Latino Voices in Florida: Thinking, Talking & Voting about Gun Violence

Our research with this growing group of Sunshine State constituents shows gun violence is a top election issue.

The Latino community is an integral part of the evolving demographic landscape across the Sunshine State. And while data shows that gun violence takes a grueling toll on Latinos in Florida, there has been little research on how this growing and changing population feels, talks about—and votes—when it comes to the pervasive issue of gun violence.

Over several months in 2024, GIFFORDS embarked on a qualitative research project to better understand Latinos’ perspectives on gun violence, their attitudes on guns and gun policy, and how their cultural background influences their views on these topics. We sought to speak with a diverse sample of Latinos, including people from a range of diaspora communities and of different generational statuses.

At its core, this project centers the voices and perspectives of Latinos in Florida and attempts to present the diverse and complicated views members of this community shared with us. Our hope is that this project helps organizations, political candidates, and others who work with the Latino community across Florida to better understand the diversity of this population, its concerns about gun violence, and its desire for action to address this crisis.

The terms “Hispanic” and “Latino” are often used interchangeably to describe this group, though these terms technically have different meanings. Latino refers to people of Latin American origin, while Hispanic refers to people of Spanish-speaking origin.1 This report generally uses the term Latino, except when referring to specific demographic data or sources that use the term Hispanic.

MEDIA REQUESTS

Our experts can speak to the full spectrum of gun violence prevention issues. Have a question? Email us at media@giffords.org.

Contact

The number of Latino residents and, even more critically, Latino voters, is growing rapidly in Florida. In fact, Florida has the third-largest Latino population among US states.2 Roughly one in ten Latinos in the US live in Florida, and more than one in four people living in Florida are Latino.3 This is the fastest growing ethnic group in Florida: between 2010 and 2022, Florida’s total population grew from 18.8 million to 22.2 million, an increase of 18%. During the same period, the state’s Hispanic and Latino population grew from 4.2 million to 6 million, an increase of 43%.3

The rise in the overall Latino population in Florida has also led to a rise in Latino voters. Latinos now account for nearly one in four (22%) registered voters in the state,4 and more than two million Latinos in Florida are projected to vote in the 2024 election—up 14% from the 2020 presidential election.5

In addition to their growing share of the population, Latinos in Florida are uniquely diverse in terms of their cultural backgrounds and political leanings compared to the national Latino population. For example, in 2022, Latino residents of Cuban descent represented the single largest Hispanic ethnic group in Florida (26%), while Puerto Ricans (21%), Mexicans (12%), Colombians (7%), and Venezuelans (6%) comprised the next four largest ethnic groups.6 In comparison, Mexican Americans (59%) were the largest Hispanic ethnic group nationally, followed by Puerto Ricans (9%), Salvadorans (4%), Cubans (4%), and Dominicans (4%).3

The diversity in ethnic backgrounds of Florida’s Latino population likely influences the political diversity among this group in the state. Nationally, Latino voters are more than three times as likely to identify as Democrats than Republicans (54% vs. 16%).7 However, in Florida, these margins are much closer, with recent polling showing that 31% of Latino voters identify as Democrats, 31% as Republicans, and 38% as Independents.8 These proportions are different from Florida registered voters as a whole, where 32% are registered as Democrats, 39% as Republicans, and 26% have no party affiliation.9

Finally, gun violence has an enormous impact on the safety and voting decisions of Latinos in Florida. In an average year, more than 400 Latinos are killed by guns in Florida.10 Roughly equal proportions of these deaths are gun suicides (50%) and gun homicides (46%).3 Gun deaths are also the second leading cause of death for Latino children and teens in Florida—outpacing deaths from drowning and cancer.3

Alarmingly, gun deaths among the Latino community in Florida are rising, even controlling for population increase in the state among this group. In fact, from 2010 to 2022, the overall gun death rate for Latino residents rose 33%; the gun homicide rate rose 40% over this same period among this group.3 These increases are sharper than those observed in the state overall (13% increase in overall gun death rate; 5% increase in gun homicide rate) and among non-Hispanic white residents (12% increase in overall gun death rate; 0.4% decrease in gun homicide rate).3

Given the increasing toll that gun violence takes on this group, it is unsurprising that gun safety has become a key voting issue for the Latino community in Florida, with Latino voters more likely to list gun violence among their top issues.8 In fact, gun safety is one of the top 10 determining issues for Latino voters in Florida when it comes to selecting candidates.3

Collectively, these factors provide an excellent opportunity to further understand how Latino Floridians view gun violence and gun policy and how to best engage this community around this issue.

For this project, GIFFORDS conducted 20 semi-structured one-on-one interviews with Latinos across the state of Florida. Interview subjects were recruited through purposive sampling intended to help ensure that our final sample was diverse along lines of gender, age, occupation, geography, political party affiliation, and diaspora of origin. Additionally, to capture differences between US-born and foreign-born Latinos, we intentionally worked to recruit equal numbers of these participants. Given that some of our questions asked about voting behaviors, we only recruited participants who were US citizens and eligible to vote. To create our diverse sample, GIFFORDS partnered with We Are Más, a Florida-based consulting firm that applies a culturally competent approach to engage Latinos of different diasporas on a variety of issues, to recruit participants as well as to assist in conducting bilingual interviews.

For each interview, we used a standard interview guide that included questions about people’s experiences with gun violence, their attitudes toward guns, and how their cultural background influences their views on these topics. Interviews were conducted between April 19, 2024, and June 1, 2024, and generally lasted between 40 and 60 minutes. Each interview was conducted over Zoom, and all sessions were recorded, transcribed, and qualitatively coded to identify common and divergent themes from the interviews. Upon completion of the interview, all participants received a $50 gift card.

Participants had the option to complete interviews in English or Spanish, and all interviews included at least one bilingual interviewer. All interviews conducted in Spanish were translated to English for analysis. Our final sample included 11 Spanish-language interviews and nine English-language interviews.

Participants in our sample were nearly evenly split between men (n=8) and women (n=12). The average participant was 45 years old, but participants ranged in age from 21 to 64. The majority (n=16) of participants in our sample were parents.

Participants lived in a variety of geographic regions in Florida, with more populous counties comprising a larger percentage of the sample. Seven participants lived in Broward County, five in Miami-Dade, three in Hillsborough, two in Orange, one in Duval, one in Osceola, and one in Pinellas. Within these counties, both urban and suburban areas were represented.

Our sample included 11 foreign-born participants and nine US-born participants. Among the foreign-born participants, there was significant diversity in the time since immigration to the US. The average foreign-born participant had lived in the US for 26 years, but this value ranged from three years to 57 years in our sample.

In terms of diaspora representation, four participants identified as Cuban, three as Puerto Rican, three as Colombian, and three as Venezuelan. Two participants identified as belonging to two diaspora groups (Salvadoran and Uruguayan; Guatemalan and Mexican). The remaining participants identified as Mexican, Nicaraguan, Ecuadorian, Dominican, and Argentinian.

Our sample also featured substantial diversity in terms of occupation. Participants held a wide range of jobs, from business owners, teachers, and a doctor to community organizers, a student, and a swim instructor.

In terms of political affiliations, nine participants described themselves as Democrats, seven as Independents, two as Republicans, and one person said they did not identify with any of these affiliations.11 Importantly, party identification was based only on how participants described themselves, not what was reflected in their actual voter registration.

Our sample also included some representation from gun owners and people who lived in homes with guns. Three of our participants personally owned guns, and another three participants did not personally own a gun but lived with someone who did. One participant self-identified during the interview as a former NRA member, although a question about NRA membership was not systematically asked of all participants.

Our sample also included at least two members of LGBTQ+ community, who self-identified as such during the course of our interviews, as well as one member of the deaf community.

GET THE FACTS

Gun violence is a complex problem, and while there’s no one-size-fits-all solution, we must act. Our reports bring you the latest cutting-edge research and analysis about strategies to end our country’s gun violence crisis at every level.

Learn More

Gun Violence Is a Substantial Concern to Latinos in Florida

Universally among participants, gun violence was a significant concern and something that people worried about with some regularity. One participant described how she felt “enveloped” by gun violence; another described gun violence as “practically a disease that is destroying and eating up the foundations of American society.”

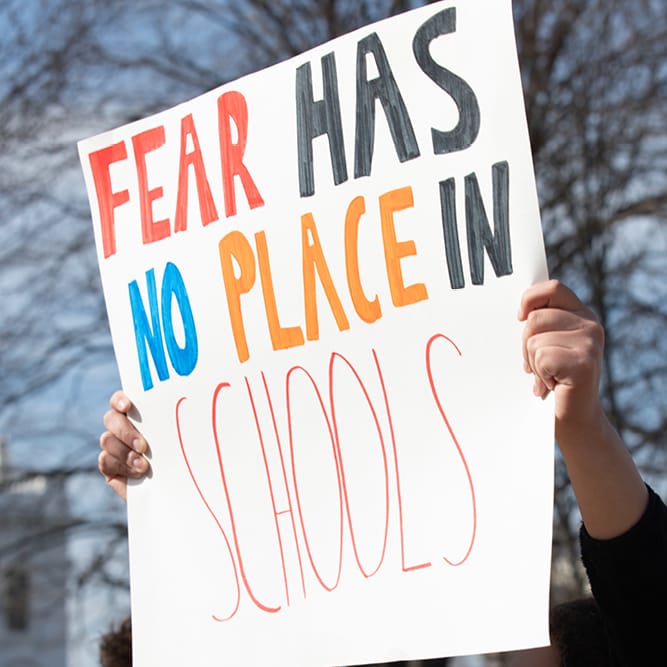

For many participants, concerns about gun violence were directly related to concerns about their children’s safety, particularly in schools. In fact, 18 of the 20 participants referenced violence in schools as one of their most salient worries regarding gun violence. One participant, a teacher from Miami, described how she fears both for her child’s safety as well as the safety of her students:

Other parents similarly described how becoming a parent augmented and amplified their concerns about gun violence. Younger participants often expressed concerns about their younger siblings or people attending the schools that they recently graduated from.

Additionally, several participants expressed concern and frustration over the sense that gun violence could erupt at any moment, given the easy and abundant access to guns in Florida and across the country.

- “Here in Florida, it seems like it’s a common thing to pull a gun during a conflict.” —53-year-old man, born in Venezuela

- “Anyone… out of spite, out of anger in the car, any type of rage can immediately access their gun and do God knows what.” —34-year-old woman, born in Nicaragua

- “It’s scary how much power [guns have], because a lot of people can, over any simple thing, can just pull out a gun and shoot out at anybody.” —21-year-old woman, born in the US and of Cuban ancestry

- “I think that Florida is reaching a level as ugly as Texas, or the states where people walk around with rifles and weapons everywhere—that’s where we are headed.” —58-year-old transgender woman, born in Colombia

Importantly, very few participants framed gun violence around issues like domestic violence or gun suicide. Only two participants specifically talked about firearms being used in domestic violence, and only one participant talked directly about gun suicide. Several participants did mention unintentional shootings, predominantly among children, being a concern.

For many participants, concerns about gun violence were largely related to what they observed in their community or on the news. Most participants did not directly identify themselves as survivors, yet more than half of the participants (n=12) described either a personal experience with gun violence or knowing someone who had experienced gun violence in their broader social networks.

Among this group, proximity to gun violence exposure, the type of gun violence exposure, and where the exposure was experienced varied widely. For example, among those who identified as direct survivors, the sample included a man who was shot in Venezuela before moving to the US, a mother who lost her son in the 2016 Pulse nightclub shooting, a woman whose uncle shot and killed himself, a former law enforcement officer whose brother was shot in a robbery in Colombia, and a man whose parents were shot at in Puerto Rico. Another participant described living in El Salvador during wartime and witnessing remnants of the fighting. One participant described having a gun pulled on him in a road rage incident. Two participants described knowing Marjory Stoneman Douglas students—the high school where the Parkland shooting took place—through their social networks, one woman described gun violence experienced by a coworker, one mother described an incident where her third-grade son’s classmate unintentionally shot and killed himself, and one woman described an incident where a neighbor attempted to shoot someone during an argument in his home. Finally, one participant shared that while he did not directly know anyone who had been a victim of gun violence, his cousin was currently incarcerated for shooting and killing someone.

For many participants, fears and frustrations about gun violence in the US also seemed particularly tied to their feelings that gun violence in this country feels random, indiscriminate, and ubiquitous. For example, one participant noted that she left Colombia during a civil war, but sometimes feels that she is “literally… more at risk here, because… there are no sacred spaces.”

Participants generally expressed that violence outside the US, in the countries that they or their families emigrated from, was tied to poverty, lack of economic opportunity, and the drug trade. However, most participants described that in the US, they felt like violence could strike anywhere. One woman described how, unlike in Colombia, in the US “nobody’s going to come and kill me because of a cell phone” or commit gun violence out of a need to “survive.” This same participant later shared how the unpredictability of gun violence in the US impacted her, saying she “just [doesn’t] go to concerts… it’s unpredictable because it’s like, yeah, not even churches, like you’re not safe anywhere.”

Frustrations about indiscriminate violence were also apparent when participants discussed school shootings, which they described as a phenomenon unique to the 50 states.

- “You don’t hear about school shootings in Nicaragua.” —34-year-old woman, born in Nicaragua

- “Here it seems to happen for no apparent reason. In a school, in a church. In my 59 years, I have never heard of a school shooting in Puerto Rico.” —59-year-old woman, born in Puerto Rico

- “In a first-world country, we turn on the TV every day and there are people being killed. There are children arriving at a school and being killed for the simple act of killing.” —57-year-old man, born in Venezuela

Some participants directly attributed the prevalence of indiscriminate violence to nearly unfettered access to guns in the United States. For example, one man shared that in his native Argentina “there are no semiautomatic weapons. That is why there are no mass shootings of so many people.” A woman from Nicaragua similarly noted that “the gun violence over there [in Nicaragua] is attached more to your political view. And here, the gun violence you see here, it’s more of the ‘anyone can have a gun.’”

Finally, a number of participants remarked that while violence in the places they or their families moved from was severe, they felt disappointment and sadness about the lack of safety in Florida. One person noted that her family “prefers [living here] over going back to the Dominican Republic, but they’re also very cautious and anxious living here as well.” Another participant, who left Puerto Rico after experiencing gun violence there, lamented that “being in the continental United States, well, for us we thought that we were going to feel a little safer, you know?”

Florida Latinos Have Diverse Views on Gun Ownership

The majority of participants in our sample were not gun owners and did not live in homes with guns, and gun ownership held different levels of value for various participants in our sample. In general, participants whose families had been in the US longer were more likely to express strong feelings that gun ownership and access were fundamental rights. One woman, born in the US but whose family emigrated from Cuba, made clear she was “for guns and gun ownership” and expressed that the right to gun ownership was important to her, saying “the sense of like, I have the ability to choose to have a gun, right? It’s not necessarily that I have to have it. It’s the ability that I can have it if I wanted to.”

More recent immigrants were less likely to frame gun ownership specifically as a “right,” and were more likely to express a narrower interpretation of the Second Amendment. One participant, for example, noted that when the Second Amendment was written “the cars ran on coal, then on gasoline, and today they are electric,” so needs for self defense may have changed. Another first-generation immigrant noted that while he agreed with the Second Amendment, it has now “gone beyond what it should be.”

These different attitudes among first-generation immigrants versus second- and third-generation immigrants may be explained by the fact that the Second Amendment is a uniquely American right that does not exist in other countries. One participant noted that “there’s a culture here where we have the Second Amendment and it’s considered that guns are a right. And that doesn’t happen in Mexico.” This participant further commented that attitudes towards guns are different in the US because in Mexico, “You grow up knowing that guns are for killing. They’re not seen as a means of defense. They’re seen as a tool to kill, to harm.”

Several participants similarly indicated that the stark contrast between strong US gun culture and the absence of such a culture in the countries they came from may motivate gun ownership for others in their communities. One participant noted that, “We have arrived at a culture where weapons are already a part of the culture. So, if [gun ownership] is a way of integrating into the culture and belonging, and feeling that we belong, and showing others that we belong, I think that can be a factor.” Another participant noted that Latinos were “running away from all that in our countries where we didn’t have them. And now we’re being sold the idea that we can have them and now we can protect ourselves.”

Importantly, in a slight contrast to attitudes towards gun rights, attitudes towards personal gun ownership—whether that involved owning or not owning guns—were related to family values and family protection for many participants. One participant expressed his conflicting views about how guns might both protect and endanger his younger siblings: “I personally have been going back and forth between should I [own a gun], not just to protect my family in general, but also I’m aware of the implications of what it might mean to have a gun in the house… If I do bring a gun into the house, is there potential for either of [my siblings], if they ever get to a low point in their life, to use that gun to take their life? … I’m constantly in-between two worlds of like I want a gun to be able to protect my family if anything were to ever happen, but also I know I have two teenagers, easily impressionable teenagers at home.”

In addition to family protection, many participants also talked about guns as something that people were using for self protection, particularly in light of increased hate-motivated violence and an increasingly armed public.

- “If everyone has a gun, how do I defend myself with a baseball bat?” —58-year-old transgender woman, born in Colombia

- “I’m carrying [a gun] again in my vehicle in case something happens. I mean, my behavior has changed. I look at people more cautiously, knowing I can be a target as a trans person, a public person.” —58-year-old transgender woman, born in Colombia

- “It’s not easy to go out knowing that if you say the wrong thing in the wrong place, four words in Spanish, they can attack you.” —57-year-old man, born in Venezuela

Although participants expressed different levels of interest and enthusiasm in owning guns and exercising gun rights, nearly all participants discussed guns themselves as being a threat to our democracy, suggesting that this community sees gun rights as being subordinate to other rights afforded to them in the US.

- “It weakens democracy. It does not allow for a dialogue and listening to others and for anyone to express their opinion.” —46-year-old woman, born in Mexico

- “Well, look at the incendiary comments from former President Trump and the number of followers he has, the QAnon, Proud Boys, and everything that happened after the Capitol. It seems to me that these days anyone takes out a gun and goes out to defend whatever cause.” —54-year-old man, born in Argentina

- “It would threaten our democracy, because I feel like when somebody has ownership of a gun, they feel like they have some sort of authority or power to decide on someone who doesn’t. I think that completely debunks the sense of democracy that we have, where everybody has an equal voice. For someone to own a gun and give them that sense of authority and power, I feel like it undermines what democracy should be.” —23-year-old man, born in the US and of Mexican and Guatemalan ancestry

STAND UP FOR SAFETY

Americans are not as divided as it may seem. Join GIFFORDS Gun Owners for Safety to stand in support of responsible gun ownership. We’ll share ways to connect with fellow gun owners and support our fight for a safer America.

Participants Believe More Could—and Should—Be Done to Prevent Gun Violence

Coupled with their concern about gun violence, participants expressed a unanimous anger, frustration, disbelief, and sadness that more was not being done to address gun violence in their state, community, and nation. Many participants expressed that when they heard gun violence discussed, either among their networks or in the media, the conversations were rarely oriented to solutions. As one participant put it, “I only hear things like how sad that someone got shot and circumstances happen, but nothing on prevention.”

Despite the lack of discussion about solutions, participants did not express fatalism about gun violence or describe gun violence as an intractable, unsolvable problem. In fact, all participants described various policies and ideas to reduce gun violence, with overwhelming agreement that gun safety laws in particular would help keep communities safer from gun violence.

Participants largely framed their desire for gun safety laws around policies that would require more training and education for gun owners, as well as policies that would make it harder for people in crisis or at increased risk of violence to access firearms.

- “It’s not about taking away the weapons, it’s about educating people to know how they should properly handle a weapon.” —57-year-old man, born in Venezuela

- “In Venezuela, to have a gun, as I recall, was extremely hard. You had to be part of an organization that, you know, you had to have a license with you at all times.” —53-year-old man, born in Venezuela

- “[I would like to see] a creative approach that still allows people to safely have guns, but keeps obviously, you know, firearms [away from] the people that don’t have the mental capacity or the training or have gone through any sort of screening to possess them.” —43-year-old woman, born in the US and of Cuban ancestry

Although our survey did not specifically ask participants why they felt these solutions had not yet been enacted, several participants shared thoughts about what it would take to implement solutions. Importantly, more than a third of participants (n=7) independently brought up the influence of the NRA as an obstacle to gun safety progress.

One former NRA member and current gun owner decried that “every time someone tries to educate [about gun safety], the NRA comes out.” Other participants believed that “NRA lobbyists’ powers are just beyond anything” and lamented that organizations like the NRA “make contributions to the different parties, to the different politicians, and then they do not dare to really do anything about it, to go against them, because they already have commitments. The commitment to an organization, for me, cannot be above the commitment to people’s lives.” These criticisms of the NRA were expressed by both US-born and foreign-born participants and participants that identified as Democrats, Independents, and Republicans.

Gun Violence Is an Important Voting Issue for Latinos in Florida

Nearly all participants shared that a candidate’s views on gun violence and gun policy would be important to them in voting.

- “It’s definitely at the top of my list. I think I have to see where you stand in terms of safety and guns and just all of that in general. It’s a very important part of choosing who to vote for.” —22-year-old woman, born in the US and of Dominican ancestry

- “It’s important because, because it’s something serious and it’s life and it’s costing us a lot and it could get worse. No, I haven’t seen any change yet, and so yeah, yes.” —58-year-old transgender woman, born in Colombia

- “When I see a person who is trying to regulate, who is trying for things to change, who is trying to eliminate violence, I’m in favor of that.” —57-year-old man, born in Venezuela

However, only a handful of participants could cite a specific instance where a candidate’s position on gun violence actually made them choose one candidate over another. One participant mentioned that Florida Governor Ron DeSantis’s pro-gun stance was “definitely a big factor in deciding not to vote for him at the previous elections,” saying that he didn’t “feel comfortable with a politician” who supported looser gun laws.

The disconnect from people’s statements that a candidate’s position on gun safety is important and them actually voting on this issue may be attributable to many participants’ beliefs that politicians did not make gun violence prevention a central issue in their campaigns or provide clear information about their plans to reduce violence. Participants also noted that gun violence sometimes gets lost when there are so many issues that matter to voters.

TAKE ACTION

The gun safety movement is on the march: Americans from different background are united in standing up for safer schools and communities. Join us to make your voice heard and power our next wave of victories.

GET INVOLVED

Latinos in Florida Want More Information and More Conversation about Gun Violence Prevention

While participants displayed substantial concern about gun violence and had ideas about gun policy, many participants also expressed that they did not know enough about this issue. In particular, participants often did not have a clear sense of how gun violence in Florida and Latinos compared to gun violence in other communities. Similarly, many participants expressed some confusion about how policies would work specifically. For example, although participants expressed support for policies that would ensure that guns do not fall into the hands of people that shouldn’t have them, some participants had questions about how a universal background check system would accomplish this goal, asking about what exactly would be screened.

Compounding the lack of knowledge was a near universal sense that information was not readily accessible—and in particular, that information was not provided in Spanish or tailored to the Latino community. For example, one participant noted that there was a nonprofit that provided information about immigration that was relatively accessible, but that their materials rarely touched on other issues impacting Latinos, saying that they talk “a little bit about the LGBTQ+ community, but the majority of these [are focused] on immigration laws,” and that she doesn’t “remember reading anything about weapons in them.”

Of note, one area where that was broad general knowledge among 70% of the sample (n=14) was about Florida’s recent adoption of a permitless carry law, which allows people to carry hidden, loaded guns in public with no background check and no training. All participants expressed strong views opposing this policy, believing that this law posed a threat to their personal safety, the safety of their families, and the safety of the entire community. In particular, participants expressed concerns that increased carrying of guns in public would promote more aggression and more intimidation and, in turn, more violence. Their awareness of this law is evidence that Latinos in Florida are interested in seeking out and consuming information about gun laws and gun violence in their state.

While participants expressed that they wanted to hear more about gun safety issues from political candidates and elected officials, there was also a sense that people wanted more discussion about and awareness of these issues within their own social networks and communities. Several participants talked about how they had initiated conversations about gun safety, particularly as it related to child safety. One parent talked about how she always shared that her home did not have firearms alongside pool safety information when having children over for playdates. She noted that she did this not just to promote gun safety but also to normalize a controversial issue: “It’s a difficult topic that nobody wants to talk about. And then if you do bring it up, you don’t know if you’re going to offend somebody, so I’m trying to normalize it that way.” Another parent similarly talked about how he initiated conversations about gun safety with other parents who expressed concerns about gun violence in schools.

Recognize the Diversity among Latinos as It Relates to Views on Gun Violence

This project found that there are a number of issues related to gun violence that likely resonate widely among Latinos—namely, a concern about gun violence, a desire for safer schools and more protections for children, and an appeal for a more solution-oriented approach to gun violence prevention.

However, there were also many issues where our participants expressed differing or converging views, such as on the salience of gun ownership as a right. These results affirm that the Latino community—including in the state of Florida—is not monolithic. Our results showed differences among foreign- versus US-born Latinos from different diasporas, participants of different ages, as well as other demographic characteristics. People working with the Latino community on gun violence prevention issues should ensure that they are taking into account the broad and diverse viewpoints its members hold.

Use Gun Violence as an Issue to Mobilize Latino Voters

Our research made clear that for these participants, gun violence is an issue of substantial concern—as well as one that many people feel impacts their day-to-day lives. Participants discussed how concerns about gun violence made them anxious to do certain activities or resulted in them avoiding some altogether. Those that had direct personal experience with gun violence talked about how these experiences continued to shape their lives even years after the event. And, critically, participants expressed an interest in learning more and hearing more about gun violence and gun violence prevention.

However, nearly all our participants believed that they did not have access to enough information about how gun violence impacted their community, what could be done to prevent it, and where different political candidates stood on gun safety issues. No participant believed there was adequate information available in Spanish. These findings make clear that organizations and political candidates in Florida should make gun violence a larger component of their outreach to the Latino community, especially by centering this issue around family values and family safety, which was a particularly important frame among our participants.

Invest in Further Research

While this project provides important insights into the diversity of perspectives held by Latino residents of Florida on guns and gun violence, more expansive study is needed to better understand these views, as well as the demographic and cultural characteristics that shape them. In particular, future research should work to identify the most persuasive messaging on the importance of gun safety policies and gun safety behaviors for different diasporas and generations of immigrants. Finally, given the differences between the Latino community in Florida and Latino communities in other states, more work should be done to understand how public education and messaging can be tailored by region.

This project demonstrates the diverse and wide-ranging perspectives that Latinos in Florida hold on gun violence, yet it also reveals a common truth: that we all believe a safer America is possible. But this future is not attainable without action—without political leaders who are willing to stand up for their constituents, without voters demanding accountability at the ballot box, and without communities being willing to have conversations about guns and gun safety.

Our project found that, overall, Latinos in Florida want to be part of this action, and it is now up to organizations, candidates, and advocates to truly engage these communities. This engagement must be genuine—we must recognize that the Latino community is not monolithic and that its members hold diverse and even conflicting views. We must provide tangible, actionable, and accessible resources—including in Spanish—for this community to learn about gun violence and its solutions. And we must realize that there is still more work to be done to understand the nuanced views of Latino voters and effectively reach and mobilize this community.

Through genuine partnership with these communities, we can live in an America free from gun violence. As one participant put it, “One moves here because of those freedoms… at least you have an opportunity. At least there is an opportunity for change, that is, there can be change. That is what matters.”

ELECTIONS

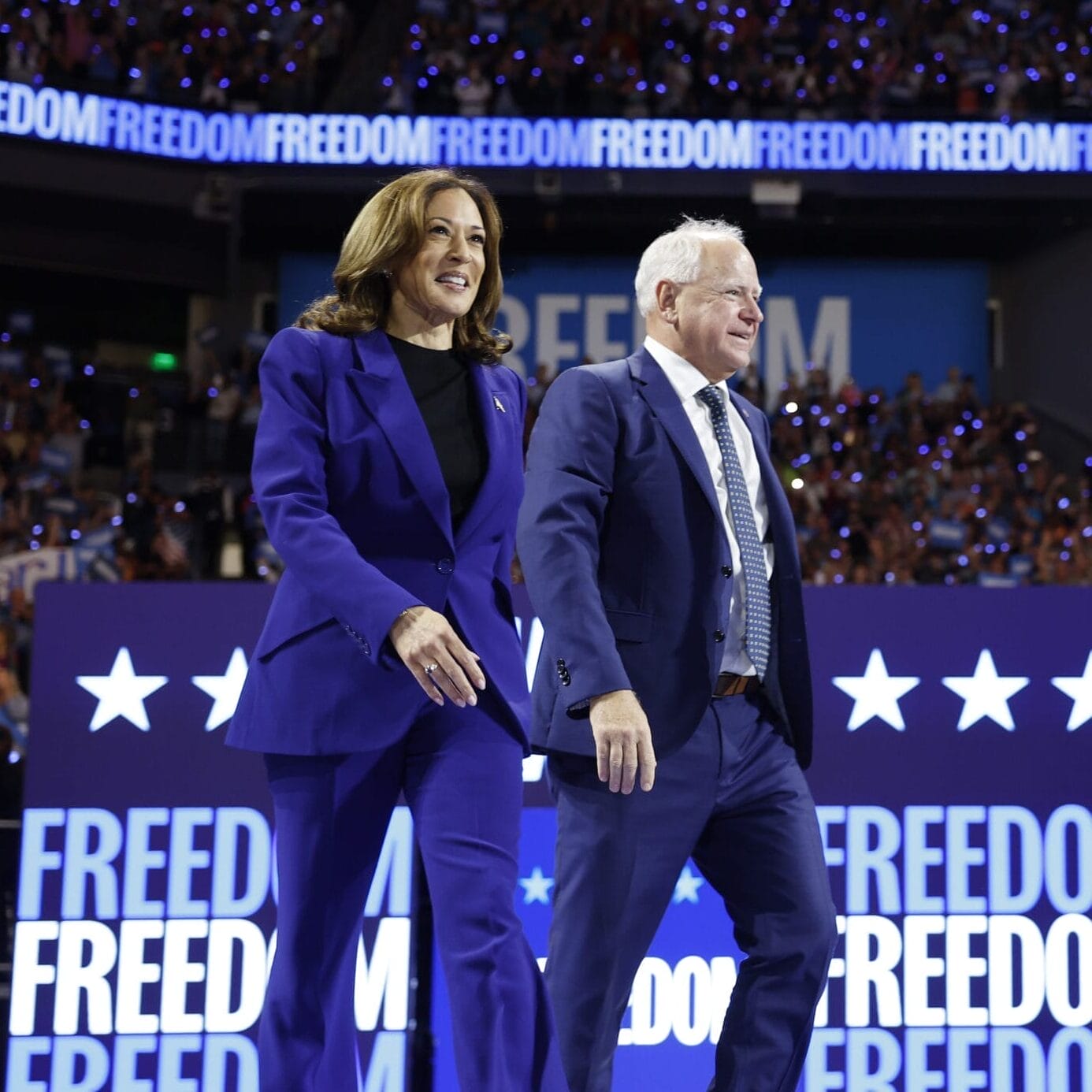

GUN SAFETY PRESIDENT

Kamala Harris and Tim Walz have demonstrated their commitment to fighting gun violence again and again, making gun safety a top priority in their campaign. We’re proud to stand with them in this must-win race, and we hope you will too.

Read More

GUN SAFETY LEADERS

Americans are demanding leaders who fight for us, not the gun lobby. Across the country, courageous leaders are running on gun safety platforms—and winning. We can’t let up now—we need to make our voices heard far and wide.

Join the fight- Antonio Campos, “What’s the Difference Between Hispanic, Latino and Latinx?,” University of California, October 6, 2021, https://www.universityofcalifornia.edu/news/choosing-the-right-word-hispanic-latino-and-latinx.[↩]

- US Census Bureau, “Explore Census Data,” last accessed August 28, 2024, https://data.census.gov.[↩]

- Id.[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- “2024 Florida Media Predict,” Televisa Univision, August 2024, available for download at https://hispanicvote.univision.com/states/florida.[↩]

- “2024 Florida Primary Election Profile,” NALEO Educational Fund, last accessed August 28, 2024, https://naleo.org/COMMS/PRA/2024/Florida_Primary_Profile_FINAL.pdf.[↩]

- US Census Bureau, “Explore Census Data,” last accessed August 28, 2024, https://data.census.gov.[↩]

- “2024 National Hispanic Voter Profile,” Televisa Univision, August 2024, available for download at https://hispanicvote.univision.com/datahub.[↩]

- “2024 Florida Media Predict,” Televisa Univision, August 2024, available for download at https://hispanicvote.univision.com/states/florida.[↩][↩]

- “Voter Registration — By Party Affiliation,” Florida Division of Election, last updated August 14, 2024, https://dos.fl.gov/elections/data-statistics/voter-registration-statistics/voter-registration-reports/voter-registration-by-party-affiliation.[↩]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (WONDER), “Underlying Cause of Death, 2018-2022, Single Race,” last accessed August 15, 2024, https://wonder.cdc.gov.[↩]

- One participant declined to answer this question.[↩]