental health status influence our exposure to and risk of firearm violence, it’s especially important that these policy discussions involve a diversity of perspectives.

These characteristics and experiences also shape the level of trust that individuals and communities have in public institutions. The Institute for the Advancement of the American Legal System’s 2020 report provides useful insights: while participants agree courts are important, “noting the role [they] play in preserving a civil society, maintaining democracy, or providing a mechanism for justice,” a majority “expressed concerns about the fairness of the current civil process, many of which centered on perceptions of systemic racial or gender bias, differential treatment based on financial ability, and judicial biases.”

Recent research in California on domestic violence and racism found that “two-thirds of Californians think if they were assaulted by a partner and called the police, they would help the situation. But many, especially Black Californians, say they would not go to the police if assaulted or feel the police would make the situation worse.”

For these reasons, it’s critical that not all risk reduction options rely on systems that aren’t experienced as equally accessible. If, for example, civil restraining orders that include firearms prohibitions also require filing fees or hiring an attorney to navigate the court process, that remedy will not be equitably available to everyone. Without diverse input early in the process, policy solutions and problem identification may rely too heavily on law enforcement or the courts at the expense of trusted community-based approaches. Additionally, as is true with other legal remedies, gun safety policies need to be designed to avoid disparate impact, biases, and unintended negative consequences.

Taking aninclusive approach to implementation necessitates broadening the scope of stakeholders to include survivors of gun violence, family members of victims, first responders, and those responsible for providing a given service or procedure. Additionally, the drafting and advocacy process itself should be as inclusive and accessible as possible. For example, when meetings include child care, interpreters, and remote participation options, it is more likely that processes will involve a range of community members.

This process may sometimes appropriately include judges, but care must be taken to protect their neutrality and avoid ethical concerns. Inviting both prosecutors and defense attorneys, advocates representing different sides of an issue, and court administrators can more effectively support this kind of effort. With some professional communities, it’s important to ensure that the leader of the organization is at the table; for others, it’s crucial to include those interacting most often with the public or using the technology that will be required. For example, clerks play an important and often under-appreciated role in many law enforcement agencies. Ensuring that clerks are consulted on the best ways to submit or obtain information can help support more effective implementation.

During this early part of the process, it can be helpful to look to other jurisdictions and communities for promising practices. As part of that effort,it’s important to identify what makes one approach better than another. Do those implementing the approach elsewhere have experience with the populations or community they are sharing their approach with? Have they considered how to avoid detrimental impacts on communities of color, victims, and others? Consider finding a diverse set of peers in various professions to champion a wide variety of approaches when looking for good examples from other places.

Step 2: Analyze Policy Possibilities by Clarifying Purpose, Goals, and Challenges

When developing policies, communities should make an effort to understand the scope of the problem before analyzing possible solutions. Ideally, this will involve not only carefully identifying the problem, but also existing resources and obstacles to implementation. Recognizing that jurisdictions are diverse legally, culturally, and procedurally, advocates must understand what local expectations and challenges are before embarking on a particular approach. This information-gathering process is necessary both at the beginning as well as throughout the development and implementation of policies.

Advocates should make every effort to do the following:

- Seek to ensure clarity as early as possible in the process. This means analyzing proposed policies to ensure that the language and concepts are easily understandable and being able to explain the “use cases” for a particular policy. This could involve, for example, sharing information about the importance of entering prohibited information into government databases to increase the effectiveness of background checks, including clear steps detailing who needs to do what, when. This also means ensuring that these individuals have access to the necessary training and technology.

- Discuss and analyze approaches to avoid unintended consequences. For example, if therapists can seek extreme risk protection orders against patients and have to warn clients about this possibility, will help-seeking decrease? And if law enforcement officers are obtaining these orders instead of pursuing domestic violence charges, will fewer domestic violence restraining orders be issued? This could inadvertently result in decreased safety for survivors who may need broader protections that include requiring the person who has perpetrated abuse to move out, pay child or spousal support, or attend a program to help address violent behavior.

- Make a plan for adequate and equitable funding. Government agencies, social service providers, and community-based organizations all have a significant role to play in implementing policies. Without adequate funding, those with access to resources can easily end up dominating implementation—the how, when, why, media coverage, use cases, websites, materials—which will end up marginalizing or silencing those with more limited access to resources. Thoughtful funding can help address and improve equity by allocating resources in ways that have the most effective impact.

- When developing policies, pursue the most accessible approach. For example, California enacted a policy that allows respondents to consent to the issuance of a GVRO rather than appear in court. This approach may make it easier for those who are willing to surrender their firearms for a temporary, limited period of time to do so without having to navigate the court process. Various titles for the form were considered, some of which could have been read more expansively than the title that was eventually adopted: “Consent to gun violence restraining order and surrender of firearms.” By focusing on the specific policy, not overstating the application of the order, and making it easy to comply, individuals who would otherwise see this remedy as intrusive might see it as useful.

Step 3: Craft and Document Policies, Practices, and Procedures

In the field of social change, change itself is inevitable: turnover in leadership, the impact of new laws, and the effects of a particular tragedy can all reveal gaps in current policies. Sometimes the process of developing new policies, practices, and procedures is as important as the actual documents that result: relationships can be developed, problems may be identified, and more solutions may be uncovered. Checklists can be particularly helpful in terms of keeping decision-makers on track and ensuring that stakeholders guard against implicit bias and inconsistent application of policies.

Many of us think of legislation or statutory changes when we think about formalizing policies. While adopting gun safety laws is a critical component of violence prevention, we should take an expansive approach to policy development when it comes to implementation. Consider whether administrative regulations, local court rules or forms, clinic intake procedures, or social service programs might elicit information designed to reduce firearm risk. At Giffords Law Center, we offer technical assistance that includes providing examples and helping to draft and develop language and policies that make sense for specific situations and jurisdictions.

Additionally, if local protocols and procedures are critical for effective implementation, consider how those will be developed and shared. If there is a task force, coalition, or other opportunity to help shape those policies, consider who can join those groups and whether violence prevention advocates will be included. If there is a public comment period, distribute that information widely so that those developing procedures can receive comprehensive information from diverse sources.

HERE TO HELP

Interested in partnering with us to draft, enact, or implement lifesaving gun safety legislation in your community? Our attorneys provide free assistance to lawmakers, public officials, and advocates working toward solutions to the gun violence crisis.

CONTACT US

Step 4: Spread the Word Through Education, Training, and Public Information-Sharing

Once policies are put in place, it can be challenging to ensure that information about these changes reach the people who most need them. A diverse group of stakeholders can assist with disseminating information, especially if they have been involved early in the process. For example, in some communities and with certain policies, it may be important to ensure that clergy, teachers, counselors, and others who interact with families have information about how to address concerns about potential firearms violence. Involving them in identifying the problem and crafting solutions will make it easier to implement policies once they are enacted.

In other situations, it will be important that court staff and leadership, probation, law enforcement, and other public officials have a deep understanding of a new law or policy. These professions all have their own sources of information and ways of communicating. They may also have specific regulations, forms, and training requirements, each of which provides an opportunity to gather input, shape procedures, and share information about new policies.

It is critical to avoid disseminating misinformation that can confuse stakeholders. Legal policy is often nuanced and changes over time through court decisions, statutory amendments, and interpretations through rules and regulations. Trainings should be conducted by people who understand the complexity of the jurisdiction’s legal framework and should not focus solely on the new laws, but instead place new provisions in the context of existing law. Any public-facing materials should similarly avoid advocating for a single legal remedy and should instead provide referrals to safety planning and legal services. Jurisdictions might also consider developing standardized materials and a “train the trainers” program to help keep information consistent and accurate.

Consider the following options for spreading awareness:

- Newsletters/specialized publications: Utilize the pre-existing regular publications of community-based organizations, professional associations, religious institutions, law enforcement, social service providers, and government entities, which can be useful vehicles for getting information out about a new law or policy change.

- Training: Find out who provides the training that key stakeholders might be expected to attend. Are there opportunities to attend, present, or help design content? Are the messages accurate and unbiased? Are there handouts that could be updated or developed to improve the information that attendees have at their fingertips?

- Websites: Ensure that people that know there are a range of options and hotlines, attorneys, and others available to assist in specific cases and steer clear of recommending one legal remedy or approach over another. If possible, websites should be available in multiple languages and information should be presented in plain, accessible language or use terminology relevant to that audience.

- Convenings: Host or attend gatherings in the form of meetings, conferences, retreats, or convenings, which can provide time and space for key stakeholders to develop greater familiarity with others working in related areas, build or improve relationships, and make plans for effective implementation. When possible, these events should include action planning so that participants leave with practical next steps.

- Coalitions: Develop diverse coalitions across issues so that violence prevention efforts are not siloed. Community violence organizations working with families may find it beneficial to connect with those working on domestic violence, who may also find it helpful to work with those seeking to prevent suicide, unintentional shootings, and police-involved violence.

- Publications: Co-write articles with organizations and people who are part of the coalition needed to get the word out to key audiences; check in with publications about their commitment to including diverse voices and commit to ensuring those writing and being published reflect the range of people and communities impacted by policies being considered or already enacted.

- Social Media: Consider what images are used to raise awareness and what platforms are selected. Become familiar with the diverse range of places and people who might be interested in learning more about this policy.

Programs designed to solicit input or increase awareness about a new policy should be financially accessible and promoted in a variety of ways. Providing materials in multiple languages, developing forms and messages in plain language, and recognizing the various ways that people access information will be more likely to result in successful implementation.

Step 5: Measure Success and Avoid Pitfalls

After the hard work done to identify problems and develop remedies, it’s critical that stakeholders are able to measure the changes that occur. Ideally, strategizing about policy development will include considering what success will look like. Using checklists can help identify these elements and influence key aspects that need to be measured at various points in the process.

For example, if it is important for certain stakeholders or implementors to be informed about a policy change, a community might measure success by tracking the number of trainings on the topic or training participants who have learned about the new legislation or procedures. Quantitative data where available can help paint a picture of how the actions the community is taking have made a difference. Another measurable way to document success might include identifying increases or reallocation of resources to better support violence prevention and intervention programs.

Success might also be measured by gathering qualitative information about how a policy or program is being received and implemented. For example, evidence that there is a lot of support for a particular approach or the lack of vocal resistance might be an important indicator of success. The more we can understand about how policy developments have succeeded (or failed), the more we can recognize what works and avoid unintended consequences in the future.

When considering how to measure success, there are some pitfalls to consider and avoid, including:

- Measuring successful implementation by setting arbitrary benchmarks. In some instances—for example, where a remedy has been underutilized—it may be helpful to gather information on why that has happened and whether there are other remedies or approaches that have been used instead. There is no clear formula or benchmark that will tell us whether a single policy is successful. Information about a variety of approaches and remedies, and data on how well-informed people are about a policy, may be more useful when reporting on implementation rather than counting how often a remedy was used.

- Focusing on a single remedy in isolation or as the best or only remedy. There are criminal, civil, and other approaches that may make more sense or be safer. There may be approaches that do not involve law enforcement or the courts. Without all available options on the table, it will be difficult to ensure that the choices being made are the right one for a particular community or situation.

- Using polarizing terminology. There is significant support across the political spectrum for gun safety policies. Consider taking concrete steps to avoid using language that criticizes gun owners, veterans, or others for whom firearms may be important, as well as language that suggests all those who own guns are inherently dangerous. Also, avoid using language that demonizes or marginalizes certain groups of stakeholders (“dangerous hands,” “the mentally ill,” “criminals”). Language matters, and it can make the implementation process more or less inclusive.

OUR STORIES

We’re youth activists, survivors, doctors, and gun owners. We’re united in the fight to end gun violence.

Read More

Challenges and Recommendations

Sometimes, implementation is hampered by unforeseen challenges. This list is intended to provide guidance and recommendations for how to address some of these challenges.

Challenge: Lack of clarity in the statute. Stakeholders disagree over what is intended by the law and who should guide implementation.

Recommendation: Consider creating a multidisciplinary stakeholder working group to discuss what success looks like. Make sure participants bring diverse perspectives to the discussion and that membership itself is diverse around race, culture, LGBTQ+ identity, involvement in mental health service delivery, tribal affiliation, and other characteristics that reflect communities impacted by the law. Include attorneys and others involved with interpretation and court-connected implementation, if relevant, to create consistent approaches. The work and decisions of this group should be documented and available to the public to assist with understanding how policies and procedures were developed and intended to be implemented.

Challenge: Limited or lack of resources. If no funding is allocated in the original bill, stakeholders may struggle to effectively implement the law.

Recommendation: Identify funding needs and opportunities to advocate for appropriate resources. Explore whether any currently funded approaches could be reworked to include this new policy area. Build coalitions and partnerships with others who may be able to leverage funds or resources that would not otherwise be available. Sometimes existing funding or resources can be tapped for new policy requirements. For example, if there is an existing, related training already in place, perhaps new approaches can be built into that training without requiring additional funding. If limited funding is available, consider establishing a pilot project in one location that others can then learn from.

Challenge: Law isn’t widely known or well-understood. Some new legal remedies may be unfamiliar to key stakeholders who don’t have the training or context to successfully implement the law.

Recommendation: Partner with others in relevant professions to develop responsive training opportunities. Connect local stakeholders with peers in jurisdictions that are similar and have implemented related approaches. To determine who should have what kind of training, identify key ways the public might end up needing the particular remedy and who they might interact with. Produce materials for stakeholders and those who need to know about the law, such as the brochure linked to at the end of the report.

Challenge: Safe policies for removal and storage of firearms are not in place or are inconsistent statewide. This can cause confusion across jurisdictions and create unnecessary duplication of limited resources.

Recommendation: Create clear policies and procedures, and help disseminate policies from other jurisdictions. Coordinate and learn promising practices from each other through well-documented policies and procedures. It may be useful to consider whether there are regional or statewide organizations, departments, or other entities that can assist in taking a broader and more comprehensive approach to developing, disseminating, and implementing policies. For example, would the attorney general, state Department of Justice, or other professional associations for law enforcement, attorneys, or local leadership be able to assist with support around consistency across jurisdictions?

Challenge: Limited data and ability to measure success. Many communities have limited information about how policies are being applied.

Recommendation: Data collection should be built into policies and procedures so that budget requests and areas for improvement can be identified, as can any unintended negative or disproportionate impact. Start by identifying key indicators of success, discussing with working groups and partners, and finding ways to collect information early and throughout the implementation process. Consider whether a local college or university or organization may be able to assist with research efforts.

When we work together to identify gaps, promising practices, and missing resources, and develop policies with input from a wide array of stakeholders, we can more effectively implement approaches to prevent lethal outcomes and serious injuries. Whether it’s enacting laws that recognize the intersection between various forms of violence and firearms, allocating federal resources to more effectively prevent community violence, or conducting research to learn more about what’s working, a focus on robust, fair, and responsive implementation is critical.

HERE TO HELP

Interested in partnering with us to draft, enact, or implement lifesaving gun safety legislation in your community? Our attorneys provide free assistance to lawmakers, public officials, and advocates working toward solutions to the gun violence crisis.

CONTACT US

Additional Resources

In addition to the information above, the following tools provide additional resources to assist communities, policymakers, violence prevention advocates, and others.

This fillable PDF provides guidance to organizations and coalitions that are thinking about how to identify problems, necessary resources, and key stakeholders.

Communities that bring people together virtually or in person can use this resource to help stakeholders identify and document the current landscape and next steps.

This statewide resource guide, “How to Get Help When Someone May Hurt Themselves or Others” provides information on a variety of resources, ranging from contacting 911 to accessing social services, attorneys, courts, and others. It has been translated into Spanish and Mandarin and can serve as an example for other jurisdictions.

This landing page for Giffords Law Center’s implementation work provides links to many of the above resources, and is intended to serve as an overview of the “why” and the “how” of gun safety law implementation.

JOIN THE FIGHT

Over 40,000 Americans lose their lives to gun violence every year. In communities, courts, and ballot boxes nationwide, Giffords fights to save lives from gun violence. Will you join us?