The Uvalde Report

A Path Forward for a Community—and Nation—Struggling to Heal

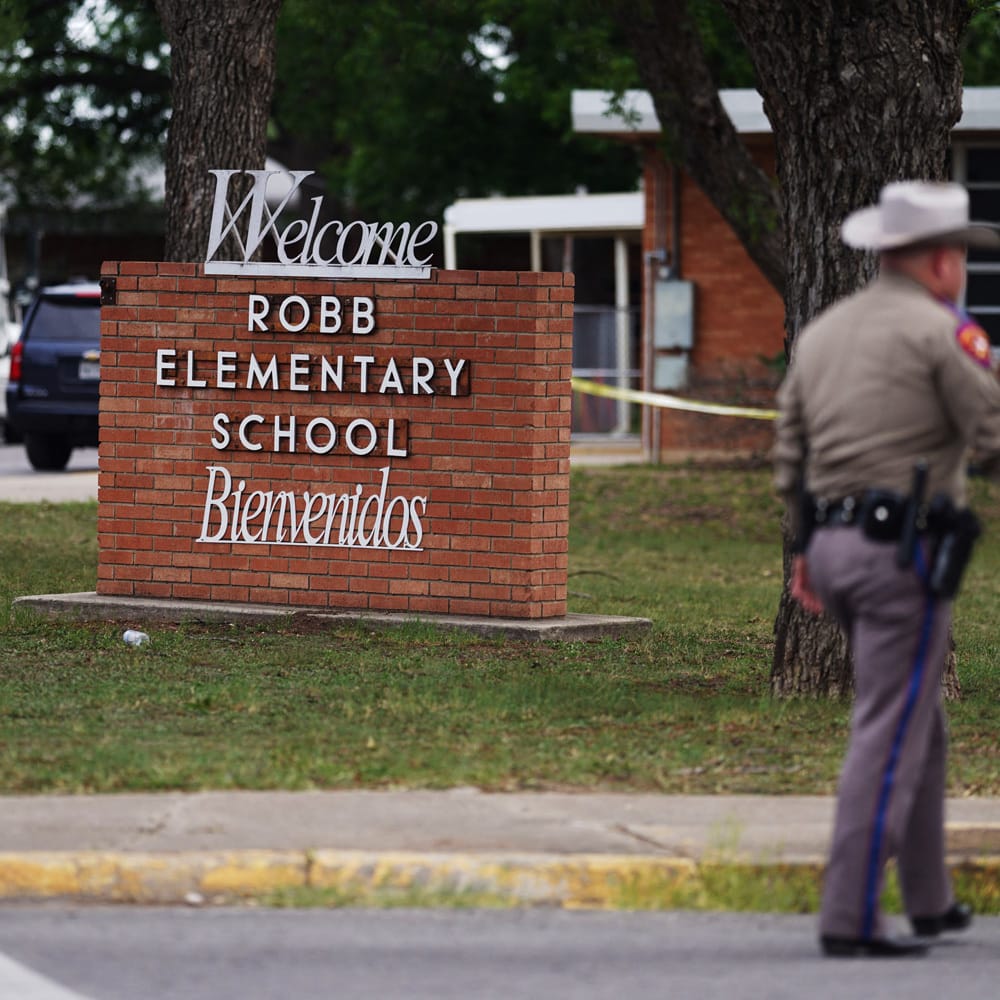

On May 24, 2022, an 18-year-old former student of Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas, shot his grandmother in the face during a dispute in her home over a cell phone bill. He then stole her Ford F-150 and drove it to the Robb Elementary campus, where he crashed into a ditch before climbing a fence and eventually making his way into a series of connected classrooms. He was armed with a single semiautomatic AR-15 rifle and seven large-capacity ammunition magazines, all of which he legally bought only days before.1

The Uvalde Report: Executive Summary

Despite recent investments in school security—made in response to another devastating mass shooting at a high school in Santa Fe, Texas2—and the presence of an armed school resource officer, the shooter was able to enter classrooms 111 and 112, where for 77 minutes, he deliberately executed 19 children and two teachers, in addition to injuring 17 others, before being shot to death by members of the United States Border Patrol Tactical Unit.

Local police who first responded to the scene initially approached the classroom, but then moved back after coming under fire from the gunman. Instead of engaging, dozens of law enforcement officers formed a perimeter and physically detained parents from making an effort to reach their children, who were heard yelling outside for help from within their classrooms. While awaiting a law enforcement intervention for more than an hour, the terrified students took extraordinary measures to survive.

It’s not within the scope of this report to recount all of the horrific details of this tragic day, which are available in many other public accounts. What matters most is that 21 precious lives were taken and countless members of the Uvalde community will be forever impacted, with physical and psychological wounds that will take years and decades to heal.

This report is not about assigning blame, although we agree with a report by the Texas House of Representatives Investigative Committee that calls out the many “systemic failures and egregious poor decision making” by many different agencies and government systems that contributed to this needless loss of life.3Instead, this report is intended to identify the ongoing needs of Uvalde residents in the wake of this unthinkable act and to offer concrete ways that different systems—but especially the local, state, and federal governments—can help to better facilitate the healing of this community and to prevent other such tragedies from happening in the future.

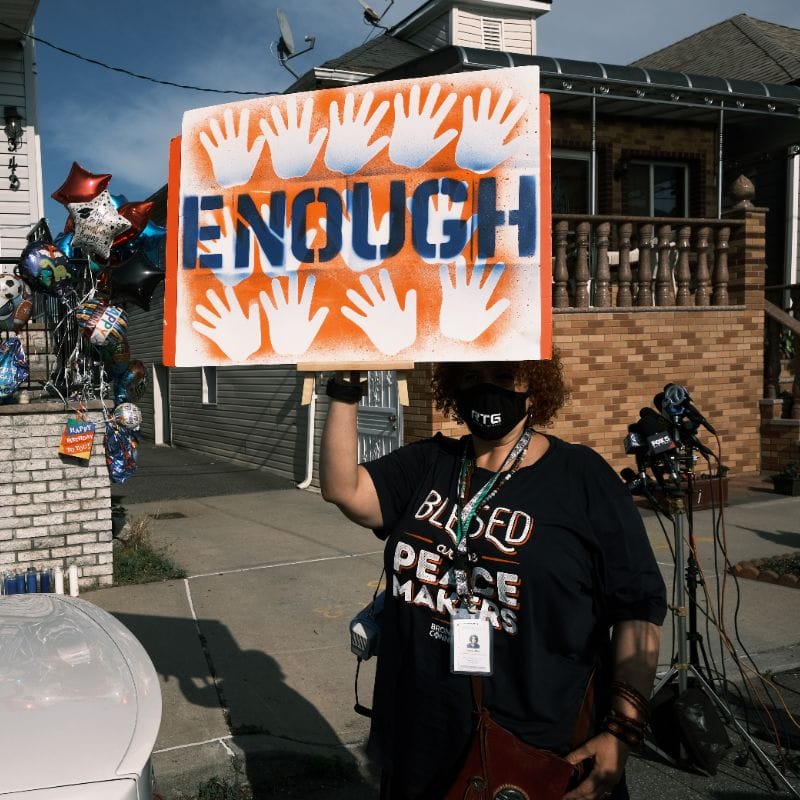

Because gun violence is such a common fixture in American life, this report is also intended to benefit communities around the country that are responding to the widespread trauma of both mass casualty shootings and the constant drumbeat of day-to-day violence on our city streets that may be of less interest to the media but is no less damaging to entire neighborhoods.

MEDIA REQUESTS

Our experts can speak to the full spectrum of gun violence prevention issues. Have a question? Email us at media@giffords.org.

Contact

Uvalde is a microcosm of the United States, and the tragedy at Robb Elementary has laid bare divisions that have existed for decades based on race, gender, and socioeconomic status. In order to heal and move on, Uvalde—much like our entire nation—requires a government response that is trauma-informed, built on accountability, and designed to unify the community around its common humanity and shared suffering.

To its credit, Congress responded to the tragedy in Uvalde with the first major legislative action on gun safety in decades by passing the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act (BSCA) in June 2022, which President Biden quickly signed into law. This lifesaving federal legislation strengthened background checks for purchasers under 21, allocated significant funding for community violence intervention programs, incentivized states to establish and implement extreme risk laws, and addressed the intimate partner loophole as well as the scourge of gun trafficking.

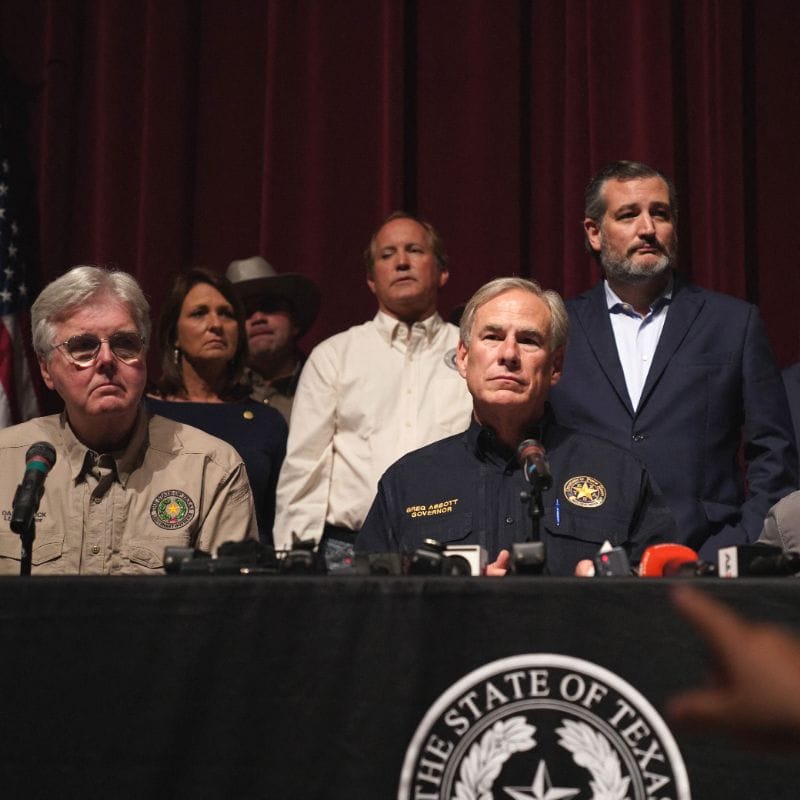

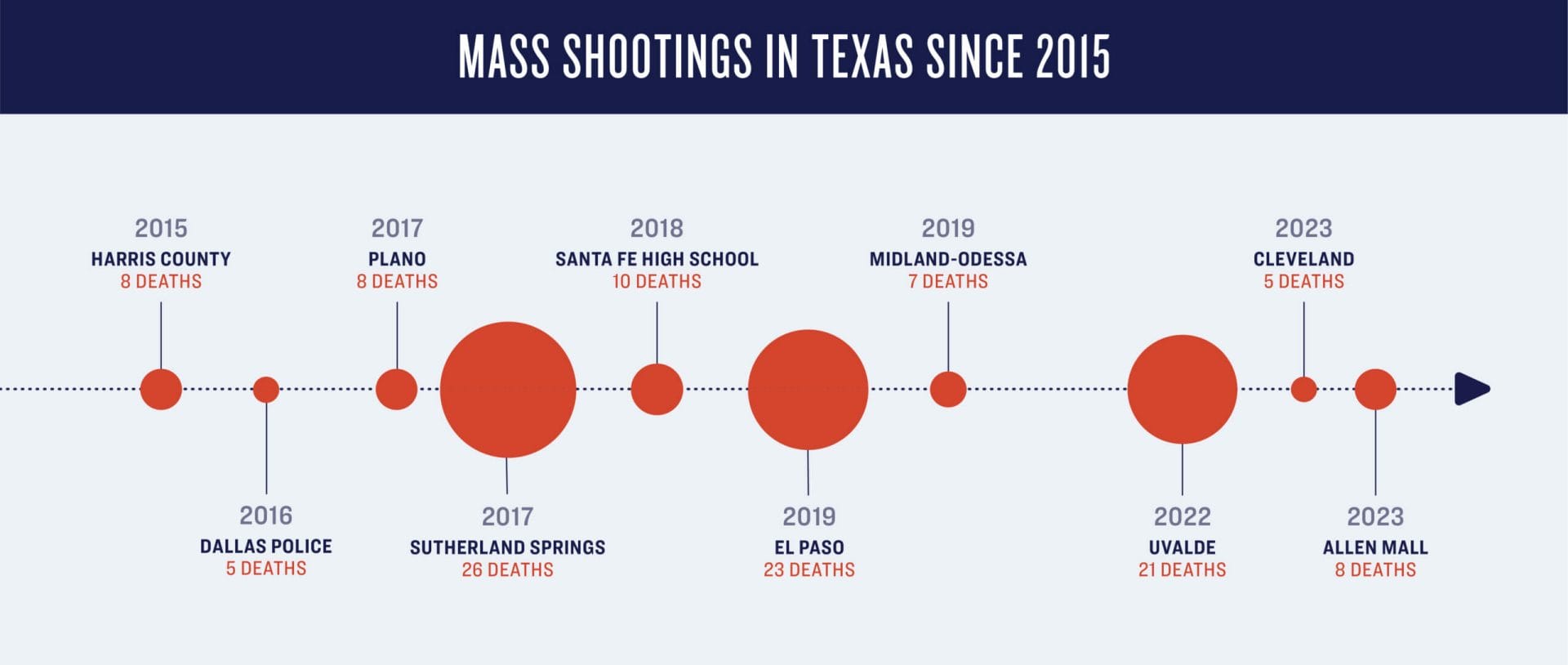

Other politically conservative states, including Florida, have come together in recent years to enact policies to address senseless gun violence—but one whole year after the tragedy at Robb Elementary School, Texas has failed to take action. Officials continue to offer thoughts and prayers following the unending cycle of gun violence–related tragedies—most recently following the shooting at an outlet mall in Allen, Texas, and in a neighborhood in Cleveland, Texas, both incidents involving AR-15 style rifles and killing young children—but no significant gun safety legislation has passed in the state. In fact, the only major movement has been in the opposite direction, with the Texas legislature passing and Governor Greg Abbott signing a law in 2021 allowing people to carry loaded and concealed handguns in public without a permit.4

GIFFORDS: Texas Republicans Betray Uvalde Families

May 10, 2023

As this report will discuss, even if Texas leaders don’t have the courage to act directly on guns, there are a number of other policy areas that require urgent attention, including reforms to the state’s victim compensation program as well as dramatically increased investments in the mental health system and community violence intervention programs, that will help save lives from gun violence and heal communities that have already been impacted.

An unwillingness to address guns directly is not a valid excuse for inaction on this issue.

One year after 21 lives were needlessly taken, many survivors, their families, and members of the community are still attempting to rebuild. But there remain numerous ways in which the needs of the Uvalde community are not being met. We hope this report will help bring those needs to the forefront of our leaders’ attention and spur more effective action to help meet them—in Uvalde and beyond.

The lives that were lost on this day can never be replaced. But we can honor them with action, by fighting for the kinds of deep, systemic changes that will bring healing, protect others, and ensure that these young lives were not lost in vain.

America will never forget them, and we dedicate this report to their memory:

Nevaeh Alyssa Bravo, 10; Jacklyn Jaylen Cazares, 9; Makenna Lee Elrod, 10; Jose Manuel Flores Jr., 10; Eliahna Amyah Garcia, 9; Uziyah Sergio Garcia, 10; Amerie Jo Garza, 10; Xavier James Lopez, 10; Jayce Carmelo Luevanos, 10; Tess Marie Mata, 10; Maranda Gail Mathis, 11; Alithia Haven Ramirez, 10; Annabell Guadalupe Rodriguez, 10; Maite Yuleana Rodriguez, 10; Alexandria Aniyah Rubio, 10; Layla Marie Salazar, 11; Jailah Nicole Silguero, 10; Eliahna Cruz Torres, 10; Rojelio Fernandez Torres, 10; Irma Linda Garcia, 48; Eva Mireles, 44.

Project Overview

Like all Americans, we were shocked and saddened by the news of the shooting in Uvalde. Within days, Paul Carrillo, vice president of the GIFFORDS Center for Violence Intervention, was on the ground in Uvalde meeting with victims, family members, and city leaders to find out what kind of support the community might need in the wake of unimaginable tragedy. In the ensuing weeks, residents expressed numerous frustrations and a desire to have their voices heard in the midst of a tumultuous process that often left them feeling overwhelmed and, at times, unheard and unseen—particularly by various government actors.

As a result of those conversations, we launched this project as part of our ongoing commitment to save lives from gun violence and provide comprehensive support to communities impacted by this uniquely American epidemic. The primary goal of this project is to understand the ongoing needs of Uvalde community members—with an emphasis on direct survivors and their families—and to identify the resources, services, and other types of support necessary to help them recover. In a nation where mass shootings are on the rise,5 this report is also meant to help inform a more effective and trauma-informed response to senseless acts of violence in other American communities.

A secondary goal of this report is to identify policy reforms that may help to both avoid future tragedies and improve services and support for victims not only of mass violence, but also the far more common instances of day-to-day community violence.

El Informe Uvalde: Resumen Ejecutivo

Our team for this project includes individuals from multiple organizations with specializations in mental health, trauma, crisis response, government policy, and social services. One of our team members is originally from Uvalde and still has many family members there.

Before visiting Uvalde for multiple on-the-ground visits, the team identified stakeholders such as family members and key community leaders who were impacted directly or indirectly by the shooting at Robb Elementary School. We developed a sampling matrix to capture diverse perspectives and a semi-structured, trauma-informed interview guide to ensure consistency in the questions asked of each individual.

Our team conducted both one-on-one and focus group–style meetings in English and Spanish at emotionally safe and confidential locations in the town. To help ensure the well-being of our team members, we contracted with a mental health professional, Dr. Tonya Wood, Ph.D.,6 to assist our team with processing and self-care practices. In total, we spoke directly with dozens of members of the Uvalde community and reviewed hundreds of documents, articles, and government reports.

While no community is a monolith, this report is designed to identify the common themes that arose across different stakeholders. Our team will continue to share the findings from this project with Uvalde residents to ensure accuracy and to center the survivors’ voices and needs.

To the residents of Uvalde, we are incredibly grateful to you for welcoming us into your community during an incredibly challenging time and for sharing your experiences and grief with our team. We grieve alongside you, and sincerely hope this report will be a useful resource to support you in your ongoing journey of healing.

The Uvalde Community

Uvalde is a rural city of approximately 15,000 residents, located in southwest Texas about 80 miles west of San Antonio. With nearly 80% of the population identifying as Latino or Hispanic, Uvalde is a proud community with a rich history, and is part of a larger region that consists of 32 counties running from Llano County to a 200-mile stretch of the Texas/Mexico border between Del Rio and Laredo. This is a region with a lower population density and a much higher rate of poverty than the statewide average, with 60% of Uvalde County’s children and youth living in poverty, compared to the statewide average of 40%.7

As a tight-knit community where everyone knows each other, Uvalde is also a community that has experienced many divisions along socioeconomic and racial lines that have persisted since the city’s founding in the 1850s. Many older residents described their struggles to gain economic opportunities—from business loans to job opportunities—in the face of blatant discrimination based on their race. This historical racism was exemplified by a student-led school walkout in 1970 in protest of rampant racism in the Uvalde educational system.8 It is a system that has long been segregated, with Hispanic students attending Robb while most white students attended Dalton Elementary School.9

The leadership of the city, which is more than 80% Latino, remains mostly white. “At the center of town on the courthouse grounds, you’ll find a monument to Jefferson Davis, the Confederate president—installed when the Ku Klux Klan dominated Uvalde politics,” wrote one former resident.10

We discuss race and racism in this report not to point fingers or cast judgment, but because grappling with these issues will be critical to the community’s ability to heal and move forward in unity from the tragic events of May 24, 2022.

It’s also important to note that Uvalde is a city with a tremendous amount of resilience and assets. In interviews, community members identified numerous strengths of Uvalde residents, including good people, strong faith, hope, and grit. “This shooting has opened our eyes,” said one resident. “There’s a tremendous opportunity for positive change if we can come together.”11

Finding ways to overcome divisions—especially those connected to race, economics, and politics12—will be key to moving forward as Uvalde marks the one-year memorial of this devastating shooting.

A Trauma-Informed Approach to Gun Violence

Trauma generally results from a distressing event that causes life-threatening physical and/or emotional harm that can impact one’s mental, physical, emotional, social, and spiritual health.13 As one mental health organization aptly summarizes, “Experiencing a traumatic event can harm a person’s sense of safety, sense of self, and ability to regulate emotions and navigate relationships. Long after the traumatic event occurs, people with trauma can often feel shame, helplessness, powerlessness, and intense fear.”14

Trauma can also be experienced at multiple levels: individually, through interpersonal relationships (e.g., adverse childhood events), and collectively (e.g., racism, discrimination). Often, collective trauma contributes to the exposure of trauma at the individual and interpersonal level.

Gun violence is an increasingly common source of trauma in the United States and one that leaves lasting effects within entire communities.15 This is why a trauma-informed approach is necessary to facilitate community healing and inform our collective response to gun violence.

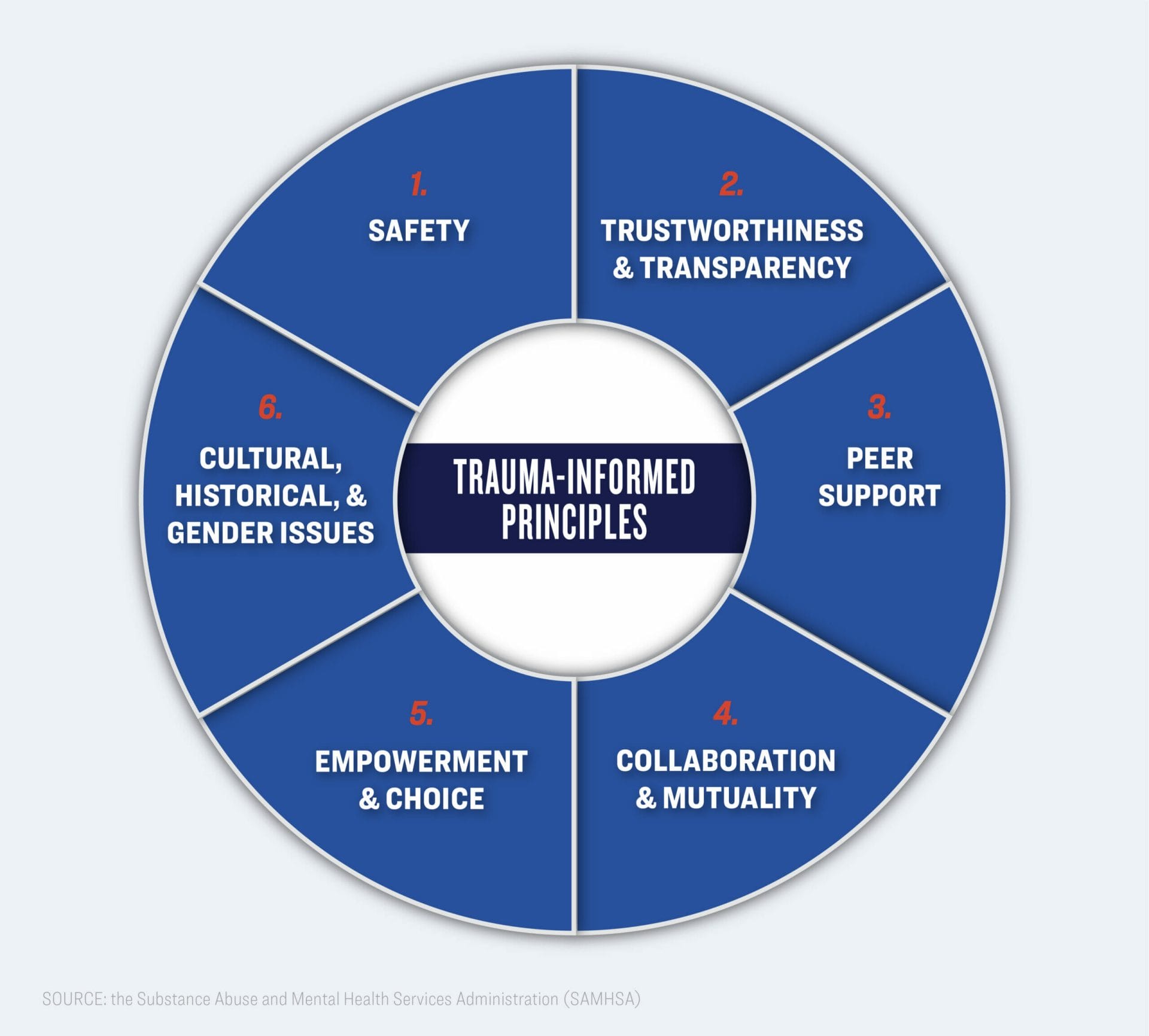

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) has identified six trauma-informed principles as a best practice framework to support survivors of trauma. These practices emphasize a trauma survivor’s healing by creating strong, stable, and supportive relationships to build resilience and reduce their mental health symptoms.16 This approach also actively seeks to prevent practices that can retraumatize the survivors. This report will incorporate this framework and identify how effectively these six trauma-informed principles have been incorporated in Uvalde:17

- Safety

- Trustworthiness and Transparency

- Peer Support

- Collaboration and Mutuality

- Empowerment and Choice

- Cultural, Historical, and Gender Issues

These principles will be referenced throughout this report to highlight the strengths and gaps in response to the Uvalde shooting.

The tragic events of May 24 will impact community members in Uvalde for many years to come. The scientific literature is clear that mass shootings increase rates of mental health issues, raise the risk of suicide—especially among youth and young adults—and reduce the overall sense of community identity, safety, and well-being.7 Mass shootings also impact community members differently based on their proximity to the shooting—for example, a survivor that was in the classroom may have a different response compared to a student that was not in the classroom but heard the gunshots. These impacts are not just experienced in the days, weeks, and months immediately following a mass casualty event, but ripple through the community for years.

Months after the shooting at Robb, interviews with Uvalde family members confirmed this. Families reported that children had high levels of anxiety and stress—difficulty sleeping at night was a commonly reported symptom—and dramatically altered behaviors. “My daughter cries every time she hears a siren now,” reported one mother. “She used to be open, but now she’s totally withdrawn and just not herself since this happened.” Another parent stated, “My child survived, but she is not the same.”11

An additional common consequence of mass shootings is that they tend to lay bare pre-existing community divisions—and Uvalde is no exception. Despite the ubiquitous signs saying “Uvalde Strong,” many residents interviewed for this report expressed concerns that the Robb tragedy had further exacerbated divisions that already existed along racial, economic, and political lines. “The pain runs deep in Uvalde,” said one resident.18 “We’re talking about decades of pain, racism, and separation—this is not just about May 24, this is a catalyst.”

A focus group of Uvalde residents identified some of the most common feelings that are continuing to arise in the community as the one-year memorial of the shooting approaches, which include anger, sadness, grief, resentment, mistrust, numbness, exhaustion, fear, and a sense of lost identity. Those directly impacted have struggled to receive consistent and quality mental health services. As a range of responses to the shooting continue to emerge from community members, it will be critically important for the people of Uvalde to have access to stable, consistent, long-term mental health services.

“We don’t just want to put a Band-Aid over it and leave,” said pediatric psychologist Jeffrey Shahidullah, Ph.D., who is an assistant professor at the University of Texas at Austin’s Dell Medical School, and who helped staff a walk-in clinic for Uvalde residents seeking on-demand mental health support in the days and weeks immediately following the shooting.19 “We need to create a trauma-informed community, because the situation doesn’t end once the traumatic event is over.”

This is backed up by studies showing that, over time, mass casualty shootings can influence the manifestation of psychological disorders such as depression, anxiety, and PTSD, as well as somatic and medical conditions.7 For example, in the first year following a disaster, PTSD prevalence ranged between 30–40% in direct victims, 10–20% in first responders, and 5–10% in community members. Additionally, mass shootings increase symptoms of PTSD, depression, and anxiety of survivors in relation to the degree of physical distance and social proximity to the shooting.20

Our inventory of the needs of the Uvalde community begins not with what’s missing, but with the assets that are already in place. Uvalde is a community that has many strengths that have reinforced its residents’ capacity for resilience. These strengths provide the foundation to improve the well-being of everyone in Uvalde, and to bring healing to those who have been impacted by this tragedy.

Many survivors and their families referenced the strong social connections throughout the community as important for their healing journeys. Social connection refers to how community members relate with each other, and it is associated with increased health-related protective factors.21 Social connections are common in rural communities and are often formed through close family ties, long connections to the community, and similar faith-based communities.22

In Uvalde, a few people we spoke with mentioned how, despite fractures in the community that occurred post-shooting, community members have found ways to lean on each other for support. One interviewee mentioned that “Uvalde has the ability to come together when needed the most, despite our pain and differences.”23

Several of the surviving students’ parents mentioned how they have formed a community of support by sharing information and providing emotional support to each other. They spoke about how many of them are in the same text group, and when one person receives information they make sure to share this information with the other parents. They also discussed how their children will often spend time together and “when [the parents] are alone they will talk about [the shooting] with each other.”24

Additionally, a local mental health provider indicated that he is offering a grief support group to community members as an opportunity for survivors to connect. He mentioned that this group does not require participants to complete any documentation or even provide identifying information to minimize barriers to accessing support. This type of peer support is a necessary part of recovery after experiencing a traumatic event25—when survivors have access to peer support, it not only facilitates their sense of safety but also their sense of empowerment. All three of these principles are included within the trauma-informed framework discussed above, and when trauma survivors have access to these resources they experience safe and supportive environments to facilitate their healing. Therefore, these relationships are essential in facilitating healing for the families in Uvalde.

Community members in Uvalde are also connected to social support through formal institutions, such as their churches, to enhance their resilience. In Uvalde, many supportive resources have been facilitated through faith-based institutions, and several people interviewed indicated that faith and prayer have been helpful in their recovery. Connection to spirituality is associated with a decrease in trauma-related symptoms and overall psychological well-being,26 and soon after the shooting, many faith-based communities showed up in Uvalde and offered prayer and other forms of tangible support (e.g., resources, activities, etc.) for residents.27

When parents that have lost a child experience family and community support, they have increased rates of resilience post-trauma28 and a reduction in trauma-related symptoms.29 Local informal support systems also provide a significant bridge of resources for families impacted by the shooting. Reverend Mike Marsh from St Philip’s Episcopal Church noted that the church received packages “every day” with donations for the families affected by the shooting.30 Others we spoke with reported how their faith community has been essential in providing spiritual and financial support to assist with burial costs.31

Faith-based institutions are trusted in Uvalde, and they have been important locations to integrate other supportive services. One person we spoke with mentioned that the Bereavement Center in Uvalde has made a 10-year commitment to provide mental health services in the community. Reverend Marsh mentioned that his church has an ongoing collaboration with the Bereavement Center, including a dedicated “therapy space” for a therapist to meet with children at the church’s school.

Within a trauma-informed framework, faith-based institutions also provide a sense of safety, peer support, and cultural congruence that facilitate healing. Therefore, the collaboration between the faith-based community can reduce stigma and provide an opportunity to introduce mental health services and increase accessibility to these services.32 This type of long-term commitment can facilitate trust between the community and community providers and is also consistent with the trauma-informed principles of safety, trustworthiness, and transparency.

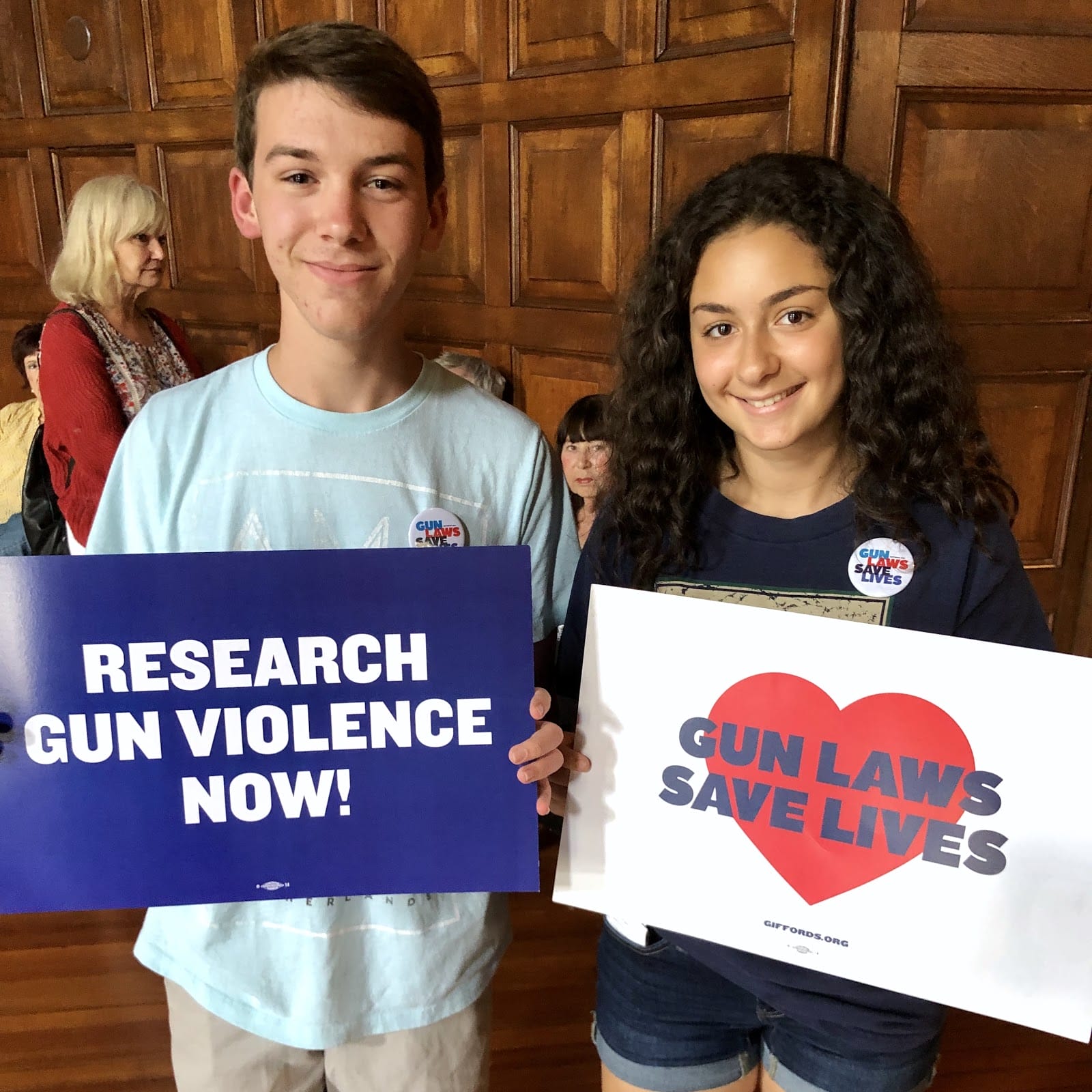

Advocacy Efforts

Immediately after the shooting, families engaged in activism to change the conditions in Uvalde and hold institutions accountable. One parent without any prior political aspirations ran for county commissioner to promote change within Uvalde.33 For some trauma survivors, engaging in advocacy is directly connected to healing from their trauma and creating change that makes meaning out of their loss.34 One parent mentioned how engaging in advocacy gave them a space to channel their grief and connect with others directly impacted by the shooting. “I stay angry… I go every week to meet with lawmakers… I don’t care if they are with me or against me—our kids deserve better.”35

Empowerment for trauma survivors is consistent with trauma-informed principles for healing because it gives survivors an opportunity to bring awareness to and change the conditions that contributed to their initial exposure to the trauma.36 Currently, many of the surviving parents and youth from Uvalde are advocating at a federal, state, and local level to prevent future incidents of gun violence and hold those in power accountable.37 Advocacy efforts have been connected to recovery for other survivors of gun violence and have contributed to meaningful social change through education and mass mobilization.38

Survivors in Uvalde should know that many resources exist to help channel grief into positive actions for change, including Survivors Empowered, an organization created by Sandy and Lonnie Phillips after they lost their daughter, Jessi Ghawi Redfield, on July 20, 2012, in the Aurora, Colorado, massacre. Survivors Empowered was designed to help provide support to people affected by gun violence, both in its immediate aftermath and long-term.

In 2022, GIFFORDS partnered with Sandy and Lonnie to create From Healing to Action: A Toolkit for Gun Violence Survivors and Allies, a resource we hope will be useful to those in Uvalde who have been impacted by the shooting at Robb. One crucial takeaway from the report is that no survivor is alone.“We have traveled this road with many friends and allies, and we are proud to call Gabby Giffords, and her organization, GIFFORDS, treasured allies and resources,” wrote Sandy and Lonnie.

The shooting at Robb Elementary is just the latest example that brings to light the history of community racial and socioeconomic divisions that can hinder long-term healing in a community. Trauma-informed principles highlight the importance of addressing how history and discrimination play into the impact of their current trauma. Additionally, this creates an opportunity for the community to acknowledge its strengths while also addressing the underlying conditions that have contributed to community harm.39 This form of community healing also includes tangible opportunities for community members, specifically youth, to advocate for and gain the influence to implement the changes needed within their community.40

In Uvalde, youth-led advocacy movements have a history of initiating change in the community.9 Similarly, gun violence prevention movements led by young people, such as March for Our Lives and Students Demand Action, have allowed different communities to add their voice to the fight against gun violence and advocate for change at the state and federal levels. These approaches empower youth as agents of change and acknowledge both the impact of the trauma and the opportunity to envision and impact their futures.41

Nontraditional Healing Approaches

Using nontraditional healing modalities, such as art and animal-assisted therapies, can be an effective way to treat trauma-related symptoms—and the Uvalde community has prioritized this following the Robb Elementary shooting. One interviewee indicated that they believed having access to nontraditional mental health approaches was helpful for her child. She mentioned that her daughter had access to “therapy dogs” soon after the shooting and noted that she believed it was helpful; however, her daughter did not have access to this resource long-term.

This type of emotional support can be effective for trauma survivors,42 but if it is not consistent it can be disruptive.36 Another person we spoke with indicated that she believed that her daughter would benefit from art-based therapies to process her trauma in addition to traditional talk therapy, but she did not know how to connect her daughter to this resource. This form of therapy can be an effective approach in treating child survivors of trauma and even reduce the stigma associated with receiving mental health care.43

In Uvalde, there are also community members seeking healing and community connection through nontraditional therapies.44 These formal and informal communities of healing can provide trauma survivors an opportunity to seek healing in a non-stigmatized way. For example, the Virginia-based HEB Foundation hosted a camp free of charge for survivors from Uvalde.45 Utilizing trained counselors, Camp Healing Day Camp not only provided a safe space for the children but educated parents on common trauma responses, while also integrating art as a way to facilitate healing for young survivors. Additionally, these trauma-informed strategies provide safety and opportunities for peer support for the survivors and their families.

While Uvalde continues to exhibit many strengths in the wake of the tragedy at Robb Elementary School, there are still significant challenges and gaps it faces when it comes to meeting the ongoing needs of the community. This section will highlight the major gaps community members identified that have impacted their ability to heal since the shooting on May 24, 2022.

History of Racism and Socioeconomic Division

Uvalde’s history of racism and socioeconomic divisions has impacted the community and hindered its recovery. Several interviewees directly and indirectly referenced the history of racism and discrimination that has existed in the community, specifically along racial and socioeconomic lines.46 They often noted two specific examples of how racism and discrimination have occurred within Uvalde: 1) A historic (and currently informal) designation of a “white people park” and a “Mexican park”; and 2) The firing of a well-respected Mexican teacher and the subsequent backlash from the community a few decades ago.

In 1970, when the mostly white school board decided not to renew the contract of popular fifth grade teacher Josué “George” Garza at Robb Elementary School, students and parents across the district organized a mass protest, with more than 600 students refusing to attend classes.47 “That was like a climax to a chain of injustices that had been occurring,” Garza said in a 2016 interview.48

The students’ list of demands included hiring more Latino teachers and requiring teachers to be able to correctly pronounce the name of Hispanic students. The walkout, which became one of the longest boycotts of its kind during this period of Chicano activism in America,49 “sparked a class-action discrimination lawsuit against the school district that led to a desegregation order and decades of court-ordered monitoring of the district.”9

Many residents interviewed for this report felt that while conditions have improved since the time of the walkout at Robb Elementary, racism remains a part of their daily lives. “Racism is alive and well here in Uvalde,” said one local faith leader.50 Referencing the example noted above of racial discrimination in Uvalde, he added, “For instance, we still have two parks that are informally separated for use by white families and Hispanic families.”

The history of the struggle for racial justice in Uvalde is not sufficiently taught in the area’s schools. “I grew up not that far from Uvalde,” said Brett Cross, who lost his 10-year-old nephew and adopted son, Uziyah Sergio Garcia, on May 24, “and I had never heard about the walkout in school. There’s no acknowledgment of the systemic racism that’s still here.”35 And despite decades of court monitoring of the education system, “the Uvalde public schools today continue to reflect the vestiges of historical discrimination against children of Mexican descent and origin, who constitute about 90 percent of the students at Robb Elementary.”51

However, remnants of this history are very much present within the community—for example, the resulting federal school desegregation order first entered in the 1970s was only lifted a few years ago.9 Many people we spoke with reported their belief that the city has not adequately addressed its history of racism and discrimination and that ongoing discrimination is also seen in the lack of resources to address substance misuse, homelessness, and the absence of low-cost youth activities in Uvalde.

Within a trauma-informed framework, one also has to consider the historical, cultural, and community context in which the trauma occurred in order to facilitate healing and resilience. The lack of perceived social support (i.e., a history of racism and discrimination) from other community members is associated with negative mental health functioning for survivors of trauma.52 This has resulted in poor access to resources, which in turn increases the survivors’ vulnerability to experience trauma-related responses while simultaneously decreasing their resiliency factors that can promote healing. It’s in the interest of everyone in Uvalde to find ways to reconcile the divisions that are holding back the healing process.

Insufficient Trust and Transparency in Government Systems

Mistrust of institutions has surfaced as a theme with those we interviewed, especially the institutions that have a history of perpetuating racism—such as the school system and government. Interviewees referenced the history of racial segregation, income segregation, and the lack of faith in government leaders as factors that contribute to their low levels of trust. Several interviewees referred to the previously mentioned community uprising after a Mexican American teacher was fired and the lack of representation of Hispanics within leadership.

Social mobility and the perception that government actors will generally “do the right thing” are both associated with lower rates of firearm violence.53 The history of racial dynamics influenced how Uvalde residents perceived the response from government leaders to the shooting—especially the law enforcement response. Several interviewees mentioned that “the response would have been very different if all white kids were killed.”

When working with trauma survivors using a trauma-informed approach, systems and services providers must consider the historical context of the community and how this could contribute to their low levels of trust.36 By understanding the historical context of the trauma through a trauma-informed lens, service providers can not only build trust with the survivors but also understand why they might be hesitant to engage in services.54

When discussing the lack of trust and transparency, several people we interviewed referenced their limited access to information from the school district, local leaders, and state government on how decisions were made during and after the school shooting. Several parents advocated during school board meetings for greater accountability from local leaders, and we were told that there is currently a lawsuit against the Uvalde District Attorney for information on the outcome of the internal affairs investigation.

Many interviewees mentioned that they expected changes after the shooting, such as building a fence around the school and installing more security cameras, but that this has not yet happened or was not consistent across all of the schools. Additionally, those we interviewed reported that no one from the school district ever talked to the victims’ families. Several parents noted that they have not received an apology from any local or state leaders, and one parent said, “The closest thing we got [to an apology] was a backhanded apology, and [they] said other people failed as well.”35 A lack of trust and transparency from critical institutions can hinder the community’s long-term recovery, and this is evident in Uvalde.

The interviewees expressed a similar sentiment about law enforcement. Community members reported that they do not feel that the police have been transparent in their processes regarding the shooting. One person noted, “There is mistrust, and people are wondering if law enforcement did enough… Some want all school and city police removed.”23 Several people we interviewed indicated that there has been a history of distrust with law enforcement in the community, and that this distrust has grown since the subsequent reports of how law enforcement responded to the incident. “The police system in Uvalde is bad… Not good, not trustworthy.”35

The perceived lack of transparency from the local educational system, law enforcement, and government contributed to this distrust. Many community members expressed their frustration with the government’s response to providing mental health services and indicated that the services did not adequately meet the community’s needs.55 Several interviewees mentioned that social service providers have not been clear on the process and time for receiving support and noted that the process to obtain financial support is complicated.

From a trauma-informed perspective, the lack of trust and transparency can negatively contribute to trauma symptoms. This is why transparency is one of the key principles of a trauma-informed response, and why it’s necessary to facilitate healing and promote safety for trauma survivors.56 A perceived lack of transparency, coupled with the history of racial dynamics in Uvalde, will negatively impact the survivors’—and the entire community’s—process of healing, and it must be addressed more directly going forward.

Lack of Access to Mental Health Services

Long-term mental health services are desperately needed to address the impact of this tragedy on the Uvalde community. Survivors of gun violence have an elevated risk of experiencing poor mental health outcomes such as post traumatic stress disorder, major depressive disorder, and substance misuse.57 The symptoms can manifest in the months and years following the initial traumatic experience, and are often associated with poor functioning in school, increased behavioral symptoms, and decreased social functioning.58

Survivors of the mass shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary in Newtown, Connecticut, for example, have recommended that the Uvalde community plan for long-term impacts. As Stephanie Cinque, founder of the Resiliency Center of Newtown, described, “Five years was just touching the ‘tip of the iceberg’ in Newtown as many kids who were in elementary school during the mass shooting did not process their trauma until their teenage years.”59

Therefore, while many services were provided to the Uvalde community immediately following the incident, it’s likely that they may not be adequate to address the long-term consequences of the shooting. The systems of care need to develop strategies to identify high-risk youth at various time frames to ensure they receive appropriate mental health services.

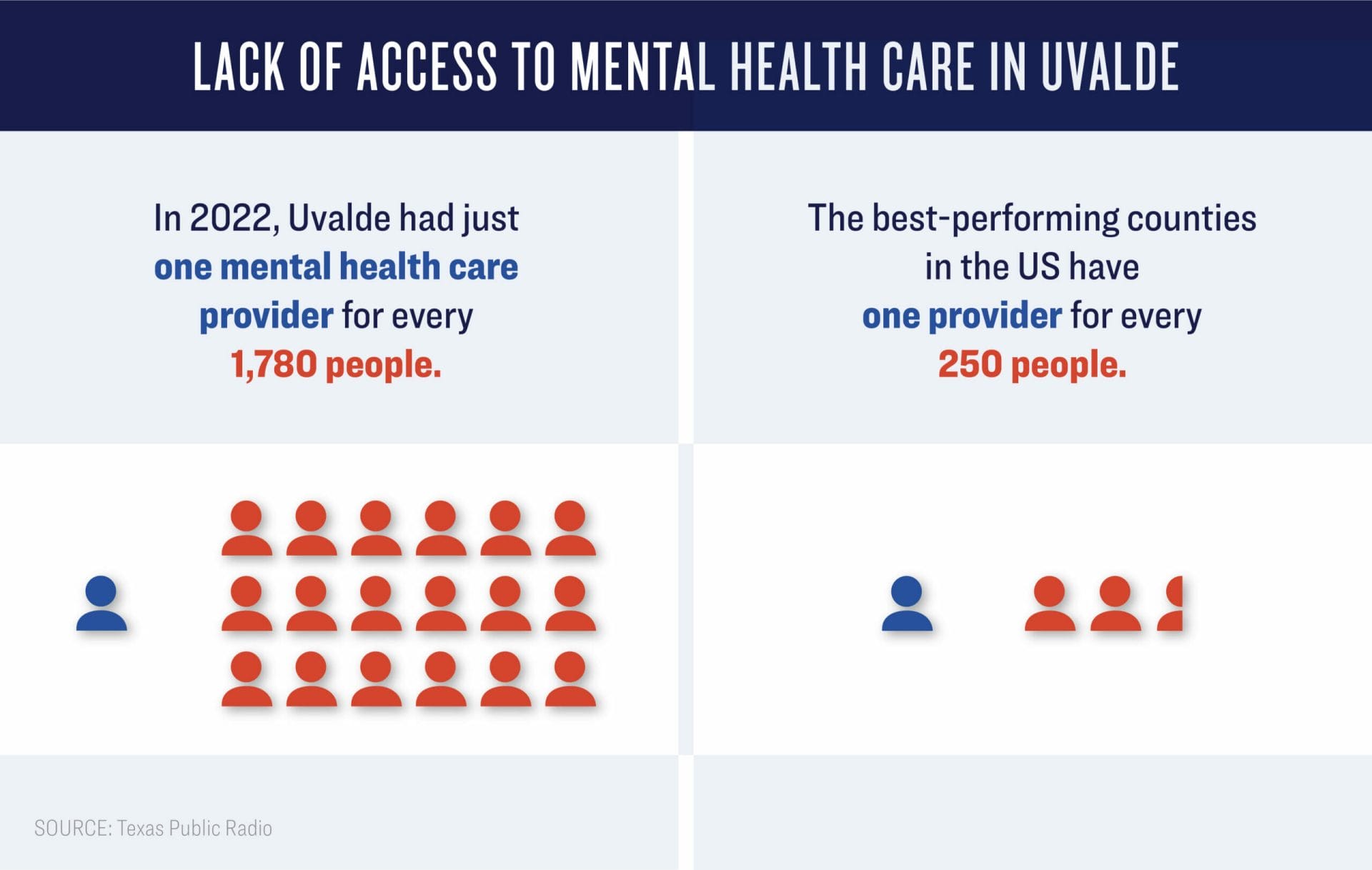

Within Uvalde, many people we spoke with discussed the impact of the lack of access to mental health services within their community. According to the Texas Department of Health and Human Services rankings for 2022, Uvalde had just one mental health care provider for every 1,780 people.60 For context, the best-performing counties in the United States have one provider for every 250 people.

Access to mental health services in rural communities is generally limited, despite the significant need for resources,61 so in many ways Uvalde’s lack of access to mental health services is not unique.60 A parent of one of the survivors indicated that they initially needed to travel to San Antonio for mental health services before getting connected to local providers. The disparity in access to care is more profound for intensive mental health treatment such as psychiatry and specialty care.62

The Southwest region of the United States, including Texas, has some of the nation’s lowest rates of mental health providers, especially within rural communities.63 Texas is also ranked second to last nationally on mental health workforce availability64 and was rated as having the least access to mental health services in the United States, especially for youth.20 It’s estimated that approximately 75% of youth with major depressive disorder do not receive mental health treatment.65 This was a critical gap before the shooting at Robb Elementary, and it will only become more pressing in the months and years to come, as communities routinely experience dramatic increases in demand for mental health services in the wake of mass casualty shootings.

In an attempt to address the mental health needs of the community, Texas Governor Greg Abbott allocated funds to create a Uvalde Together Resiliency Center, a collaborative effort to provide mental health support resources and financial counseling to those impacted by the tragedy at Robb Elementary.66

Some community members, however, indicated that this center did not appropriately address their needs, further highlighting the urgency for the state to invest much more in other forms of mental health support for the Uvalde community.55 Survivors of trauma experience multiple barriers to accessing services, and state policy must encourage access to as many forms of mental health services and supports as possible.67

According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s (SAMHSA) trauma-informed framework, trustworthy services are essential to promote healing and resiliency.36 Yet several factors have undermined trust in this resource. For one, the Uvalde Resiliency Center is located outside of town in an area that is underserved by public transportation and is not convenient to reach. It also proved to be triggering for survivors and family members of victims because of its association with the shooting. One interviewee mentioned that the Resiliency Center is located at the same location where parents of victims were taken multiple times after the shooting, as an area they had to go to and meet officials who were identifying families.

Service providers should ensure that the physical space “promotes a sense of safety and collaboration” and minimize potential barriers to services—in this case, this location did not provide a safe and supportive environment for community members.20

In addition, the entrance to the Resiliency Center was patrolled by local law enforcement, which can generate negative responses from families that have recently experienced a traumatic gun violence incident—especially when the pervasive sentiment is that law enforcement generally failed to keep the children of the town safe. When our team went to the physical grounds of the Resiliency Center, no staff or residents were visible, and officers guarding the tent informed us that we were the first people to come stop by that day. These issues help explain the mixed perceptions regarding the adequacy of the state’s response to the mental health needs of the Uvalde community.55

Inconsistent Services

Several people we interviewed also mentioned that they have continued to experience inconsistent access to local mental health services. Following the shooting, many mental health providers came to Uvalde from San Antonio, and interviewees were uncertain how long these services would remain in Uvalde. One father of a Robb Elementary victim, for example, opened up to a therapist despite his initial misgivings about therapy. When the therapist was reassigned, however, the father was left devastated and completely shut down, understandably unwilling to begin the process all over again.

The residents repeated this theme in several interviews. One person stated that “The Resiliency Center has a high turnover of counselors. They change all the time… People don’t want to go anymore.”11 Another parent reported that “the Resiliency Center did not work because they kept canceling on us and my daughter was denied teletherapy… they did not explain as to why.”20 This lack of consistency can create unpredictability and hinder healing. Moreover, an additional benefit of having mental health providers that are familiar with and can connect survivors to supportive local resources is that this can facilitate their stabilization after exposure to mass violence.68

It should be noted that some people mentioned they actually preferred to work with mental health professionals that were not previously connected to Uvalde. According to one interviewee, “People in Uvalde don’t want local counselors… it is a small town… everybody talks.” This highlights the importance of providing options for accessing mental health services and empowering survivors and their families with choices. According to SAMHSA’s principles of trauma-informed care, providing opportunities for choice and empowerment are essential components in working with survivors of trauma.

High Costs and Lack of Insurance

The cost of mental health care, as well as income and lack of access to insurance, are other barriers that have hindered Uvalde survivors’ equitable access to care.69 One person we spoke with mentioned that in addition to having limited access to local mental health services, they paid approximately $50 per session. Considering the cost of care also includes taking time off work and transportation cost, there are many additional barriers to care.70

This is particularly relevant in the context of Texas, which has the highest number and highest percentage of uninsured residents per capita in the nation71—and a large percentage of those with insurance in the state do not have coverage for mental health services.72 About one in five residents is uninsured in Uvalde, so this is an issue that disproportionately impacts Latino residents.73

Among Latinos with the highest need for mental health care, cost, and availability create significant barriers to access and utilization.74 Even more so, this is a group with an elevated risk of experiencing gun violence and subsequent PTSD symptoms.75 In Uvalde, a significant percentage of the survivors impacted by the shooting—directly and indirectly—are Latino. If the cost and availability of mental health care is not addressed, many survivors will simply go without access to care. Numerous community members we spoke with indicated that this was the case for them.

Stigma around Mental Health

Despite the overwhelming need for mental health services, both before and after the shooting at Robb Elementary, stigma is another significant barrier to accessing such services for survivors in Uvalde. Approximately 73% of the residents in Uvalde identify as Latino, and stigma is often cited as one of the barriers to receiving mental health services for this group, especially within rural communities.76 Latinos in the United States and Texas are disproportionately impacted by gun violence, and this barrier hinders them from accessing mental health care and contributes to their continued health disparities.77 Therefore, as one attempts to access mental health services, service providers must develop strategies to reduce the stigma in doing so.

The stigma associated with receiving mental health services is likely contributing to Uvalde survivors’ limited utilization of these services. In rural, tight-knit communities, there can be a stigma to receiving mental health services that can create a significant barrier for survivors of trauma.78 One parent we spoke with mentioned that during a fire drill, their child was triggered by the alarm and was mocked by peers because of their response. Another person mentioned how their children felt like they had a “target on them” because the therapists pulled them out of class and they felt “embarrassed.”

Culturally and linguistically appropriate care can minimize the stigma surrounding and avoidance of seeking mental health services. Therefore, one strategy to reduce stigma and improve treatment outcomes is to integrate culturally congruent interventions.79 Examples of culturally congruent interventions to overcome stigma in the Latino community include providing education on mental health in non-pathologizing ways that are not only linguistically appropriate but also incorporate other cultural elements and are disseminated in safe and trusted community locations. Uvalde service providers have acknowledged this gap and mentioned how they have intentionally recruited Spanish-speaking therapists on their teams.

Obstacles to Financial Assistance for Families

In the aftermath of the shooting, financial assistance programs offered support to the families, but the process of obtaining this support has been difficult. Several interviewees mentioned that they have taken time off of work due to their children’s increased mental health needs, but not all of them have jobs that provide benefits—meaning they face greater financial consequences for taking time off. Workers that are the most vulnerable in the labor market and do not have benefits like paid time off are at an increased likelihood of not receiving adequate care. At the same time, they are also the groups that are most vulnerable to experiencing poor mental health following a trauma.

Several families discussed the process of taking time off of work to care for their children that experienced significant trauma-related symptoms, comparing the ease or lack thereof to taking time off. One person mentioned that she could easily take time off from her job at the bank, while another mentioned that she needed to take time off from her caregiving job to care for her daughter but feared the potential risk of losing her employment and not being able to pay her bills. Families, especially those most vulnerable to experiencing negative mental health symptoms post-shooting, were stuck trying to balance caring for their children’s mental health and paying their bills.

Reverend Marsh noted that there have been several funds set up for the families directly impacted by the school shooting, such as the Texas Bridge Fund. However, many family members indicated that the process to obtain financial assistance was difficult—it required a significant amount of documentation, and it was often unclear when they would receive financial assistance. One person noted that she was concerned about paying her bills and indicated that she did not know the timeframe for when she would receive financial assistance, even after waiting weeks for a response.31

When working with trauma survivors, having clear and transparent processes to receive services is important to facilitate their recovery and promote healing.

Lack of Youth-Specific Programming and Facilities

A recurring theme for those we spoke with was a lack of youth programming in Uvalde. Access to low-cost youth programming that addresses multiple life domains (e.g., individual coping skills, family, connection to school and community) is associated with a reduction in youth violence and increased youth resilience.80 Several people mentioned the need for a sports complex, recreation center, and/or community resource center for young people, and another emphasized the importance of not only having access to youth programming but also ensuring the programming is affordable to residents.

One example of a successful youth program in Uvalde is the Road Rangers, offered through a local church. These types of programs offer youth exposure to protective factors like strategies to promote self-regulation, family support, school support, and peer support that can enhance their resilience and reduce the consequences of trauma exposure.81 One person mentioned there are several initiatives, such as the Community Health Development, Inc. to bring youth services into Uvalde through its planned community center project, but that these services will not be complete until 2024.82

Gun Violence in Hispanic & Latino Communities

—Mar 05, 2025

In addition to activities, access to green space is essential for youth development and is associated with increased community protective factors. Historically in Uvalde, schools have been places where youth can interact with each other and play. Today, unfortunately, young people in Uvalde do not have the same access. One interviewee noted that schools have started to put up large fences to prevent people from using the fields and that “this was not how it was in the past.”31

Accessing positive role models and engaging in physical activity is associated with improved resilience in trauma survivors.83 With the lack of access to formal youth activities and limited access to green space, many youth in Uvalde—especially high-risk youth—have limited opportunities to engage in prosocial activities and develop positive relationships with supportive adults. But the area has a great opportunity to change this, as there are several vacant spaces that could be converted into recreational spaces for the community. Government investment in creating more green spaces and reducing vacant land is associated with a significant reduction in crime, specifically gun-related violence,84 and it can be a cost-effective way to empower and engage community members in violence prevention efforts.85 Such empowerment is one of the key principles of a trauma-informed response to mass violence, and the local government should take advantage of the green spaces available.

It’s clear that Uvalde still has many significant and unmet needs as it approaches the one-year mark following the tragedy at Robb Elementary. The people of Uvalde are resilient and their connections run deep, but they face significant challenges—including a lack of mental health services, historical and persistent divisions based on race and socioeconomic status, barriers to accessing support and services for victims, and a lack of safe and healthy opportunities for young people. The second half of this report lays out concrete recommendations for policy changes and other actions that should be taken to help address these unmet needs.

The tragedy at Robb Elementary underscores the dire need for reforms at the local, state, and national levels. The following section explores the major themes that emerged from our conversations with Uvalde residents as well as national experts. We aim to address what’s needed in Uvalde, statewide in Texas, and across the nation in order to bring healing and safety to all communities.

These themes also provide a framework to incorporate the “Four Rs” of a trauma-informed approach: realizing the impact of trauma; recognizing how trauma exposure manifests in individuals, communities, and service providers; responding by integrating trauma-informed practices; and avoiding policies and practices that can retraumatize survivors.

Pass, Implement, and Improve Gun Safety Laws

One of the direct causes of the tragedy at Robb Elementary was the ease with which the 18-year-old shooter legally obtained an AR-15 assault rifle and numerous large-capacity ammunition magazines.

Texas has seen the second-highest number of school shootings since 2012 of any state in the nation.86 While this fact alone should catalyze a long and hard look at Texas’s weak gun laws, the sad truth of the matter is that mass shootings are just the tip of the iceberg of the gun violence epidemic. Texas—a state with a higher than average rate of gun ownership as well as some of the nation’s weakest gun laws—had more than 4,600 gun-related deaths in 2021,87 and tens of thousands more injuries. In terms of lives lost, that’s the equivalent of another 220 tragedies like the one at Robb Elementary in a single year.

Guns are involved in more than 59% of the state’s total suicides and more than 78% of the state’s total homicides, annually. In the past six decades, the state has experienced at least 19 high-fatality mass shootings that have killed a total of nearly 200 people and wounded more than 230 others. This gun violence takes an enormous toll on Texas residents in terms of pain, suffering, and loss. It also costs Texas $51.3 billion each year—$1.1 billion of which is paid directly by Texas taxpayers.88

While the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act strengthened federal laws and provided significant funding for a variety of measures, including community violence intervention programs, Texas leaders have not followed suit. Instead, in a state where gun violence is unrelenting, the legislature and Governor Abbott refuse to take meaningful action—and have instead focused on weakening existing gun safety laws.

Many survivors and family members of victims we spoke with expressed strong support for commonsense measures to regulate guns to avoid another similar tragedy. This is a divisive topic in Uvalde, as it is in the rest of the country, but support for at least some modest restrictions was expressed in most of the interviews conducted for this report—especially when it came to restricting the minimum age for firearm purchases. This section will explore this and a number of other key policies that would help to prevent the next mass shooting by keeping guns out of the hands of those who would use them to do harm.

Texas leaders must find the courage to act to save lives.

What Texas Does Well

- Mental health record reporting

- Child access prevention laws

What Texas Is Missing

- Universal background checks

- Gun owner licensing

- Extreme risk protection orders

- Most domestic violence gun laws

- Assault weapon restrictions

- Large-capacity magazine ban

- Waiting periods

- Strong concealed carry law

- Open carry regulations

- Community violence intervention funding

Raising the Minimum Age to Purchase a Firearm

The Uvalde shooter was just 18 years old when he legally purchased thousands of dollars worth of firearms and ammunition to carry out his attack. “If that law had been 21, I guarantee you he would have continued to be frustrated and not be able to obtain that weapon,” said State Representative Joe Moody, a Democrat from El Paso.89

Many in the Uvalde community interviewed for this report expressed support for gun rights, but also strongly supported the idea of raising the minimum age for purchasing firearms as a commonsense response to this and other tragedies happening around the country.90 This was a view expressed by victims and residents alike, many of whom attended a rally at the Texas Capitol in August of last year to call for raising the minimum age for purchasing semiautomatic rifles.91

It’s critical to consider that raising the age for purchasing firearms to 21 would address a host of issues beyond school shootings, including suicide and acts of community violence. Studies establish that brain development is not complete until at least age 25, particularly the part of the brain that regulates impulse control and decision-making.92 As a result, suicide attempts are at their highest rates from ages 14 to 21,93 and young people also disproportionately commit gun homicides: people aged 18 to 20 comprise just four percent of the US population but account for 17% of known homicide offenders.94 For all of these reasons, limiting easy access to firearms for people under the age of 21 is sound public policy and could have prevented the Robb Elementary School shooting.

Making changes to gun laws has never been easy in Texas,89 and raising the age limit for firearm purchases is no exception.95 However, Florida’s response to the Parkland massacre in 2018 provides a clear roadmap for Texas legislators. In Florida, a state known for being extremely friendly to gun rights, legislators passed and then-Governor Rick Scott signed legislation raising the legal age to purchase firearms from 18 to 21 and extending the mandatory waiting period for gun purchases to three days.

These provisions were passed into law with bipartisan support and signed by a Republican governor with an A+ rating from the NRA just three weeks after the tragedy in Parkland at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, where a 19-year-old shooter took the lives of 17 people and injured 17 others.96In Texas, even a full year after the shooting at Robb Elementary, political leaders have not taken any such action.

“I’m here today to be a voice for my son who was only 10,” said Felisha Martinez, the mother of Xavier Lopez, who was one of the children to lose their life last year in Uvalde, at a rally in Austin in 2022 in support of raising the minimum age requirement.97 “An 18-year-old was able to purchase a weapon to murder 19 children and two teachers. We need to do better and get these laws changed.”

Texas

This year, State Senator Gutierrez has introduced a package of bills designed to address gun violence in Texas, including Senate Bill 145, which would raise the minimum legal age for purchasing or renting a firearm from 18 to 21.98 This bill and others face an uphill climb without more support from the state’s Republican leaders. Governor Abbott expressed his views that an age restriction would violate the Second Amendment, ignoring the fact that similar constitutional challenges to Florida’s minimum age law, and those in other states, have not been successful.99

Texas House Speaker Dade Phelan has also publicly stated that this policy lacks the vote to pass. However, at the very least, Speaker Phelan should grant the opportunity for full debate and discussion of this policy and allow for a vote, so Texans can know which of their elected representatives oppose policies that could help prevent the next tragedy.

“Simply doing nothing is about as evil as it comes,” said Senator Gutierrez in the weeks following the shooting at Robb Elementary.100 Texas leaders must set politics aside and find the courage to protect their constituents.

Congress can also take action at a federal level and determine the minimum age of legal firearm purchase and possession. Currently, federal law applies differently depending on whether the seller is a licensed or unlicensed dealer and if the firearm in question is a handgun or long gun.101 Unlicensed dealers can sell a long gun to a person of any age, and can sell handguns to individuals 18 or older. Licensed dealers can sell long guns to individuals 18 or older and handguns to individuals 21 and older. Strengthening age restrictions nationwide would remove ambiguity and help prevent all-too-frequent acts of gun violence and self-harm committed by young people.

Passing an Extreme Risk Protection Order Law

Extreme risk protection orders (ERPOs) provide a proactive way to stop mass shootings and other tragedies by temporarily intervening to suspend a person’s access to firearms if they show clear warning signs of violence. An FBI study of the pre-attack behaviors of active shooters found that the average shooter displayed four to five observable and concerning behaviors over time, often related to the shooter’s mental health, problematic interpersonal interactions, or other signs of violent intentions.102

In many instances of gun violence, family members or friends noticed warning signs that people close to them were at significant risk of harming themselves or others. The shooter who perpetrated the 2018 school shooting in Parkland, Florida, for instance, was prohibited from carrying a backpack on school grounds for fear that he might be concealing guns. He had been the subject of dozens of 911 calls to local law enforcement and two tips to the FBI. Yet Florida at the time, as is the case now in Texas, lacked a mechanism of preventing him from accessing guns. Extreme risk protection laws fill this gap by empowering families, household members, and law enforcement agencies to petition courts for a civil (non-criminal) order to temporarily suspend a person’s access to firearms before they commit violence.

In response to an increasing number of tragedies, states have begun enacting lifesaving tools that can prevent gun tragedies before they occur, including in politically conservative states like Florida—unofficially known as the “Gunshine State” for its strong position in opposition to gun safety laws.103 Following the school shooting in Parkland, Florida enacted an extreme risk protection order law. This law created a process for courts to temporarily suspend a person’s ability to lawfully access firearms if the court determines there is sufficient evidence that the person presents a significant risk of violence or self-harm in the near future.

In response to this, the NRA responded by lowering the grades of any legislator who voted for the bill, including demoting then-Governor Scott from an A+ to a C. Yet this did not have any political consequences for Republican supporters of the bill. “Not one Republican who voted for that bill in Florida has paid a political price for protecting kids and doing the right thing.”104

Given the evidence that ERPOs can save lives and prevent tragedies, Texas legislators should show the same courage that Florida legislators did in 2018. Florida’s ERPO process has already been used thousands of times to temporarily disarm people showing clear warning signs of violence, including a man who put a loaded gun to his head in front of his girlfriend and his mother, a woman who threatened to burn down her house and shoot any responders, and a father who threatened to shoot everyone at his son’s school.

Studies further confirm the lifesaving benefits of this policy. Researchers found that one life was saved from suicide for every 10 firearm removals under Indiana’s extreme risk law. Studies of Connecticut’s law similarly found that by temporarily removing weapons from 762 high-risk individuals over the study period, Connecticut’s extreme risk law had prevented up to 100 suicide fatalities, in addition to lives saved from the prevention of homicide.105 Similarly, Connecticut’s and Indiana’s extreme risk laws have been shown to reduce firearm suicide rates in these states by 14% and 7.5%, respectively.106 A recent study of ERPOs use in six states reported 10% of ERPO petitions involved threats of mass violence: The threats targeted schools, businesses, intimate partners and their children, and families, and judges granted more than 80% of the petitions.

In the wake of a recent tragedy in Louisville, Kentucky’s Republican governor, Andy Beshear, called on state legislators to pass an ERPO law to help prevent future tragedies. “I’d like to think Democrats and Republicans—red or blue, anybody on the ideology—can come together and say, ‘If we know somebody is right on that brink of going out and committing a horrendous action, don’t you think we should be able to take action?’” he said.107 Governor Beshear is right, and Governor Abbott should follow this example and exhibit similar courage—the courage to place the lives of Texans above the special interests of the gun lobby.

Implementing Background Checks for All Gun Sales

A dangerous gap in our federal gun laws allows people to buy guns without passing a background check. Under current law, unlicensed sellers—people who sell guns online, at gun shows, or anywhere else without a federal dealer’s license—can transfer firearms without having to run any background check whatsoever.

Because of this loophole, people who are subject to domestic violence convictions or court orders, people who have been convicted of violent crimes, and people ineligible to possess firearms for mental health reasons can easily buy guns from unlicensed sellers with no background check in most states. In fact, an estimated 22% of US gun owners acquired their most recent firearm without a background check—which translates to millions of Americans acquiring millions of guns, no questions asked, each year.

Source

Matthew Miller, Lisa Hepburn & Deborah Azrael, “Firearm Acquisition Without Background Checks,” Annals of Internal Medicine 166, no. 4 (2017): 233–239.

Texas is one of 29 states that has not addressed this gap in federal law with its own state-level background check requirement. The state has no law requiring a background check on the purchaser of a firearm when the seller is not a licensed firearms dealer.108

This policy failure has had ongoing and deadly consequences. As just one example, a man fatally shot seven people and wounded 25 others in West Texas in 2019. The shooter previously failed a criminal background check when trying to purchase a gun, yet loopholes in national and Texas gun laws allowed him to bypass the background check system altogether and obtain the AR-style weapon used in his deadly attack from an unlicensed seller who wasn’t required by Texas law to run a background check.109

“Seventy-eight percent of Texas voters support strengthening background checks, recognizing that we must do more to keep guns out of the hands of individuals with dangerous histories,” states the Texas Gun Sense website.110 “This measure could have prevented the mobile mass shooting in Midland-Odessa.”

Research has shown that states which have closed the background check loophole through firearm owner licensing see a 56% reduction in mass shootings,111 proving that background checks have the potential to stop not only individual homicides and suicides, but also mass tragedies. Background check laws also help prevent guns from being diverted to the illegal gun market. States without universal background check laws export crime guns across state lines at a 30% higher rate than states that require background checks on all gun sales.112

In recent years, states like New Mexico,113 Virginia,114 and Vermont115 have responded to gun violence by enacting this commonsense, lifesaving measure. Governor Abbott and the leaders of the Texas legislature should do the same. This kind of system change would respect the Second Amendment rights of responsible gun owners while also honoring the 21 lives lost in Uvalde—and the countless lives impacted by gun violence across the state—with concrete action that will prevent similar tragedies from occurring in Texas in the years to come.

Expand Community-Based Programs and Services for At-Risk Youth and Young Adults

One of the most common needs expressed by Uvalde residents was the lack of programming, services, and safe spaces for youth, and particularly for youth that may be at higher risk of participating in violent behavior. “There are definitely not enough services in Uvalde for at-risk kids, we don’t even have a Boys & Girls Club,” noted members of one family whose daughter attended Robb Elementary and was there on the day of the shooting.116 “And there’s just zero for high-risk kids who have dropped out of school, like the shooter did.”

Expanding these services in Uvalde would help fill an important community need and also work to prevent future violence. An analysis of school shootings from 2008 to 2017 by the Secret Service showed that most school-age attackers have a number of common traits and circumstances, including a history of school discipline and a major source of social stress at least six months, such as bullying, romantic conflicts, or fights with family members.117 Many of these conditions were present for the Uvalde shooter, but there was not a system of support in place to help him address these issues.

“The constructive interventions may be counseling, support for education in a school setting, employment support, social services, these kinds of measures that are really intended to help a person improve their situation and thereby steer them away from thinking about potential violence,” said Mother Jones journalist Mark Follman, whose recent book Trigger Points discusses the need for behavioral health interventions that can stop mass shootings before they occur.118 “Often these are people who have deep grievances that they are having trouble letting go of, and they’re seeking a way out of a problem that they feel stuck in.”

Providing services to at-risk youth and young adults is not just a way to prevent a future mass shooting, but is also a protective factor against small-scale forms of violence and self-harm, helping to lower the risk of suicide. “In communities with stronger systems, those youth are often identified in the courts or at school for help before their problems turn into bigger issues,” pointed out an article in the Texas Tribune.119 “But in Uvalde, as with other underserved places, there are no formal mechanisms in place to do this. There are no automatic referrals to counselors for truancy, for example, or for alternative school placement.”

Such services have long been lacking in Uvalde, but now that the community has experienced the trauma of a horrific school shooting, the provision of support and programs for young people is more critical than ever. Community members reported that one of the most pressing gaps is the lack of a physical location where youth can participate in enriching activities.50 “Currently, the community has a limited number of local programs and youth activities,” noted a mental health assessment conducted by the Meadows Mental Health Policy Institute.7 “Uvalde [Consolidated Independent School District] leadership expressed a strong desire for the development of engagement opportunities for the community to come together around this shared experience to meet the needs of the school staff and families by providing a space for the overall community to move forward together.”

One of the efforts underway to help address this is the planned construction of a state-of-the-art multipurpose community center, which was supported with a $7.9 million investment by the Centene Charitable Foundation.82 In partnership with Community Health Development, Inc. (CHDI), a federally qualified health center, the vision for the space is to function as a one-stop resource for residents in Uvalde and the surrounding region. It would house health care providers, youth development programs, educational supports, retail space for local businesses, and a garden to honor the victims of the shooting at Robb Elementary.

“Six days after the horrific tragedy at the Robb Elementary School, Centene and Superior met with CHDI and local leaders to understand how we could best support Uvalde in what will necessarily be a long-term recovery,” said Sarah London, chief executive officer of Centene.20 “As that process continues, expanding the resources available to the entire community for physical, mental, and emotional health is an important step forward.”

The Uvalde Community Center is slated to be completed in 2024, and several stakeholders expressed enthusiasm about being able to host so many services in a single location—especially in a community where transportation remains a major obstacle. That said, there is still a pressing need to increase the availability of services in the short-term and to provide support for longer-term projects like the Uvalde Community Center.

Along these lines, the Meadows Report also includes a recommendation to implement “Youth Mobile Crisis Teams,” in the Uvalde region. These teams “specialize in working with youth and caregivers to de-escalate crises, provide limited in-home supports, and link the young person and family to appropriate ongoing services. They have a strong track record of diverting youth from inpatient placement and helping them remain in their community.”7 We echo that recommendation here, and call for the implementation of a range of other culturally response services for at-risk youth in the area.

State Investment in Community Violence Intervention Strategies

At the state and national levels, the tragedy in Uvalde highlights one of Texas’s—and America’s—most glaring gaps when it comes to the gun violence epidemic: the lack of services for high-risk youth. Far too often, especially in America’s most underserved communities, once a young person is outside the school system, there are no formal support systems to help address underlying risk factors for violence. In other words, those who are most in need of help are also those who are least likely to receive it, especially in a state that was recently ranked last in the nation in terms of access to mental health care64 and 45th when it comes to overall child well-being.120 This needs to change.

That said, Texas leaders must recognize that homicides and shootings are much, much more common in underserved communities of color and in physical locations other than schools: In 2020, 79% of the state’s 1,734 gun-related homicide victims were non-white, and almost all occurred somewhere other than a school campus.121 In the US, as in Texas, “Far more kids are shot outside school than in one—7,100 a year between 2012 and 2014 , or 19 every day, (compared with about 60 shootings at schools each year),” wrote David Ropeik, a retired instructor at Harvard and the author of a book on risk.122 “The statistical likelihood of any given public school student being killed by a gun, in school, on any given day since 1999 was roughly 1 in 614,000,000.”

This underscores the need to invest in programs specifically designed to reach individuals at high risk of engaging in violence in the areas most disproportionately impacted by violence—following the example of programs like Massachusetts’s Safe and Successful Youth Initiative (SSYI), which supports the local implementation of community-based services to reduce the risk for young people in both school and community settings.123 Studies have shown that with an annual investment of $10 million, SSYI is reducing instances of serious violence and creating huge savings for taxpayers as a result, creating more than $5.10 in savings for every dollar invested in the program.124

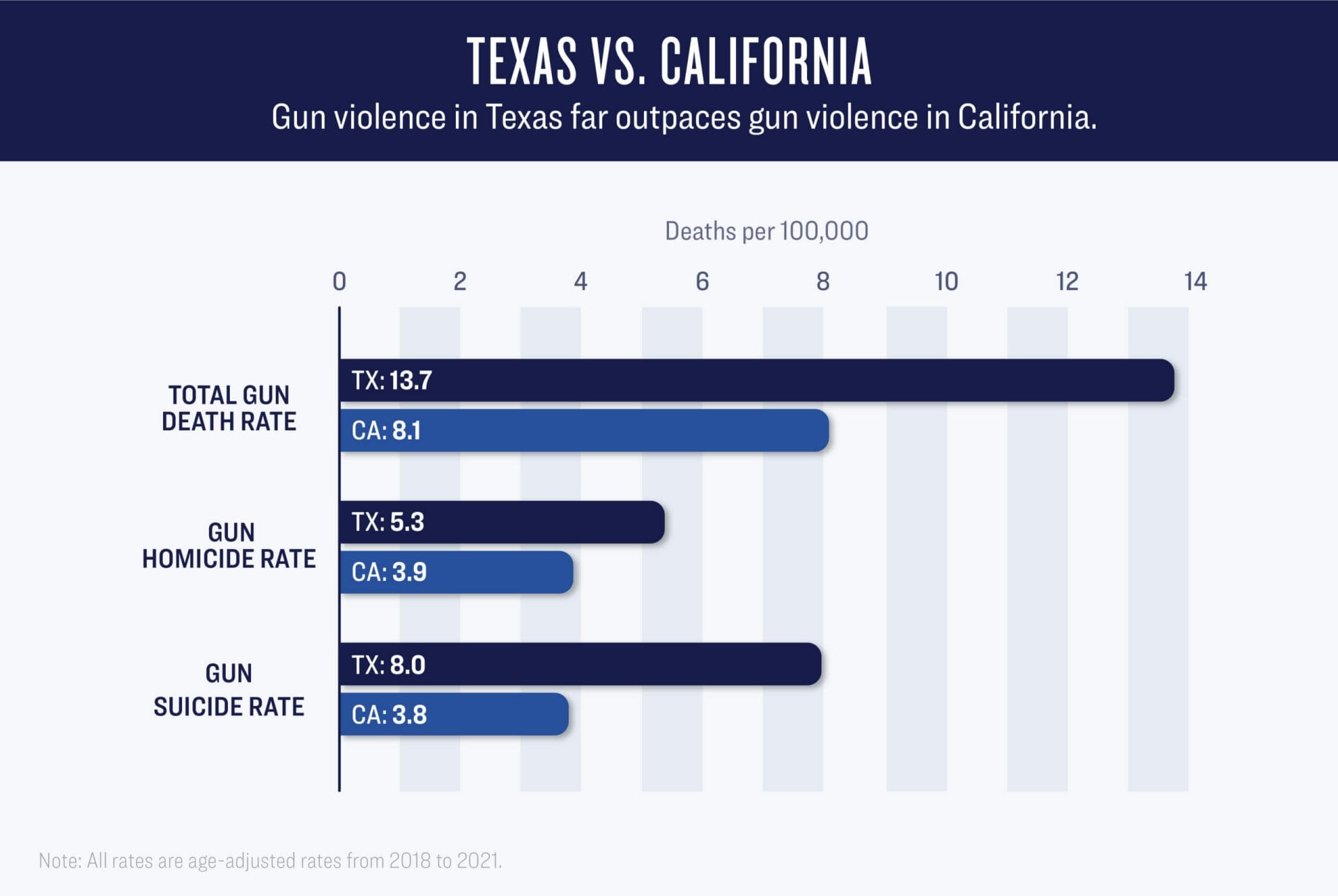

At present, Texas is not making any state-level investment in these kinds of CVI programs. It’s noteworthy that the gun homicide rate in Massachusetts is three times lower than in Texas. For context, Massachusetts is investing nearly $40 million annually for the types of programs described above, which represents a per-homicide investment of more than $260,000. A proportional investment in Texas would require an appropriation of $575 million.

Given the urgency of community violence, and the promising fiscal outlook in Texas—with a projected budget surplus of $32.7 billion125—now is the time for an effort to truly meet the moment. Texas should join the many other states that are taking significant action on this issue including Illinois ($250 million),126 California ($200 million),127 Wisconsin ($45 million),128 Pennsylvania ($30 million),129 and New Jersey ($10 million).130

Develop Long-Term Mental Health Services

Mass shootings tend to lay bare the most severe divisions and unmet needs that exist in a community even prior to the tragedy, and inadequate mental health resources are often at the top of the list. This is especially true in Uvalde, which before the shooting at Robb Elementary was described as a “mental health desert.” It doesn’t help that it’s in a state that ranks last in the nation in terms of per capita state spending on mental health and overall access to mental health care.119

In September 2022, Texas ranked last in the country when it came to the number of people insured, and 14% of children with health insurance in the state don’t have coverage for mental health services.60 The state also ranks 50th for the ratio of mental health providers to people, with only one provider for every 830 people.20 This lack of access to mental health services has and will continue to significantly hinder a Texas community’s ability to recover post-shooting.