Implementing the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act: One Year In

While the Biden administration has taken steps to ensure that the BSCA is as effective as possible, implementation of this historic law has only just begun.

Foreword By Senator Chris Murphy

Just a few weeks after I was elected to the Senate in late 2012, 20 children and six educators were murdered in Sandy Hook Elementary School by a disturbed young man wielding an assault weapon and high-capacity magazines—a tragedy that shocked the nation to its core. When I heard the news, I rushed to Newtown and was forever changed by the unspeakable things I witnessed that day. In the days and weeks that followed, I promised the parents and families of those killed that I would never stop fighting to fix our country’s broken gun laws that set the stage for their pain and grief.

I was sworn into the Senate just weeks later, and I immediately went to work to pass commonsense gun safety legislation to prevent this type of senseless slaughter from happening again. Our popular, bipartisan 2013 bill was filibustered by gun lobby allies just months after the tragedy. Some saw this defeat as the final word in the debate, but many of us refused to give in. We knew the modern gun safety movement was just beginning.

In the more than 10 years that followed, there have been thousands of mass shootings, more than 400,000 lives lost to gun violence, and more than one million people shot, injured, and living with trauma. For years, Congress was complicit in this daily slaughter by refusing to do anything to stop it.

El Paso. Atlanta. Boulder. Dayton. Parkland. Las Vegas. Pulse Nightclub. Sutherland Springs. Buffalo. Charleston. These communities, and so many more, have become synonymous with tragedy.

Beyond the mass shootings that captivate the media, communities of color suffer from daily gun violence and rarely receive attention from the media. Guns are now the number one cause of death for children and minors. It is unacceptable that so many families are destroyed by gun violence.

Adding to the frustration is the fact that we know the solutions to end this public health crisis. We know that we must strengthen gun laws at the federal level and in our states if we want to save lives from gun violence. We know we must invest in community-based, evidence-informed violence intervention strategies. We know we must separate people who intend to do harm from weapons that can end the lives of dozens in minutes.

When history repeated itself last year with 19 children and two adults murdered, and 17 more shot and injured, inside Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas, by a disturbed man wielding another assault weapon, the nation’s hearts were once again broken. I knew our government needed to do something, anything, and pleaded with my Senate colleagues to put aside their differences and pass legislation that would stop another horrific massacre from happening.

This time things were different.

Over the next few weeks, I led a group of four Senators—two Democrats and two Republicans—negotiated the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act (BSCA), the first major federal gun safety bill signed into law in nearly 30 years. This law represents Congress at its best, coming together to find compromise and impactful solutions to the challenges that we face as a nation.

The BSCA addresses some of the gaps in federal law concerning access to firearms—including improving background checks, addressing the deadly nexus of domestic violence and firearms, and preventing the easy flow of crime guns by making gun trafficking a federal crime—and also invests in community violence intervention programs, school-based violence prevention programs, and crisis intervention programs to remove firearms from people at greatest risk of violence.

I will be the first to tell you that the BSCA is not perfect, nor is it the one singular solution to end all gun violence. But it is an important and significant step forward, and it has made a real difference for public safety—as this report outlines in detail. As funding continues to flow and new restrictions keep dangerous guns out of dangerous hands, countless lives will be saved.

However, the work to end gun violence must continue. Gun violence, including mass shootings and school shootings, still plagues our country. The Biden administration should take additional steps to improve implementation of the law and ensure that as many lives are saved as possible. Congress must pass more gun safety legislation and strengthen federal gun laws.

As we mark one year since passage of the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act, let the lesson be that it is not only necessary to find bipartisan solutions to the challenges our nation faces, it is also very possible. It is possible to negotiate with colleagues across the aisle in good faith. It is possible to achieve compromise. It is possible to put aside politics and get things done for the people who send us to Washington DC to not only improve their lives, but also to save their lives.

CHRISTOPHER S. MURPHY

UNITED STATES SENATOR, CONNECTICUT

Introduction

On June 25, 2022, President Biden signed into law the first federal gun safety legislation in nearly 30 years. This historic, bipartisan accomplishment came on the heels of devastating mass shootings in Buffalo and Uvalde. But it wasn’t an overnight achievement: Its passage was the result of years of hard work by survivors and advocates around the country. While this legislation barely touched everything that gun safety advocates have been fighting for, it represented important change, as well as proof that progress is possible on this issue.

BSCA Implementation Report: Factsheet

While the Biden administration has taken a number of important steps to ensure that the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act (BSCA) is as effective and saves as many lives as possible, implementation work has only just begun. To commemorate the one year anniversary of this significant legislation, our experts conducted an analysis of ongoing implementation efforts around the BSCA. This report features our analysis of current progress, as well as recommendations for further comprehensive and equitable implementation of all the BSCA’s provisions.

As GIFFORDS has written previously, robust implementation of gun safety laws is critical to ensuring that policies and procedures are shared widely, understood sufficiently, and resourced appropriately. Implementation of the BSCA requires federal agencies to work closely with state and local agencies, a complicated endeavor that makes it even more important that the administration does everything in its power to clarify any outstanding questions and ensure consistent and thorough implementation across the board.

Our report highlights the status of implementation efforts related to the BSCA’s provisions, including:

- Enhanced background checks for individuals aged 18 to 20

- Funding for extreme risk protection orders through the Byrne State Crisis Intervention Program

- Funding for community violence intervention strategies

- Addressing the dating partner loophole

- Defining firearms trafficking

- Funding for school-based intervention and prevention programs

- Clarifying language around gun dealer licensing

This report provides a snapshot of the critical yet challenging work of implementing legislation after its passage. The more robust and thorough implementation efforts are, the more effective this legislation will be and the more lives will be saved.

GIFFORDS is grateful to the Biden administration for all of its work to ensure the success of the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act, and we look forward to working with the administration to implement the recommendations in this report.

MEDIA REQUESTS

Our experts can speak to the full spectrum of gun violence prevention issues. Have a question? Email us at media@giffords.org.

Contact

Implementation of BSCA Policies

From the moment the BSCA was signed into law in June 2022, the Biden administration and states began working together to take advantage of new funding streams, implement new gun safety measures, and strengthen existing laws. Below, we examine the implementation status of each provision of the BSCA.

Under 21 Background Checks

Young people disproportionately commit gun homicides: people aged 18 to 20 comprise just four percent of the US population, but account for 17% of known homicide offenders.1 Several recent mass shootings—including the tragedies in Buffalo, New York; Uvalde, Texas; Raleigh, North Carolina; and Dadeville, Alabama—involved perpetrators under the age of 21. Because of these shootings, Congress included within the BSCA a provision addressing the ease of access to firearms for people under age 21.2 As described below, the administration has begun conducting the enhanced background checks this provision enables for these gun buyers. Nevertheless, much more can be done to maximize the effectiveness of this provision.

Background

Young people are at elevated risk of engaging in violent behaviors against themselves or others. In addition to mass shootings and homicides, because impulse regulation and emotional control continues to develop into the mid-20s, young people, including adolescents and people under age 21, are at elevated risk of attempting suicide. Suicide risk is often much higher in the early stages of the onset of major psychiatric conditions, which usually first develop in adolescence or early adulthood.3 Suicide attempts that result in death or hospital treatment peak at age 16, but are at the highest rates from age 14 through age 21.4 Gun access can significantly increase these risks.

Source

Matthew Miller, Lisa Hepburn & Deborah Azrael, “Firearm Acquisition Without Background Checks,” Annals of Internal Medicine 166, no. 4 (2017): 233–239.

Prior to the enactment of the BSCA, a person under 21 who was purchasing a firearm from a federally licensed firearms dealer was treated like all other gun purchasers, regardless of their young age. Federal law allows licensed gun dealers to sell long guns (rifles and shotguns) to individuals who are 18 years of age or older, while they can only sell handguns to individuals who are at least 21 years of age.

Since the 1990s, federal law has required gun dealers to perform background checks on prospective firearms purchasers to ensure that the firearm transfer would not violate federal or state law. The National Instant Criminal Background Check System (NICS) was created to implement this background check requirement. The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), or state or local officials in a “point of contact” state, had three business days to complete the NICS check before the firearm could be transferred to the transferee. In other words, under the law as it existed before the BSCA was enacted, if the dealer was not notified within three business days that the sale would violate federal or state laws, the sale could proceed by default. This meant that a gun dealer could transfer a long gun (including a semiautomatic assault rifle) to an 18-year-old if their NICS check was not complete after three business days.

Enhanced Background Checks for Young People under the BSCA

Under the BSCA, prospective firearms purchasers between the ages 18 and 20 undergo expanded background checks. More specifically, the BSCA requires the NICS background check system to take the additional step of contacting state juvenile justice and mental health repositories and local law enforcement whenever a person under age 21 tries to buy a gun. If these repositories or local law enforcement then identify a potentially disqualifying record for the person within three business days, the system has up to 10 business days from the dealer’s first contact with the system to determine whether the person is disqualified from possessing a gun. The procedure in existence before the enactment of the BSCA, which allowed only three business days for the background check to be completed before a firearm could be transferred, remains in place for gun buyers who are age 21 or older, but the new procedure must now be used whenever a gun buyer is under age 21.

As discussed below, the Biden administration has taken substantial steps to implement this new provision, but there is more that needs to be done. Most importantly, the FBI—which houses the NICS used to vet gun purchasers—or the state or local officials in “point of contact” states must work closely with the federal, state, and local officials who conduct NICS checks to implement the enhanced background check procedures for buyers under the age of 21. And, as the regulatory agency for the gun industry, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) must ensure that gun dealers, importers, and manufacturers understand their responsibilities with regards to buyers under age 21.

Tougher Background Checks Are Working

The FBI began a phased implementation program in October 2022. According to a White House fact sheet, the Department of Justice (DOJ) has implemented expanded NICS background checks in the 43 jurisdictions for which the FBI processes background checks.5 Since November 2022, the FBI has conducted more than 89,000 expanded NICS background checks for firearm purchasers under age 21 and, as of June 14, 2023, has kept more than 200 firearms out of the hands of young people who should not have them solely because of the BSCA.6 Ten out of the 13 states that process their own background checks have fully implemented enhanced background checks, and the DOJ continues to provide technical assistance to the remaining three states.

According to the fact sheet, the DOJ is working with state and territorial governments and local law enforcement to increase their response rates to the NICS inquiries when someone under age 21 attempts to purchase a firearm. As a part of this, the DOJ has hosted 18 webinars, attended by more than 500 law enforcement agencies, with nine more webinars planned.

The administration also intends to partner with the DOJ to convene state and local law enforcement leaders to solicit their collaboration on increasing state and local law enforcement agencies’ response rates to enhanced background check inquiries when someone under age 21 attempts to purchase a firearm. In addition, the administration plans to work with state legislators and governors to urge them to enact laws allowing NICS to access all records that could prohibit someone under age 21 from purchasing a firearm.

Recommendations

While these are important steps, the administration has a long way to go to fully implement these enhanced background checks. As the administration continues to implement the BSCA, GIFFORDS recommends ATF:

- Issues new rules to update dealers’ responsibilities when a buyer is under age 21, including to wait 10 business days before transferring the gun if the dealer receives a notice about a potentially disqualifying record.

- Ensures that its inspectors are prepared to help enforce the law. ATF must ensure that industry operations investigators (IOIs) receive training regarding the BSCA’s provisions. In particular, IOIs must now ensure that gun dealers, importers, and manufacturers are not proceeding with sales to buyers who are under age 21, for whom a potentially disqualifying record has been found, before 10 business days have passed or the system has determined that the person is not disqualified. If a business willfully refuses to comply with this new law, ATF may revoke the business’s license.

- Helps gun dealers, importers, and manufacturers understand how the new law works in conjunction with state firearms laws. Many states have their own laws regarding abusive dating partners, gun buyers under the age of 21, employee background checks, and stolen firearms. ATF should conduct a separate analysis for each state and inform gun businesses in that state about the laws that apply there.

GIFFORDS also recommends the FBI:

- Issues new rules for NICS regarding background checks for people under age 21. The FBI’s regulations regarding NICS delineate the databases that are searched when a licensed gun dealer, importer, or manufacturer contacts the system to conduct a background check on a gun purchaser. These regulations will have to be amended to ensure that additional steps are completed for buyers under age 21.

GET THE FACTS

Gun violence is a complex problem, and while there’s no one-size-fits-all solution, we must act. Our reports bring you the latest cutting-edge research and analysis about strategies to end our country’s gun violence crisis at every level.

Learn More

Crisis Intervention

A critical piece of the BSCA created a new grant to support states in creating and administering state crisis intervention court proceedings and related programs or initiatives, particularly “extreme risk protection order” programs, and including, but not limited to, mental health courts, drug courts, and veterans treatment courts. The BSCA itself appropriated $750 million across Fiscal Years 2022 through 2026 in dedicated funding for this new grant.7 As described below, states have promised to use this funding to support a variety of programs. In utilizing this funding, GIFFORDS recommends focusing on the key question of access to firearms.

Background

Extreme risk protection order (ERPO) laws allow law enforcement officers and other key members of the community to petition the courts for a civil order which would temporarily suspend firearm access for people at demonstrated risk of harming themselves or others. This new grant program would fund state efforts to implement ERPO laws, but may also bolster the efforts of mental health courts, drug courts, and veterans courts in ensuring individuals who pose a threat are not able to access firearms while in crisis.

Following the enactment of the BSCA, the Department of Justice’s Office of Justice Programs (OJP) established a grant program called the Byrne State Crisis Intervention Program (Byrne SCIP). This program is now administered by the Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA). The DOJ released the first solicitation for the new grant program, accounting for Fiscal Year 2022 and 2023 for the first allocation of funding in December 2022.8

Byrne SCIP is a formula grant, which means that every state and US territory is allocated funding according to the formula used by the Edward Byrne Memorial Justice Assistance Grant (Byrne JAG) program, which is based on the state’s population and number of reported violent crimes. However, states must still apply for this funding when the solicitations are open via a state-designated State Administering Agency, and they may only submit one application per solicitation. State agencies are allowed to retain 60% of the awarded funding, with 40% of the funding being “passed through” to local governments, including cities, counties, townships, or certain tribal entities. Funding could also be passed through to local prosecutors’ offices, public defenders’ offices, public health agencies, court systems, and law enforcement agencies.

According to the solicitation, states must establish a Crisis Intervention Advisory Board to support how the state uses the federally provided funding to implement crisis intervention programs. This board must be diverse, including representatives from law enforcement, courts, behavioral health providers, and victim services. States must use information provided by the Crisis Intervention Advisory Board to determine how the funding is passed through to specific local units of government.

Forty-six states, four US territories, and Washington DC applied for and were awarded funding under this program. In total, $241 million was awarded across these 51 jurisdictions, with amounts varying based on the allocation formula. Four states—Florida, South Dakota, Wyoming, and Mississippi—did not apply for and were subsequently not awarded Byrne SCIP funding for FY22-FY23,9 despite the fact that gun death rates in many of these states are among the highest in the nation.10

While most states have accepted these awards and begun implementing the proposed plans, Virginia has not yet accepted the award.11 The state is in the process of finalizing its budget for the fiscal year, which, based on what is known as of the publication of this report, is believed to be the reason for not accepting the funding.

State Funding Plans under the BSCA

To better understand how states plan to use this money to prevent gun violence, GIFFORDS reviewed the proposal narratives from applications submitted by the 46 states which applied for funding and Washington DC. In order to apply for funding, each state had to submit a proposed project description for the specific work the funding would support.

As described below, most states proposed work across a variety of areas, with plans to use funding to implement or support a number of policies, programs, and services. Six states provided almost no specific details about their plans to use the funding, indicating that their plans would be defined after the creation of a state advisory board. These states were included in the analysis, but as their plans solidify, the proportion of states using the funding for particular work may shift.

Proposals to Support Specialized Court Systems and Related Programs

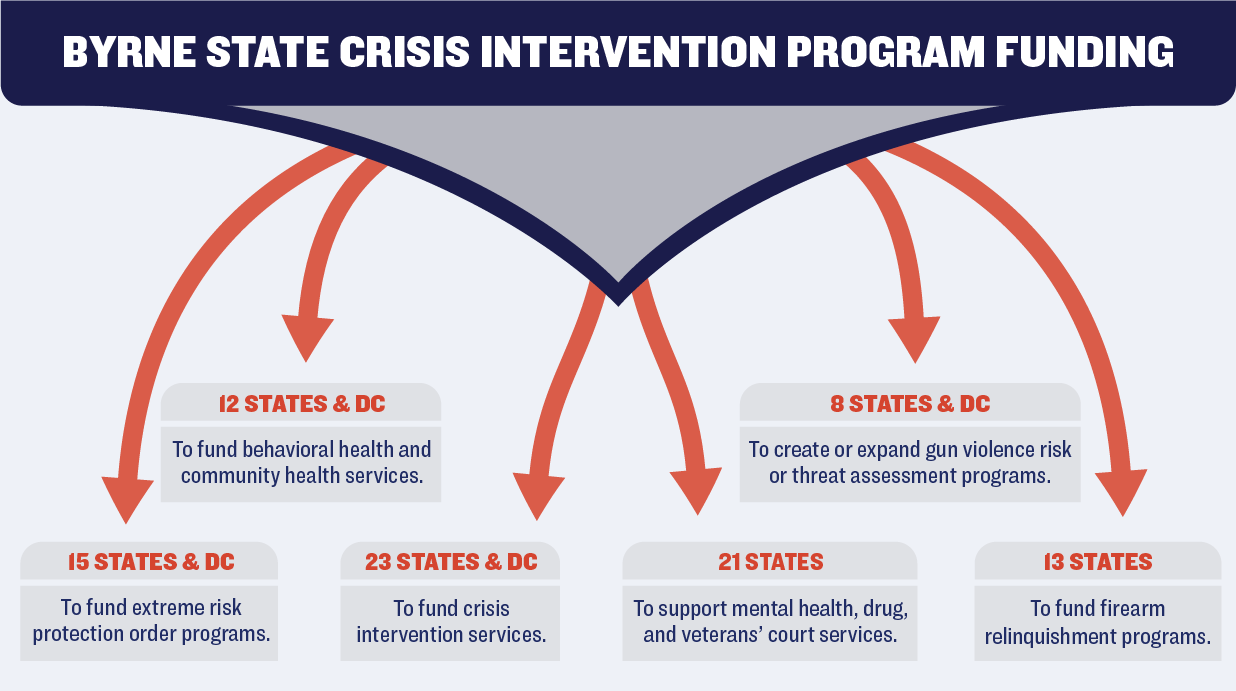

The most commonly proposed plan was to use this funding to improve behavioral health and community health services. Twelve states and DC designated plans to better fund these services, either broadly within the community or for specific groups of people, such as those involved in the court system. Twenty-three states and DC similarly proposed using this money to fund crisis intervention services, including co-responder models and training for law enforcement regarding intervention with people in mental health crises.

Twenty-one states expressed plans to use this funding to support specialty court services, including mental health, drug, and veterans courts. Many of the proposals specifically indicated that they would expand opportunities for these courts to assist clients who are most likely to commit or become victims of gun crimes. Relatedly, at least eight states and DC also proposed creating or expanding gun violence risk assessment programs or threat assessment programs, which would create and train key stakeholders to assess the credibility and seriousness of potential gun violence threats. States proposed implementing these programs in a variety of settings, including within courts and police departments.

Thirteen states proposed using funding to safely secure, store, track, and return firearms that are relinquished because of court orders and other prohibiting events. Anecdotal evidence suggests that many police departments struggle to store guns seized from people prohibited from having them.12 Thus, these programs may in part facilitate better implementation of firearm relinquishment orders, including ERPOs, domestic violence protection orders, and other kinds of civil and criminal court protective orders that disarm individuals at demonstrated risk of violence. Four states which included this proposed use of funding in their project descriptions already have extreme risk protection laws.

Proposals to Support the Adoption or Implementation of Extreme Risk Protection Order Laws

Sixteen states proposed using funding to support the adoption or implementation of ERPOs.13 Thirteen of these states have extreme risk laws. Three states—Arkansas, Arizona, and West Virginia—do not yet have extreme risk laws yet suggested that funding would be used to support extreme risk law adoption.

Although these numbers are promising, they also show significant opportunity for more states to use this funding to implement extreme risk laws. In fact, there were six states and DC which have extreme risk laws but did not propose to use funding to support the implementation and use of these orders. Twenty-four states without extreme risk laws submitted proposals that did not include using this funding to support the adoption of these laws. Even more concerningly, three of these states—Idaho, Montana, and Wisconsin—explicitly noted in their proposals that funding would not be used to support the adoption of extreme risk laws.

It is also important to note that two states referenced ERPO implementation as a component of better implementation of other kinds of civil and criminal court protective orders that can promote safety and disarm individuals at highest risk of violence. Plans that implement these various orders holistically are critical for ensuring that the correct orders are used in the correct circumstances. For example, in addition to its extreme risk law, California law offers processes for domestic violence, workplace violence, postsecondary school violence, elder abuse, and civil harassment restraining orders that disqualify the respondent from accessing weapons in addition to other broader safety protections. The California SCIP proposal indicated that funding would be used to develop model procedures that will assist courts in facilitating different kinds of firearm relinquishment orders. Washington similarly referenced using funding to implement various protection order laws.

Potential Funding Uses Not Driven by the Courts

A number of states also proposed plans to use SCIP funding to support other violence prevention programs and work not driven by court proceedings. For example, at least nine states explicitly indicated that funding would be used to provide and implement new law enforcement trainings and technologies. Michigan, for instance, proposed funding ballistic identification technology projects with law enforcement, prosecutor, healthcare, behavioral health, and community partners. Nebraska proposed using funding to support the state’s use of the National Incident Based Reporting System (NIBRS)—which has recently become the primary federal program for collecting crime data—and to integrate these crime data collection efforts with other case management and reporting systems.

Six states proposed using funding to support safe storage programs. The state of Utah, for example, proposed increasing safe firearm storage options by providing free portable biometric safes and creating a publicly accessible map of gun dealers and shooting ranges that support temporary out of home storage options.

Of note, three states—Georgia, Massachusetts, and Tennessee—listed community violence intervention programs as a potential use of this funding. Texas specifically noted that funding might be used to support reentry programs, which may provide an opportunity to reach and provide services to a group at particularly high risk of gun violence victimization and perpetration.

Recommendations

Our review of the proposed SCIP projects suggests that states have clear plans to use these funds effectively and on initiatives that specifically aim to prevent firearm violence. However, as states begin spending this funding and propose new projects in the coming years, the following recommendations should be kept in mind.

More states should ensure that this funding is used, in part, to support complete and robust implementation of ERPO laws. More specifically:

- There are many states without extreme risk laws that should use this funding to support the passage of these laws, including but not limited to engaging potential implementation stakeholders, building community awareness of this tool, and ensuring that courts and law enforcement agencies have the proper capacity to implement this tool should it become available.

- Additionally, there are many states that have passed ERPO laws but did not indicate that they would use funding to support ERPO implementation. These states should consider this use of this funding in the future.

For the states which have proposed using this funding to support the implementation of state-level ERPO laws, we recommend using this funding to:

- Expand knowledge among key implementation stakeholders, including members of the community, about the availability of ERPOs as a means to temporarily suspend access to firearms when someone poses a credible danger to themselves or others.

- Train a variety of stakeholders, including law enforcement, judges, lawyers, and public defenders to promote understanding of how these orders can be used to prevent gun violence, and ensure that they can effectively assess and engage with a person experiencing a crisis.

- Train law enforcement officers who serve ERPOs, particularly on how to engage with an individual in suicidal crisis and de-escalate these situations.

Finally, all awardees should engage regularly with the technical assistance advisors, as designated by the DOJ, including on how they set up their Crisis Intervention Advisory Boards as well as on decision criteria related to what programs and units of government receive funding from the overall grant.

CONVERSATIONS WITH EXPERTS

Giffords Center for Violence Intervention’s webinars explore different aspects of community violence through conversations with experts.

WATCH NOW

Community Violence Intervention

Community violence, which includes homicides, shootings, stabbings, and physical assaults between unrelated individuals outside the home, is devastating communities and disproportionately impacting Black and Latino residents. Particular intervention strategies, known collectively as community violence intervention (CVI), are highly effective at reducing this form of gun violence. For that reason, the BSCA appropriated $250 million for grants to fund these strategies.14 As described below, the DOJ is not only using this funding to support effective programs that promise significant reductions in community violence, but is also ensuring that newer programs can grow through an emphasis on exchange of expertise among different programs across the country.

Background

In 2021, nearly 21,000 lives were taken by homicide—81% of which were committed with firearms—and tens of thousands more were injured severely enough to require hospitalization. Although Black and Latino residents make up less than a third of the US population, these groups account for more than three-quarters of gun homicide victims in the US. These disparities are further exacerbated by a historical lack of investment, which puts communities of color in a position where they are far too under-resourced to address the magnitude of these issues without a concerted attempt to support their efforts. However, leveraging community violence intervention approaches has shown to be a worthy investment.

Community violence intervention refers to a set of non-punitive, community-led strategies that are designed to interrupt the transmission of violence by engaging those at highest risk through the provision of individually tailored support services. These interventions work to mitigate the effects of violence on individuals and communities by providing support, resources, and pathways to healing.

This type of work can take place in a variety of settings, including hospitals, community centers, and neighborhood blocks. Examples of CVI programs include hospital-based violence intervention programs, street outreach and violence interruption initiatives, and case management and mentoring opportunities—all of which have been shown to be effective in reducing violence and breaking the cycle of violent injury in many communities across the country.

Funding the New Community-Based Violence Intervention and Prevention Initiative at DOJ

Historically, the federal government has not provided adequate funding to support violence prevention, with even fewer resources available for community-led interventions. In the past few years, however, the Biden administration has taken meaningful action to direct more federal dollars to community violence intervention programs and strategies.

Beginning with the passage of the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2022, which provides the federal government’s budget for Fiscal Year 2022, Congress allocated $50 million to establish the Community-Based Violence Intervention and Prevention Initiative (CVIPI) within the Department of Justice’s Office of Justice Programs (OJP).15

BLACK AMERICANS ARE AT HIGHER RISK OF GUN HOMICIDE

Source

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (WONDER), “Underlying Cause of Death, 2018-2022, Single Race,” last accessed May 1, 2024, https://wonder.cdc.gov/.

CVIPI is a first-of-its-kind grant program dedicated to supporting the development, implementation, and expansion of CVI programs and strategies, with an emphasis on communities experiencing the highest rates of violence.

With the passage of the BSCA, CVIPI received an additional $250 million investment over five years. This doubled CVIPI’s budget in Fiscal Year 2022, allowing for the DOJ to award a total of $100 million to 53 cities and nonprofits in support of violence intervention and prevention in September 2022. This funding includes technical assistance to grantees, an award for the development of a resource and field support center, and four awards to intermediary organizations that will work with small community-based organizations (CBOs) to pass through funds and help build their capacity.

Additional funding provided by the BSCA will be administered to a second cohort following a request for proposal (RFP) process which concluded on May 18, 2023. This second round of funding will provide an estimated $72 million to between 31 and 38 cities, states, intermediaries, and CBOs.16 Furthermore, a separate RFP process is making available approximately $15 million for research, evaluation, training, and technical assistance (TTA).17 These awards are intended to provide TTA to support the evaluation of CVIPI and conduct violent crime problem analyses, site-based evaluations, and other community violence–related research.

While this funding level falls short of the $5 billion investment in CVI previously called for by the Biden administration,18 CVIPI marks significant progress toward resourcing and recognizing the importance of violence intervention work.

Measuring Success in CVI Programs

As the field of community violence intervention continues to develop, it is essential to establish metrics of success that are realistic and meaningful. This is vital to ensure that programs and initiatives are held accountable and can prove their effectiveness in reducing gun violence and enhancing community safety.

At the same time, there are internal metrics of success that are equally important. One such measure of success is securing a federal grant in and of itself. Historically, smaller organizations have struggled to compete for federal funding due to the complex application process and stringent requirements. Therefore, successfully securing a grant not only provides financial support but also demonstrates expertise and credibility in the field that can help increase accessibility to additional funding opportunities and partnerships in the future.

During the application process for CVIPI, grantees were required to identify specific metrics of success that were relevant to their programs. A majority of the funded programs in the first cohort shared common metrics of success, such as an increase in the number of individuals served, a reduction in violent crime, and greater access to mental health services.

Several grantees seek to strengthen community partnerships, decrease recidivism, and increase engagement with the community. Others hope to demonstrate success through increased employment opportunities, higher high school graduation rates, enrollment in higher education, and increased opportunities for youth mentorship among their participants. These shared metrics of success demonstrate the common goals and priorities among the funded programs, providing valuable insight into our understanding of the expected outcomes of these federal investments.

Programs funded under CVIPI include:

- Metropolitan Family Services (Chicago, Illinois) is leveraging CVIPI funds to expand the Metropolitan Peace Academy’s training programs for outreach workers and provide front-line staff with social-emotional and wellness support for those experiencing high exposure to trauma.

- Newark Community Street Team Inc. (Newark, New Jersey) hopes to use CVIPI to expand its High Risk Interventionist program by hiring and training additional staff, hosting bi-weekly public safety forums, providing case management, developing a citywide violence reduction strategy, and participating in research and evaluations.

- Greensborough, North Carolina, is expanding its Office of Community Engagement to expand the violence intervention and prevention services offered by partners and introduce new programming as well. This initiative will focus on identifying high-risk individuals and connecting them with partner organizations for services, while also aiming to improve relationships between community and law enforcement and addressing systemic issues such as food and housing insecurity, unemployment, and access to healthcare and education.

- In Harris County, Texas, where the City of Houston is located, the Public Health Department’s Community Health and Violence Prevention Services aims to provide wraparound services to high-risk individuals through the county’s ACCESS Harris program. Through ACCESS Harris, the county hopes to develop dedicated resources and strategic personalized interventions designed to address the root causes of violence.

- Kansas City, Missouri, is leveraging this grant to expand its CVIPI Neighborhood Outreach Team within the Health Department’s Aim4Peace Program. The city’s CVIPI award will enable Aim4Peace to expand services to additional neighborhoods and broaden the reach of the program.

As the projects above suggest, organizations are prepared to make the most of this new funding opportunity. CVIPI stands to provide critical resources and support to a number of promising initiatives all across the US.

Recommendations

Allocating more funds towards community violence prevention and intervention can have a significant impact in curbing violence and ensuring community safety. As such, GIFFORDS strongly prioritizes continued support and expanded funding for community violence intervention as part of a comprehensive strategy to reduce violence across the country. However, it is also crucial to ensure that these funds reach the hands of those who are actively engaged in the work.

Providing additional funding support to intermediaries is an essential part of expanding access to these resources. One function of these organizations is to act as a pass-through agency for community-based organizations lacking sufficient capacity to manage a federal grant. With increased funding, intermediaries are better positioned to assist small CBOs, allowing them to maximize the impact of their violence prevention efforts within their communities.

To enhance the effectiveness of community violence intervention efforts, it is critical to stay attuned to the prevalent challenges faced by organizations in need of robust support. One way to achieve this is by surveying CVIPI applicants to gain insights into the specific challenges they encounter and actively seeking feedback to better understand their needs and tailor federal support accordingly, similar to the convening held for CVIPI grantees held in St. Louis earlier this year. By continuing to dedicate a focused effort to learning and understanding the needs of community organizations, the federal government would be in a prime position to establish an Office of Community Violence Intervention. This office could provide carefully curated support for the field and effectively coordinate efforts across multiple agencies and ultimately shape the foundation for the field of community violence intervention.

2024 CVI CONFERENCE

Giffords Center for Violence Intervention will host the 2024 Community Violence Intervention Conference in Los Angeles on June 24 & 25.

Learn More

Intimate Partner Violence

The dangerous nexus between domestic or intimate partner violence and firearms is well documented. A gun in the hands of someone who commits domestic abuse makes a woman five times more likely to be killed.19 As a result, the BSCA addressed a key gap in federal law that leaves victims of abuse vulnerable to injury and death by an armed domestic abuser. As detailed below, the Department of Justice has taken certain steps to implement this provision, but more remains to be done to fully protect victims. Most importantly, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) must issue a regulation that clearly defines the scope of this provision, so gun sellers, gun buyers, law enforcement, courts, and other members of the public can fully recognize whether a particular violent individual who commits abuse is legally eligible to purchase and possess firearms.

Background

Every 16 hours, a woman is shot and killed by a current or former intimate partner in the US, and women in the US are 21 times more likely to be killed with a gun than women in other high-income countries. Armed abusers also use guns to terrorize, control, threaten their victims, families, and children. An abuser’s access to a gun also creates a danger that extends beyond the family, into the community and even to mass shootings. In more than half of mass shootings where four or more people were killed, the shooter killed an intimate partner.20 One analysis found that nearly one-third of mass shooters had a history of domestic violence.21

Domestic Violence

The combination of intimate partner violence and access to guns is an especially deadly mix.

Until recently, federal law only prohibited gun purchase and possession among intimate partners convicted of misdemeanor domestic violence if the abuser shared a narrowly defined relationship with the victim, which excluded dating partners. However, more than half of all intimate partner homicides are committed by dating partners. Closing this deadly loophole, often referred to as the dating partner loophole, is vital to protecting survivors of domestic violence—states that prevent abusive dating partners from owning guns have 16% fewer intimate partner gun homicides.22

New Provision under the BSCA for Dating Partners

The federal law prohibiting people convicted of certain domestic violence crimes from buying or owning guns was adopted in 1996, as an amendment to the Gun Control Act of 1968. This amendment, commonly known as the “Lautenberg Amendment” after its sponsor, the late Senator Frank Lautenberg (D-NJ), defines a “misdemeanor crime of domestic violence” as an offense that is a federal, state, or tribal law misdemeanor and has the use or attempted use of physical force or threatened use of a deadly weapon as an element. In addition, the offender had to fit one of the following criteria to be prohibited from purchasing or possessing firearms:

- Be a current or former spouse, parent, or guardian of the victim

- Share a child in common with the victim

- Be a current or former cohabitant with the victim as a spouse, parent, or guardian

- Be similarly situated to a spouse, parent, or guardian of the victim

The BSCA expands the Lautenberg Amendment by adding a category of individuals to partially close the dating partner loophole. Specifically, the BSCA prohibits gun purchases and possession for five years by an individual convicted of a misdemeanor crime of domestic violence against a victim with whom they have or had a “current or recent former dating relationship.”23 The BSCA defines a “dating relationship” as “a relationship between individuals who have or have recently had a continuing serious relationship of a romantic or intimate nature.” A dating relationship is determined based on the consideration of “(i) the length of the relationship; (ii) the nature of the relationship; and (iii) the frequency and type of interaction between the individuals involved in the relationship.” A dating relationship does not include “a casual acquaintanceship or ordinary fraternization in a business or social context.”

New Forms and Training

The FBI took steps to implement the new prohibition for those convicted of violence in a “dating relationship” in August 2022.24 In December 2022, ATF published its updated Form 4473 Firearms Transaction Record to address the new prohibitor. Specifically, the form notes when an individual convicted of a misdemeanor crime of domestic violence is no longer prohibited25 and updates the definition of misdemeanor crime of domestic violence to include dating relationships.

Additionally, prosecutors and ATF agents received initial training on the new definition, and there are ongoing efforts to educate local law enforcement and prosecutors of the need to document “dating relationship” factors in police reports and court records.26 In May 2023, the Biden administration announced its intention to convene state and local law enforcement leaders to solicit their collaboration on BSCA implementation priorities, including ensuring that arrest and adjudication records include additional documentation of dating relationships.27 If the relationship is not documented, the background check system used for gun purchases will not be able to deny the person a firearm.

Recommendations

While these are important steps, the Biden administration has a long way to go to fully implement this new provision. As the administration continues to implement the BSCA, GIFFORDS recommends that federal, state, local, tribal, and territorial agencies work together to ensure this prohibitor is better understood by all stakeholders.

- Gun dealers, importers, and manufacturers must understand how the new law works in conjunction with state firearms laws. Many states have their own laws regarding abusive dating partners, gun buyers under the age of 21, employee background checks, and stolen firearms. ATF should conduct a separate analysis for each state and inform gun businesses in that state about the laws that apply there.

- State and local law enforcement, as well as courts, need to be educated on documenting relationships between the victim and the abuser on forms and in other records to ensure those who are a risk to themselves or another are prevented from purchasing or possessing firearms. Notably, when the Department of Justice recently released its annual solicitation for applications for federal funding for state efforts to improve reporting to the background check system, it neglected to acknowledge the new work that states and local governments must do to implement the new prohibition for abusive dating partners.28

- State and local law enforcement should be trained on firearm relinquishment so that individuals prohibited from possessing firearms do not have access to their firearms for the length of the prohibition.

- The public should also receive targeted information on the new prohibitor so that they are aware of who should and should not have access to firearms, and do not mistakenly transfer a firearm to an individual who is prohibited from possessing firearms.

- Agencies should work together to develop new policies and practices and train the federal, state, and local officials who operate NICS to properly evaluate criminal history records that involve misdemeanor convictions for dating partner violence.

More importantly, however, ATF should issue new rules that clarify the definition of “dating relationship” and distinguish this group from individuals convicted of domestic violence misdemeanors against those “similarly situated to a spouse.” A formal regulation of this type is necessary to provide law enforcement and the courts a framework for identifying whether particular individuals should be reported to the background check system used for gun purchasers, as well as whether they can be prosecuted if found to be in possession of a firearm.

In elucidating the term “dating relationship,” ATF should ensure that this new prohibition for abusive dating partners encompasses dating relationships as represented by the lived experiences of survivors of dating violence, as described by advocates for those survivors. Dating partner violence may continue long after a survivor says the relationship is over because the perpetrator is unable to accept the end of the relationship. ATF’s new rule should recognize the seriousness of such a relationship, and the danger posed by a gun in the hands of the perpetrator. For these reasons, we urge ATF to take into account the nature of the relationship in its cultural context and not to rely too heavily on numerical requirements for the relationship.

STAND UP FOR SAFETY

Americans are not as divided as it may seem. Join Giffords Gun Owners for Safety to stand in support of responsible gun ownership. We’ll share ways to connect with fellow gun owners and support our fight for a safer America.

Gun Trafficking

Gun trafficking and straw purchasing have been fueling America’s gun violence crisis for decades, and the lack of strong federal laws that address these crimes has undermined efforts to combat them. But with the passage of the BSCA came much needed provisions to combat gun trafficking and straw purchasing. These provisions have been used to charge more than 100 defendants and seize hundreds of firearms since the law was enacted.29 Yet, as described below, our analysis indicates that these new laws have yet to be widely implemented and used, in part because of a lack of resources within ATF.

Background

Due to inconsistent firearm regulation that varies widely from state to state, guns move far too easily from states with weak gun laws into states with strong gun laws. Gun trafficking and straw purchasing undermine important state and federal gun laws, with studies showing that trafficked guns are a major driver of crime, including gun homicides, in states with strong gun laws.

The prevalence of gun trafficking in the US is often measured by how many guns cross state lines before they are used in crime, which can indicate that guns were purchased in a state with weak gun laws and brought into a state with strong gun laws. In addition, a measure known as the time-to-crime indicates how long it takes for a legally sold firearm to end up used in crime. Firearms with a short time-to-crime are disproportionately associated with firearm trafficking.

Alarmingly, both of these measures suggest that firearm trafficking is a serious and growing problem. From 2017 to 2021, approximately one-third of traced crime guns were used outside the original state of sale,30 and nearly 46% of all traced crime guns over this period were recovered less than three years after their purchase.31

Research suggests that straw purchasing—in which a purchaser is actually buying a gun on behalf of someone else—is the most common channel identified in trafficking investigations.32 Data from a national survey of firearm licensees suggests that there are more than 30,000 attempted straw purchases each year.33

Despite the alarming scope of gun trafficking and straw purchasing, federal law lacked a clear and effective prohibition against either prior to the BSCA.

New BSCA Provisions to Define and Penalize Gun Trafficking

The BSCA establishes federal statutes to clearly define and penalize firearms trafficking and straw purchasing.34 It makes it unlawful for any person to “ship, transport, transfer, cause to be transported, or otherwise dispose of any firearm to another person… if such person knows or has reasonable cause to believe that the use, carrying, or possession of a firearm by the recipient would constitute a felony” or to “receive from another person any firearm… if the recipient knows or has reasonable cause to believe that such receipt would constitute a felony.” The maximum prison sentence under this provision is 15 years.

The BSCA also makes it unlawful for any person to “knowingly purchase, or conspire to purchase, any firearm… for, on behalf of, or at the request or demand of any other person, knowing or having reasonable cause to believe that such other person” is prohibited under federal law from possessing a firearm. The maximum prison sentence under this provision is 15 years.

In addition, the BSCA includes a number of other provisions aimed at various forms of gun trafficking, including smuggling guns from the US across the border to other countries, and allows law enforcement to seek the forfeiture of proceeds or property derived from, or used or intended to be used for, straw purchasing or gun trafficking.

Research suggests that these statutes may increase enforcement of these often overlooked crimes, which may lead to a reduction in gun violence. For example, one study found that when Pennsylvania clarified its straw purchase law to more clearly define violations, prosecutions for these offenses increased.35

These statutes also have the potential, if properly and equitably implemented, to focus law enforcement efforts on individuals responsible for supplying vast quantities of firearms in the illegal market, rather than on less serious offenders. For example, three out of four federal weapons prosecutions are for simple illegal gun possession.36 These laws could help disrupt the channels that fuel the illegal market, versus focusing just on people who purchase from that market.

Case File Review

To better understand the dynamics of these cases, GIFFORDS reviewed indictments and case files for cases charged under the new gun trafficking and straw purchasing statutes. Our review identified at least 18 cases filed between August 2, 2022, and February 10, 2023, charging 35 defendants with offenses under the new statutes.

Cases were brought in at least 12 states. Most of the cases involved individuals charged with gun trafficking. Just three defendants were charged with straw purchasing. As of May 1, 2023, 10 defendants have pleaded guilty to the charges.

ATF agents were involved in most of the investigations and arrests in these cases. However, many of these cases stemmed from investigations into other crimes or were brought to ATF’s attention by other federal or local law enforcement agencies later in the process. For example, one case where four individuals had trafficked approximately 10 guns per week into Mexico for at least four months was brought to ATF by the Drug Enforcement Agency as part of an investigation on drug trafficking. Another investigation was initiated by ATF after the local sheriff’s department reported an individual acquiring a large quantity of firearms. Ten of the 18 cases involved concurrent drug-related charges.

In many cases firearms were trafficked from states with weaker laws to states with stronger laws. For example, two separate cases involved firearms trafficked into New York, in one case from Ohio and in the other from Virginia. There were also five cases where individuals trafficked or intended to traffic firearms to Mexico from Texas. Many of the cases involved the sale of assault weapons and firearms with high-capacity magazines. Two of the 18 cases involved trafficking of machine gun conversion kits.

Additionally, this law was used to intervene in a number of cases where individuals trafficked or intended to traffic personally made firearms, also known as “ghost guns.” At least four of the 18 identified cases involved individuals who were selling or planning to sell ghost guns. In one case, for example, four defendants were charged with gun trafficking or conspiracy to commit gun trafficking for bringing ghost guns and guns from other states into New Jersey, which has some of the strongest gun laws in the nation.

A number of these cases involve a high volume of guns trafficked by or in the possession of alleged traffickers. One case, for instance, involved a defendant who purchased 231 firearms. Many of these firearms were trafficked into Mexico.37 In another case, two defendants trafficked more than 50 firearms from Ohio to New York.

In many cases, the firearms were fueling crime and gun violence.

- Firearms trafficked by four individuals from Virginia to New York were linked to multiple shootings in Brooklyn. One gun was used in an August 2021 shooting during which armed protesters shot into a large crowd gathered at a party and injured eight people by gunfire.

- Another individual charged with firearm trafficking acquired at least 46 handguns between April 2020 and August 2020 through multiple sale transactions. Beginning in November 2020, law enforcement began to recover these firearms at crime scenes. While the majority of these recoveries occurred in North Carolina, where the guns were originally purchased, there were also recoveries in other states, including seven firearms recovered in Pennsylvania, one recovered in Virginia, and one recovered in Florida. In total, 27 of these 46 firearms were recovered and traced by law enforcement in connection with other crimes.

- In another case, an individual purchased multiple firearms on behalf of her boyfriend, who was prohibited as a result of a felony conviction. One of these firearms was later used in a Lincoln, Nebraska, shooting.

Recommendations

Our review of these cases to date suggests that these new statutes can play an important role in disrupting the primary streams through which firearms enter the illegal market and are used in crime both domestically and abroad. Historically, the people who have been prosecuted by the federal government for firearms offenses have disproportionately been people who are the most proximate causes of gun crime and violence, rather than the upstream individuals who have created the circumstances for these other individuals to easily access firearms. The mismatch between historic enforcement efforts and the true drivers of gun violence have contributed to the many significant racial disparities in the criminal legal system. Thus, it is critical that equity is at every step of the process of implementing these new statutes.

In April 2023, the US Sentencing Commission released its Final Amendments to the Sentencing Guidelines for these new statutes. The amendments are aimed at ensuring that penalties for violations of these offenses do not have unduly negative effects on the less culpable individuals prosecuted, such as individuals who have straw purchased firearms due to coercion. The amendments would also recognize the seriousness of higher-volume, more sophisticated trafficking operations. Additionally, these amendments could help defray the potential for the new statutes to disproportionately affect people of color and other marginalized groups. The proposed amendments include:

- An amendment that specifies a downward sentence score adjustment for straw purchasers, provided that they did not have a significant criminal history and were motivated by intimate or familial relationships or by threats or fear to commit the offense, or were unusually vulnerable to being persuaded or induced to commit the offense due to physical or mental condition.

- An amendment specifying that a person convicted of these new crimes who is affiliated with a gang, cartel, organized crime ring, or other such enterprise is subject to higher penalties than an otherwise unaffiliated individual. The commission also created specific parameters to define “gang-affiliated” individuals.

- An amendment specifying sentence enhancements for individuals convicted of trafficking two or more guns.

These amendments have the potential to both minimize the disproportionate burden of these laws on communities of color and other marginalized groups, as well as focus enforcement on individuals most responsible for creating the conditions that allow gun violence to flourish. The Amendments are subject to congressional review. If Congress does not act, the amendments will become final on November 1.

Additionally, our case file review suggests the need to ensure that ATF is properly resourced to investigate gun trafficking channels. Although it is crucial that all law enforcement officials are aware of these new tools and are proactively working with ATF to identify cases where these statutes may be relevant, it is important that these charges are not merely used as “add-ons” to existing drug cases. Gun trafficking, particularly when it involves large quantities of firearms, is in and of itself a serious crime. As the federal agency charged with overseeing the gun industry and tracing crime guns, ATF has unique insight into sources and patterns of gun trafficking. It is critical that ATF is properly positioned to proactively identify and investigate gun trafficking channels and engage in targeted enforcement actions.

TAKE ACTION

The gun safety movement is on the march: Americans from different background are united in standing up for safer schools and communities. Join us to make your voice heard and power our next wave of victories.

GET INVOLVED

School-Based Intervention and Prevention Programs

America’s schools have an important role to play in keeping our students safe. They offer a critical touch point for reaching young people at risk of gun violence, and by providing students a pathway to future success, education serves as one of the best protective factors against future violence involvement. Moreover, school-based intervention and prevention programs that are evidence-informed and provide resources that help students cope with trauma can have a significant impact on safety for vulnerable young people.

Since schools can play such an important role in keeping kids safe, the BSCA appropriated more than $2 billion to advance school-based efforts to reduce gun violence. As described below, the Department of Education has taken a number of important steps towards ensuring this funding is used in a manner that will reduce gun violence for years to come.

Background

In 2020, for the first time in modern history, the leading cause of death for American children and teens was firearms.38 The lethality of firearm violence among school-aged children had steadily increased throughout the preceding decade—rising from 3.5 deaths by firearm per 100,000 children and adolescents in 2010 to 5.5 deaths per 100,000 children and adolescents in 2020. Since 2000, more than 150,000 Americans under the age of 18 have been killed or injured by a firearm.

Source

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS), “Leading Cause of Death Visualization Tool,” last accessed May 2, 2024, https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html. Calculations include children ages 1–17 and were based on the most recently available data: 2022.

This violence is concentrated in under-resourced communities and harms Black and Latino youth at a disproportionate rate. Black youth experience gun-related injuries at a rate that is 10 times higher than their white peers.39 In addition, among schools where demographic data were available, 64% of school shootings between 2013 and 2019 occurred at schools where more than 50% of the student population identified as a student of color.40

This violence takes a heavy toll on children’s mental and physical health, as well as their ability to perform academically—and disengagement from school and lack of educational resources are often precursors to an increased risk of violence involvement.41 This link between school disengagement and gun violence involvement is partially why Chicago saw a spike in shootings during the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2020, as Chicago Public Schools closed and the school district’s enrollment dropped by 16,000 students,42 youth shooting victimization in Chicago rose by 55%.43 But evidence shows quality education and healthy relationships between students, teachers, and counselors can serve as protective factors for youth and reduce the risk of dropout and violence involvement.44

Historic Funding For Schools under the BSCA

The BSCA appropriated more than $2 billion to advance school-based efforts to reduce gun violence.45 It appropriated $1 billion to expand “Student Support and Academic Enrichment Grants,” funding that will remain available for use by state and local education agencies through September 30, 2026. The funding is directed towards one particular type of grant: those that support “safe and healthy students.”46 These grants provide flexibility for school districts to make investments in initiatives that reflect the needs of their students, including drug and violence prevention programs, mentoring and school counseling, and positive behavioral interventions and supports.

It also appropriated $50 million to expand the “21st Century Community Learning Centers Program” (CCLC), which supports activities for school-aged children during non-school hours. The BSCA provided this funding as a supplemental 21st CCLC award to states that will remain available through September 2023. Local entities may generally use these funds for student-centered activities, such as academic enrichment learning programs, mentoring, tutoring, programs to support a healthy and active lifestyle, programs to support families actively and meaningfully engaging in their child’s education, drug and violence prevention programs, counseling programs, and programs that build career competencies and career readiness. In particular, the BSCA requires the Department of Education to increase support for evidence-based practices that increase attendance and school engagement, both of which are critical to reducing gun violence among school-aged youth given school engagement is one of the best protective factors against crime and violence involvement.47

The Uvalde Report: A Path Forward for a Community—and Nation—Struggling to Heal

Kristopher McLucas, Mike McLively, Paul Carrillo—May 23, 2023

Finally, the BSCA appropriated $1 billion over five years to expand the “School-Based Mental Health Services Grant Program” (SBMH) and the “Mental Health Service Professional Demonstration Grant Program” (MHSP), with $500 million going to each program. The SBMH program funds state education agencies to increase the number of qualified mental health service providers that provide school-based mental health services to students in local education agencies with demonstrated need. The MHSP program supports innovative partnerships to train school-based mental health service providers for employment in schools to expand the pipeline of high-quality, trained providers and address the shortages of mental health service professionals in high-need schools.

Each of these funding streams is supplemental to funding provided through regular annual appropriations bills. By supplementing the funding this way, Congress in effect recognized the inadequacy of the amounts regularly appropriated for these programs.

The BSCA also clarified that school districts are prohibited from using certain funding to purchase firearms or provide firearms training. Although ultimately proven wrong, Trump administration officials previously argued there was some ambiguity regarding the use of this type of funds for firearms or firearm training for school personnel.48

Uses of This Funding to Date

The Department of Education has taken a number of steps to ensure that this funding is used to support students and communities most in need of the additional resources. In mid-September 2022, the Department of Education issued a Dear Colleague letter regarding the available BSCA funding for the Stronger Connections grant program, which was created to disburse the new Student Support and Academic Enrichment Grants.49 The letter indicated that states should give Stronger Connections grant funding priority to school districts, and that school districts must award these funds competitively to high-need local educational agencies. The letter also provides criteria for determining whether a school district is “high-need.”

In late September 2022, the Department of Education announced nearly $1 billion available for grants to state educational agencies under the Stronger Connections grant program and soon thereafter published an FAQ document on the program, detailing how this funding may be used to support community violence intervention programs.50 The Department also hosted a four-part webinar series highlighting the program and evidence-based practices for supporting student safety and well-being.51 As of May 2023, a majority of states have started or completed grant competitions for Stronger Connections grant funding.

In October 2022, the Department of Education issued a memo for the 21st CCLC program providing guidance to states and subgrantees on the potential uses for the $50 million in additional funding provided through the BSCA.52 The memo encouraged states to prioritize subgrantees that implement evidence-based practices, including support for family engagement, trauma-informed practices, and mentoring programs built on strong relationships. In March 2023, the Department of Education hosted a webinar on the same issue.

On October 3, 2022, the Department began inviting applications for SBMH and MHSP grants.53 In February 2023, the Department announced the first of these awards, and in total, the Department has awarded $286 million in SBMH and MHSP grants across 264 grantees in 48 states and territories, with nearly half of MHSP grants going to awardees in partnership with a historically Black college or university, tribal college, or minority serving institution.54 The Department believes these investments will help to broaden access to critical mental health supports, with grantees estimating the funds will prepare more than 14,000 new mental health professionals for US schools. To support SBMH and MHSP grantees, the Department also announced a new Mental Health Personnel Technical Assistance Center. The Biden administration explained that the Departments of Education and Health and Human Services will work jointly to develop resources for states and schools on using Medicaid to fund school-based services for students dealing with physical and emotional impacts of gun violence.55

Finally, in March 2023, US Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona urged state school leaders at the Council of Chief State School Officers to use the $1 billion in funding allocated by the BSCA to support school-based mental health programs.56 He provided examples to leaders, including providing every student with a class period dedicated to mental health and well-being and increasing the number of social workers and mental health providers in schools. Secretary Cardona also suggested leaders partner with their local health departments.

Recommendations

As described above, the Department of Education has demonstrated a commitment to ensuring this BSCA funding is utilized in a manner likely to result in reductions in violence.

As the Biden administration continues to implement the BSCA, GIFFORDS recommends the Department of Education take the following actions, ensuring the BSCA funding is used for evidence-informed programming aimed to reduce gun violence among youth most at-risk of gun violence involvement:

- Update the Department’s October 2016 guidance document for the SSAE program57 to include additional allowable uses for SSAE funds and details about the Stronger Connections grant program. This document serves as the primary source of guidance on the Department’s website for the SSAE program58 and should be updated to:

- Clarify that school districts can use SSAE funding, specifically Stronger Connections grant funds, to send notices to families encouraging the safe and secure storage of firearms.

- Clarify that Stronger Connections funding can be used to help spread public awareness about the availability of extreme risk protection orders, court orders that temporarily remove firearms from people at a high risk of violence.59

- Clarify that gun violence rates in schools, and in the community surrounding a school, can be used as a factor when identifying which schools are persistently dangerous under the Elementary and Secondary Education Act and should be prioritized to receive SSAE grants, including Stronger Connections grants. Under SSAE grants, local education agencies must prioritize the distribution of funding to schools based on one or more of several factors, including public schools that are considered “persistently dangerous.”

- Include additional direction on how SSAE funds generally, and more specifically Stronger Connections grant funding, may be used to support community violence intervention strategies.

- Update the Department’s February 2003 guidance document for the 21st CCLC grant program, the Department of Education’s primary source of guidance, to:

- Incorporate the Department’s October 2021 Dear Colleague Letter on community violence intervention programs.

- Incorporate the Department’s October 2022 21st CCLC BSCA Memo.

- Issue a Dear Colleague Letter providing guidance on how SBMH grants and MHSP grants can address trauma associated with gun violence. The Dear Colleague letter should:

- Outline the significant trauma associated with gun violence exposure and its impact on student health and academic success.

- Specify that a high rate of gun violence is a sufficient basis for a school district to demonstrate a significant need under the SBMH and MHSP grant programs.

- Specify that trauma-informed counseling programs that aim to reduce the trauma associated with gun violence exposure are an allowable activity under the SBMH grant program.

The Department should also issue guidance and amend regulations clarifying for state and local education agencies that firearm purchases and training are a prohibited use of all Education Department grant funds, as was clarified by the BSCA.

AMICUS BRIEFS

Time and again, courts have ruled that the Second Amendment is fully compatible with a wide range of gun safety laws. Giffords Law Center and our partners frequently draft and submit amicus curiae—or “friend of the court”—briefs in cases challenging lifesaving gun laws.

Learn More

Gun Dealer Licensing

For decades, gun safety advocates have worked to direct attention to one particular loophole in our federal gun laws—the loophole that allows unlicensed gun sellers, including those selling firearms at gun shows, online, or anywhere else without a federal firearms license, to sell guns without background checks.

This loophole makes it far too easy for individuals prohibited from purchasing firearms to obtain guns through unregulated transactions. Because of it, people prohibited by law from possessing guns—like people with felony or domestic violence convictions—can easily buy a gun from an unlicensed seller, and can do so without any federal record of the transaction. According to a 2017 study, 22% of US gun owners acquired their most recent firearm without a background check—which translates to millions of people obtaining guns, no questions asked, each year.60

The BSCA did not close this loophole. It did, however, make a change to the language that determines which sellers of guns must obtain a federal firearms license and conduct background checks. In connection with this change, President Biden recently directed the attorney general to move the US “as close to universal background checks as possible without additional legislation.”61 The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) should begin implementing this directive immediately.

Background

Federal law imposes various duties on federally licensed firearms dealers. Firearms dealers must, among other things, perform background checks on prospective firearm purchasers and maintain records of all gun sales. However, federal law imposes none of these requirements on unlicensed sellers.

The Case for Firearm Licensing

Apr 23, 2020

The Gun Control Act of 1968 provides that persons “engaged in the business” of dealing in firearms must be licensed. Prior to the BSCA, federal law defined the term “engaged in the business,” as applied to a firearms dealer, as “a person who devotes time, attention, and labor to dealing in firearms as a regular course of trade or business with the principal objective of livelihood and profit through the repetitive purchase and resale of firearms,” (emphasis added).

Significantly, however, the term was defined to exclude a person who “makes occasional sales, exchanges, or purchases of firearms for the enhancement of a personal collection or for a hobby, or who sells all or part of his personal collection of firearms.” According to a 1999 report issued by ATF, the definition of “engaged in the business” often frustrated the prosecution of “unlicensed dealers masquerading as collectors or hobbyists but who [were] really trafficking firearms to felons or other prohibited persons.”62

People who commit crimes with firearms overwhelmingly obtain these firearms from unlicensed sources. The best evidence indicates that about 80% of all firearms acquired for criminal purposes are obtained from sellers who were not required to run a background check, and 96% of inmates who are prohibited from possessing a firearm at the time they committed their crime obtained their gun this way.63

Clarifying the Definition of a Gun Dealer under the BSCA

The BSCA makes a minor change to the language that determines which gun sellers must obtain a license and conduct background checks. Specifically, gun sellers would be considered to be “engaged in the business” if they sell firearms “to predominantly earn a profit,” whereas prior to the BSCA, a gun seller was “engaged in the business” if their principal objective for selling firearms was “livelihood and profit.”64

This change provides an opportunity for ATF to update its regulations and significantly reduce the scope of the background check loophole by requiring more gun sellers to become licensed and conduct background checks on potential purchasers. However, the loophole that allows unlicensed sellers to sell guns without conducting background checks would remain open.