Gun Violence in the US Territories

Introduction

Executive Summary

One of the shootings happened on the freeway.1 Another took place at a local community center, where a 17-year-old and three others were shot and killed. Over the course of one weekend, 18 people were shot and at least nine died.2

Two weekends later, a couple dozen miles away, there were two shootings: one at a shopping mall that injured four people and killed one, and another that ended with the arrest of the shooter, who was later charged with assault, reckless endangerment, and possession of an unlicensed firearm.3

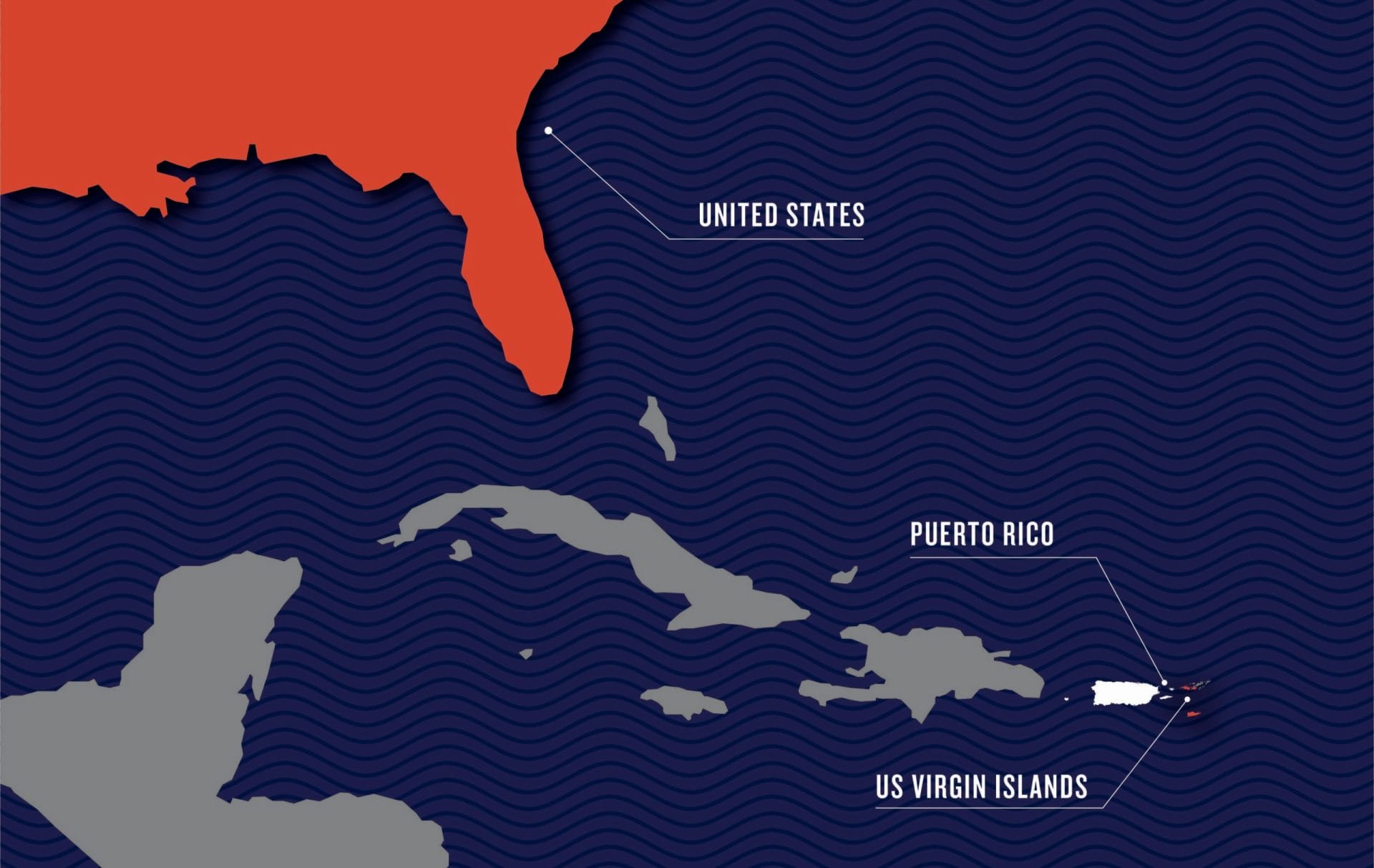

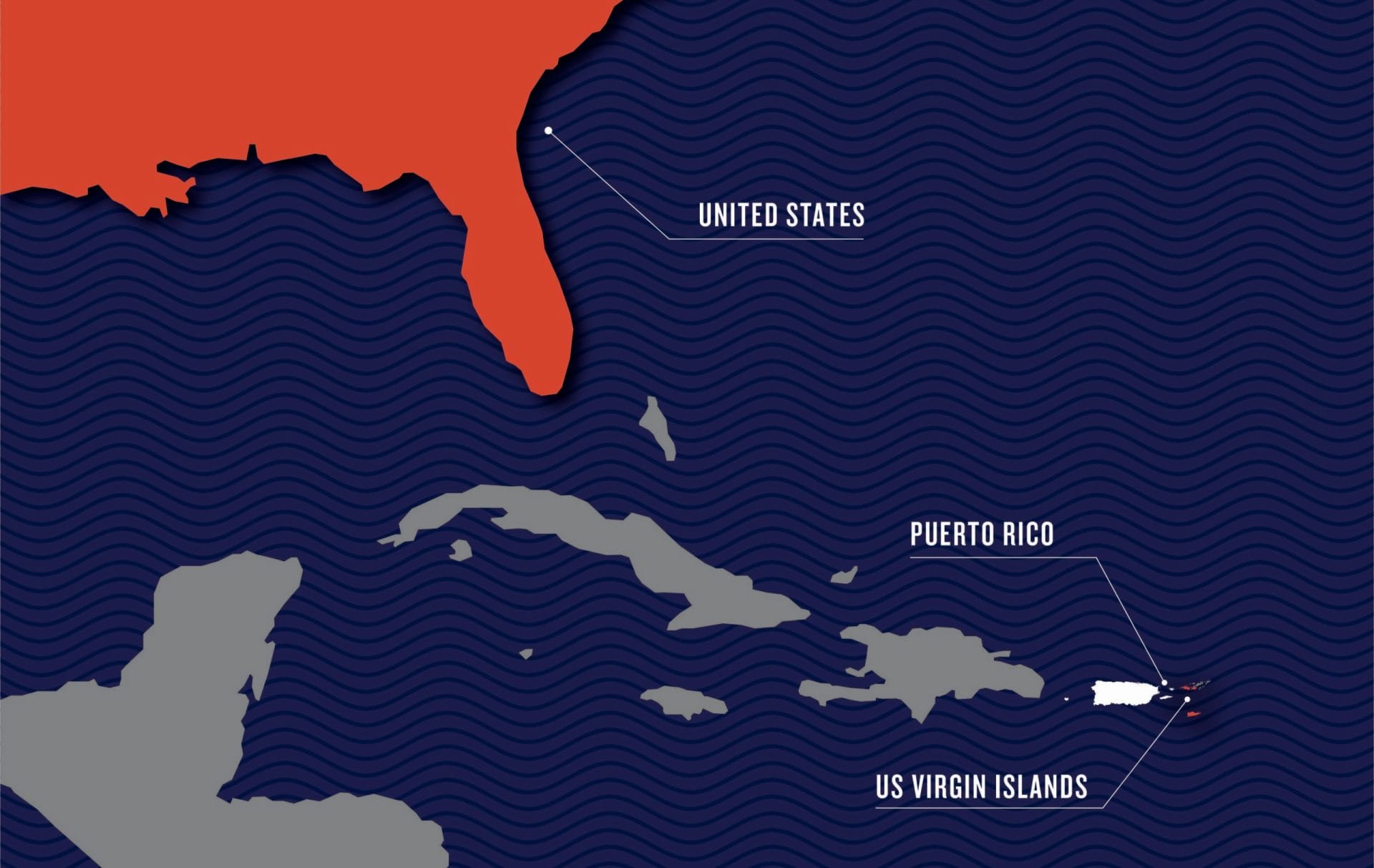

For many Americans, the stories of these two weekends are tragically familiar. News outlets in major US cities all too often document the body counts of bloody weekends marked by multiple tragic shootings. But gun violence doesn’t only happen in big cities. The stories of these two weekends happened in Puerto Rico and the US Virgin Islands—regions that experience some of the highest levels of gun violence in the United States, which often goes under-reported.

Gun violence is a uniquely American problem—and it’s only getting worse. Within the last 10 years, the firearm mortality rate has risen nearly 18%,4 with an average of 39,000 Americans dying from gun violence from 2015 to 2019.5 Over 45,000 Americans died from gun violence in 2020 alone, making it the deadliest year for gun violence in decades6—and projections for 2021 suggest that gun violence rates are even higher.7

The US firearm mortality rate is already strikingly high, more than 11 times higher than other high-income countries.8 The US also accounts for nearly 15% of all firearm deaths globally, despite only consisting of four percent of the world’s population.9 This growing epidemic has drawn much attention in the 50 states. But gun violence in the US territories rarely factors into the national conversation.

Gun violence has become all too common in Puerto Rico, where the firearm mortality rate was 1.7 times higher than that of the 50 states in 2018 (the last year for which data is available).10 The US Virgin Islands (USVI) also experience staggering levels of gun violence. In 2020, the archipelago11 saw a firearm homicide rate of 50 per 100,000,12 8.5 times the rate of the 50 states.13

Puerto Rico and the USVI are among two of the five permanently inhabited US territories, which also include the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI), Guam, and American Samoa. While Puerto Rico and the USVI see drastically high rates of gun violence, based on available data, the territories in the Pacific—Guam, CNMI, and American Samoa—seem to experience relatively low rates of gun violence.14

Puerto Rico and the USVI’s gun death rates outpace the rates of all 50 states, largely fueled by gun trafficking and the use of illegal firearms. In 2020, the USVI was the second leading importer of firearms recovered by law enforcement among all states and territories.15 In Puerto Rico, only 13% of firearms recovered by law enforcement in 2020 were sold there, whereas in the 50 states, on average, 66% of firearms recovered by law enforcement and traced by ATF were originally sold in that state.16

The problem of gun violence and gun trafficking in these places has long been neglected by politicians and advocates. This report attempts to shine a light on the growing gun violence epidemic in Puerto Rico and the USVI, and makes recommendations for how to address this crisis.

A Note on US Territories

Due to the historically colonial relationship between the federal government and the territories, some residents of these areas continue to refer to them as US colonies. Per guidance from the federal government, this report will use the term “territory” to describe all of these areas under US jurisdiction.17 Residents of these territories are American citizens, except for those in American Samoa.18 For clarity, this report will also use the phrase “50 states” to refer to the 50 states and Washington DC, but excluding the US territories.

Methodology

To determine the rate and number of gun deaths in the 50 states, researchers generally rely on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). However, the CDC does not publish data on gun deaths in the US territories. Therefore, to describe the extent of gun violence in both the 50 states and the territories, the figures in this report are sourced from a combination of academic research articles, the federal government, territorial governments, and locally collected data.

The lack of recent and consistent data in the USVI and Puerto Rico is the result of a number of factors. Both the USVI and Puerto Rico lack the funding to collect comprehensive mortality data, and some of the sources we looked at use different definitions for varying types of mortality.19 Additionally, Hurricane Maria in 2017 severely affected both territories’ ability to accurately collect mortality data.

To supplement the lack of reliable and/or up-to-date mortality data, we conducted interviews with stakeholders in both territories.20 For the USVI, we spoke to individuals who are currently in the federal government as well as former federal officials who worked in the islands. However, we could not identify other experts who work on the issue of gun violence prevention on the islands. For Puerto Rico, we spoke to a number of community members, researchers, and federal officials who have worked on gun violence prevention in some capacity.

These conversations helped us better understand the social, political, and historical contexts surrounding gun violence in the USVI and Puerto Rico, and they guided our efforts to describe the extent of gun violence in these two territories.

MEDIA REQUESTS

Our experts can speak to the full spectrum of gun violence prevention issues. Have a question? Email us at media@giffords.org.

Contact

US Virgin Islands

The USVI have been subjected to a number of colonial powers over the course of their history. The Dutch colonized the islands in the 1600s and used them as the center of trade, mainly involving sugar, tobacco, cotton, and rum. The Dutch slave trade also revolved around the Virgin Islands, and the majority of the population in the archipelago is descended from enslaved African people.

Eventually, the British and Spanish also colonized and took possession of parts of the Virgin Islands. The Dutch sold its share—which is now the US Virgin Islands—to the US in 1917 for $25 million in gold.21 Ten years later, the US granted citizenship to the residents of the USVI, and the territory gained self-governance through the Organic Act of 1936, forming its own government in 1954.22

Gun Laws in the USVI

A number of conditions make a person ineligible for a firearm license, including:28

- Prior conviction for a crime that carries a penalty of more than a year in prison

- Fugitive from justice status

- Addiction to controlled substances

- A determination by a court that the person has certain mental health conditions, or prior commitment to a mental health facility

- Undocumented immigration status

- Dishonorable discharge from the military

- Renounced citizenship

- Certain court-issued restraining orders

- Prior conviction for a misdemeanor domestic violence offense

In addition to the grounds for ineligibility, the commissioner cannot issue a license to those who have been convicted of an enumerated crime of violence29 or a violation of any “narcotic or ‘harmful drug’ law”; those who have severe mental illness;30 those who are addicted to alcohol, narcotics, or other drugs; or those who have violated the Virgin Islands’s gun laws in the past.31 USVI law also instructs the commissioner against issuing a license to a person “who for justifiable reasons is deemed to be an improper person by the Commissioner.”32

The Virgin Islands limits the carrying of firearms to those doing so pursuant to official duties, including members of the armed services, federal officers, certain federal contractors, law enforcement, and correctional officers, or to those who have been issued a carry license.33

To carry a concealed handgun on a 24-hour basis, an applicant must show one of the following:34

- Experience with a firearm through participation in organized shooting competitions or current military service

- That the applicant is a certified firearm instructor

- Proof of an honorable discharge from a branch of the US Armed Forces reflecting firearm qualifications obtained within 10 years of the application or that the applicant is a retired law enforcement officer with a USVI law enforcement agency

- Completion of handgun training within the last 10 years

Evaluations of laws in the 50 states with similar requirements for the possession and carrying of firearms were found to be associated with reductions in gun homicides.35However, the gun laws in the archipelago have been undercut by the high rates of illegal gun trafficking. Research has shown that states with stronger gun laws are more likely to be the destination of crime-related firearms trafficked from states with weaker gun laws.36 As discussed later in the report, a large proportion of firearms recovered by law enforcement in the USVI were originally sold outside the territory, which contributes to the high rates of gun violence the territory sees.

State of Gun Violence in the USVI

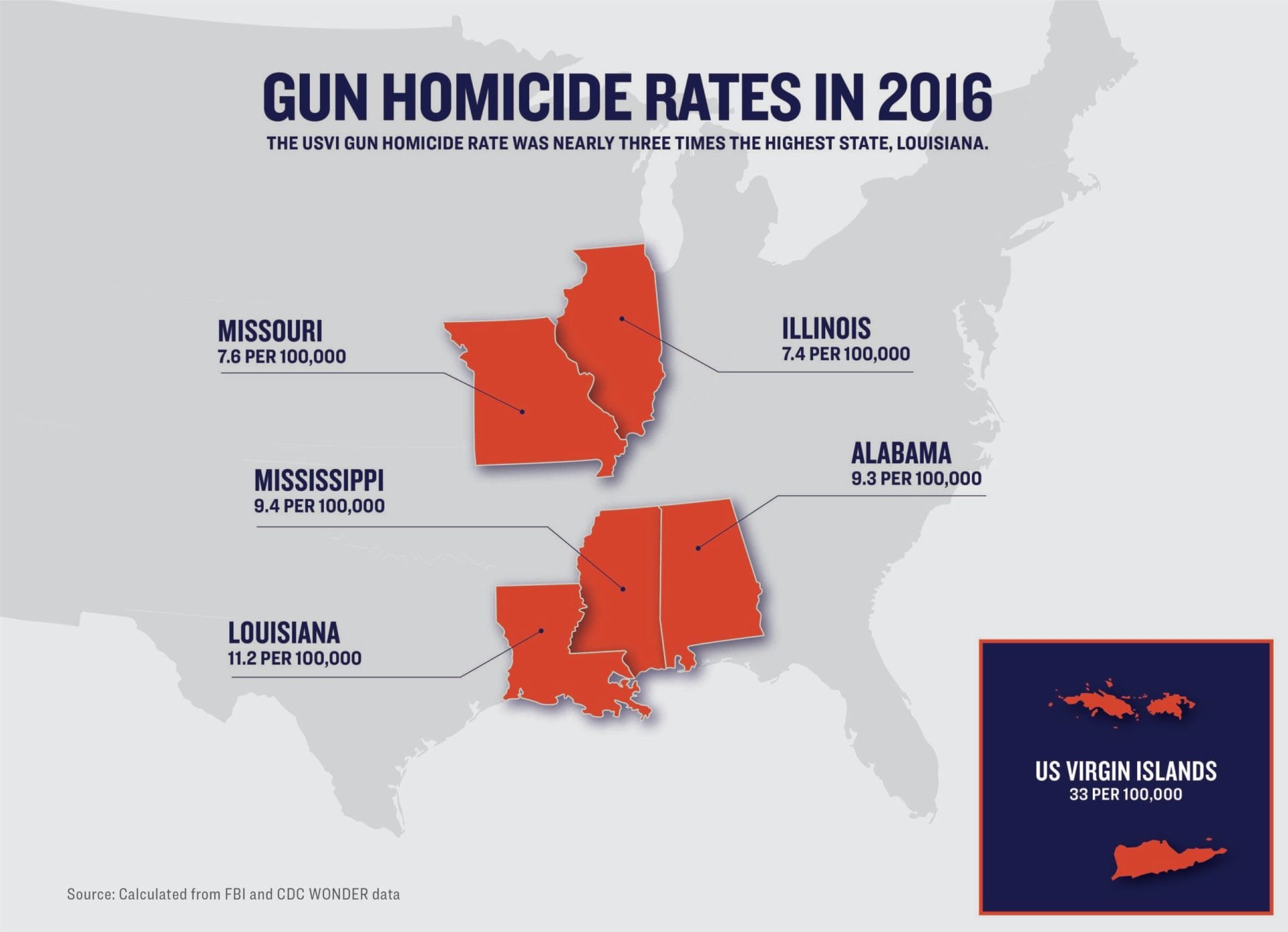

Gun violence is an urgent issue in the USVI. Researchers estimate that gun violence increased nearly 19% from 1990 to 2016.37 In 2016, the USVI gun homicide rate was seven times the rate of the 50 states.38 The same year, the USVI had a higher gun death rate than any state—more than triple that of Louisiana, which has the highest rate in the 50 states.39

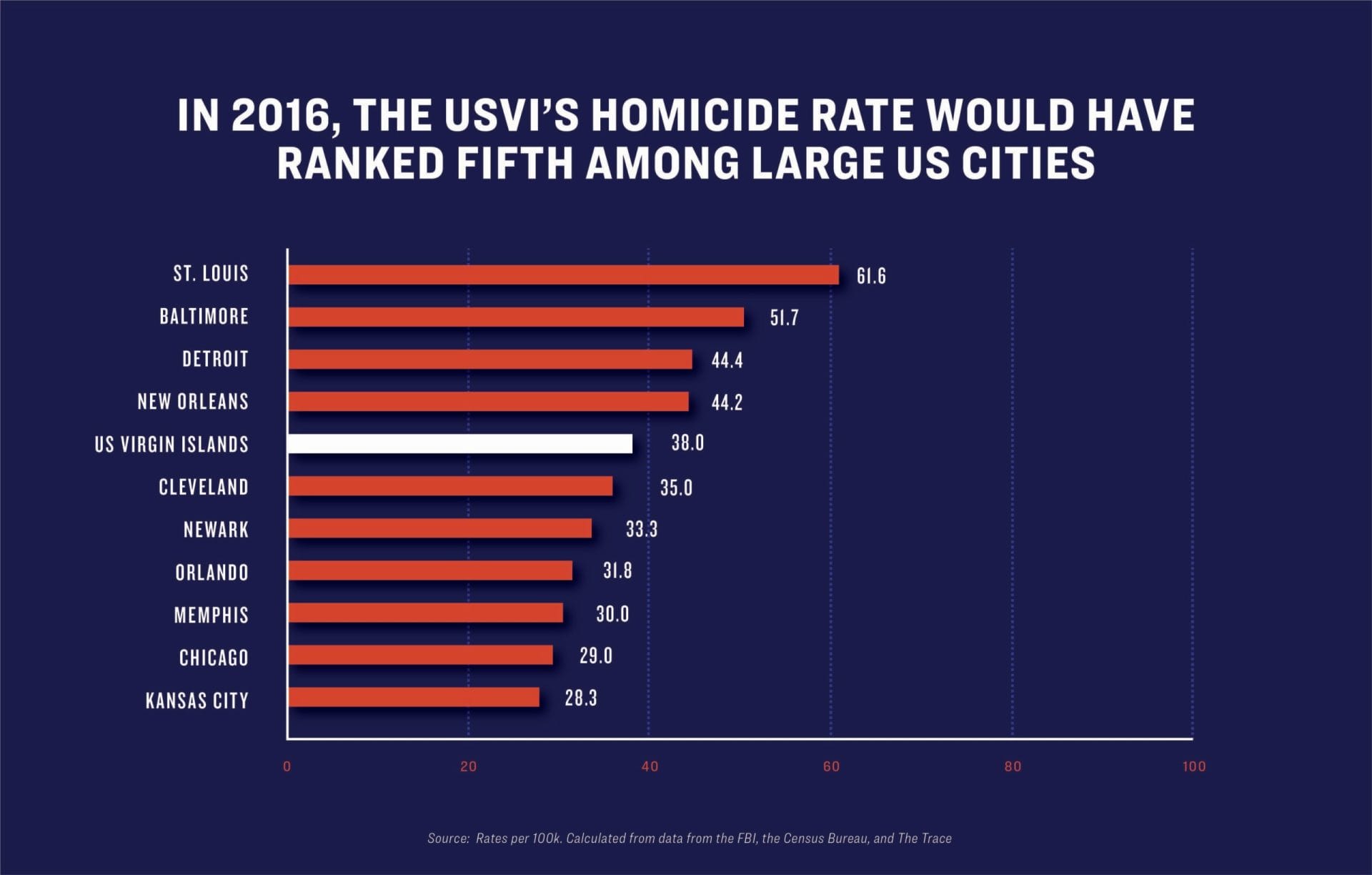

Gun violence tends to cluster in urban areas. In 2016, cities like St. Louis and Baltimore had gun homicide rates that were as much as four or five times the national rate. Gun violence rates in the USVI are comparable to those of major US cities—if ranked among large US cities, the USVI would have had the fifth highest total homicide rate in 2016.40

The most recent year of reliable data, collected by the FBI, was 2016, which saw 34 gun homicides in the USVI.41 Reporting from a local newspaper, the St. Thomas Source, indicated that nearly 98% of homicides in 2020 were gun homicides.42 In 2021, 93% of all tracked homicides involved a gun.43 While these figures may be an undercount, they suggest a crude gun homicide rate of at least 48 gun homicides per 100,000 residents.44 We did not find a reliable source of data on other types of gun violence, including nonfatal shootings and gun suicides.

Gun Trafficking in the USVI

On March 22, 2021, the US Attorney for the District of the Virgin Islands announced an indictment of a St. Croix couple who allegedly trafficked over 100 illegally manufactured firearms and sold them throughout the USVI.45 The couple allegedly ordered $60,000 worth of gun parts and accessories from companies in North Carolina and Florida and shipped the orders to various post office boxes in St. Croix. In the USVI, they assembled the firearms and sold them with the expectation that the guns would not be registered with the USVI Police Department, as required by law.46

Source

Erik J. Olson, et al., “American Firearm Homicides: The Impact of Your Neighbors,” Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 86, no. 5 (2019): 797–802.

The case of the St. Croix couple is just one of nearly a dozen firearm trafficking cases brought in the USVI since 2016. Various indicators—including ATF data, local media reports, and conversations with experts—suggest that gun violence in the USVI is fueled in large part by firearms imported from the US mainland.

According to ATF firearms source and recovery data, a high rate of guns are imported into the USVI. In 2020, 89% of firearms recovered by law enforcement were originally purchased outside the territory, the second highest import rate among all states and territories.15

The USVI sees high rates of firearms trafficking partly due to low legal gun buying within the territory. In 2020, states with universal background checks had, on average, approximately three times the rate of background checks compared to the USVI.47

The USVI has the lowest rate of legal gun buying among all states and territories.48 Among guns recovered by law enforcement, only 18% of all firearms recovered were originally sold in the USVI.49 Comparatively, 66% of all firearms recovered by law enforcement and traced by ATF were recovered in the same state in which they were originally sold.32

Local media is acutely aware of the problem of gun trafficking in the USVI, with the Virgin Island Daily News stating that the “ongoing influx of illegal firearms” has become a “chronic problem.”50 As drug and firearm trafficking are closely linked in the USVI, Congresswoman Stacey Plaskett, the non-voting representative from the USVI, has publicly pointed to drug trafficking as a reason behind the recent rise in gun violence.51

In interviews with Giffords Law Center, two former federal agents also identified gun trafficking as a contributing factor to the high rates of gun violence and described how illicit materials, including guns and drugs, come into the territory through the mail, on planes, and via ships and boats.52

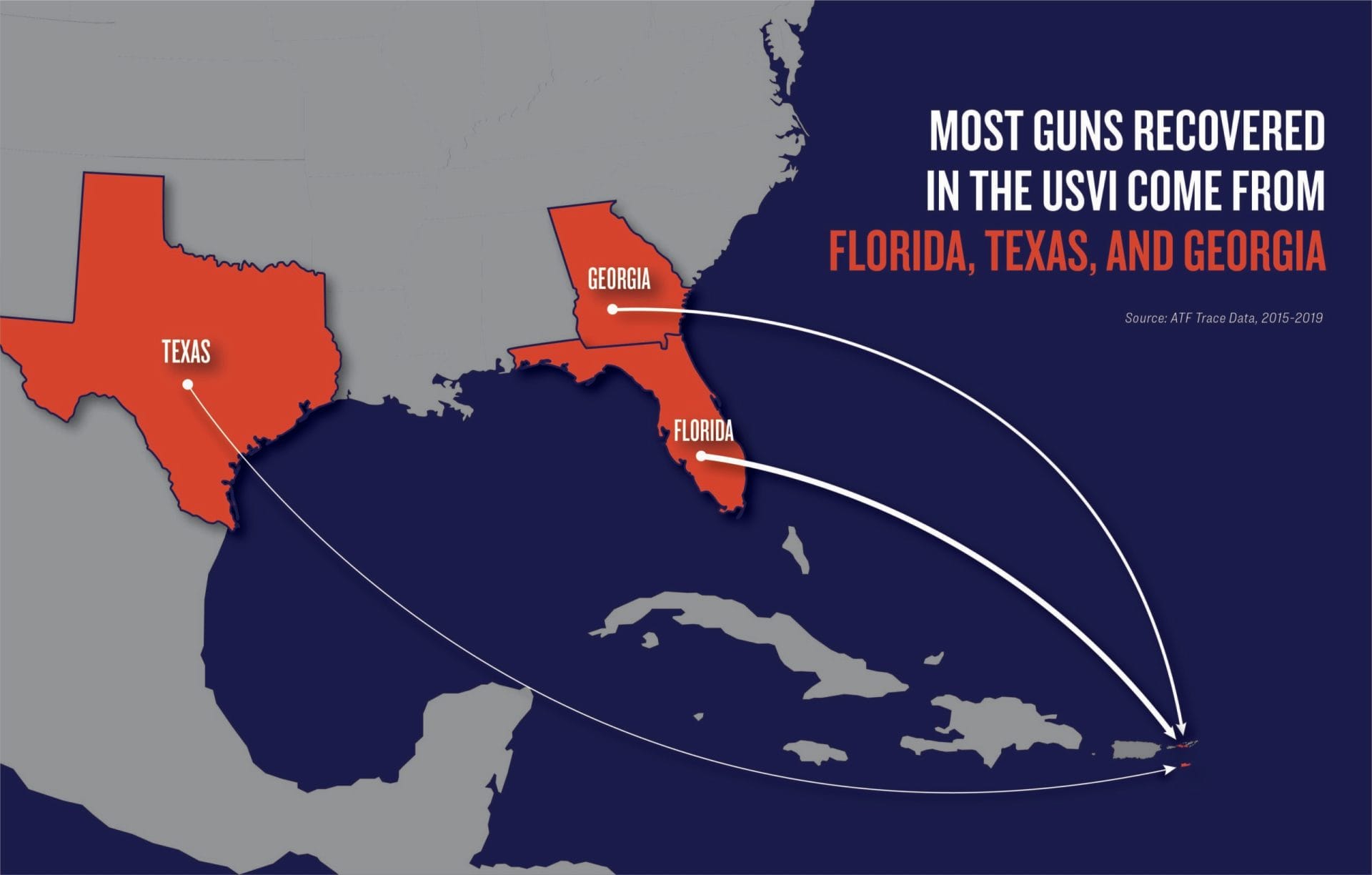

Analysis of guns recovered in the USVI supports what stakeholders told us about gun trafficking in the USVI. From 2015 to 2019, ATF recovered an average of 128 guns annually in the USVI.53 Many of the guns recovered in the USVI originated in the Southeast US, with around one-quarter (26%) purchased in Florida, the most common purchase source state.54

Georgia ranked second, accounting for eight percent of all guns recovered,32 and Texas ranked third, accounting for five percent of all guns recovered.32 Florida, Georgia, and Texas all have extremely lax gun laws, scoring a C-, F, and F, respectively, on Giffords Law Center’s Annual Gun Law Scorecard.55 Overall, more than 40% of guns recovered in the USVI were purchased within the last three years.56 Taken together, these metrics are strong indicators of gun trafficking.57

Efforts to Address Gun Violence in the US Virgin Islands

In 2020, the US Department of Justice (DOJ) announced two initiatives to prevent crime and gun violence on the islands: Project Guardian and Project Safe Neighborhoods.58 Both initiatives are expansions of national programs that have been touted as successful by the DOJ. Project Guardian launched in November 2019 as an enforcement-focused effort to address gun violence. The program involves increased coordination across government for prosecutions, information sharing, responses to blocked firearm transfers because of mental health issues, and crime gun intelligence. It also emphasizes prioritizing prosecutions for efforts to circumvent the federal background check system.59

Project Safe Neighborhoods is a violent crime reduction initiative effort first launched in 2001. As described in a previous Giffords Law Center report, Project Safe Neighborhoods is a nationwide grant program that has often supported harsh suppression efforts over the past two decades. In the 50 states, the program has led to skyrocketing gun possession prosecution with no demonstrable increase in public safety. Recent guidance by the Biden-Harris administration represents an attempt to direct Project Safe Neighborhood funds to community-based, non-punitive strategies.

The USVI police department’s website lists the goals of the Project Safe Neighborhoods initiative as lowering rates of gun violence, increasing community cooperation to address gun-related crime, utilizing swift and certain punishment, and promoting gun safety and education.60

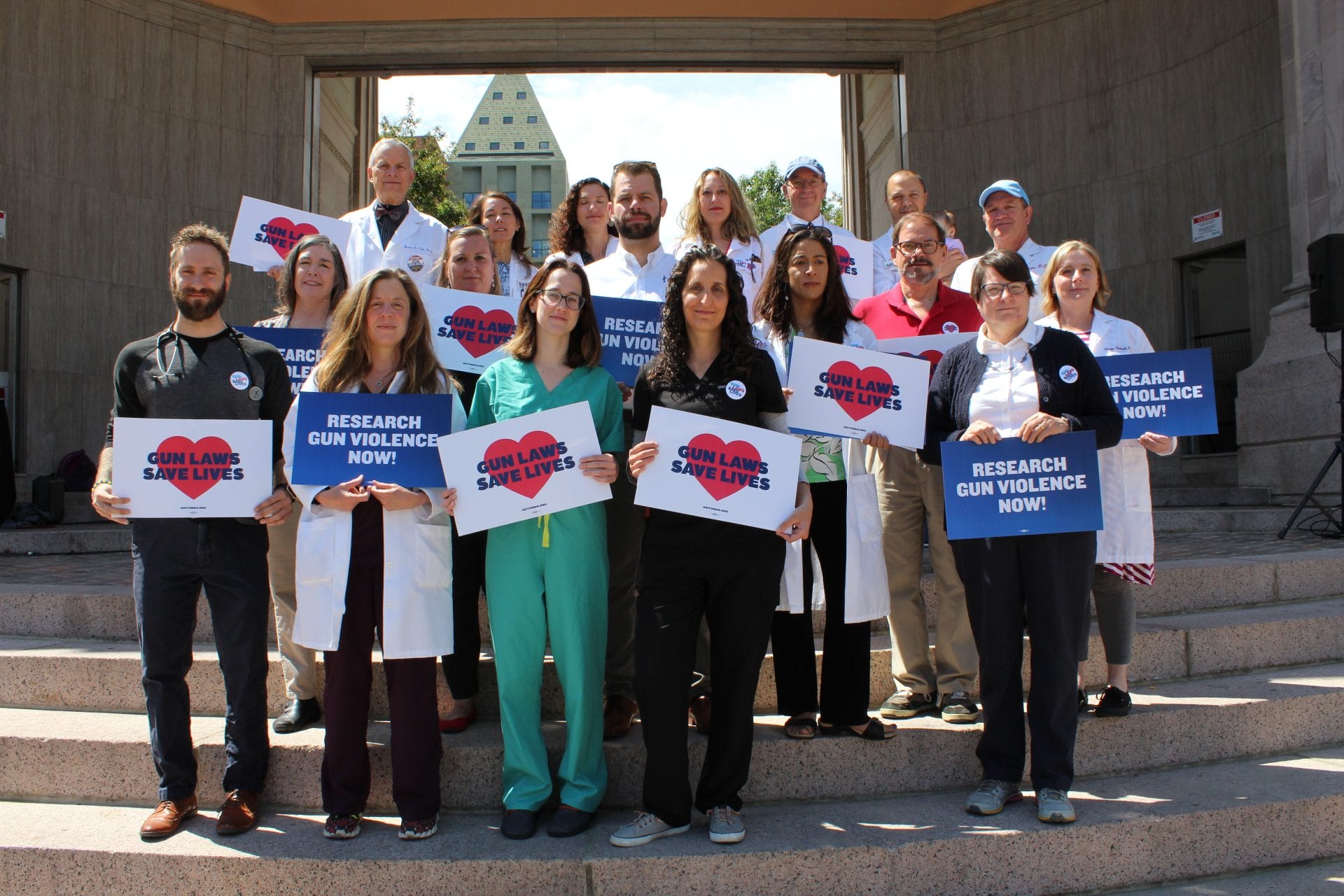

SUPPORT GUN SAFETY

We’re in this together. To build a safer America—one where children and parents in every neighborhood can learn, play, work, and worship without fear of gun violence—we need you standing beside us in this fight.

Puerto Rico

Like the USVI, colonialism shapes much of Puerto Rico’s history. Christopher Columbus arrived in Puerto Rico in 1493 and Spain colonized the archipelago shortly thereafter.61 After decades of colonization, Spain granted Puerto Ricans representation in Spanish courts and political participation in 1897.62

However, the conclusion of the Spanish-American War changed the colonial power in Puerto Rico. In 1898, the Treaty of Paris transferred power over Puerto Rico, Cuba, the Philippines, and Guam to the United States.63 Immediately afterwards, the US invaded Puerto Rico, and since then, Puerto Rico has been under American control. While under US control, Puerto Rico has been subjected to varying levels of autonomy. The US granted Puerto Ricans citizenship through the Jones-Shafroth Act in March 1917, making Puerto Ricans eligible for the draft. The US joined World War I one month later.64

The archipelago became a US commonwealth in 1952, which granted Puerto Rico the level of autonomy it currently possesses.65 After becoming a commonwealth, the population of Puerto Rico grew by over one million people, a nearly 50% increase. However, since reaching a peak of 3.8 million people in 2000,66 its population has steadily declined. Due to Hurricane Maria in 2017, as well as other events, roughly 3.3 million people currently live in Puerto Rico, a 15% decrease from 2010.32 Residents of Puerto Rico cannot vote in presidential elections, nor can the elected representative from Puerto Rico vote on legislation in the House of Representatives.

Gun Laws in Puerto Rico

Throughout its history, Puerto Rico has enacted very strong gun laws, some of which were stronger than the laws in any of the states. Like the 50 states, Puerto Rico is also subject to federal gun laws. Prior to 2020, in order to obtain a gun, Puerto Ricans had to obtain three affidavits for a license, get fingerprinted, belong to a gun club, and pay a fee of $125. They also had to take a gun safety course within 45 days of obtaining a license. To legally carry a concealed weapon on the archipelago, Puerto Ricans had to pay up to $1,000 and petition the courts for the right.67

The Case for Firearm Licensing

Apr 23, 2020

Studies of similar policies in US states have been found to be remarkably effective in preventing gun violence. However, in the last few years, the NRA began to organize residents and activists to lobby for a new, more lenient law.

In 2019, Puerto Rico enacted such a law: the “Ley de Armas de Puerto Rico de 2020,” or Puerto Rico Weapons Act of 2020, which significantly weakened Puerto Rican gun law. Prior to the new law, residents had to obtain separate licenses, one for purchasing and one for possession. Under this new law, Puerto Rico allows its residents to have one permit to purchase, possess, carry, and/or operate a firearm or ammunition.68 The new application process is also considerably less comprehensive, eliminating prior requirements that applicants submit character and fitness references and demonstrate that they feared for their safety.

Under the new law, firearms licenses are issued by the Firearms Licensing Office on a “shall issue” basis. Puerto Rico law provides that the Firearms Licensing Office shall issue a license to an applicant who satisfies the following requirements:69

- Is at least 21 years old

- Has never been convicted of, nor have pending charges of, a felony, attempted felony, misdemeanor involving violence, domestic abuse, stalking, or child abuse70

- Is not addicted to controlled substances or alcohol

- Has not been declared mentally incompetent by a court

- Has not been dishonorably discharged from the military or Puerto Rico Police Bureau

- Has not engaged in acts or been a member of an organization to overthrow the government

- Has not been subject to a court order within the last twelve months prohibiting stalking, harassing, threatening, or approaching any person, including a domestic partner or family member

- Is a US citizen or lawful resident

- Is not subject to firearm prohibitions under the federal Gun Control Act of 1968

In addition, applicants for a firearms license must complete training on firearms operation and handling through a course approved by the Puerto Rico Police Bureau.71 Furthermore, under this new law, any individual who already possesses a license to possess firearms (a “licensia de armas,” or firearms license) is automatically allowed to carry a concealed firearm, without having to obtain a separate carry license.72 Under current Puerto Rican law, holders of a firearms license may only carry one loaded firearm at a time, and the firearm must be concealed.73 Open carry is generally prohibited, except by law enforcement and other authorized individuals.74

Following these changes, the number of background checks for firearm purchases in Puerto Rico increased 134% from 2020 to 2021.75 While Puerto Rico’s new law is stronger than the gun safety laws of many states, high rates of firearms trafficking into the archipelago undermine the law and fuels the soaring rates of gun violence that vastly exceed the gun death rate of the 50 states.

The State of Gun Violence in Puerto Rico

Since 2000, Puerto Rico has suffered at least 600 homicides per year, with a peak of over 1,000 homicides each year between 2010 and 2012.76 In most years, gun homicides account for at least 80% of all homicides.46 In comparison to the 50 states, Puerto Rico’s rates of gun homicides are among the highest. However, a lack of reliable, consistent, and available mortality data sources has made it difficult to understand the historical and contemporary extent of gun violence in the commonwealth.

There have been many efforts to describe mortality and violence in Puerto Rico. Each source available covered slightly different time periods and used slightly different definitions for each type of mortality. Additionally, since Hurricane Maria hit Puerto Rico in 2017, researchers have struggled to count not only the number of people currently living on the archipelago but also the number of deaths as a result of the hurricane.77

This report relies on data from the Puerto Rico Violent Death Reporting System (PRVDRS) since it provides the most recent, detailed mortality data and was the closest to the CDC’s definitions and practices for monitoring gun deaths. An extension of the National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS), the PRVDRS has been working with the Puerto Rico police department, local health departments, and the Institute of Forensic Sciences since 2015 to coordinate and collect all data relating to violent deaths.78

While Puerto Rico has one of the highest gun violence rates in the US, gun violence follows a unique pattern on the archipelago.79 In the 50 states, 60% of gun deaths are gun suicides. The gun suicide rate in Puerto Rico is very low, making up just a fraction of overall gun deaths. In fact, the Puerto Rico gun suicide rate is five times lower than the average rate among the 50 states.80 However, the gun suicide rate has been on the rise in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria.81 According to the PRVDRS, the firearm suicide rate increased 26% from 2017 to 2018.82

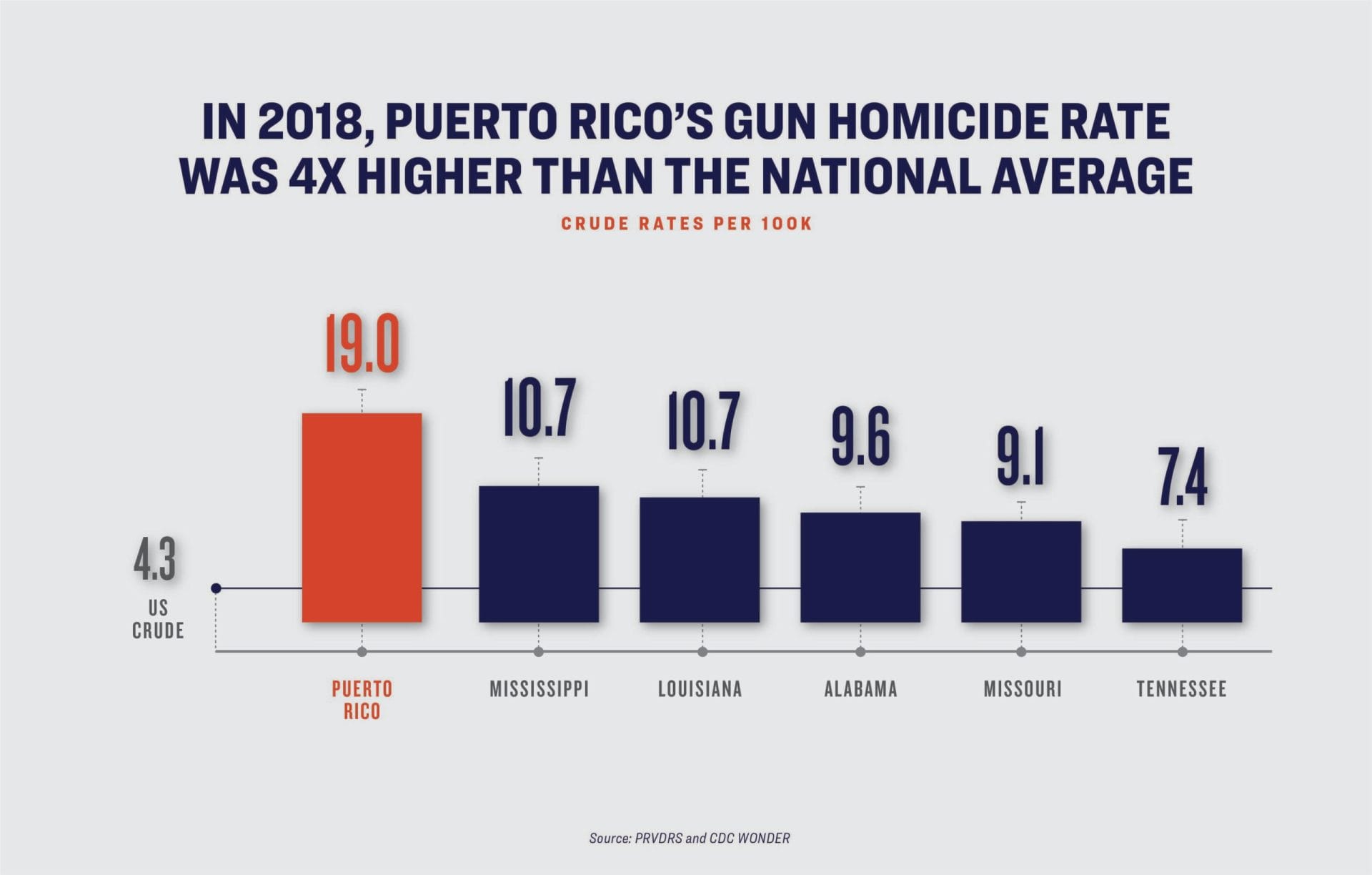

In contrast to its gun suicide rate, Puerto Rico’s gun homicide rate in 2018 was higher than that of any of the 50 states. The rate of 19.01 gun homicides per 100,000 was four times the national average.83Many experts we talked to confirmed that, similar to patterns in the 50 states, gun homicides in the archipelago concentrate in dense, urban areas.

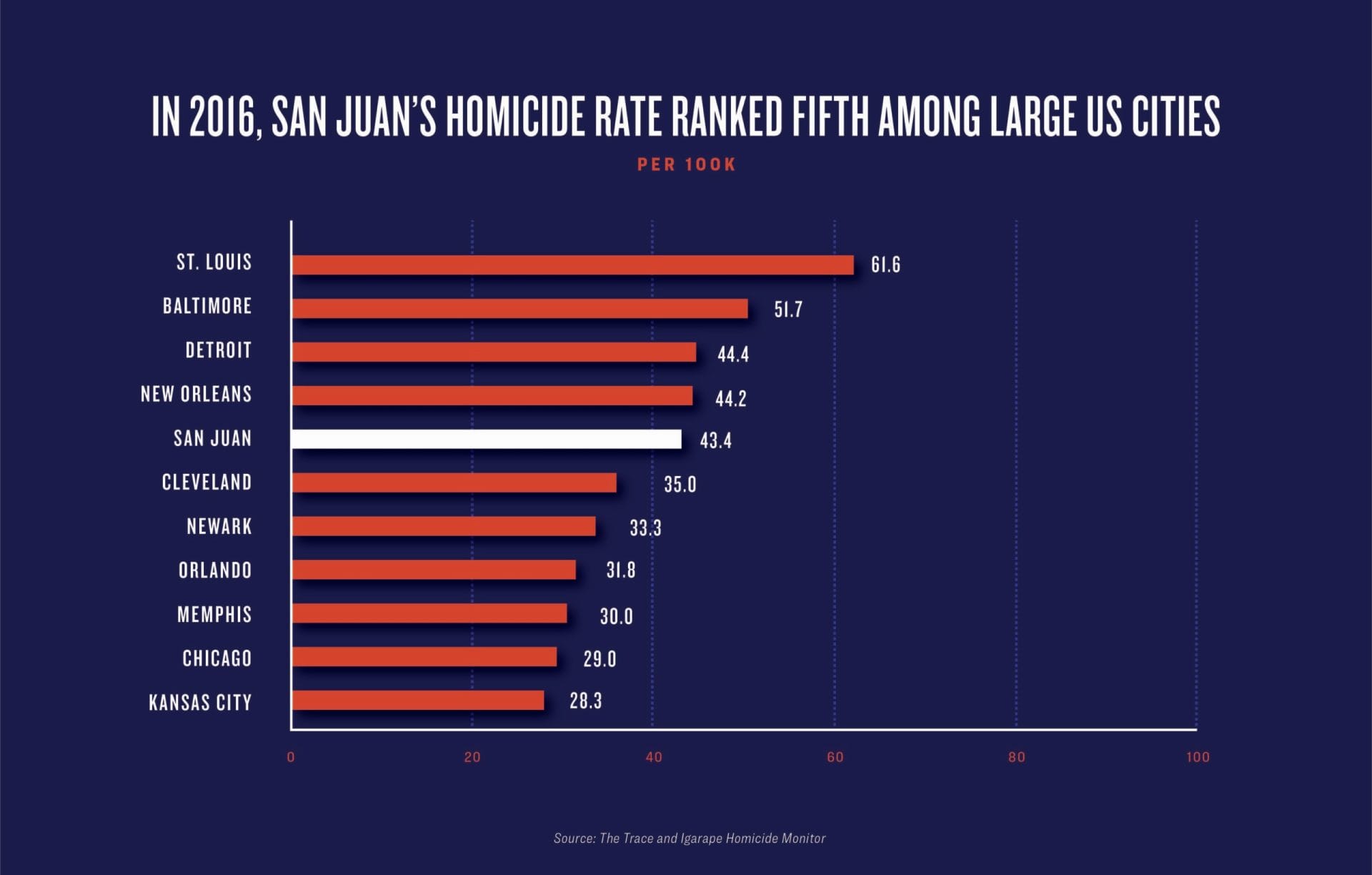

According to one study, homicides are concentrated in the metropolitan areas surrounding the capital of San Juan and the other major city, Ponce.84 In 2016, San Juan’s homicide rate was more than double the homicide rate for all of Puerto Rico.76 Compared to major US cities, San Juan had the fifth highest homicide rate.85

Gender-based violence has also drawn a considerable amount of attention in the archipelago. In 2018, the PRVDRS reported that women accounted for roughly eight percent of all violent homicide victims.86 In 2020, the Puerto Rico police department reported 5,517 incidents of domestic violence targeting women—over five times the number of such incidents targeting men.87 Additionally, one tracker found that Puerto Rico had the most trans deaths of any US state or territory in 2020.88

Due to heavy local media coverage of homicides targeting women and trans individuals, in 2021 Governor Pedro Pierluisi declared a state of emergency related to gender-based violence.89 Under the authority of the state of emergency, the governor has created a committee of representatives from multiple state agencies to research and address the problems. According to staff at the feminist organization Taller Salud, the committee has so far created protocols to help victims of gendered violence and continues to work on other solutions.

Driving Factors of Gun Violence in Puerto Rico

For years, Puerto Rico’s gun violence epidemic has largely gone unnoticed and unaddressed. While the laws outlined above attempt to regulate gun possession in the archipelago, two main factors, gun trafficking and corrupt policing, have exacerbated the problem. In addition, the failure of the US government to adequately fund programs to track and prevent gun violence in Puerto Rico must be remedied as soon as possible.

Gun Trafficking in Puerto Rico

On February 9, 2018, the US Attorney for the District of Puerto Rico announced the indictment of three individuals alleged to have trafficked ammunition and at least 16 firearms over the course of the first six months of 2017.90 The individuals had purchased the firearms and ammunition in Florida, transported them to Puerto Rico, and sold them across the archipelago. The trio sold various pistols, rifles, and ammunition of multiple calibers for a total of $47,300.

What’s Fueling Mexican Violence? American Guns

—Oct 30, 2019

This case is just one of at least 14 gun trafficking indictments made by the US Attorney for Puerto Rico since 2017. As with the USVI, rates of legal gun purchasing are low relative to the 50 states. A combination of these low rates, conversations with experts in Puerto Rico, and ATF recovery data indicates that firearms trafficking plays a substantial role in the high rates of gun violence in Puerto Rico.

Prior to the enactment of the 2020 law, it was fairly difficult to legally purchase a firearm. For instance, there are currently only two federal firearms licensees (FFLs) for every 100,000 residents in Puerto Rico—the lowest rate among the 50 states.91 States with universal background checks had, on average, approximately six times the rate of background checks compared to Puerto Rico.92

As in the USVI, the majority of firearms recovered by law enforcement were not originally sold in the archipelago. Only 13% of firearms recovered in Puerto Rico were sold there, compared to an average of 66% of all firearms recovered by law enforcement and traced by ATF in the mainland United States.16 Puerto Rico ranks second to last among all jurisdictions tracked by ATF in the percentage of guns recovered from law enforcement that originate within the jurisdiction.

Based on research and conversation with experts—including an assistant US attorney and two former federal agents, all of whom worked on or currently work on gun trafficking cases in Puerto Rico—most of the guns coming into the archipelago do so via mail or commercial airline flights. Due to its status as a commonwealth of the United States, people and packages are relatively free to flow from the mainland US to Puerto Rico.

People are able to purchase firearms in the 50 states—often in states with weak gun laws—and put them into packages to mail to Puerto Rico. One expert told us that Glock firearms are the most common gun trafficked because they can be easily converted into automatic weapons once they arrive.

While the US Postal Service has postal inspectors meant to stop the flow of illicit goods, including guns, into Puerto Rico, the Postal Inspector Service remains severely understaffed. One expert noted that because Puerto Rico is treated like a colony of the United States, the federal government does not provide an equal or equitable investment in preventing the trafficking of illicit goods.

Gun trafficking through commercial airline flights is similarly simple: an individual can easily buy firearms on the mainland, check luggage containing the firearms, declare the presence of the firearms to the airline, and fly to Puerto Rico. According to the former federal agents we spoke to, airlines are not required to alert law enforcement of the presence of firearms on their flights.

According to data collected by ATF from 2015 to 2019, the agency recovered and traced an average of 845 guns in Puerto Rico annually for which it could identify the purchase origins. Just as with the USVI, nearly 30% of all guns recovered during this time period were purchased in Florida, the most common purchase state. Texas ranked second, accounting for nearly 24% of all guns recovered. Ohio ranked third, accounting for nearly two percent of all guns recovered. Finally, Georgia ranked fourth accounting for close to one percent of all guns recovered. All four states have substantially weaker gun laws, making it easier for traffickers to purchase guns in these states—Giffords Law Center’s Annual Gun Scorecard rated Florida, Texas, Ohio, and Georgia a C-, F, D, and F, respectively.

In addition to the flow of trafficked firearms into Puerto Rico, one expert pointed to guns that can be assembled from parts, also known as ghost guns, as another concern. These guns or gun parts require the user to finish the assembly of the gun, often through an easy-to-follow kit that can be purchased online. Because these guns are not sold by a federal firearm licensee, they do not have serial numbers and cannot be traced, making them of particular interest to gun traffickers and other criminals. While data on the prevalence of these weapons in the territory is unknown, these weapons have increasingly been used in crime throughout the 50 states and represent a serious threat to a region already plagued by trafficking and gun violence.

Policing in Puerto Rico

According to federal prosecutors, in 2018 a Puerto Rico police officer illegally sold her service weapon and a weapon she had stolen from evidence. She then filed false police reports claiming her service weapon had been stolen from her residence and that the weapon from evidence had been stolen from her locker.93

Corruption along these lines is just one example of the problems with policing in Puerto Rico. Based on conversations with stakeholders in the archipelago and the history of police violence and extreme misconduct there, it seems clear that the majority of Puerto Ricans lack trust in the police to protect or serve. This leads to residents feeling unsafe and high rates of violence, including gun violence.

Source

“National Trends,” <i> Mapping Police Violence<i>, last accessed, May 1, 2024, https://mappingpoliceviolence.squarespace.com/nationaltrends.

Scholar Marisol LeBrón traces much of the modern mistrust of the police to tough-on-crime policies during the early 1990s. During the late 1980s and early 1990s, Puerto Rico experienced a large increase in crime. This rise in crime and violence prompted a new policy of “mano dura contra el crimen” or “iron first against crime.”94 These mano dura policies doubled down on draconian policing tactics that contributed to the racialization and social construction of specific communities and neighborhoods as crime-ridden and dilapidated.

One of the hallmarks of these policies was an executive order signed in 1992 by then-governor Pedro Roselló. The order deployed the National Guard into housing complexes where predominantly poor and Black residents lived.95 These residents suffered under the oppressive watch and control of the National Guard, which acted in concert with the archipelago’s police force.

These initiatives not only “fostered an environment of police brutality” but also “tacitly allow[ed] the proliferation of violence within economically and racially marginalized communities,” according to LeBrón.96In fact, in the two years after these tough-on-crime policies were enacted, homicides increased by 20% in Puerto Rico.97 The erosion of trust in the police has had a lasting impact, particularly as patterns of police misconduct continued throughout the 2000s.

In 2011, the DOJ published a report entitled, “Investigation of the Puerto Rico Police Department.” The report documents concerning conduct by the police department, including several constitutional violations. In addition to use of excessive force, misconduct, and unlawful searches and seizures, the report found that the police department had failed to guide its officers on safe policing practices, had insufficient and/or nonexistent training, and lacked oversight on standards of policing.

Additionally, the report found that teams lacked supervision, internal investigations took too long, and the department’s tactical units had developed violent subcultures. The DOJ report also called out the department’s attempt at discipline as deficient and noted that it had an inoperable risk management system.98

As Giffords Law Center explored in a previous report, a strained relationship between the police and the people they serve can lead to higher rates of homicides and lower rates of contacting the police for help. For example, in 2011, while rates of violence decreased across Chicago, some neighborhoods experienced drastic spikes in violence. Researchers found that neighborhoods with low confidence and trust in the police experienced significantly higher homicide rates.99 Similarly in Milwaukee, after an instance of police brutality in 2005 involving a Black man, Milwaukee police saw 911 calls drop overall by 20%, with an even steeper drop within the city’s Black community.100

Efforts to Address Gun Violence in Puerto Rico

Giffords Law Center was unable to identify any specific programs supported by the government to prevent gun violence beyond traditional policing and criminal justice strategies. The only notable exception, the Puerto Rico Arms Law, establishes an educational campaign from November 15 to January 7 of every year to prevent unintentional shooting deaths.

Source

Andrew Anglemyer, Tara Horvath, and George Rutherford, “The Accessibility of Firearms and Risk for Suicide and Homicide Victimization among Household Members: A Systematic Review and Meta–Analysis,” Annals of Internal Medicine 160, no. 2 (2014): 101–110.

The campaign, “No Balas Al Aire,” seeks to stop residents from firing their guns into the air during the holiday season. The law was passed in response to the 2011 death of a young girl who died from a stray bullet shot in the air.101 Other than this campaign and corresponding law, neither the Puerto Rican government nor the federal government appears to engage in any other preventive campaign against the rampant gun violence in the commonwealth.

A number of residents and communities in Puerto Rico have taken it upon themselves to address the epidemic of gun violence in the territory. One feminist organization, Taller Salud, has been targeting gun violence in the city of Loíza since 2011. Loíza is a predominantly Black, low-income community that has historically experienced drastically high rates of gun violence. According to Executive Director Tania Rosario Mendez, “Taller Salud’s work challenges existing narratives about the identity of the Black and Afro-Puerto Rican man that criminalize poverty and blackness, and put our young Black men at risk.”102

Taller Salud’s program Acuerdo de Paz was modeled after Cure Violence, a community violence intervention program first launched in Chicago and now used in dozens of cities across the United States and internationally. Community violence intervention programs engage individuals at highest risk of being victims or perpetrators—or both—of violence. These programs can involve a variety of strategies to reach out to those involved in gun violence in their communities, build relationships and provide supportive social services, address conflict through nonviolent means like de-escalation and mediation, and work to support community healing from violence. Often, these strategies are rooted in a public health approach to violence prevention. In fact, Mendez said that Taller Salud and the Acuerdo de Paz program “redefined health to include and defend the right to a life free from violence.”

Taller Salud employs a variety of tactics to help stem soaring homicide rates, including a restorative justice strategy that employs conflict mediation, individual case management, risk reduction plans, community outreach, and educational campaigns. In an interview, Program Manager Zinnia Alejandro described these strategies, sharing, “For us, it is of the utmost importance to find solutions to problems…according to the culture, the idiosyncrasy, and the situation itself.”103

With this public health approach, Taller Salud has helped to substantially reduce gun violence in Loíza: in 2011, at the beginning of the program, there were 40 homicides in the small city,104 a rate 26 times the average rate of the 50 states.105 However, in 2018, there were only nine, a nearly 80% reduction.104

While Acuerdo de Paz has seen success, the program has been hampered by the lack of funding. As Giffords Law Center recently explored in a report highlighting the experiences of violence intervention workers in Chicago, Los Angeles, Oakland, and Baltimore, sustainable, long-term funding is desperately needed to ensure the continued effectiveness of community-based solutions to gun violence.

Additionally, March for Our Lives recently began a chapter out of the University of Puerto Rico in San Juan. The chapter aims to engage residents on the grassroots level as well as legislators.106 Both Taller Salud and March for Our Lives Puerto Rico demonstrate that Puerto Ricans recognize the gun violence epidemic and the need to prevent further deaths. The federal and Puerto Rican governments should follow their lead and do more to help save lives in the territory.

TAKE ACTION

The gun safety movement is on the march: Americans from different background are united in standing up for safer schools and communities. Join us to make your voice heard and power our next wave of victories.

GET INVOLVED

Recommendations

For too long, the epidemic of gun violence in the USVI and Puerto Rico has been ignored. The following recommendations represent actions that the federal and state governments can take to prevent gun violence and save lives. These recommendations were made after our conversations with key stakeholders, and local experts were asked for input in their creation when possible.

Create Systems to Monitor Gun Violence in All US Territories

In order to address gun violence in the US territories, adequate public health monitoring systems must be established to measure the scope and nature of the problem. As Giffords Law Center discovered in the course of conducting research, none of the US territories have easily accessible, up-to-date, and consistently released data on gun deaths.

As was mentioned earlier, the CDC funded the Puerto Rico Violent Death Reporting System as part of the National Violent Death Reporting System in 2016. The data from this project was cited heavily in this report, but data was only available through 2018—meaning that the three most recent years are unavailable. Because the PRVDRS project has been inadequately funded and understaffed, data on gun violence in Puerto Rico is less complete and less easy to access than the available data for the 50 states. Specifically, the lack of demographic data, such as age, gender, race/ethnicity, and/or socio-economic status, hinders the ability of researchers and advocates to fully grasp the extent of gun violence and who is most impacted.

There have been some recent efforts to bridge the gaps in data. In 2019, the PRVDRS received one year of funding to link firearm information, including gun trace data, to data on violent deaths. This project could provide crucial information about the legal and illegal firearms used in gun violence in Puerto Rico, and could help researchers better understand the nature of illegal gun markets and transactions.

Because the funding for this vital research lapsed after just one year, the kinds of trend analyses and conclusions that can be drawn from it are limited. The federal government should continue this funding to bridge the gaps in data and to better understand the extent of gun violence in the archipelago.

Increase Funding for Community Violence Intervention Programs

As in the 50 states, gun violence in Puerto Rico concentrates in large, urban areas such as the capital, San Juan, and other large cities like Ponce.107 Community violence intervention programs have already been proven effective in similar cities in the US. As a result of the success of these programs, President Biden called for a $5 billion investment in violence prevention strategies.108 The federal government should also commit funds to programs like Taller Salud in Loíza to help stem the high rates of gun violence in both the USVI and Puerto Rico.

Encourage States to Better Regulate Their Gun Markets

The trafficking of guns from the 50 states into the USVI and Puerto Rico substantially contributes to the high rates of gun violence in both places. As previously explored, the majority of the firearms recovered in crimes in both Puerto Rico and the USVI are trafficked in from US states, most frequently Florida, Georgia, and Texas. Research has shown that improving the regulation of gun markets leads to increased difficulty in purchasing guns on the illegal market.109

States with more laws regulating firearms are less likely to transfer firearms to other states.110 Another group of researchers demonstrated that states without universal background check laws export crime guns across state lines at a 30% higher rate than states that require background checks on all gun sales.111 Additionally, after the passage of the Maryland Firearm Safety Act, 41% of respondents to a survey of people engaged in the underground gun market reported increased difficulty in purchasing a firearm.112

Recently, the Biden-Harris administration recognized the need for more resources to combat gun trafficking by announcing new efforts to curtail the trafficking of firearms between states.113 While the actions announced by the administration will be important to stopping gun violence in the states, more must be done to stop the trafficking of guns into the USVI and Puerto Rico. The federal government and state governments—especially those in Florida, Georgia, and Texas—must work together to regulate local gun markets and stop gun trafficking from the states into these territories. The federal government should also explore screening procedures to increase detection of firearms that have been shipped illegally.

Finalize ATF Rule on Ghost Guns

In addition to the trafficked guns flowing into the USVI and Puerto Rico, multiple stakeholders have pointed to ghost guns as an increasingly alarming problem. ATF recently proposed a new rule regarding these untraceable firearms that would change the definition of a firearm to include components that are intentionally left unfinished. As a result, these parts could only be sold after a background check, and would have to be serialized. The new rule would help reduce the influx of personally manufactured firearms in both the USVI and Puerto Rico. The ATF rule must become policy as soon as possible so that these guns do not continue to fuel gun violence in the territories.

Conclusion

The American gun violence epidemic continues to rage on, even in places that are too often left out of the conversation. Advocates and courageous legislators must take action to save lives in Puerto Rico and the USVI, both of which suffer from staggeringly high rates of gun violence.

Gun violence is not an intractable problem, and the status quo is not acceptable. We know what the solutions are—now it’s time to enact them. With gun violence climbing in the 50 states and the territories, we must demand that our leaders act with courage and create equitable solutions to fix this problem.

Solving the gun violence epidemic in the USVI and Puerto Rico will require an investment from governments and people on all levels. We hope that this report spurs an increased engagement necessary to enact lasting, lifesaving solutions to gun violence.

Special Thanks

We would like to thank all of the stakeholders and experts who spoke with us and provided their insights in crafting this report, including: Tania Rosario Mendez, Zinnia Alejandro, and the staff at Taller Salud, especially the staff of the Acuerdo de Paz program, as well as Kemuel Delgado-Soto and the folks at March For Our Lives Puerto Rico, Dr. Diego Zavala and his team at the Puerto Rico Violent Death Reporting System, Javier Naranjo, Ángel Pérez Sánchez, Jean Vidal-Font, Mariana Nacer Elizalde, and Dr. Marisol LeBrón.

- Miguel Rivera Puig, “Sangriento fin de semana largo,” El Vocero, October 13, 2020, https://www.elvocero.com/ley-y-orden/sangriento-fin-de-semana-largo/article_87ff16b4-0ceb-11eb-b92e-c346ccf19ee8.html.[↩]

- Miguel Rivera Puig, “Fin de semana largo culmina con 15 asesinatos,” El Vocero, October 13, 2020, https://www.elvocero.com/ley-y-orden/fin-de-semana-largo-culmina-con-15-asesinatos/article_f27d6d3e-0d44-11eb-983b-e31f9b4af167.html.[↩]

- Bethaney Lee, “VIPD Condemns Weekend Shootings, Chastises Villa Owners for Parties,” St. Thomas Source, October 26, 2020, https://stthomassource.com/content/2020/10/26/vipd-condemns-weekend-shootings-chastises-villa-owners-for-parties/.[↩]

- The age-adjusted firearm mortality rate rose 17.8%, from 10.1 per 100,000 in 2010 to 11.9 per 100,000 in 2019. See Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Underlying Cause of Death, 1999-2019, 2020, CDC WONDER Online Database, http://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10.html. Data is from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 1999-2019, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.[↩]

- From 2015 to 2019, nearly 39,000 people died from gun violence. See Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Underlying Cause of Death, 1999-2019, 2020, CDC WONDER Online Database, http://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10.html. Data is from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 1999-2019, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.[↩]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Underlying Cause of Death, 1999-2020, 2022, CDC WONDER Online Database, http://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10.html. Data is from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 1999-2020, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.[↩]

- Reis Thebault et al., “2020 was the deadliest gun violence year in decades. So far, 2021 is worse,” The Washington Post, June 14, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2021/06/14/2021-gun-violence/.[↩]

- Erin Grinshteyn, et al., “Violent death rates in the US compared to those of the other high-income countries, 2015,” Preventive Medicine 123, (June 2019): 20-26, doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.02.026, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30817955/.[↩]

- The Global Burden of Disease 2016 Injury Collaborators (2018) estimated that in 2016, there were approximately 251,000 total firearm deaths globally, of which the US experienced roughly 37,200. See The Global Burden of Disease 2016 Injury Collaborators, “Global Mortality From Firearms, 1990-2016,” Journal of the American Medical Association 320, no. 8 (2018): 792-814, doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.10060, https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2698492.[↩]

- In 2018, the all-cause crude firearm mortality rate in Puerto Rico was 20.48 per 100,000. The all-cause firearm mortality rate in the 50 states in 2018 was 12.1 per 100,000. See Diego E Zavala-Zegarra, et al., Puerto Rico Institute of Statistics, Violent Deaths in Puerto Rico, 2018, 2020, https://estadisticas.pr/files/Publicaciones/Informe%20Muertes%20Violentas%202018_FINAL.11.30.21.pdf; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Underlying Cause of Death, 1999-2019, 2020, CDC WONDER Online Database, http://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10.html. Data is from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 1999-2019, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.[↩]

- The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration defines an archipelago as “an area that contains a chain or group of islands scattered in lakes, rivers, or the ocean.” See “What is an archipelago?” National Ocean Service, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/archipelago.html.[↩]

- Crude rate calculated from St. Thomas Source, which reported 44 out of 45 homicides in 2020 were committed with a gun. See “Homicides 2020,” St. Thomas Source, December 27, 2020, https://stthomassource.com/content/2020/12/27/253161/; US Census Bureau, “2020 Island Areas Censuses: U.S. Virgin Islands,” October 28, 2021, https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2020/dec/2020-us-virgin-islands.html.[↩]

- The crude firearm homicide rate for 2020 for the 50 states was 5.9 per 100,000. See Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Underlying Cause of Death, 1999-2020, 2022, CDC WONDER Online Database, http://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10.html. Data is from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 1999-2020, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.[↩]

- Guam, CMNI, and American Samoa have age-adjusted firearm mortality rates lower than the US rate of 10.6 per 100,000: 3.1 per 100,000, 2.8 per 100,000, and 1.9 per 100,000 respectively. See The Global Burden of Disease 2016 Injury Collaborators, “Global Mortality From Firearms, 1990-2016,” Journal of the American Medical Association 320, no. 8 (2018): 792-814, doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.10060, https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2698492.[↩]

- The firearms import rate for the USVI was 133.11 per 100,000 in 2020. Only Washington DC had a higher firearm import rate of 213.52 per 100,000. See Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, Number of Firearms Sourced and Recovered in the United States and Territories, 2020, https://www.atf.gov/resource-center/firearms-trace-data-2020.[↩][↩]

- Based on calculations made by Giffords Law Center. The lowest jurisdiction was Washington DC, with only four percent of firearms recovered by law enforcement originally sold in the District. See Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, Number of Firearms Sourced and Recovered in the United States and Territories, 2020, https://www.atf.gov/resource-center/firearms-trace-data-2020.[↩][↩]

- None of the territories have Electoral College votes and therefore residents of the territories cannot vote in presidential elections. Additionally, each territory has a representative in Congress but that representative cannot vote on bills on the floor of the House of Representatives.[↩]

- Residents of American Samoa are US nationals and not citizens. See Gabriela Meléndez Olivera, et al., “‘Nationals’ but not ‘Citizens’: How the U.S. Denies Citizenship to American Samoans,” ACLU, August 6, 2021, https://www.aclu.org/news/voting-rights/nationals-but-not-citizens-how-the-u-s-denies-citizenship-to-american-samoans.[↩]

- For example, the Global Burden of Disease 2016 Injury Collaborators (2018) had the most inclusive definition of gun violence, referencing all ICD-10 codes in which a firearm was involved including the following categories: interpersonal violence by firearm, self-harm by firearm, unintentional injury by firearm, executions and police conflict, and conflict and terrorism. Other attempts to describe gun violence had varying inclusion criteria. The Puerto Rico Violent Death System utilizes the National Violent Death System, which does not categorize homicides where law enforcement shoots an individual as an act of terriorism. Zavala-Zegarra et al. (2012) did not include accidental homicides or legal-intervention homicides if there were less than five a year. See The Global Burden of Disease 2016 Injury Collaborators, “Global Mortality From Firearms, 1990-2016,” Journal of the American Medical Association 320, no. 8 (2018): 792-814, doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.10060, https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2698492; Diego E Zavala-Zegarra, et al., “Geographic distribution of risk of death due to homicide in Puerto Rico, 2001-2010,” Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública 32, no. 5 (2012): 321-329, https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/9250.[↩]

- All interviews were conducted virtually.[↩]

- Chris Woolf, “How a violent history created the US Virgin Islands as we know them,” The World, September 13, 2017, https://www.pri.org/stories/2017-09-13/how-violent-history-created-us-virgin-islands-we-know-them.[↩]

- “U.S. Virgin Islands,” Office of Insular Affairs, US Department of the Interior, last accessed November 18, 2021, https://www.doi.gov/oia/islands/virgin-islands.[↩]

- “Understanding the Population of the U.S. Virgin Islands,” US Census Bureau, 2020, https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/programs-surveys/sis/resources/2020/sis_2020map_usvi_k-12.pdf.[↩]

- Steve Wilson, et al., “2020 Population of U.S. Island Areas Just Under 339,000,” October 28, 2021, https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/10/first-2020-census-united-states-island-areas-data-released-today.html.[↩]

- See 23 V.I.C. §§ 452, 455, 466.[↩]

- 14 V.I.C. § 2256(a).[↩]

- 23 V.I.C. § 455.[↩]

- 23 V.I.C. § 456a(a).[↩]

- USVI law defines specific offenses, including attempts, as disqualifying crimes of violence: “murder in any degree, voluntary manslaughter, rape, arson, discharging or aiming firearms, mayhem, kidnapping, assault in the first degree, assault in the second degree, assault in the third degree, robbery, burglary, unlawful entry or larceny.” 23 V.I.C. 451(g).[↩]

- A license cannot be issued to “a person who is manifestly psychotic or otherwise of unsound mind, either consistently or sporadically, by reason of mental defect, among which are retardation, schizophrenia or other acute hallucinatory and delusory defects of mind, certain types of epilepsy or other seizure disorders which render the individual coordinated and mobile but of unsound mind, bipolar disorder which results in sporadic psychosis, and other disorders which consistently or sporadically render the person starkly incapable of maintaining awareness of and responsibility for his actions.” 23 V.I.C. § 458(b)(1).[↩]

- 23 V.I.C. § 458(a).[↩]

- Id.[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- 23 V.I.C. § 453(a).[↩]

- 23 V.I.C. § 454a(a).[↩]

- See Cassandra K. Crifasi, et al., “Association Between Firearm Laws and Homicide in Urban Counties,” Journal of Urban Health 95, no. 3 (2018): 383–390; Alexander D. McCourt et al., “Purchaser licensing, point-of-sale background check laws, and firearm homicide and suicide in 4 US states, 1985-2017,” American Journal of Public Health 110, no. 10 (2020), https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/abs/10.2105/AJPH.2020.305822; Michael Siegel et al., “Easiness of Legal Access to Concealed Firearm Permits and Homicide Rates in the United States,” American Journal of Public Health 107, (2017), https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/abs/10.2105/AJPH.2017.304057.[↩]

- See Sae Takada, et al., “Firearm laws and the network of firearm movement among US states,” BMC Public Health 21, no. 1803 (2021), https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11772-y; Tessa Collins et al., “State Firearm Laws and Interstate Transfer of Guns in the USA, 2006-2016,” J Urban Health 95, (2018), https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-018-0251-9.[↩]

- The estimated number of firearm deaths rose from 19 to 22.6 from 1990 to 2016 respectively in the USVI. See The Global Burden of Disease 2016 Injury Collaborators, “Global Mortality From Firearms, 1990-2016,” Journal of the American Medical Association 320, no. 8 (2018): 792-814, doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.10060, https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2698492.[↩]

- This comparison was calculated from a number of sources. 2016 was the latest year the FBI published the number of gun homicides for the USVI. According to the 2016 Crime in the US Report, 34 people died from gun homicides in the USVI. 40 total homicides were committed. Since a population estimate for 2016 is unavailable, using the USVI population numbers from the 2010 Census, we calculate a crude gun homicide rate of 32 per 100,000. The national crude gun homicide rate in 2016 was 4.5 per 100,000. See “Table 12: Murder by State, Types of Weapons, 2016,” Crime in the United States, Uniform Crime Reporting, FBI, last accessed November 18, 2021, https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2016/crime-in-the-u.s.-2016/tables/table-12; “Understanding the Population of the U.S. Virgin Islands,” US Census Bureau, 2020, https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/programs-surveys/sis/resources/2020/sis_2020map_usvi_k-12.pdf; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Underlying Cause of Death, 1999-2019, 2020, CDC WONDER Online Database, http://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10.html. Data is from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 1999-2019, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.[↩]

- Based on Giffords Law Center estimates compared to CDC data. See Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Underlying Cause of Death, 1999-2019, 2020, CDC WONDER Online Database, http://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10.html. Data is from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 1999-2019, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.[↩]

- This comparison was calculated from a number of sources. City-specific data is from The Trace and the USVI rate is based on calculations made by Giffords Law Center using the 2010 decennial population estimate. In 2016, 34 out of 42 homicides in the USVI were gun homicides. See Francesca Mirabelle and Daniel Nass, “What’s the Homicide Capital of America? Murder Rates in U.S. Cities, Ranked,” The Trace, April, 26, 2018, https://www.thetrace.org/2018/04/highest-murder-rates-us-cities-list/; “Table 12: Murder by State, Types of Weapons, 2016,” Crime in the United States, Uniform Crime Reporting, FBI, last accessed November 18, 2021, https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2016/crime-in-the-u.s.-2016/tables/table-12; “Understanding the Population of the U.S. Virgin Islands,” US Census Bureau, 2020, https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/programs-surveys/sis/resources/2020/sis_2020map_usvi_k-12.pdf.[↩]

- “Table 20: Murder by State, Types of Weapons, 2010,” Crime in the United States, Uniform Crime Reporting, FBI, last accessed November 18, 2021, https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2010/crime-in-the-u.s.-2010/tables/10tbl20.xls.[↩]

- Calculated from the St. Thomas Source, which reported that 44 out of 45 homicides in 2020 were committed with a gun. See “Homicides 2020,” St. Thomas Source, December 27, 2020, https://stthomassource.com/content/2020/12/27/253161/.[↩]

- As of January 2022, 42 of the 45 homicides reported by the St. Thomas Source were gun homicides. See “Homicides 2021,” St. Thomas Source, last accessed January 3, 2022, https://stthomassource.com/content/2021/01/13/281044/.[↩]

- Based on calculations made by Giffords Law Center. See “Homicides 2021,” St. Thomas Source, October 29, 2021, https://stthomassource.com/content/2021/01/13/281044/; US Census Bureau, “2020 Island Areas Censuses: U.S. Virgin Islands,” October 28, 2021, https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2020/dec/2020-us-virgin-islands.html.[↩]

- US Attorney’s Office, District of the Virgin Islands, “St. Croix Couple Arrested for Firearms Trafficking Involving over 100 Illegally Manufactured Firearms Sold Throughout the U.S. Virgin Islands,” news release, March 22, 2021, https://www.justice.gov/usao-vi/pr/st-croix-couple-arrested-firearms-trafficking-involving-over-100-illegally-manufactured.[↩]

- Id.[↩][↩]

- “NICS Firearm Background Checks: Month/Year by State,” FBI, last accessed December 21, 2021, https://www.fbi.gov/file-repository/nics_firearm_checks_-_month_year_by_state.pdf/view; Steven Wilson, et al., “2020 Population of U.S. Island Areas Just Under 339,000,” US Census Bureau, October 28, 2021, https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/10/first-2020-census-united-states-island-areas-data-released-today.html.[↩]

- According to data published by The Trace and calculations made by Giffords Law Center, the USVI saw an unadjusted gun purchasing rate of approximately 485 purchases per 100,000 in 2020. That ranked the lowest among states and territories with data available. Hawaii, Guam, American Samoa, and the CNMI did not have data available. See Daniel Nass and Champe Barton, “How Many Guns Did Americans Buy Last Month? We’re Tracking the Sales Boom,” The Trace, December 1, 2021, https://www.thetrace.org/2020/08/gun-sales-estimates/.[↩]

- Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, Number of Firearms Sourced and Recovered in the United States and Territories, 2020, https://www.atf.gov/resource-center/firearms-trace-data-2020.[↩]

- Suzanne Carlson, “Illegal guns fueling violence,” Virgin Island Daily News, March 25, 2019, http://www.virginislandsdailynews.com/news/illegal-guns-fueling-violence/article_07f67aa7-2092-5e4b-8ad1-5141a62a3586.html.[↩]

- Congresswoman Stacey Plaskett, “Congresswoman Plaskett Releases Statement on Recent Wave of Gun Violence on St. Croix”, February 28, 2021, https://plaskett.house.gov/news/documentsingle.aspx?DocumentID=3755.[↩]

- These two individuals spoke to us of their own volition and did not speak in any capacity representing their former agencies nor the federal government.[↩]

- Based on calculations made by Giffords Law Center. See “U.S. Virgin Islands: Data Source: Firearms Tracing System, January 1, 2019 – December 31, 2019,” Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, last accessed December 21, 2021, https://www.atf.gov/file/147351/download; “U.S. Virgin Islands: Data Source: Firearms Tracing System, January 1, 2018 – December 31, 2018,” Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, last accessed December 21, 2021, https://www.atf.gov/file/137276/download; “U.S. Virgin Islands: Data Source: Firearms Tracing System, January 1, 2017 – December 31, 2017,” Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, last accessed December 21, 2021, https://www.atf.gov/resource-center/docs/undefined/viwebsite17183918pdf/download; “U.S. Virgin Islands, January 1, 2016 – December 31, 2016,” Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, last accessed December 21, 2021, https://www.atf.gov/file/119446/download; “U.S. Virgin Islands, January 1, 2015 – December 31, 2015,” Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, last accessed December 21, 2021, https://www.atf.gov/docs/163554-viatfwebsite15pdf/download.[↩]

- Id.[↩]

- It should be noted that Florida consistently received an F from the Giffords Law Center Annual Gun Law Scorecard until gun safety legislation was passed following the Parkland shooting in 2018. See “Annual Gun Law Scorecard,” Giffords Law Center, last accessed on November 18, 2021, https://giffords.org/lawcenter/resources/scorecard/.[↩]

- “Firearms Trace Data: U.S. Virgin Islands – 2020,” Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, last accessed December 21, 2021, https://www.atf.gov/resource-center/firearms-trace-data-us-virgin-islands-2020.[↩]

- US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Following the Gun: Enforcing Federal Laws Against Firearms Traffickers, June 2000, https://www.ojp.gov/ncjrs/virtual-library/abstracts/following-gun-enforcing-federal-laws-against-firearms-traffickers.[↩]

- US Attorney’s Office, District of the Virgin Islands, “United States Attorney Shappert Announces USVI Efforts to Address Violent Crime: Project Guardian and Project Safe Neighborhoods,” news release, October 13, 2020, https://www.justice.gov/usao-vi/pr/united-states-attorney-shappert-announces-usvi-efforts-address-violent-crime-project.[↩]

- “About Project Guardian,” Office of the Attorney General, US Department of Justice Archives, May 26, 2021, https://www.justice.gov/archives/ag/about-project-guardian.[↩]

- “Project SAFE Neighborhoods,” United States Virgin Islands Police Department, last accessed November 18, 2021, http://www.vipd.gov.vi/Civilian/Project_SAFE_Neighborhoods.aspx.[↩]

- “Puerto Rico – History and Heritage,” Smithsonian Magazine, November 6, 2007, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/travel/puerto-rico-history-and-heritage-13990189/.[↩]

- Jacqueline N. Font-Guzmán, “Puerto Ricans are hardly US citizens. They are colonial subjects,” Washington Post, December 13, 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/puerto-ricans-are-hardly-us-citizens-they-are-colonial-subjects/2017/12/13/c0f1c700-de9f-11e7-89e8-edec16379010_story.html.[↩]

- Guam remains a US territory. See “Puerto Rico – History and Heritage,” Smithsonian Magazine, November 6, 2007, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/travel/puerto-rico-history-and-heritage-13990189/.[↩]

- Verónica Rivera-Negrón, “Through a Puerto Rican lens: The legacy of the Jones Act,” National Museum of American History, February 28, 2017, https://americanhistory.si.edu/blog/through-puerto-rican-lens-legacy-jones-act.[↩]

- Smithsonian.com, “Puerto Rico – History and Heritage,” Smithsonian Magazine, November 6, 2007, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/travel/puerto-rico-history-and-heritage-13990189/.[↩]

- “Historical Population Change Data (1910-2020),” US Census Bureau, April 26, 2021, https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/dec/popchange-data-text.html.[↩]

- Vice News, “Guns in Puerto Rico: Locked and Loaded in the Tropics,” January 6, 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=47gxjk6u5cq.[↩]

- See 25 L.P.R.A. §§ 462a(e), 466b, 466d. Members of the US military and members of the Puerto Rico National Guard are exempt from these requirements, as are law enforcement officers provided that they receive training in weapons operation and handling. 25 L.P.R.A. § 462d.[↩]

- 25 L.P.R.A. § 462a.[↩]

- 25 L.P.R.A. § 462h.[↩]

- 25 L.P.R.A. § 462f.[↩]

- See 25 L.P.R.A. § 462a(e).[↩]

- 25 L.P.R.A. § 462a(e)(1).[↩]

- 25 L.P.R.A. §§ 462a(e)(4), 462a(e)(5).[↩]

- According to FBI data, in Puerto Rico there were 31,671 and 74,381 background checks for firearm purchases in 2020 and 2021, respectively. See “NICS Firearm Checks: Month/Year by State,” FBI, last accessed December 21, 2021, https://www.fbi.gov/file-repository/nics_firearm_checks_-_month_year_by_state.pdf/view.[↩]

- “Homicide Monitor,” Igarápe Institute, last accessed November 18, 2021, https://homicide.igarape.org.br/.[↩][↩]

- Fernando I. Rivera, “Puerto Rico’s population before and after Hurricane Maria,” Population and Environment, (July 29, 2020): 1-3, doi: 10.1007/s11111-020-00356-4, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7387120/.[↩]

- In the past year, the PRVDRS received pilot funding to link homicides with information on the firearm used in the crime, including whether the firearm was bought legally; any alterations made to the firearm, such as converting it to fire automatically; whether the firearm is linked to other homicides; and gun tracing data.[↩]

- Note: mortality data for the US Virgin Islands was not available for 2017.[↩]

- In Puerto Rico, the crude firearm suicide rate for 2018 was 1.4 per 100,000. Nationally, the crude firearm suicide rate was 7.5 per 100,000. See Diego E Zavala-Zegarra, et al., Puerto Rico Institute of Statistics, Violent Deaths in Puerto Rico, 2018, 2020, https://estadisticas.pr/files/Publicaciones/Informe%20Muertes%20Violentas%202018_FINAL.11.30.21.pdf; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Underlying Cause of Death, 1999-2019, 2020, CDC WONDER Online Database, http://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10.html. Data is from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 1999-2019, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.[↩]

- Nicole Acevedo, “Suicide rates spike in Puerto Rico, five months after Maria,” NBC News, February 20, 2018, https://www.nbcnews.com/storyline/puerto-rico-crisis/suicide-rates-spike-puerto-rico-five-months-after-maria-n849666; David Cordero Mercado, “Continúa en alza la cifra de suicidios en Puerto Rico,” Metro, March 1, 2019, https://www.metro.pr/pr/noticias/2019/03/01/continua-alza-la-cifra-suicidios-puerto-rico.html.[↩]

- There were 35 firearm suicides in 2017 and 44 firearm suicides in 2018 resulting in a 26% increase. See Diego E Zavala-Zegarra, et al., Puerto Rico Institute of Statistics, Violent Deaths in Puerto Rico, 2018, 2020, https://estadisticas.pr/files/Publicaciones/Informe%20Muertes%20Violentas%202018_FINAL.11.30.21.pdf.[↩]

- The national gun homicide rate in 2018 was 4.3 per 100,000. See Diego E Zavala-Zegarra, et al., Puerto Rico Institute of Statistics, Violent Deaths in Puerto Rico, 2018, 2020, https://estadisticas.pr/files/Publicaciones/Informe%20Muertes%20Violentas%202018_FINAL.11.30.21.pdf; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Underlying Cause of Death, 1999-2019, 2020, CDC WONDER Online Database, http://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10.html. Data is from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 1999-2019, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.[↩]

- Diego E Zavala-Zegarra, et al., “Geographic distribution of risk of death due to homicide in Puerto Rico, 2001-2010,” Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública 32, no. 5 (2012): 321-9, https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/9250.[↩]

- In 2016, San Juan had a homicide rate of 43.4 per 100,000. Only four other major US cities had higher homicide rates: St. Louis, MO (61.6 per 100,000), Baltimore, MD (51.7 per 100,000), Detroit, MI (44.2 per 100,000), and New Orleans, LA (44.2 per 100,000). The next closest city was Cleveland, OH (35.0 per 100,000). See “Homicide Monitor,” Igarápe Institute, last accessed November 18, 2021, https://homicide.igarape.org.br/; Francesca Mirabelle, et al., “What’s the Homicide Capital of America? Murder Rates in U.S. Cities, Ranked,” The Trace, September 28, 2021, https://www.thetrace.org/2018/04/highest-murder-rates-us-cities-list/.[↩]

- In 2018, there were 671 homicides in Puerto Rico. A woman was the victim in 52 of these homicides, accounting for approximately 7.7% of all violent homicides. See Diego E Zavala-Zegarra, et al., Puerto Rico Institute of Statistics, Violent Deaths in Puerto Rico, 2018, 2020, https://estadisticas.pr/files/Publicaciones/Informe%20Muertes%20Violentas%202018_FINAL.11.30.21.pdf.[↩]

- There were 1,125 incidents of domestic violence with male victims in 2019. See “Estadísticas de Violencia Doméstica,” Puerto Rico Police Department, 2020, https://policia.pr.gov/estadisticas-de-violencia-domestica/.[↩]

- Madison Hall, et al., “2020 was the deadliest year on record for transgender people in the US, Insider database shows. Experts say it’s getting worse,” Insider, April 20, 2021, https://www.insider.com/insider-database-2020-deadliest-year-on-record-for-trans-people-2021-4-.[↩]

- Alexandra Kelly, “Puerto Rico declares state of emergency over explosion of femicides, violence against women,” The Hill, January 25, 2021, https://thehill.com/changing-america/respect/equality/535717-puerto-rico-declares-state-of-emergency-over-explosion-of; Harmeet Kaur, et al., “Puerto Rico declares a state of emergency due to gender-based violence,” CNN, January 25, 2021, https://www.cnn.com/2021/01/25/us/puerto-rico-emergency-gender-violence-trnd/index.html; Adrian Florido, “Puerto Rico’s Governor Declares State Of Emergency Over Gender Violence,” NPR, January 26, 2021, https://www.npr.org/2021/01/26/960855914/puerto-ricos-governor-declares-state-of-emergency-over-gender-violence.[↩]

- US Attorney’s Office, District of the Virgin Islands, “Federal Charges For Weapons Trafficking And Carjacking,” news release, February 9, 2018, https://www.justice.gov/usao-pr/pr/federal-charges-weapons-trafficking-and-carjacking.[↩]

- According to data from ATF and based on calculations made by Giffords staff, there are 2.1 Federal Firearms Licensees (FFLs), or establishments that can legally sell firearms, for every 100,000 residents in Puerto Rico. That is the lowest number compared to the 50 states and the other territories, with the closest rate being 3.84 per 100,000 in New Jersey. However, Washington DC has an even smaller rate of FFLs, with 0.87 per 100,000. See “Federal Firearms Listings,” Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, 2021, https://www.atf.gov/firearms/listing-federal-firearms-licensees; “Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for the United States, Regions, States, and the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico, April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2019; April 1, 2020; and July 1, 2020 (NST-EST2020),” US Census Bureau, last accessed December 17, 2021, https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/popest/technical-documentation/research/evaluation-estimates/2020-evaluation-estimates/2010s-state-total.html.[↩]

- “NICS Firearm Background Checks: Month/Year by State,” FBI, last accessed December 21, 2021, https://www.fbi.gov/file-repository/nics_firearm_checks_-_month_year_by_state.pdf/view; “Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for the United States, Regions, States, and the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico, April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2019; April 1, 2020; and July 1, 2020 (NST-EST2020),” US Census Bureau, last accessed December 17, 2021, https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/popest/technical-documentation/research/evaluation-estimates/2020-evaluation-estimates/2010s-state-total.html.[↩]

- US Attorney’s Office, District of the Virgin Islands, “Former Puerto Rico Police Officer And Associate Indicted And Arrested For Dealing In Firearms Without A License,” news release, November 4, 2019, https://www.justice.gov/usao-pr/pr/former-puerto-rico-police-officer-and-associate-indicted-and-arrested-dealing-firearms.[↩]

- Marisol LeBrón, “They Don’t Care if We Die: The Violence of Urban Policing in Puerto Rico,” Journal of Urban History 46, no. 5 (published online May 1, 2017, issue published September 1, 2020): 2, doi: 10.1177/0096144217705485, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0096144217705485/.[↩]

- Id at 6.[↩]

- Id at 3.[↩]

- Id at 11.[↩]

- US Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division, Investigation of the Puerto Rico Police Department, September 5, 2011, https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/crt/legacy/2011/09/08/prpd_letter.pdf.[↩]

- David S. Kirk, et al., “Cultural Mechanisms and the Persistence of Neighborhood Violence,” American Journal of Sociology 116, no. 4 (January 2011), doi: 10.1086/655754, https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/655754.[↩]

- Matthew Desmond, et al., “Police Violence and Citizen Crime Reporting in the Black Community,” American Sociological Review 81, no. 5 (2016): 857-876, doi: 10.1177/0003122416663494, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0003122416663494.[↩]

- “Policía inicia campaña para prevenir disparos al aire en Navidad y Año Nuevo,” WIPR, November 17, 2020, https://wipr.pr/policia-inicia-campana-para-prevenir-disparos-al-aire-en-navidad-y-ano-nuevo/.[↩]

- Interview with Tania Rosario Mendez (Taller Salud), August 16, 2021.[↩]

- Interview with Zinnia Alejandro (Taller Salud), August 16, 2021.[↩]

- Materials and data provided by Taller Salud and on file with Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence.[↩][↩]

- The homicide rate in Loíza in 2011 was 133 per 100,000. The US national crude homicide rate was 5.2 per 100,000. See Materials and data provided by Taller Salud and on file with Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Underlying Cause of Death, 1999-2019, 2020, CDC WONDER Online Database, http://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10.html. Data is from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 1999-2019, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.[↩]

- Interview with Kemuel Delgado-Soto (March For Our Lives Puerto Rico), March 8, 2021.[↩]

- Diego E. Zavala-Zegarra, et al., “Geographic distribution of risk of death due to homicide in Puerto Rico, 2001-2010,” Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública 32, no. 5 (2012): 321-9, https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/9250.[↩]

- Juana Summers, “$5 Billion For Violence Prevention Is Tucked Into Biden Infrastructure Plan,” NPR, April 1, 2021, https://www.npr.org/2021/04/01/983103198/-5-billion-for-violence-prevention-is-tucked-into-biden-infrastructure-plan.[↩]

- See Sae Takada, et al., “Firearm laws and the network of firearm movement among US states,” BMC Public Health 21, no. 1803 (2021), https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11772-y; David M. Hureau, et al., “The Trade in Tools: The Market for Illicit Guns in High–Risk Networks,” Criminology 56, no. 3 (August 2018): 510-45, https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9125.12187.[↩]

- Erin G. Andrade, et al., “Firearm laws and illegal firearm flow between US states,” Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 88, no. 6 (June 2020): 752-9, doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000002642, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32102044/.[↩]

- Daniel W. Webster, et al., “Effects of State-Level Firearm Seller Accountability Policies on Firearm Trafficking,” Journal of Urban Health 86, no. 4 (July 2009): 525–37, doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9351-x, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2704273/; Daniel W. Webster, et al., “Preventing the diversion of guns to criminals through effective firearm sales laws,” Reducing Gun Violence in America: Informing Policy with Evidence and Analysis, (January 2013): 109-21, https://jhu.pure.elsevier.com/en/publications/preventing-the-diversion-of-guns-to-criminals-through-effective-f-3.[↩]