All Hands on Deck: The Role of Counties in Addressing Community Violence

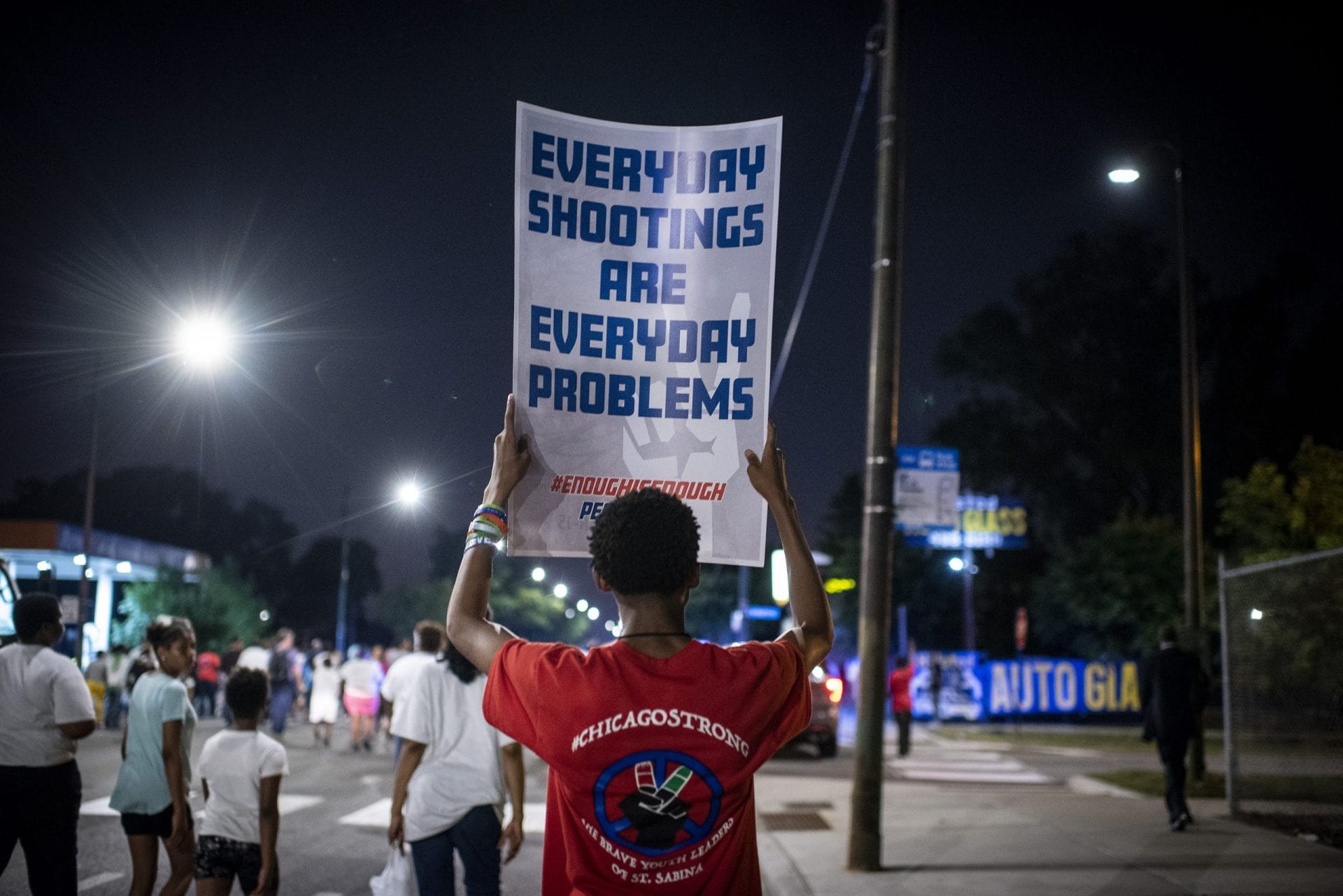

As the leading cause of death for children in the United States, gun violence is a public health epidemic that demands solutions.1 Among the biggest drivers of this crisis is the daily homicides and shootings that impact cities and communities across the country, typically referred to as community violence. This violence leads to the death and injury of tens of thousands of Americans every single year, and it disproportionately impacts communities of color.

Gun violence, and especially community violence, is a public health crisis at the intersection of poverty, systemic racism, housing insecurity, trauma, mental health, and education, among many other factors. That’s why, in order to properly address it, we need to use an all-hands-on-deck approach. This means we need engagement and support from all kinds of private and public stakeholders, at all levels of government—including counties.

When it comes to directly supporting effective community violence intervention (CVI) and prevention work, more and more cities and states across the county have begun to take meaningful action. For example, while this might have been unthinkable just a decade ago, there are now dozens of city-level Offices of Violence Prevention (OVP) with the explicit goal of supporting and expanding effective violence reduction strategies.

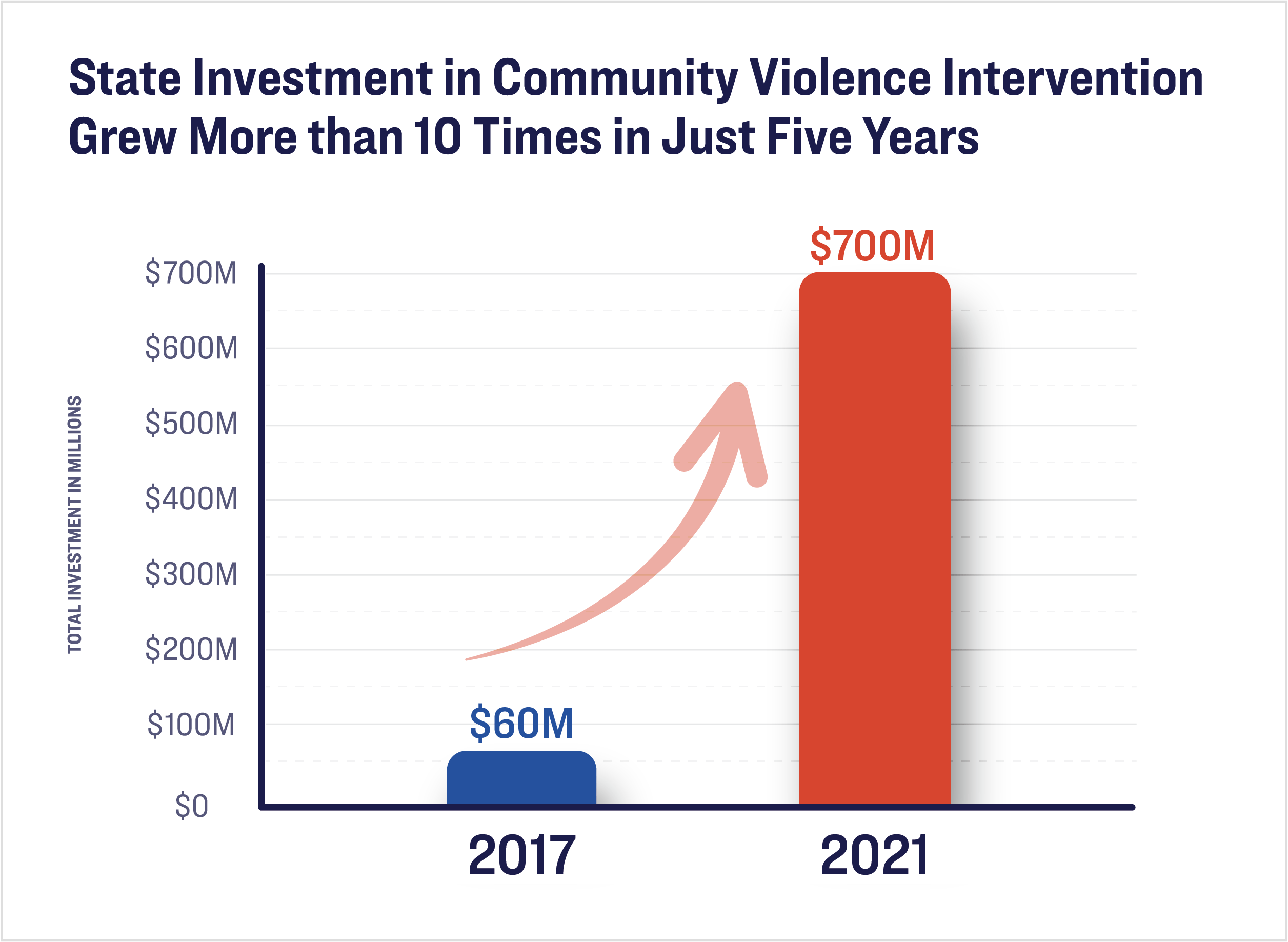

When GIFFORDS issued our 2017 Investing in Intervention report, only five states invested any funds to support community-based, public health approaches to reducing violence, with a total investment of just $70 million. That figure is now at least 15 states—with an overall investment of $690 million—as more and more states create statewide Offices of Violence Prevention and implement robust grant programs, such as the California Violence Intervention and Prevention Program (CalVIP).2

Dramatic change is also occurring at the federal level. In 2022 we saw a historic level of investment in community-based violence intervention and prevention programs, and in 2023 the White House launched its first-ever Office of Gun Violence Prevention.3 At the end of 2023, several US cities recorded their lowest homicide levels in decades, including Newark, New Jersey; Detroit, Michigan; and Richmond, California, among several others.4

However, despite progress at the city, state, and federal levels, most counties are still not actively supporting or otherwise investing in the development of an ecosystem of community-based strategies to reduce homicides and shootings.

This must change.

STAY CONNECTED

Interventions are most effective when they are supported by strong community networks. Sign up for Giffords Center for Violence Intervention’s newsletter to learn more about what’s happening in the field, relevant legislation, and funding opportunities.

County governments are a critical stakeholder in the fight against community violence for several key reasons. Because of their size and position above municipal government, county governments are well-positioned to incentivize and enhance the coordination between violence reduction efforts across multiple cities and to facilitate a regional approach to addressing violence, which often spills across artificial and invisible political boundaries. Moreover, various service systems that are critical partners for violence reduction efforts, such as public health, mental health, workforce development, healthcare, and child and family services, often sit within county jurisdiction.

County governments are also uniquely positioned to give assistance to geographic areas that are disproportionately impacted by homicides and shootings. In fact, in unincorporated areas, county government may actually be the only public entity in a position to implement violence reduction services. Additionally, county governments may have the resources to leverage and manage funding opportunities—such as federal grants—that are otherwise too resource-intensive for local entities.

County governments “have a specific responsibility in preventing violence and addressing trauma,” concluded the authors of a foundational document for the Los Angeles County Office of Violence Prevention, which was launched in 2019.5 “Government can also realign existing resources and work to generate new resources to support violence prevention efforts whether it is through the pooling of departmental resources to support programming in priority areas, responding to violence prevention funding opportunities from a variety of federal, state, and local sources, or supporting legislation that helps advance the field.”

Several trailblazing counties across the country are building out robust Offices of Violence Prevention and related programs and strategies to directly address community violence. First highlighted in our 2022 report Addressing Community Violence in St. Louis County, the efforts of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania; Harris County, Texas; and Los Angeles County, California each provide a model for how counties can invest in strategies to combat community violence.

Though these counties have unique political, demographic, and community violence dynamics, they have all made tremendous strides toward developing a comprehensive county-wide response to violence. Using updated information from our previous report, we identified four common elements that these counties—and others looking to address community violence—have prioritized:

- Data Collection and Problem Analysis

- Funding Evidence-Informed Intervention and Prevention Strategies in Disproportionately Impacted Communities

- Encouraging Coordination and Collaboration

- Capacity Building and Frontline Worker Wellness

This report summarizes the programs of each county before diving into the common elements and best practices. For more information about the efforts of these specific counties, please take a look at our 2022 report or reach out to us. It’s our hope that county leaders from around the country will be able to use this information to implement and expand effective community violence reduction strategies in their own jurisdictions.

Allegheny County, Pennsylvania

Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, where the City of Pittsburgh is located, has a total population of 1.2 million people. A detailed report on violence trends by the County Department of Human Services (DHS) showed that violence is heavily concentrated in just a small number of underserved communities—on average, homicides occur in just 0.3% of census blocks, with 79% of these blocks located in census tracts with moderate to extreme levels of need.

This violence disproportionately impacts the lives of young Black men. “Despite Black men making up only 6% of the County’s population, they are victims in 66% of annual homicides on average. Most of these victims are between 18 and 34 years old.”9 As is the case in most of the country, the vast majority of homicides in Allegheny County (86%) are committed with a gun.

“A very small percentage of at-risk young men in our higher-need communities are the most vulnerable to involvement with or victimization from gun violence, with social network analyses showing that most of these young men are acquainted with each other,” the DHS report found.10 “Most violence erupts as the result of ‘beefs’ between at-risk young men (arguments that are increasingly likely to start online) or is retaliatory in response to other instances of violence in the community, with at-risk young men of the belief that they are defending their life, the life of a loved one or their own reputation.”

Over the last several years, Allegheny County has suffered approximately 107 homicides annually. About half of those homicides occur in Pittsburgh. As with many localities, Allegheny County saw a large increase in homicides and shootings starting with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, with double digit increases between 2019 and 2021, creating increased pressure for local action to address community violence.

Community Violence Reduction Initiative

In response to this violence, DHS committed to establishing a comprehensive and coordinated Community Violence Reduction Initiative (CVRI) to deploy long-term resources and technical assistance to communities most impacted by violence.

DHS staff wanted to better understand what the department—the county’s largest, providing services to more than 200,000 residents—could do to more directly support local violence reduction efforts. As a starting point, recognizing that “efforts to reduce gun violence must be informed by data,” staff conducted an extensive analysis of homicide data from the Allegheny County Office of the Medical Examiner, supplemented with non-fatal shooting data from the Pittsburgh Bureau of Police.10

This analysis of data from 2016 to 2021 revealed several important facts about the nature and dynamics of community violence in Allegheny County:

- The majority of homicides are committed with a gun.

- There are five non-fatal assaults for every homicide.

- Serious violence is concentrated in a small number of geographic areas.

- Much of the violence is driven by interpersonal conflicts and cycles of retaliation.

- Young Black men in high-need areas are disproportionately both victims and perpetrators of community violence.

“It is important to note,” the DHS report concluded, “that our Black communities tend to have higher levels of need because of historical and contemporary racism in housing, lending and land use policy; the negative impacts of outmigration, white flight and urban renewal; disproportionate impacts resulting from deindustrialization and economic structuring; and the harmful ways in which government and other institutions have historically responded to public health challenges in Black communities (via punitive criminal justice policies and lack of investment).”11

The mission of the Community Violence Reduction Initiative is “sustainably funding public health approaches to community violence reduction that are rooted in evidence and well-coordinated.”12 CVRI has two primary elements: To direct support for violence reduction efforts within areas of the county most impacted by community violence, and to provide coordination and convening of stakeholders in those areas. This work is being funded at approximately $10 million annually, which comes from a combination of state and federal sources.

Direct Support for Impacted Communities

With its homicide and non-fatal shooting analysis, DHS found that violence in Allegheny County is highly concentrated in a small number of Pittsburgh neighborhoods, in several municipalities directly to the west and east of Pittsburgh, and throughout the Monongahela River Valley. Recognizing that Pittsburgh already had well-developed violence reduction infrastructure coordinated by the Pittsburgh Bureau of Police and the Office of Community Services and Violence Prevention,13 DHS leadership decided to focus support on the disproportionately impacted areas outside of Pittsburgh.

The data analysis helped identify areas of emphasis for this work, as did extensive conversations with stakeholders in the region, including frontline violence intervention and prevention practitioners, residents, law enforcement agencies, and others. These conversations began in early 2021 and continued throughout the year. Several key gaps emerged:

- Limited implementation of evidence-based approaches

- Grants to pay for community-led programs were not long-term or sustainable

- Lack of partnerships and information sharing between stakeholders

- Lack of focus on those at highest risk, particularly when it comes to wraparound services, trauma-informed care, and credible messengers

- Lack of capacity when it comes to building support and technical assistance for organizations doing the work on the ground

With those gaps in mind, DHS staff created a request for proposals to expand and coordinate violence reduction strategies in targeted communities. Knowing this was a big ask of local communities and that some of the work would be unfamiliar to certain stakeholders, DHS staff took the extra step of going out into communities to spread the word about the upcoming funding opportunity and give people time to prepare for it, ask questions, and distribute news of the opportunity within their own networks.14

The solicitation was formally released on January 5, 2022, with 12 eligible communities that “have not had the resources and infrastructure to create and invest in a coordinated strategy.” While no single strategy or organization can single-handedly stop community violence, the solicitation stated, “coordinated efforts rooted in evidence-based practices, sustainable funding, and solid infrastructure…have the potential to change a community.”10

“Coordination is key in all of this,” said DHS’s Nicholas Cotter, “so we built it in by saying that applicants needed to elect a community quarterback—an agency to oversee the implementation of the Community Violence Reduction Plan and be the fiscal agent for the whole project.”10

Based on a review of literature from the field, DHS required that applicants incorporate at least one of three evidence-based violence reduction models into its Community Violence Reduction Plan: 1) Cure Violence, which calls for credible messengers to intervene in violence and direct high-risk individuals to supportive services;15 2) Becoming a Man (BAM), which places full-time, highly skilled counselors in schools to guide young men as they learn, practice, and internalize social emotional skills;16 and 3) an adaptation of the Rapid Employment and Development Initiative (READI),an intensive 12-month initiative that works with high-risk participants and focuses on the core components of outreach, cognitive behavioral therapy, paid transitional employment, and life skills training.

The solicitation included a detailed overview of each of these models and the evidence behind them, as well as links to additional information. DHS also arranged for the developers of these models to present to potential applicants in a recorded webinar, to help familiarize potential applicants with the core elements of each.17

In addition to the three named evidence-based strategies, funding was also available to support existing violence prevention initiatives “that show results or promise,” as well as efforts to bring residents together to build safer and stronger communities, including events, performances, and youth mentoring.18

Finally, in recognizing the politically fractured nature of municipalities outside of Pittsburgh, DHS encouraged applicants to submit proposals that would cover multiple cities, “especially if a joint Proposal would amplify their ability to reduce violence,” and particularly in contiguous “eligible communities” that share the same school district.10 The solicitation also required applicants to demonstrate proof of multi-sector collaboration.

Source

Jason Corburn and Amanda Fukutome-Lopez, “Outcome Evaluation of Advance Peace, Sacramento, 2018–2019,” UC Berkeley Institute of Urban and Regional Development, March 2020, https://www.advancepeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Corburn-and-F-Lopez-Advance-Peace-Sacramento-2-Year-Evaluation-03-2020.pdf.

To allow communities and potential applicants sufficient time to prepare, DHS left the solicitation open for four months, longer than the usual window for a grant application. To minimize overlap and encourage maximum coordination, DHS required applicants to submit letters of intent two months into the application period, and then worked directly with applicants with overlapping proposals and encouraged them to submit a joint proposal. DHS also gave applicants access to planners for those who needed additional assistance.14

In the end, there were six applications submitted, with no overlapping areas of coverage. Applications were evaluated by a panel of approximately 12 individuals, a combination of DHS staff and staff from partnering agencies, community members with lived experience, and staff from the pre-selected model implementation organizations Cure Violence, BAM, and READI.

All local grantees are required to work with the Countywide Convenor, a contracted entity that oversees the coordination of all community violence reduction efforts across the county. The Countywide Convenor organization was selected through a parallel countywide solicitation process, and this role is described in more detail in the following section.

The Community Violence Reduction Initiative launched in January 2023 and DHS staff intentionally dedicated the initial phase of the initiative to building grantees’ organizational capacity before there was any expectation of documented results. During this time, grantees worked closely with Cure Violence Global, Youth Guidance (the developer of BAM), Heartland Alliance (the developer of READI), and DHS’s contracted Project Manager to adapt evidence-based programs to fit Allegheny County’s local context, refine budgets, engage in intentional hiring practices to identify qualified frontline staff and leadership, and complete intensive training facilitated by the model developers to ensure program fidelity, including site visits to see the models in action in other jurisdictions.

CVRI provides a clear model of how county governments can directly build the capacity of localities to address community violence in a coordinated fashion—especially in areas where resources for this work are lacking and where incentives may be needed to encourage politically fragmented municipalities to coordinate their efforts.

Countywide Support and Coordination for Violence Prevention

DHS staff and leadership also recognized the need to support and coordinate efforts at the countywide level, with an emphasis on the county’s unique role as convenor of local programs. On January 5, 2022, the county opened a solicitation titled “Countywide Support for Violence Prevention,”19 which funds four specific strategies.

Countywide Violence Reduction Convenor

The solicitation asked for applicants to serve as the Countywide Convenor, with qualifications including knowledge of the field of violence intervention and prevention; relationships with national, state, and local subject matter experts; a history of successful collaboration with entities ranging from law enforcement to community-based organizations; and the ability to work effectively with the evidence-based models of violence reduction.10

One of the main roles of the Countywide Convenor is to support the successful implementation of CVRI through activities including the coordination of information-sharing among stakeholders, disseminating best practices, and providing technical assistance. The County Convenor is also expected to identify needed policy changes at the county level and to conduct “the community organizing needed to make progress toward those changes.”10

The selected grantee began facilitating biweekly meetings with stakeholders and is currently in the process of developing a governance structure for countywide convenings that also takes into consideration opportunities for alignment and intentional coordination with other levels of government.

Shooting Reviews

DHS also sought applications from entities to implement shooting reviews for highly impacted jurisdictions across the county.20 The solicitation described shooting reviews as joint efforts between law enforcement, social services, and health service agencies to examine what drives gun violence locally and collect intelligence that frontline violence prevention staff may act upon to prevent future violence.

The entity carrying out the shooting reviews is responsible for establishing information feeds, including from social media and law enforcement sources, creating protocols for the collection and storage of relevant information, facilitating deliberation and problem solving with community-based organizations in priority communities, and tracking and publishing results.

During the early planning phase of the shooting review, it became clear that it would be challenging to coordinate a criminal justice–led shooting review across Allegheny County’s 100+ police departments.

Instead, in 2024, DHS and Social Contract will launch a Centralized Rapid Response Homicide and Shooting Review. The review will include a clearly defined group of proximate public health stakeholders, including frontline agencies responding to violence, with the following goals:

- To ensure a timely response to all shooting incidents

- To coordinate response and care between direct service providers

- To collect community violence data and identify trends

- To identify shared problems and develop proposed solutions

- To inform policy and systems change to contribute to violence reduction as applicable

DHS also worked closely with the City of Pittsburgh’s Office of Public Safety to design and launch a cross-municipal shooting response system in an effort to combat transient violence and prevent further retaliation across municipal lines.

Source

George, P. et al. (2022). Evaluation of a hospital-based violence intervention program on pediatric gunshot wound recidivism in Chicago. PREPRINT (Version 1) available at Research Square https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs1389582/v1

Hospital-based Violence Intervention Programs

The third category requested by the support and coordination solicitation was for at least one applicant to implement a hospital-based violence intervention program (HVIP) at a trauma center in the county. The HVIP model is based on providing comprehensive wraparound services to victims of violence, using credible messengers to connect with victims during their recovery in the hospital and working closely with them after discharge for a period of months in order to address underlying risk factors for violence, including retaliation, housing insecurity, and lack of economic opportunities.19

The solicitation required applicants to provide immediate services to victims of community violence, coordinate with other HVIPs in the county, and employ frontline workers with similar lived experience as the population most impacted by community violence.

Support Services for Survivors and their Families

The fourth and final category of the solicitation called for one applicant to “convene and provide resources” to groups of parents and survivors of community violence, including helping communities to create new support groups for survivors, providing direct support to survivors of violence in “communities without support,” and bringing together groups in order to organize projects and advocate for improvements.

Through a combination of direct support for localities outside of Pittsburgh, countywide convening, implementation of countywide strategies such as HVIPs, support for survivors and their families, and a formal shooting review process, DHS has created an innovative and robust initiative to address community violence.

Summary

There are several elements of the work in Allegheny County that merit close examination by local leaders around the nation that are grappling with community violence. These include:

- Using a public health approach to review homicide and shooting data to assess violence trends and dynamics and to coordinate response between frontline service providers.

- Emphasizing the geographic regions most impacted by homicides and shootings.

- Inter-departmental partnership.

- County-level coordination and convening.

- Direct and long-term support for evidence-informed violence reduction strategies.

- Intensive support to build local capacity to address violence through training and technical assistance.

- Community input at all stages of the solicitation design and rollout process.

DHS is currently in the process of designing an ideal internal staffing structure—that is not overly bureaucratic—to manage CVRI in the long-term. DHS is also reviewing violence prevention offices from other jurisdictions to inform the expertise and level of capacity required to successfully oversee these community-based violence intervention, prevention, and coordination efforts. One such effort is located in Harris County, Texas, which is discussed next.

Harris County, Texas

Harris County is located in Southeast Texas along the upper Gulf Coast and includes the Houston metropolitan area.21 With 4.7 million residents, it’s the third most populous county in the nation,22 and the largest in the state.21 The county encompasses more than 270 towns, places, and municipalities, and over a thousand local governments.10

Community violence in Harris County is concentrated primarily in Houston, where more than 70% of all homicides in the county take place.23 This violence disproportionately affects Black and Latino communities, who make up a combined 64% of the total population but account for 86% of homicide victims countywide.24 Very few victims of homicide are under the age of 18; nearly two-thirds of homicide victims in the county are between the ages of 18 and 39, while just 8% are 17 or younger.10

Over the last decade, violence in Harris County has intensified substantially, with homicides more than doubling between 2011 and 2021. Much of this increase occurred at the height of the pandemic, as most major cities experienced a rapid increase in shootings and gun deaths. Between 2019 and 2021 alone, homicides in Harris County rose 47%.

The Division of Community Health and Violence Prevention Services

In response, the Harris County Commissioner’s Court directed county departments to explore developing a violence prevention program and a civilian emergency response model as a complementary alternative to law enforcement. After an extensive analysis of crime and hospital data, the court voted to allocate $2.9 million to establish the Division of Community Health and Violence Prevention Services (CHVPS) within the Harris County Public Health (HCPH).25 Commissioners also approved $6 million in one-time funding to launch violence interruption programs housed within the new division.26

Harris County’s Division of Community Health and Violence Prevention Services oversees two programs:

- The Relentless Interrupters Serving Everyone (RISE) program (formerly Community Violence Interruption Programs), which provides outreach and hospital-based intervention to individuals at high risk of using or being injured by a gun.

- The Holistic Assistance Responder Team (HART), which dispatches behavioral health workers, social workers, and emergency service personnel to respond to 911 calls that don’t require a typical law enforcement response.

The RISE program is described in greater detail below. More information about HART is available on the CHVPS website.27

2025 CVI CONFERENCE

Giffords Center for Violence Intervention will host the 2024 Community Violence Intervention Conference in Los Angeles on June 16 & 17.

Learn More

The Relentless Interrupters Serving Everyone (RISE) Program

Identifying the Most Impacted Areas and Individuals

Prior to launching RISE and CHVPS, the county Justice Administration Department (JAD) partnered with technical experts to conduct an analysis of violence in Harris County. The Health Alliance for Violence Intervention (the HAVI) and Dr. Chico Tillmon, director of the CVI Leadership Academy at the University of Chicago, worked collaboratively with JAD to review 10 years of violent crime data and assess the trauma registries of the county’s two Level 1 trauma centers. They also conducted numerous interviews with subject matter experts, community leaders, medical providers, and organizations providing services to the most impacted residents.28

Guided by this analysis, HCPH and CHVPS identified several neighborhoods with high rates of violence. RISE was piloted in the Sunnyside, South Park, and Greater OST/South Union areas of Houston, as well as the Cypress Station neighborhood in northwest unincorporated Harris County. According to HCPH and the CHVPS, these areas had high rates of gun violence, as well as “other risk factors such as high unemployment, poverty, low educational attainment, a lack of access to health care, safe housing and healthy food.”29

Through their review of hospital data, partners were also able to identify which hospitals provided the most medical care to victims of violent crime. This led to the selection of Ben Taub Hospital to pilot the HVIP component of the county’s violence interruption program.30 In the summer of 2022, Harris County Public Health was also approached by HCA Northwest in the Cypress Station area to bring HVIP services to their hospital.

Implementing Community Outreach and Hospital-Based Violence Intervention Programs

Community violence intervention strategies rely on credible messengers, native to the most impacted communities, who share similar lived experiences with the individuals they serve. These individuals work tirelessly to diffuse potentially deadly conflicts and connect people with services and support.31 In Harris County, these credible messengers are referred to as “outreach specialists” and are at the core of Harris County’s violence intervention program.

Source

Purtle, J., et al. (2015). Cost-benefit analysis simulation of a hospital-based violence intervention program. American journal of preventive medicine, 48(2), 162–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2014.08.030

RISE was designed to reach people at highest risk for committing an act of violence or suffering a violent injury by engaging them in the hospital setting and through community outreach. Both components of this strategy center outreach specialists.

The community outreach component of RISE relies on these messengers, trained in conflict resolution and mediation, to identify and intervene in situations that may lead to violence. RISE community outreach workers must understand the area, build rapport with high-risk individuals, and work to establish trust. Harris County outreach specialists are on call 24/7 to mitigate conflicts in real time.32

The county’s HVIP program is housed in the emergency rooms at Ben Taub and HCA Northwest hospitals, where credible messengers are deployed to engage with people recovering from a violent injury.33 Research demonstrates that people victimized by violence are at very high risk for reinjury and future involvement in violence, with the chances of injury recidivism as high as 45% within the first five years.34 When credible messengers are present in emergency rooms and trauma centers, they are able to meet with victims, their families, and social networks, and can intervene to prevent retaliatory violence.

As of November 2023, an estimated 170 clients had received HVIP services through the county’s efforts.35

In both the community outreach and hospital programs, credible messengers draw on their lived experiences and training to connect and build relationships with those most impacted by violence. In doing so, they are able to connect individuals with case management teams that can provide individualized support and resources to meet the unique needs of program participants.

Addressing Root Causes of Violence with Coordinated Supported Services

After the highest-risk individuals in Harris County are engaged and develop a rapport with HVIP and community outreach teams, outreach specialists assess participants and connect them with violence intervention and support services.10 Those with multiple or compounding needs are directed to Accessing Coordinated Care and Empowering Self-Sufficiency (ACCESS) Care Coordination teams.

The ACCESS initiative was launched by Harris County Public Health in 2021 with the goal of improving coordination and service delivery to county residents. The initiative is described as a “no-wrong door approach” that aims to break down silos and coordinate care across social service agencies and community-based service providers in the county. Violence prevention is a focus area for ACCESS, which collaborates with RISE community outreach specialists to provide wraparound services to individuals in need of support.

To help integrate services with ACCESS and expand the RISE program, Harris County applied for the Community Violence Intervention and Prevention Initiative (CVIPI), a newly established federal grant program administered by the Office of Justice Programs (OJP) within the Department of Justice (DOJ). On September 9, 2022, the DOJ announced that it would provide $100 million in awards to community-based organizations and local governments to implement and expand violence intervention efforts, including almost $2 million for Harris County.36

With this additional funding, ACCESS Harris Care Coordination teams will work with community outreach specialists in the county’s violence interruption programs to develop coordinated care plans for participants. Through ACCESS Harris, participants will be able to more easily connect with housing, reentry, behavioral health, employment, medical, educational, economic, and food assistance.

Engaging the Community

Harris County’s Public Health Department began community outreach and engagement efforts in January 2022 with the goal of sharing information, answering questions, and soliciting feedback about the newly formed Division of Community Health and Violence Prevention Services (CHVPS), including RISE.37 HCPH conducted numerous meetings in RISE focus areas and included a wide variety of stakeholders, including residents, survivors, service providers, and elected officials. In Southeast Houston, these meetings have evolved into hybrid community engagement meetings that help stakeholders stay connected and informed.

In addition to these community stakeholder meetings, the county plans to spearhead more public education campaigns, provide information about post-shooting vigils, and proactively communicate clear messages about alternatives to gun use. HCPH has launched a county-wide violence prevention campaign that involves billboards, public service announcements, and television ads in English and Spanish.

Summary

Though Harris County’s violence interruption programs are relatively new, since implementation, the county has taken several promising steps in line with national best practices. From the start, the county solicited technical assistance from experts in the field of community violence to develop and implement a countywide violence intervention program. CHVPS staff used available crime and hospital data to focus services on the populations with the greatest need. CHVPS staff also partnered with other public agencies and community organizations delivering on-the-ground services, among other key stakeholders.

Harris County staff worked to break down silos between system and community-based service providers by launching ACCESS Harris, an initiative to connect people with various behavioral health needs to individualized support services via community care teams. The county also launched a community engagement campaign to ensure the community can provide input and feedback as it continues to expand and develop.

Continuing community engagement, adequate funding, and ongoing data collection, analysis, and evaluation will be key to ensuring progress, but the county is off to a promising start. In a relatively short period of time, Harris County has made important strides and is an example to other counties seeking to develop violence intervention and prevention programming.

The third and final case study of this report comes from Los Angeles County, where community violence has dropped significantly in the wake of the COVID-19 surge.

Los Angeles County, California

Los Angeles County is the nation’s most populous county, with more than 10 million residents. Comprising 88 incorporated cities and many unincorporated areas within a total area of 4,083 square miles, it is home to more than a quarter of Californians and is one of the most ethnically diverse counties in the nation.

When staff at the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health (LADPH) looked at countywide data, it became clear that violence was disproportionately impacting a relatively small number of areas and that “people of color and people in communities that have borne the brunt of poverty, divestment, and racism are disproportionately impacted by violence.”38 According to provisional data for 2022, for example, the homicide rate among young Black men ages 15 to 29 in Los Angeles County was 12 times higher than the overall county rate.39

In 2015, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors, recognizing the need to fund a public health–based and trauma-informed approach to violence reduction, voted to allocate $2 million annually to the Trauma Prevention Initiative (TPI) within LADPH. The purpose of TPI is to provide violence intervention and prevention services in four unincorporated areas of Los Angeles County with disproportionately high rates of community violence, as well as other health and social inequities.40

TPI is a key component of what would become Los Angeles County’s Office of Violence Prevention (OVP), and it continues to be a cornerstone of the OVP’s strategic plan to reduce violence in the county.

Trauma Prevention Initiative Overview

TPI has three core elements: intervention, prevention, and capacity building for communities and community-based organizations.

Intervention

The first prong of the TPI strategy is to intervene with the small number of individuals at highest risk of engaging in violent behavior.41 This is done through contracts with community-based organizations that provide violence intervention services, including street outreach and violence interruption services and hospital-based violence intervention to survivors of shootings and stabbings.

Through a contract with Southern California Crossroads, TPI was able to provide case management services for more than 1,050 victims of violence at county trauma centers St. Francis Medical Center and Harbor UCLA Medical Center from 2017 to 2022.42 During the first six years of HVIP implementation, TPI communities served by these two hospitals saw a “9% reduction in assault-related trauma hospital visit rates, compared to a 3% increase in the County overall.”43 Moreover, there was a reduction in the number of overall Los Angeles County violence-related trauma patients coming from the four TPI communities. In 2021, LADPH was able to expand TPI’s intervention services to Pomona Valley Hospital, in partnership with Crossroads, and to Los Angeles General Medical Center, through a contract with Soledad Enrichment Action (SEA).

As part of its intervention portfolio, TPI also funds community-based organizations, including the BUILD Program, HELPER Foundation, Inner City Visions, Just Us 4 Youth, SEA, and Crossroads, to provide street outreach and violence interruptions services. This work engages credible messengers—individuals with lived experiences that give them unique access to high-risk populations—to provide services ranging from safe passages to and from schools to direct conflict mediation and peacekeeping.

Between 2018 and 2023, county-supported street outreach workers responded to more than 1,000 incidents of violence in the four original TPI communities, including 438 shootings and 268 homicides.44

LADPH staff also contracted with an evaluator to develop tools to help contracted organizations measure and understand their impact on public safety and community wellness, including the creation of mobile software for tracking client interactions and other work in the field.

Prevention

Another prong of TPI is supporting prevention-oriented public safety solutions that are informed by survivors of violence and residents of impacted communities. To achieve this, TPI leads helped establish local Community Action for Peace (CAP) coalitions in each of the TPI neighborhoods. CAP coalitions serve as a central hub to bring together residents to “celebrate positive community identity, foster collaboration, and identify priorities to prevent violence and promote peace and healing.” TPI’s street outreach workers and other community partners play a leadership role in these networks.

With community input, TPI leads also developed a priority list of prevention-oriented programming to address the root causes of violence and complement violence intervention efforts. For example, many community members identified park safety as a pressing need and, in response, TPI worked with other county entities to support and fund various programs designed to improve safety and create access to park spaces.

They also worked with the Los Angeles County Department of Parks and Recreation to bring its Parks After Dark program to more than 10 parks in TPI communities, where county departments and community agencies provide free family programming and services during the evening hours of 6 pm to 10 pm. This program includes fitness, wellness, and educational workshops, as well as access to fresh and healthy food.45

The Parks Are Safe Zones campaign was an additional park safety initiative created by TPI street outreach workers and community leaders to reclaim parks as a safe space for community connection and engagement.

In recent years, TPI has also funded mini-grants to support community priorities, including the distribution of personal protective equipment during COVID-19 and the implementation of a healthy manhood program, as well as training in trauma-informed practices, mentorship, murals, arts programs, and unity events to promote peace.

Capacity Building

The TPI Advisory Committee was created to foster regional community self-agency and to align county initiatives to focus support and resources in TPI communities. Since 2017, LADPH staff have brought together nearly 200 individuals and dozens of organizations representing a cross-sector group of county partners and TPI community providers. This group has collectively advocated for systems change, including increased collaboration between county departments to address the root causes of violence, establish safe public spaces, and increase resources for workforce development, healing arts, and youth development programming.

TPI leads also recognized early on that there was a “need to invest in local grassroots organizations that have strong ties to the community, in order to effectively address violence and trauma.”42 They launched a Training and Technical Assistance (TTA) Pilot Project in 2017, which involved contracting with four consultants with expertise in areas including nonprofit management and board development, data collection, grant writing, and program evaluation, as well as branding, marketing, communications, and website development. The consultants provided 45 capacity building workshops and nearly 1,600 hours of one-on-one training and technical assistance to 260 individual participants representing approximately 30 grassroots organizations within the four TPI areas.

According to an LADPH report, about 50% of these organizations “advanced to the next stage of organizational development, and 90% of agencies agreed that the TTA helped them function more efficiently.”10

TPI Results

In 2022, the National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO), recognized TPI with a national “model practice” award, noting that “TPI is built on [a] collaborative and comprehensive approach that centers those most impacted in the design and delivery of services, which is fundamental to TPI progress and achievement. TPI community engagement is based on the principles of equitable engagement including collective decision making, shared power and mutual respect.”

Between 2016—when TPI first launched—and 2023, homicides in the original four TPI communities declined by 30%, and gun-related aggravated assaults declined by 9%.42 The two TPI communities with the most significant reductions were those with the longest-running CAP coalitions. Moreover, between 2016 and 2022, the overall number of assault-related hospital visits declined by 9% in TPI communities, compared to a 3% increase in the county as a whole.44 TPI is estimated to have saved the county $1.9 million per year between 2016 and 2019 in terms of reduced criminal justice costs alone—and likely much greater when considering health system savings and benefits to individuals.10

The encouraging early experience with TPI became a springboard from which the Los Angeles County Office of Violence Prevention was able to build out a more expansive and comprehensive approach.

CONVERSATIONS WITH EXPERTS

GIFFORDS Center for Violence Intervention’s webinars explore different aspects of community violence through conversations with experts.

WATCH NOW

The Los Angeles County Office of Violence Prevention

As is often the case in the US, a tragic mass shooting spurred leaders in Los Angeles County to reassess their response to gun violence.

The shooting at Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida—one of the deadliest school shootings in US history—created a catalyzing moment for action in early 2018. In response to the shooting, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors passed a motion directing LADPH and the Chief Executive Office to “work together to create an Office of Violence Prevention within the Department of Public Health that will initially be tasked with coordinating the County’s various violence prevention efforts, and lead the County in a violence prevention strategic planning process.”10

Establishing a single office to coordinate the county’s response to violence, the motion explained, would help the county identify gaps in its violence reduction strategies and would also “be a first step towards the County’s adoption of a more strategic approach to preventing gun violence.”10 The motion instructed LADPH to work with various other county agencies and stakeholders to create a report to the board that would include an outline of the basic functions and staffing needs of an Office of Violence Prevention.

This culminated in a report LADPH presented to the County Board of Supervisors in June 2018, which included a landscape analysis of 25 different localities with offices of violence prevention and similar local programming.10 This analysis identified nine of the most common functions served by local offices of violence prevention:

- Standardizing data collection across city and county departments, programs, and community-based organizations.

- Coordinating multi-sector implementation of violence prevention initiatives.

- Creating centralized touch points of engagement for community members.

- Integrating community resiliency strategies within an overall framework.

- Building networks for community outreach.

- Supporting street outreach teams as an important tool for interrupting community violence.

- Engaging community members as peer mentors and advocates.

- Building trust between police and affected communities.

- Improving outcomes for young people at the highest risk of violence.

The report recommended the creation of an Office of Violence Prevention with a $3 million annual budget, nine staff members, and core functions including coordination of countywide violence prevention efforts, alignment of funding sources, data collection and surveillance, support for community-based violence prevention and intervention organizations, and responsibility for overseeing the creation of a five-year countywide strategic plan to address violence.

On February 19, 2019, the Board of Supervisors unanimously approved a motion to establish the Office of Violence Prevention (OVP) within LADPH and allocated $6 million to support the first two years of OVP operations.46

One of the first tasks for OVP staff was to convene a County Leadership Committee, consisting of department heads and staff from 30 different county departments, and a Community Partnership Council,47 including 25 individuals representing diverse geographic areas, demographics, and experience with different forms of violence, including survivors.48 These advisory bodies continue to meet every other month to help guide the implementation of the strategic plan, hold OVP accountable for meeting its objectives, and help coordinate violence prevention efforts by serving as liaisons to various community networks and initiatives.

To create the five-year strategic plan, OVP gathered input from the County Leadership Committee and the Community Partnership Council, and also contracted with the Prevention Institute to gather community and stakeholder input by conducting resident listening sessions and interviews with subject matter experts.49 In addition, OVP contracted with a consultant to facilitate the strategic planning process and assist with development of the plan. This process lasted several months and culminated in the 2020 release of the OVP’s Early Implementation Strategic Plan, 2020–2024.50

The strategic plan lays out the overarching mission of OVP: “To strengthen coordination, capacity and partnerships to address the root causes of violence, and to advance policies and practices that are grounded in race equity, to prevent all forms of violence and to promote healing across all communities in LA County.”51

Of particular note is the strategic plan’s clear-eyed assessment of the nature of violence in Los Angeles County. “People of color and people who live in communities that have borne the brunt of racism, are disproportionately impacted by violence,” the report states.11 As a result, there are two very concrete policy implications woven throughout the strategic plan. The first is prioritizing addressing racism and systemic violence. The second is tailoring prevention and intervention strategies to disproportionately impacted communities.

The strategic plan lays out five priority areas that each have multiple concrete objectives for OVP and its partners to implement:

- Supporting Children, Youth, and Families

- Creating Safe and Thriving Neighborhoods

- Fostering a Culture of Peace

- Implementing Healing-Informed and Equitable Systems and Policies

- Community Relevant Shared Data and Evaluation Support

The strategic plan also included an accountability system to measure progress, consisting of a series of two-year and five-year milestones and performance measures. For example, one of the milestones is establishing regional coalitions within each of the county’s eight Service Planning Areas, and the performance measures for this milestone include the number of coalitions established, the diversity of stakeholders, and both the quality and frequency of stakeholder engagement.

Finally, to assess the impact of its work, the strategic plan calls for OVP to collect and assess basic quantitative data, including homicide rates; emergency visits for assaults, suicide rates, and other violence-related data points; and population impact indicators such as reductions in violence, increased perceptions of safety, reductions in disparities, process indicators including the number of stakeholders engaged, and coordination indicators like increased alignment of funding streams to address violence and implementation of joint department policies or protocols.

OVP Implementation

As of April 2024, OVP is nearly through its five-year strategic plan and has been making progress on implementing the goals and objectives identified in the plan, which include the six implementation priorities outlined below.

1. Open Data Portal with Culturally Relevant Information

At present, OVP uses a variety of data sources to understand the dynamics and impact of violence in the county, including crime data, hospitalization/emergency department visit data, and coroner/death certificate data. OVP also coordinates the Los Angeles County Violent Death Reporting System (LAC-VDRS), a CDC-funded national data surveillance system, to monitor local violence trends and dynamics. This system provides important data about the circumstances of violent deaths and connects multiple deaths that occurred in a single incident. These and other data collected by county and community partners are critical to inform policymakers, but are not readily available to the public in an easy-to-use format.

OVP staff is working to create an “Open Data Portal,” drawing from LAC-VDRS but also other data sources, that would make violence-related data available to the public in a way that is easy to access, understand, and act upon. “This will include quantitative data about violent crime numbers, trends, demographic and geographic patterns, and risk factors, as well as qualitative data that will measure community member’s perceptions of safety, community priorities when it comes to addressing violence, and an assessment of community assets.” The open data portal will also include metrics to show the impact of OVP programs, including TPI, and is set to be launched in 2024.

2. Establishing Regional Violence Prevention Coalitions

Given the considerable size of Los Angeles County, with more than 10 million residents, it was important for OVP to establish local coalitions in each of the county’s eight Service Planning Areas to support local priorities and violence prevention efforts. In line with the five-year strategic plan, OVP has issued competitive contracts to lead agencies in each Service Planning Area to convene local stakeholders to help create a local Community Action Plan for each area.41 These contracts, each approximately $150,000, also covered stipends to parents and youth to be able to participate in the planning process.

OVP trains each regional coalition around topics like goal setting, coalition building, community organizing, the public health approach to violence prevention, and trauma-informed care. OVP also created a learning collaborative as a space for the regional coalitions to come together to share challenges, best practices, and learn from each other. In 2023, these local community coalitions, in alignment with OVP efforts, began focusing on gun violence prevention.

3. TPI Expansion

As described above, TPI was an existing violence reduction strategy at LADPH when OVP was launched, and is based on a three-part approach of prevention, intervention, and community capacity building. On July 13, 2021, the Board of Supervisors approved a motion to invest $5 million in the expansion of the program in the four existing TPI communities and to also expand it to five new communities, which were identified based on an analysis of crime data, homicide data, poverty rates, and recent increases in violence. This also allowed TPI staff to invest in enhanced evaluation and a peer workforce housed at OVP, including a team of Community Health Workers and a Community Violence Intervention Specialist.

OVP has continued to build infrastructure to support TPI work, including coordination with city public safety departments and hospitals in new communities, strategic alignments with diversion and youth development programs, and contracting with the Urban Peace Institute to develop recommendations regarding TPI’s expansion.

4. Implementing a Crisis Response Pilot Program

As part of its strategic priority to address trauma and the root causes of violence, OVP launched a Crisis Response Pilot Program to provide immediate peer support to individuals and families most directly affected by violence, as well as to support collective healing across the impacted community, including activities like vigils and healing circles, messaging about the unacceptability of violence, and linking survivors to long-term services to address mental health and well-being. The Care Action Response Team (CART), launched in July 2023, uses a hybrid peer approach and responds to a broad range of violent incidents. CART staff coordinate with complementary initiatives, such as Alternative Crisis Response, which diverts behavioral health and substance use calls from law enforcement to community providers.

The Crisis Response Program Pilot is currently funded at $440,000 per year and focuses on South Los Angeles communities with the highest rates of violence. OVP contracts with a community-based organization, Tessie Cleveland Community Services Corporation, to respond to incidents and conduct community outreach to support survivors, their families, and the surrounding community after a crisis incident has occurred. The program also engages peer specialists and the faith community as active partners in responding to community needs in the wake of violence.

In 2023, the County Board of Supervisors approved a motion establishing the Family Assistance Program within OVP, to provide burial assistance, system navigation, and grief counseling to families who have lost a loved one due to a death at the hands of a sheriff’s deputy or while in the custody of the sheriff’s department. OVP is working with county partners to implement these services and will be contracting with a community-based organization to provide healing support to communities impacted by deputy-involved shootings. OVP will also be working to develop policies and practices to reduce such incidents from occurring and to ensure a trauma-informed approach across country systems.

5. Advancing Trauma-Informed and Healing Systems Change

Through TPI, OVP staff are training fellow county agencies on the nature and impact of trauma and on the importance of working with a trauma-informed lens, particularly when providing services or otherwise interacting with families and youth. A growing body of research and evidence shows that trauma, when not addressed and healed, can have a major negative impact on behaviors and outcomes for individuals. Moreover, when government systems interact with individuals without an understanding of trauma, it is all too easy to trigger a trauma response and exacerbate existing trauma without knowing it.

To help address this, OVP staff conduct trainings for county agencies and for community-based organizations on trauma-informed and healing-centered care. In addition to these trainings and the host of available trauma-related educational resources and materials,52 OVP also engages in systems change work by helping organizations develop policies, engage in sustainability planning, and conduct assessments of their capacity to deliver fully trauma-informed services.

As of April 2024, OVP staff have conducted trauma-related trainings for a variety of county agencies, including the Department of Parks and Recreation and the County District Attorney’s Office. OVP’s Trauma Informed Care Specialist has also worked internally with the team to build their capacity to be trauma informed, and to address vicarious trauma. In 2024, this internal work expanded to staff and leadership throughout LADPH, with the help of a one-time state grant.

6. Changing the Narrative: Violence as a Public Health Issue

Finally, OVP staff are working on shifting the narrative around violence, both in terms of centering the lived experiences of survivors and also reframing violence as a public health issue—not just a law enforcement issue—requiring a comprehensive response. To help center survivors, OVP launched the Violence, Hope and Healing Storytelling Project, in partnership with the Department of Arts and Culture, which is an effort to document the experiences of residents who have experienced violence.53

OVP has also hired a communications strategist to develop a plan to educate policymakers, partner agencies, and the public at large about the importance of addressing violence as a public health issue, and to promote and provide transparency around the work of the office.41

Gun Violence Prevention Platform

In June 2022, OVP launched a 40-point Gun Violence Prevention Platform, with input from its County Leadership Committee (CLC) and Community Partnership Council (CPC). OVP is in the process of implementing four priorities identified by both the CLC and CPC:

- Support robust, commonsense gun safety legislation and promote gun safety education. OVP is currently implementing a gun safety initiative that includes the distribution of 60,000 gun safety locks, free of charge, through county hospitals and libraries and through a request form on its website. The gun safety initiative includes a billboard campaign sponsored by the Los Angeles County Medical Association and LA Care Health Plan to increase awareness of the importance of safely securing your gun—locked and unloaded.

- Improve school safety and increase access to comprehensive physical and mental health services. OVP is using $5 million in federal American Rescue Plan dollars to implement School Safety Transformation Grants, funding partnerships between community-based organizations and school districts to provide restorative programming and safe passages services.

- Promote social connection and healing through access to safe spaces and programs. In 2023, OVP hosted a series of five Youth Mental Health Summits across the county, reaching more than 500 youth participants. OVP is also funding nearly $20 million in American Rescue Plan dollars to invest in increased street outreach, HVIP, a Peer Learning Academy, crisis response, youth leadership and community healing programs, and a hardship fund in high-need communities across the county.

- Increase awareness of and access to gun violence restraining orders (GVROs) through a public awareness campaign. OVP has begun hiring staff to provide system navigation and training and is working with a consultant to conduct system mapping.

Summary

There is an important role for counties to play when it comes to addressing community violence, and Los Angeles County’s TPI initiative and its Office of Violence Prevention provide an example of what this can and should look like. Gathering data to identify priority communities within the county—particularly unincorporated areas that fall outside of any one city’s jurisdiction—centering survivor voices, allocating resources to implement intervention and prevention programs, helping to build capacity of impacted communities and of community-based organizations in the field, and coordinating a multi-sector response are all important features of this work.

Given its breadth and initial success, county leaders around the nation should seek to understand and replicate the core elements of LADPH’s Office of Violence Prevention.

JOIN THE FIGHT

Gun violence costs our nation 40,000 lives each year. We can’t sit back as politicians fail to act tragedy after tragedy. Giffords Law Center brings the fight to save lives to communities, statehouses, and courts across the country—will you stand with us?

For county leaders and advocates looking to expand their local response to community violence, there are several common elements from the three case studies above that should be carefully considered. While there is no one-size-fits-all approach that can be simply copied and pasted from place to place, these basic elements provide the foundation upon which an effective, customized response to community violence can be built.

1. Data Collection and Problem Analysis

In many localities in the US, gun-related homicide and shooting data is often incomplete, not up-to-date, and maintained in siloed agencies. Counties are uniquely positioned to leverage their own data collection resources and also help coordinate the data collection efforts of city agencies. In Allegheny County, for example, staff from the County Department of Human Services pulled together data from both healthcare records and local police records to create the region’s most in-depth analysis of homicide trends and patterns to date.

Data collection is also a function that county agencies—especially departments of public health—may be well positioned to take on, as Los Angeles County’s Office of Gun Violence Prevention has done. In Los Angeles County, the creation of a publicly available clearinghouse of gun violence data is one of the cornerstones of the county’s five-year strategic plan to address violence. Any such plan should include a review of local capacity to collect and analyze data pertaining to homicides and non-fatal shooting incidents. Among other benefits, this analysis can help to direct county investments and resources to the areas within the county where they will have the largest impact. This kind of data helped staff from the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health determine where they would implement the Trauma Prevention Initiative and related capacity-building efforts for local nonprofit organizations.

It’s not enough to conduct a one-time analysis of patterns and trends in a given moment in time. This information must be kept up to date through ongoing shooting reviews, where relevant stakeholders in law enforcement and in the community can discuss recent acts of violence, identify the community groups in the best position to respond, and take collective action to prevent the escalation of violence. This is exactly what the Allegheny County Department of Human Services has done by allocating a portion of its funding specifically to the implementation of shooting reviews.

An effective shooting review process requires cooperation from diverse stakeholders who may not trust one another, and counties can help overcome this by providing both financial incentives and by acting as a neutral bridge and convenor between these stakeholders, using county resources to create a platform for local collaboration.

2. Funding Evidence-Informed Strategies in Disproportionately Impacted Communities

A common link between Los Angeles, Allegheny, and Harris counties is the investment of resources to directly support evidence-informed services and programs designed to work with individuals at elevated risk for engaging in violence. Violence is not evenly distributed in any of these countries—rather, in all three counties, homicides and nonfatal shootings are clustered disproportionately in areas of concentrated disadvantage, structural racism, and inadequate public services.

In all of these areas, violence is both a cause and a symptom of inequity—and it will be very difficult to address other disparities until violence is brought down. As we have discussed in many other reports and publications, there are a number of evidence-informed strategies that have a proven track record for reducing violence in a relatively short period of time by concentrating culturally competent resources and services on the small number of individuals at high risk within a given neighborhood or community.54 This includes street outreach, hospital-based violence intervention programs, cognitive behavioral therapy, and trauma-informed mental health services.

In all three of the case studies explored above, county funds are being used to create competitive grant programs to implement or expand evidence-informed violence intervention models. This includes HVIPs in all three counties; Cure Violence, Becoming a Man, and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy in Allegheny County; a trauma-informed approach in Los Angeles County that also incorporates violence intervention and crime prevention through environmental design (the use of lighting and green spaces to address violence); and street outreach and violence interruption in Harris County.

There is no one single program that will end community violence, and counties should not force local communities to adopt a specific model—but counties can and should give some guidance and provide a menu of evidence-informed solutions for local communities to choose from, as Allegheny County did with its Community Violence Prevention Initiative. This will allow for increased local ownership over the solutions county leaders choose to pursue, which is an essential ingredient for any violence reduction strategy.

Instead of one-size-fits all, county leaders should be addressing community violence through the lens of an all-hands-on-deck approach that is built on universal best practices, but also tailored to local conditions.

3. Encouraging Coordination and Collaboration

For too long, addressing community violence has been viewed as the sole domain of law enforcement. This is akin to thinking that drug addiction can be solved strictly through punishment. As with the epidemic of drug use in the US, gun violence is a multi-faceted issue that requires a response from a host of different stakeholders—from the healthcare system to housing, education, and everything in between. One of the roles counties should play is to encourage different stakeholders to see how they fit within the violence prevention ecosystem and to incentivize collaboration and coordination between those stakeholders.

Allegheny County took this on directly by funding an organization to serve as a “Countywide Convenor” that was responsible for working with diverse stakeholders to build connections, share best practices, and engage in collective problem solving. The county is also incentivizing collaboration at the local level by funding “Community Quarterbacks” who are tasked with bringing together all the different stakeholders and role players needed to effectively carry out Local Violence Reduction Plans.

Similarly, Los Angeles County has funded the creation of regional violence prevention coalitions and earmarked funds to be used as stipends to encourage participation by young residents and other members of the community that may face barriers to participation. Through TPI, the county is also funding Community Action for Peace coalitions that bring together community members to identify drivers of violence and—critically—pursue solutions beyond just law enforcement. This led to a series of initiatives to reclaim public parks, which were identified as attracting violence crimes. It also led to partnerships with non-traditional allies such as the Parks and Recreation Department, and it helped to fill a gap in the unincorporated areas of the county that fall outside the responsibility of city government.

Every agency, organization, and individual has a role to play in ending community violence. County policies should be designed to encourage everyone to find their place and role in keeping the community safe—and not just with words, but with meaningful investment of county resources. Counties should also incentivize local stakeholders to come together to find common ground and implement shared solutions.

4. Capacity Building and Frontline Worker Wellness

There is increasing recognition that the field of community violence intervention has been underappreciated and dramatically under-resourced with respect to its importance in promoting public safety. Certain states and the federal government have taken steps in recent years to help build the capacity of the CVI field through funding technical assistance, professional development, and support for the health and well-being of frontline workers—who take on a job that is extremely challenging, rife with vicarious trauma, and sometimes outright dangerous.55

County governments should help continue to build capacity in the field and look for ways to fund not just the implementation of projects, but the measurement and improvement of capacity benchmarks, including the regional average pay for frontline workers, vitality of community-based organizations working to address community violence, and the ability of local groups to leverage both government and public funding streams.

At the federal level, for example, the Department of Justice’s Community Violence Intervention and Prevention Initiative (CVIPI) solicitation included a track specifically for intermediary organizations whose purpose is to work with smaller, grassroots organizations to build their organizational capacity.56 In Los Angeles County, the Office of Violence Prevention has earmarked funds specifically for the purpose of building the capacity of grassroots organizations that are doing violence intervention and prevention work. The county’s Trauma Prevention Initiative includes a capacity building component where consultants give operations and management training to grassroots organizations within the TPI priority communities.

Los Angeles is also at the forefront of prioritizing frontline worker wellness. The LA Peace Plan, created by a coalition of violence intervention organizations, calls for a $60,000 minimum starting salary for violence intervention workers. In addition, the region provides structured training and certification for the field through the Urban Peace Academy.57

At the state level, the California Violence Intervention and Prevention (CalVIP) grant program requires community-based and government applicants to include a plan and a budget for promoting and protecting frontline worker wellness. The state also earmarked funds specifically to work with grantee organizations to develop their practices around data collection and evaluation, in the form of workshops and on-demand support.58

In seeking to address community violence, county leaders should take responsibility for developing the capacity of frontline violence prevention organizations. This can include technical assistance, training, resources, and equitable pay for frontline staff, as well as leveraging intermediary organizations to help build the capacity of grassroot organizations.

GET THE FACTS

Gun violence is a complex problem, and while there’s no one-size-fits-all solution, we must act. Our reports bring you the latest cutting-edge research and analysis about strategies to end our country’s gun violence crisis at every level.

Learn More

Tackling gun violence—one of the most pressing public health crises of our time—requires an all-hands-on-deck approach. It’s time for county governments to take direct responsibility for their part of the solution. As the case studies of Los Angeles, Allegheny, and Harris counties illustrate, there are concrete ways to address the scourge of community violence. By encouraging the community violence intervention and prevention ecosystem to flourish, counties can play a pivotal role in bringing the gun violence epidemic to an end.

We’ve seen that it can be done, and now we need a courageous commitment to action. County leaders across the nation need to bring more stakeholders to the table—themselves included—and support collaboration, coordination, and the capacity of community-based organizations working on the frontlines.

The time to act is now.

This section includes resources to help county leaders and advocates to get started. If you’re ready to take steps forward in your county, please reach out to the GIFFORDS Center for Violence Intervention team for support.

Learn More

- GIFFORDS Report: Addressing Community Violence in St. Louis County

- Los Angeles County Office of Violence Prevention

- Allegheny County Community Violence Reduction Initiative

- Harris County Public Health, Community Health and Violence Prevention Services Division

- Mecklenburg County Community Violence Strategic Plan, FY2023 – FY2028

- National OVP Network

- Cities United, Reimagining Public Safety: Moving to Safe, Healthy, and Hopeful Communities

- Everytown’s City Dashboard: Gun Homicide

- GIFFORDS Report: Leveraging Intermediaries to Strengthen the Community Violence Intervention Field

- GIFFORDS Report: Investing in Intervention

Technical Assistance Providers

- National CVIPI Resource and Field Support Center

- The Health Alliance for Violence Intervention (The HAVI)

- Cities United

- National Institute for Criminal Justice Reform

- California Partnership for Safe Communities

- Community Based Public Safety Collective (CBPSC)

- Cure Violence Global

- Urban Peace Institute

- National Network for Safe Communities

- Advance Peace

- ROCA

Our Reports

Browse some of the resources Giffords Center for Violence Intervention has created and explore our progress at the local, state, and national level.

SPOTLIGHT

COMMUNITY INTERVENTION

Community violence intervention focuses on reducing the daily homicides and shootings that contribute to our country’s gun violence epidemic. We created Giffords Center for Violence Intervention to champion community-based efforts to save lives and improve public safety.

Read More- Deidre McPhillips, “As guns rise to leading cause of death among US children, research funding to help prevent and protect victims lags,” CNN, February 7, 2024, https://www.cnn.com/2024/02/07/health/gun-deaths-injury-research-funding/index.html.[↩]

- “California Violence Intervention and Prevention Grant Program – CalVIP,” California Board of State and Community Corrections, last accessed May 23, 2024, https://www.bscc.ca.gov/s_cpgpcalvipgrant.[↩]

- Molly Nagle, Liz Landers, and MaryAlice Parks, “Biden announces White House Office of Gun Violence Prevention,” ABC News, September 22, 2023, https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/biden-announce-white-house-office-gun-violence-prevention/story?id=103394253.[↩]

- Melissa Rose Cooper, “Historically low crime rates in Newark, new data,” December 28, 2023, https://www.njspotlightnews.org/video/historically-low-crime-rates-in-newark-new-data; City of Detroit Police Department, “Detroit ends 2023 with fewest homicides in 57 years, double-digit drops in shootings and carjackings thanks to DPD, federal, county, state, and community partnerships,” January 3, 2024, https://detroitmi.gov/news/detroit-ends-2023-fewest-homicides-57-years-double-digit-drops-shootings-and-carjackings-thanks-dpd; Amber Lee, “City of Richmond: Record low number of homicides in 2023,” January 16, 2024, https://www.ktvu.com/news/city-of-richmond-record-low-number-of-homicides-in-2023.[↩]

- Los Angeles County of Violence Prevention, “Early Implementation Strategic Plan, August 2020, http://www.publichealth.lacounty.gov/ovp/docs/OVP%20Countywide/OVP%20Strategic%20Plan%20August_2020.pdf.[↩]

- WTAE, Officials: Allegheny County homicide rate lowest since 2019, January 2, 2024 https://www.wtae.com/article/allegheny-county-homicide-rate-2023/46270630.[↩]