Voices from the Ground: The Stories of Three Violence Intervention Workers

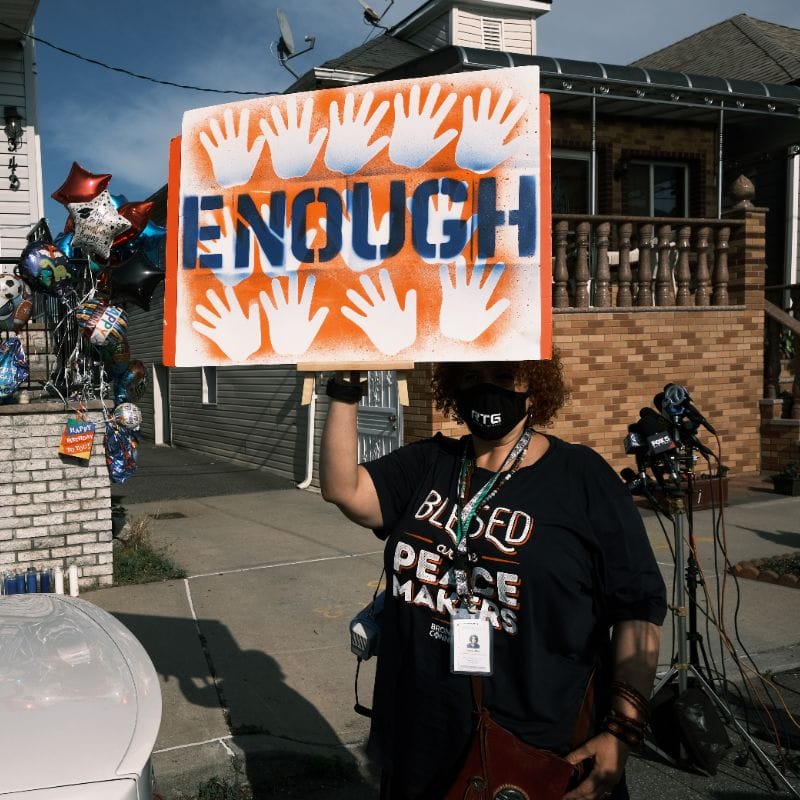

Community violence intervention workers play a critical role reducing gun violence, putting themselves on the front lines of tense situations to make their communities a safer place.

Many are formerly gang-affiliated and have painstakingly worked to change their trajectories. Now they’ve committed to helping others do the same.

But too often, CVI workers lack the resources to counteract the trauma and burnout they experience on a daily basis. Their jobs are emotionally draining and poorly understood by the public. A recent survey by Giffords found that 56% of CVI workers reported losing sleep due to stress stemming from work. That’s because the stakes couldn’t be higher—lives are on the line.

On any given day, CVI workers broker peace agreements between feuding groups, mediate interpersonal conflicts before they potentially escalate into shootings, and connect high-risk individuals with important social services to assist with transitioning away from dangerous routines.

At Chicago CRED, a gun violence prevention organization started in 2016, CVI workers embed themselves in some of the area’s most violently impacted neighborhoods. CRED, which stands for Create Real Economic Destiny, seeks to work with young men and women most likely to either get shot or shoot someone else. CVI workers are key to reaching this target population and encouraging them to enroll in the program.

Once that happens, participants receive therapy, job training, education, and life coaching over one to two years. CRED also provides a stipend to help participants meet basic living expenses as they work their way through the program without having to engage in illegal activities to support themselves.

The CVI workers are making a real difference. Over Memorial Day weekend, a notoriously violent period in Chicago, two neighborhoods where CRED is anchored saw zero shootings compared with more than 50 citywide. Northwestern University researchers also found that shooting rates of CRED participants dropped by 50% and their arrest rates for violent crime fell by 48% in the 18 months following enrollment in the program, according to a preliminary study.

For CVI workers, each success is hard earned. Here’s how three CVI workers at CRED describe their struggles, triumphs, and experiences on the job.

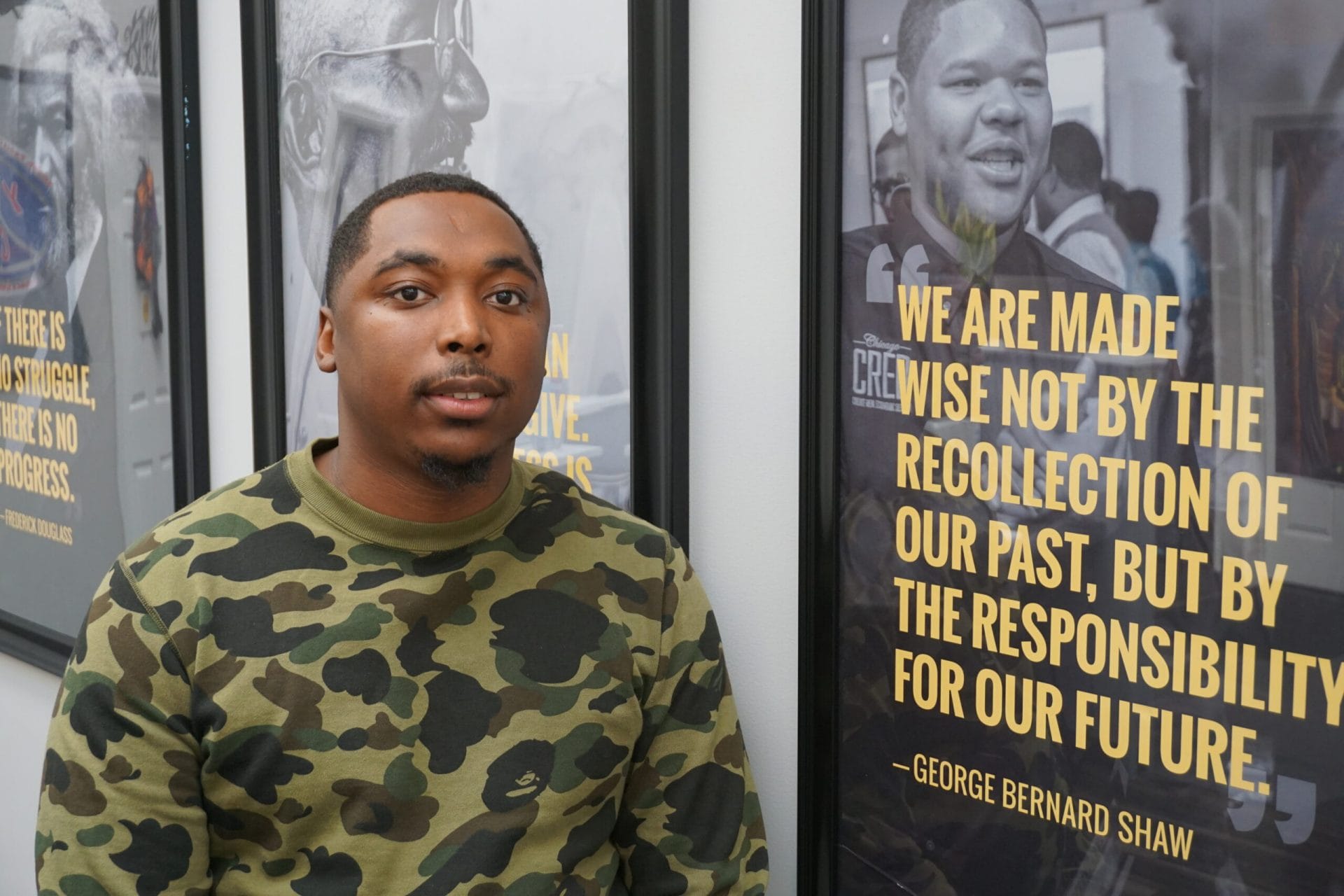

Dantrell Jelks, taken by Jamel Gardner, Chicago CRED.

When his shift ends at 10 p.m., Dantrell Jelks hops into his car and begins the cautious journey home. Before heading into his apartment for the night, the 28-year-old drives two laps around his block to make sure no one is following him.

It’s a practice Jelks describes as habitual—ingrained after years of running with gangs himself—but also necessary in his new career path. “We have to be aware at all times,” says Jelks, a case manager and recruiter with Chicago’s Youth Peace Center of Roseland, one of CRED’s community-based partners. “We can put ourselves in danger being out here if we don’t know what’s going on.”

Jelks understands both sides. He recalls learning as an eight-year-old boy what to do if someone shot up the house: lay down and cover your head, his older brothers, who were in gangs, told him. As a teenager, Jelks started getting involved with gangs, where he ascended the leadership ranks. He was shot at 15 while walking to a swimming pool with a group of friends and has gone to prison three times, all on weapons charges. In 2020 alone, Jelks lost three family members—two cousins and a brother—in shootings.

Source

Northwestern Neighborhood & Network Initiative (N3). 2021 (August 25). Reaching and Connecting: Preliminary Results from Chicago CRED’s Impact on Gun Violence Involvement. Institute for Policy Research Rapid Research Report. https://www.ipr.northwestern.edu/documents/reports/ipr-n3-rapid-research-reports-cred-impact-aug-25-2021.pdf

Still mourning their deaths, Jelks’s course changed after he enrolled in CRED—which is run out of Roseland’s Youth Peace Center. Now he’s recruiting for CRED, tapping the intel and relationships he forged in his past.

In his role, Jelks provides whatever support he can to help the men succeed. That could be answering a distressed late-night phone call from a participant who needs to be calmed down before making a bad decision, arranging housing for someone who’s lost a place to stay, or ensuring participants arrive at the center safely.

Some can’t take public transportation because they’re a target for retaliation, so Jelks uses his personal car to give them a ride. He also picks up teenagers from local high schools who are part of a parallel youth program geared toward intervening at an even younger age. Jelks works untraditional hours—2 p.m. to 10 p.m.—because the program aims to keep the men engaged during the evenings, when there’s a greater risk of violence occurring in the neighborhood.

But Jelks often worries about his own safety. It weighs on him that those rides, while a critical service for participants, also put him in harm’s way. Since he’s driving a regular, unmarked vehicle, someone watching him pick up a participant may not realize he’s with an anti-violence program.

“I can drop you off, go to the gas station and get my head blown because I just had you in my car,” he says. “It’s that easy. I’m guilty by association.”

On a recent afternoon, Jelks’s work phone lights up with activity as he sits in a conference room at the one-story center, where armed security guards screen guests upon entry. A session for the older men on trauma stress management is about to begin, but Jelks received a text message from someone saying his ride fell through. In the span of a few minutes, a younger participant also reaches out to say he needs transportation, so Jelks notifies his supervisor as he passes by.

Jelks grew up in Roseland, the South Side neighborhood where the center is located, but doesn’t live there anymore. Relocating to a different area has given him a sense of relief, he says.

“Being where you’re from is like real terror,” he says. “It’s stressful. You got to watch every second. Sometimes you want to let your hair down and be comfortable and at peace. But if I was still out here, I’d be on alert and gotta watch things.”

On the hard days, Jelks finds solace in his work. He still turns to his life coach from the program for guidance. This summer Jelks lost a fourth family member to gun violence—an 18-year-old cousin killed on his porch during a drive-by shooting.

He says he works through the pain.

“When I go through things, I come here,” he says. “This is my peace. The work is what I do to keep me at ease.”

Robert Hill, taken by Jamel Gardner, Chicago CRED.

As a youth life coach, Robert Hill works with one of the most vulnerable populations at CRED: boys as young as 11 and up to 17 who are already caught up in gang life. On some days, it can feel like he’s juggling multiple crises.

There’s the boy on his caseload who stopped showing up to school and has a strained relationship with his mother. The academically talented teen who brought a gun to school, concealed in his backpack for protection, and got arrested. The young man who’s grieving a friend fatally shot in the neighborhood.

“If I were to tell you that I didn’t feel burnt out sometimes, it would be a lie,” says Hill, 47. “I give so much.”

Hill has worked with adults in the program as well, but says his role with the youth is more challenging. They’re more prone to making rash decisions since their brains are still developing. They can also be more difficult to reason with, Hill says, and they engage in some of the most violent behavior.

“The youth are more of the hunters. They are triggered easily,” Hill says. “They try to prove themselves. They are willing to be more violent or aggressive than other groups are to prove they are not kids. It brings a scary dynamic to what’s going on.”

Much of the program focuses on Cognitive Behavioral Intervention, a form of therapy in which the participants learn to identify their emotions, better control their reactions, and de-escalate situations. Hill and other life coaches also provide mentoring and follow their performance in school, making sure the participants, who are all boys, not only show up but also remain engaged with class assignments. Participants whose grades or attendance slips have their stipends reduced or cut completely.

Along with the serious topics, CRED offers a safe space to unwind. Hill says he’s taken his groups on field trips to amusement parks, college campuses, and arcades. Many are out of state or hours away from Chicago to avoid running into anyone who might cause conflict. Nearly 50 boys are enrolled in the program and come to the center twice a week on different days.

“I really think that when we take them out of the area and they really get a chance to relax, you can see them turning back into kids,” Hill says.

Though the job is taxing, Hill says he feels it’s a calling. When it gets tough, he turns to exercise and counseling.

But he keeps doing it because he wants to give back to the community he harmed in his younger days, when he was involved with the criminal justice system.

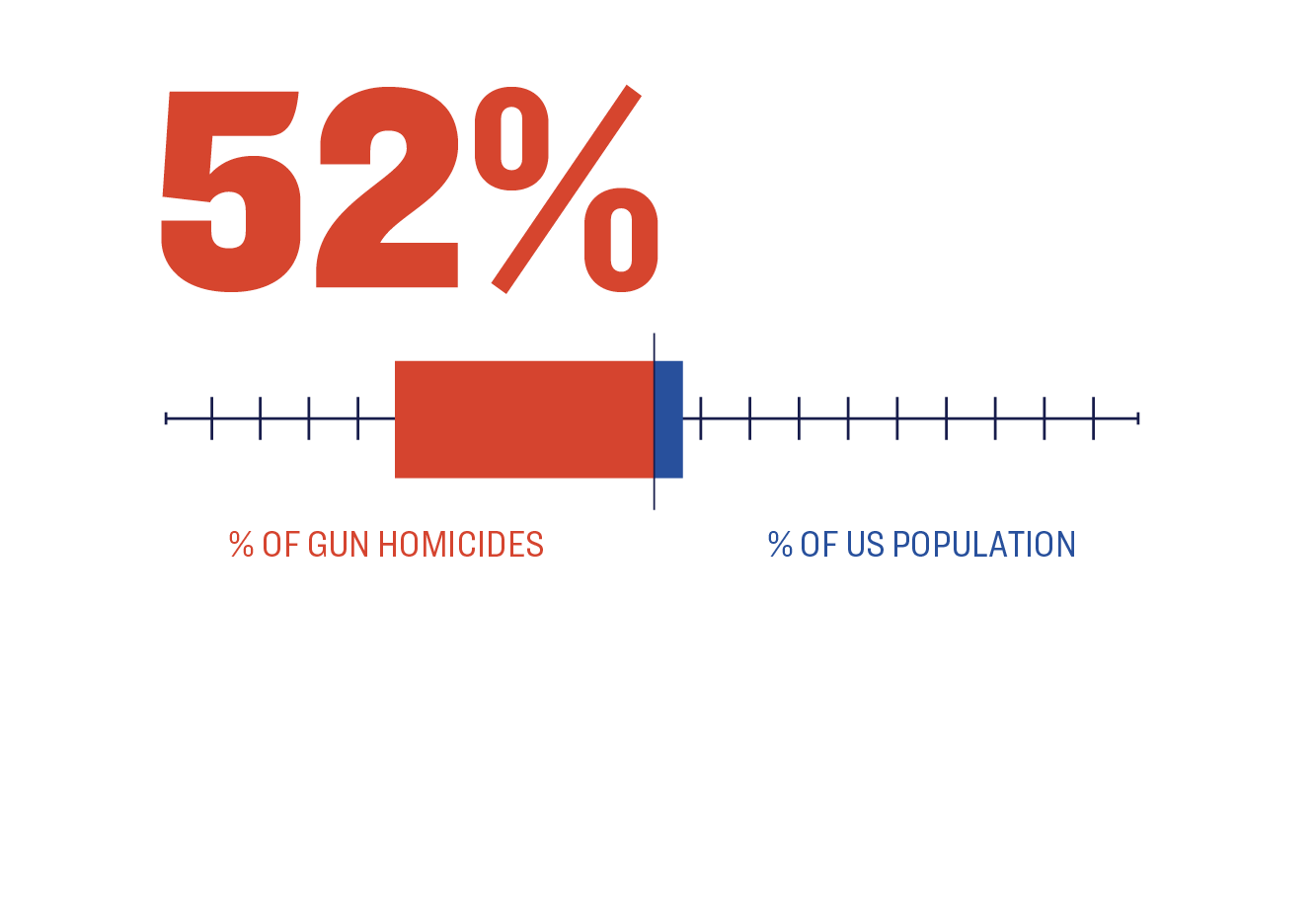

Over half of gun homicide victims are Black men

Source

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (WONDER), “Underlying Cause of Death, 2018-2024, Single Race,” last accessed February 25, 2026, https://wonder.cdc.gov/.

Hill grew up in the same neighborhood where he works now. His grandparents raised him while his mother struggled with drugs. Many of his relatives were part of gangs and sent to prison. At nine, he saw his uncle shoot his aunt’s boyfriend. Several years later, Hill shot a different uncle, who had gotten into a domestic dispute with Hill’s grandmother, and was sent to juvenile detention.

These experiences, Hill says, make him uniquely qualified to get through to the young men he now counsels.

“I know what these guys are facing because I literally went through this thing in my household. where my family was gang affiliated,” he says. “It was multiple men in the home. They were not really trying to set good examples.”

Above all else, Hill says he invests himself in the boys so they feel that someone cares. He picks them up and drops them off from school and is always a phone call away, at any hour of the day.

“I know these guys are fighting a battle of trauma. Of not being loved, or feeling they’re not loved, or feeling like they have to impress their friends,” Hill says. “We play a very important part even with sometimes parents not being available, or the relationship has been damaged. We try our best to make sure we’re there as much as possible. A lot of these guys just feel abandoned.”

Terrance Henderson, taken by Jamel Gardner, Chicago CRED.

Terrance Henderson got his start in violence prevention thanks to a local pastor’s basketball tournament. The competition, known as the “Peace League,” brought rival gang members—and even some NBA stars—together under a common interest in the summer of 2010. At the time, Henderson was employed by the pastor and responsible for bringing members of his crew to play. But the result was far more profound than anything Henderson could have imagined.

“Seeing that many oppositions in one room was like a lightbulb,” he says. “To actually see it work and see the violence go down in the area for some years because of what was going on with that basketball tournament was really instrumental.”

Henderson, now 38, has dedicated himself to preserving the peace ever since. He’s the manager of outreach operations at Chicago CRED, where he oversees recruiting efforts. Henderson and his team of outreach workers hit the streets every day to talk with business owners, groups of teenagers hanging around the block, and any other stakeholders who will listen about signing up. Henderson says he is selling hope: a chance for young men heading down a risky path to turn things around, get a decent-paying job, and leave the dangerous life behind.

“This is where everything gets started,” Henderson says one afternoon sitting in a small office at the outreach headquarters, a nondescript church building that he calls the Center for Transformation. “We are directly involving and entrenching ourselves in these guys’ trajectory. We have to go meet them where they are. We have to bring them to our facilities to receive programming. We’re the first contact.”

Henderson’s team also helps negotiate nonaggression agreements between feuding gang factions. When shootings occur, his team responds and checks in with people in the area once police leave the scene to help prevent further bloodshed and stem any retaliation.

Despite more than a decade of experience, the work still takes a mental toll on Henderson. As the head of recruitment for three program locations, Henderson personally interviews each young man who enrolls and assigns him to a facility based on his history—for everyone’s safety, CRED doesn’t want men with previous conflicts to be in the same building. He grows close with many of the participants, even those who don’t finish. Some get arrested and can’t continue. Others are killed in the gun violence they were trying to escape.

“You have to find something that keeps you grounded because you will get submerged in this work,” Henderson says. “There’s a lot of darkness that comes with it.”

Henderson says he finds support in his fellow outreach workers, who rally around each other in challenging times and go on group vacations together, as well as from the CRED therapists who work with participants.

“It’s a privilege to have all the clinical staff that’s there for the guys at our disposal,” he says. “We have a team of clinicians that we can speak to 24 hours a day. They are a phone call away.”

That’s helpful for someone whose own life has been shaped by violence. When he was four years old, Henderson’s father fatally stabbed his mother. His father then went to prison, so Henderson grew up with his grandparents, bouncing around different neighborhoods. His brother became a high-ranking member of a gang, and Henderson was also being groomed for gang leadership before he decided to take a different path.

Henderson opens up about his trauma in case it resonates with the young men he’s trying to help. Initiating that dialogue allows him to build trust and get insight into what might be driving some of their harmful behavior.

“The whole thing about outreach is being relatable,” Henderson says. “As soon as I hear what we can connect with, I’m going straight to that. A lot of these guys haven’t had one-on-one in-depth positive conversations with anyone. We’re not doctors, but we are saving lives and changing neighborhoods.”

STAY CONNECTED

Interventions are most effective when they are supported by strong community networks. Sign up for Giffords Center for Violence Intervention’s newsletter to learn more about what’s happening in the field, relevant legislation, and funding opportunities.