Addressing Community Violence in St. Louis County

Existing Strategies, Gaps, and Funding Opportunities to Support a Countywide Approach to Violence Intervention

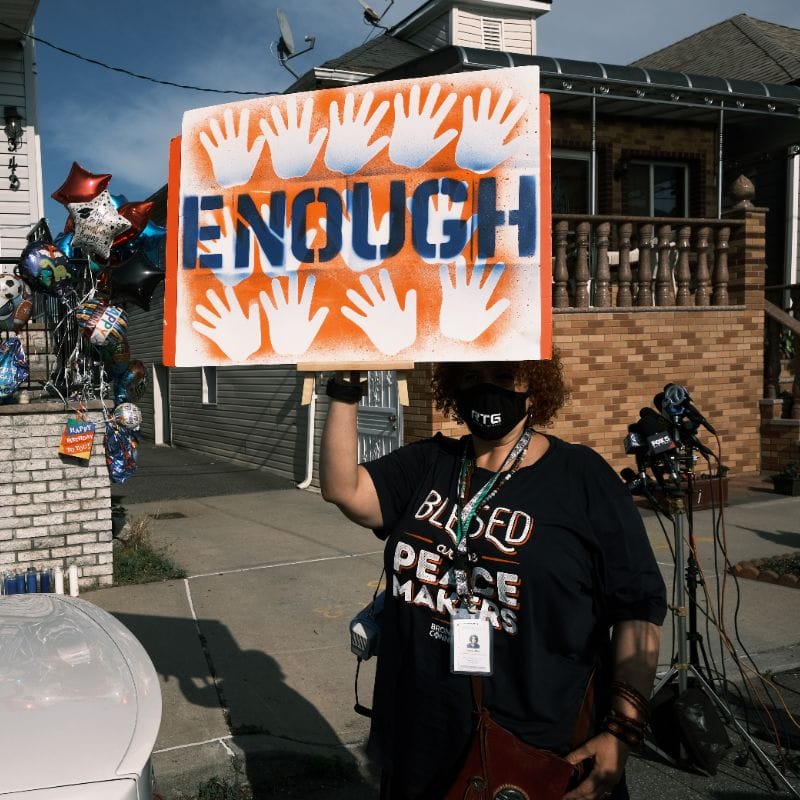

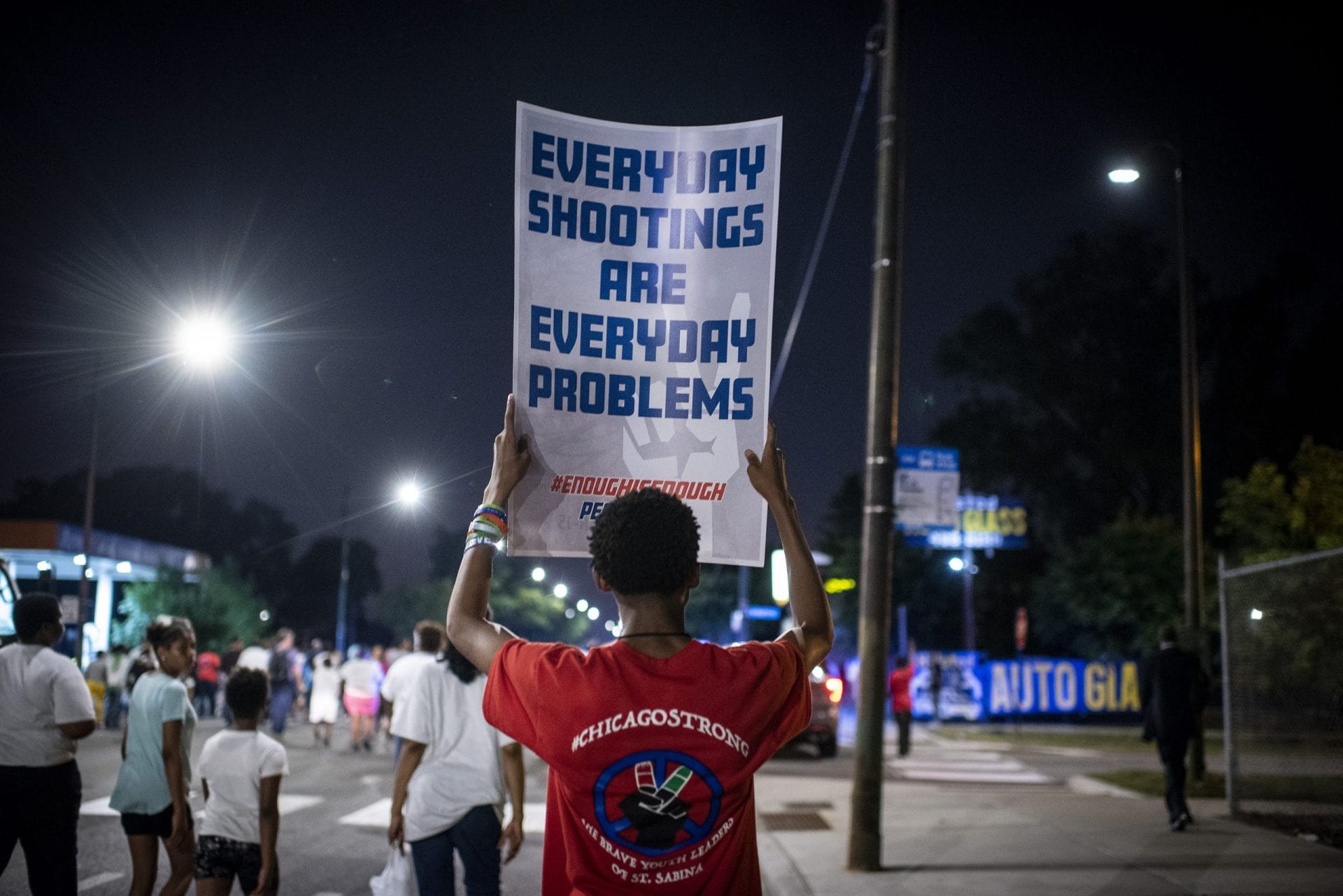

Community violence in the St. Louis region is a pressing public health crisis. While much of the attention falls on the City of St. Louis, where homicide rates are 16 times higher than the national average,1 the reality is that the County of St. Louis is facing a parallel epidemic of violence, with shootings that are crippling the lives of residents, especially residents of color —and particularly young Black men. This is an issue that is reducing the quality of life for residents and depressing economic growth for the entire region.

But there are steps that can be taken to turn the tide of violence in St. Louis.

Addressing Community Violence in the City of St. Louis

—Feb 17, 2022

In early 2022, Missouri Foundation for Health contracted with the Giffords Center for Violence Intervention to synthesize the information currently known about the scope and nature of the community violence epidemic in the County of St. Louis and identify strategies that need to either be implemented or scaled up to address this growing crisis. In recognition of the fact that this work requires a significant infusion of resources, Giffords staff and partners have also mapped out county, state, and federal funding opportunities to support the recommendations made here.

This report is a follow up to a similar project Giffords Center for Violence Intervention completed earlier in 2022, which looked specifically at community violence in the City of St. Louis—one of the few cities in the nation to see a significant reduction in homicides and shootings between 2020 and 2021. Taken together, these reports represent a roadmap of regional actions that can and should be taken to make the St. Louis region a safer, more equitable place to live.

At the time of our city-level report, St. Louis did not have a clear violence prevention infrastructure to support the variety of efforts taking place on the ground. In July 2022, Mayor Tishuara O. Jones signed Board Bill 65 that codified the establishment of an Office of Violence Prevention (OVP) within the Department of Public Safety. Additionally, the mayor committed nearly $13.6 million in American Rescue Plan dollars to funding community violence prevention and youth programs through 2026, although the OVP plans to explore funding opportunities to extend programs in a more sustainable manner beyond that timeline. “Bringing together law enforcement, social service providers, and community groups under this innovative new office, we can make strides to prevent violence crime in St. Louis,” said the inaugural director of the Office of Violence Prevention, Wilford Pinkey Jr.2

“Community violence” is defined by the United States Centers for Disease Control, is violence that occurs “between unrelated individuals, who may or may not know each other, generally outside the home. Examples include assaults or fights among groups and shootings in public places, such as schools and on the streets. Research indicates that youth and young adults (ages 10-34), particularly those in communities of color, are disproportionately impacted.”3 Community violence includes shootings, homicides, stabbings, physical assaults, and the unnecessary use of force by law enforcement.

This violence is the result of many complex systems and inequities, from segregation and disinvestment in communities of color to grave disparities in the criminal legal system, among others. But until the immediate bloodshed is dramatically reduced, progress on any larger social issue in St. Louis will be more difficult, as violence is both a symptom and a cause of inequity.

Community violence creates tremendous human suffering and also generates economic losses for the entire region. The National Institute of Criminal Justice Reform estimates that a single homicide in St. Louis costs taxpayers in the city, county, and state $1 million, and the public cost of a single nonfatal shooting is $534,000.4 Based on these estimates, homicide in the County of St. Louis in 2020 alone cost more than $192 million in healthcare, law enforcement, lost wages, and other related expenses.

To better understand the lived experiences of those committed to facilitating meaningful reductions of violence in St. Louis County, members of our team traveled to the county to have in-person conversations with community stakeholders representing government agencies, nonprofit organizations, and residents directly impacted by violence. This took the form of multiple stakeholder focus groups, which were generously hosted by North County, Inc., a regional development association,5 and one-on-one interviews with dozens of individuals in the St. Louis area about what they believe the gaps are as it relates to a county-level response to community violence. Giffords would like to deeply thank Rebecca Zoll and Evan Maxwell of North County, Inc., for their assistance in identifying stakeholders and setting up these meetings.

The team hosted virtual follow-up conversations and interviews with leaders from social service offices, county political leaders, community-based organizations, and law enforcement officials to get a firm grasp on the landscape of community violence and the evidence-informed efforts being supported. Additionally, a broad range of documents were reviewed to improve our comprehension of the type of data organizations collect and their overall impact on reducing community violence, including annual reports, intake assessments, geography-based service utilization heat maps, and relevant policy and budget documents. Over 100 different stakeholders were interviewed over the course of this project, and an invaluable amount of insight was shared. The Giffords team is tremendously grateful to the St. Louis community for their trust and candor during this process.

Community violence is a daunting challenge, but we know that progress is possible. This report is intended to assist St. Louis County leaders and community stakeholders in prioritizing—and funding—the most effective solutions for reducing community violence as quickly as possible.

MEDIA REQUESTS

Our experts can speak to the full spectrum of gun violence prevention issues. Have a question? Email us at media@giffords.org.

Contact

Before exploring the landscape of community violence in St. Louis County, it’s important to provide some context about the region and the county’s relationship with the neighboring City of St. Louis.

The County and City of St. Louis voted to separate in 1876 during what many refer to as the “Great Divorce.”6 This separation has withstood over a dozen attempts at reunification and continues to have a major impact on the entire region. To this day, the two entities remain entirely distinct, with separate county and municipal governments and public agencies. Over the years, the schism has presented challenges for both the city and county alike.

Fragmented Governments and Services

The St. Louis region is among the most institutionally fragmented metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) in the nation.7 It ranks third among all other MSAs in the US for the largest number of local governments and school districts per capita, according to a 2015 analysis by the East-West Gateway Council of Governments.8 Furthermore, research shows that this type of fragmentation, particularly as it pertains to school districts and municipal governments, is more likely to lead to racial and economic segregation.9 As of 2017, school districts in the St. Louis region are the sixth-most segregated of all major metro areas in the country.10

St. Louis County alone is made up of over 90 cities, towns, and census-designated places,11 the majority of which have their own municipal governments and are served by a patchwork of around 55 police departments.12 Not long ago, the number of police departments serving the county was closer to 80, but after numerous reports identified these disjointed police forces as a major source of confusion and distrust among residents,13 some jurisdictions worked to consolidate their resources to better serve the community. For example, the North County Police Cooperative, which was established in 2015, consolidated several police departments serving eight St. Louis County communities.14 While this marks significant progress, fragmentation remains an ongoing and serious challenge for the county.

Due to the incredibly fragmented nature of St. Louis County, comprehensive, municipal-level crime data for the county is not readily available. The Missouri State Highway Patrol (MSHP) aggregates and reports countywide homicide statistics, but still only captures a snapshot of violence in the county.

Though variations between law enforcement and CDC data are common due to differences in how data is collected and how homicides are classified, a comparison of MSHP and CDC data reveals that a large and significant number of homicides—sometimes as much as half of all homicides in a given year—are not captured by MSHP statistics.

Systemic Racism and the Delmar Divide

The Great Divorce also had a significant impact on the size of St. Louis City and County and their ability to grow. At the time the two entities diverged, the City of St. Louis was experiencing a period of rapid expansion and benefited from industry and a large, affluent tax base. The county, on the other hand, had a much more rural population, limited resources, and substantial debt.15

Today, fortunes in the city and county have reversed.

Borders drawn at the time of the separation nearly tripled the size of the city, but also restricted its growth. By 1950, the population of the City of St. Louis was at nearly one million residents and expected to rival major metropolitan areas like New York and Chicago.16 As of 2020, the city is home to about 300,000 residents.17

After 1950, the city experienced a period of rapid population decline. This occurred, in large part, as a result of “white flight,” a term that refers to the migration of white Americans from the cities to the suburbs that occurred in many American cities throughout much of the first half of the 20th century.18 While the number of people living in the suburbs grew quickly during this period, by 1970, just 4.5% of the country’s suburban population was Black.19 For the City of St. Louis, this exodus left behind an older, lower-income, and predominantly Black population, and whittled away at the city’s once robust taxbase.

Meanwhile, discriminatory policies like redlining worked to uphold and reinforce the segregation of Black residents by preventing them from owning or purchasing homes in some neighborhoods and labeling others as “hazardous” or “declining” due largely to the presence of Black homeowners.20

As a result of this discrimination, 98% of federally insured home mortgages nationwide between 1934 and 1962 went to white borrowers.21 This left most homeowners of color cash-strapped and unable to make the repairs necessary to maintain their homes, pass them on to future generations, and build generational wealth.

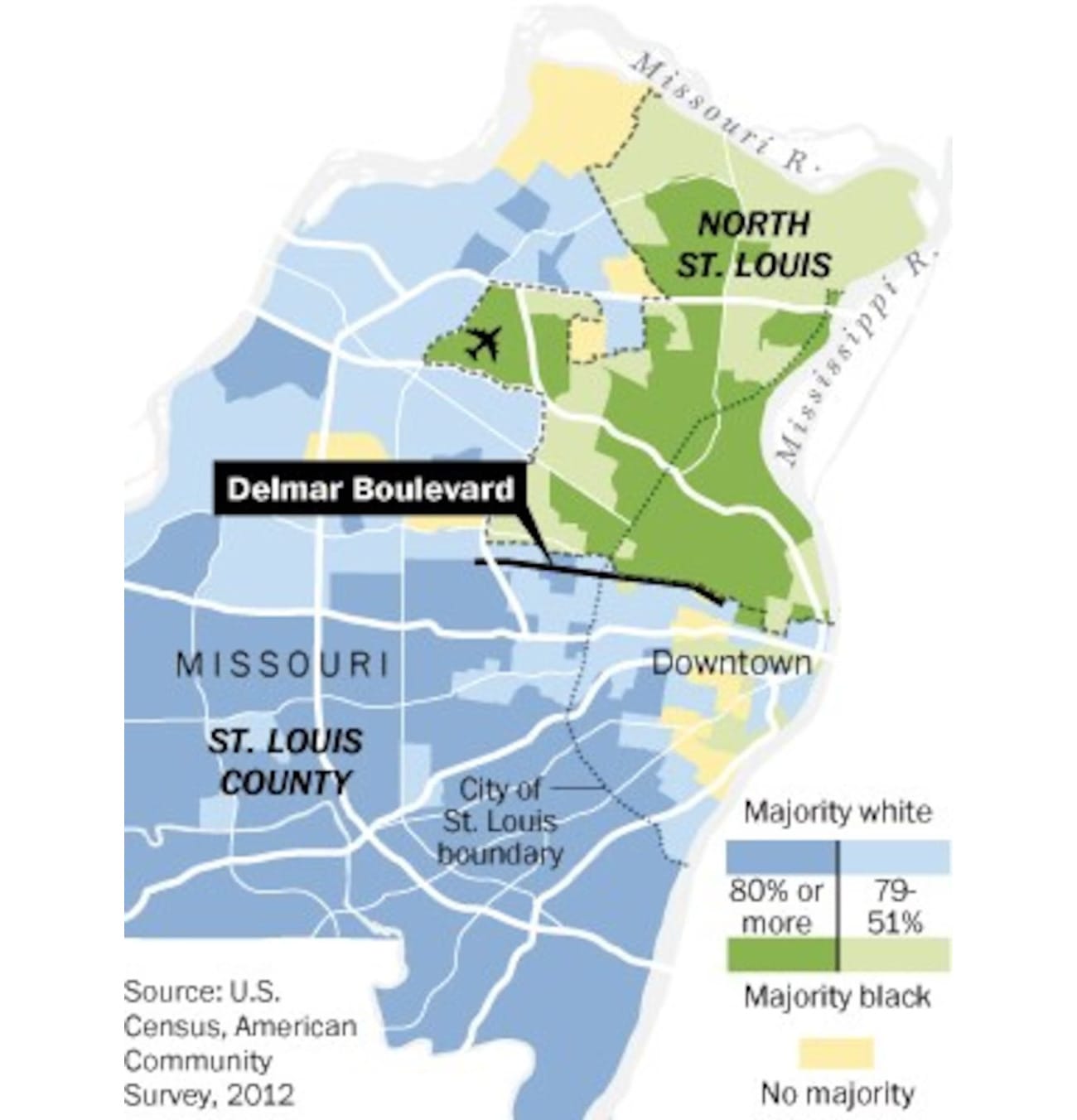

By the time the Fair Housing Act of 1965 passed, much of the damage was done, and deep structural divides were created. The Delmar Divide, as it’s often called, refers to an almost 10 mile-long road that spans across the City of St. Louis and part of the county, and divides the city into a northern and southern half, which have dramatically different demographics and huge disparities in wealth, income, and even life expectancy.22

During the Jim Crow era, the street separated white neighborhoods from Black neighborhoods, and today in the City of St. Louis, neighborhoods directly north of Delmar Boulevard are 98% Black with a median income of $18,000, while neighborhoods south of Delmar are 73% white, with a median income of $50,000.23 Out of the 50 largest metropolitan areas in the US, St. Louis is ranked as the seventh most segregated.24

Source: “A Picture is Worth 930 Words: The Delmar Divide,” Wiley Online Library, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/foge.12065.

In both the city and the county, vacant and dilapidated homes line the north side of the Delmar Divide, while homes worth hundreds of thousands cover the south side. It is a clear and troubling glimpse of how discriminatory policies continue to impact residents long after the laws have been changed.

From the City to the Suburbs

Still, from the 1970s on, a rapidly growing number of people of color began to settle in the suburbs, and by 1990, 37% of Black people residing in metropolitan areas in the US lived in the suburbs.19

As race and class are closely linked in this country, the number of low-income people moving to these more rural areas also increased significantly. Between 2000 and 2010, in the country’s largest metropolitan areas, the number of people living in poverty in American suburbs increased 53%. By 2010, 55% of people experiencing poverty and residing in a metropolitan area called the suburbs home.16 According to Professor Todd Swanstrom from the University of Missouri, St. Louis, the region was on the “leading edge” of these trends.

“Compared to other metropolitan areas,” writes Swanstrom, “more poor and minority households live outside the central city in the St. Louis metropolitan area. According to the 2010 census, only 30 percent of those in the metro area who identify as ‘black only’ live in the city of St. Louis.” Today, 27% of Black people living in the St. Louis metro area live in the City of St. Louis.

Many Black and low-income people moving to suburban areas of St. Louis encountered a very unfamiliar, complex, and in many ways less efficient system of governance in the county. As Swanstrom explains, “Instead of one city government and school district, they face a fragmented institutional landscape of smaller (and often weaker) municipalities and school districts.” Furthermore, many new residents moved to unincorporated areas that fall under the jurisdiction of a distant county government.25 The unincorporated areas of St. Louis County presently contain nearly one-third of the county’s total population and one-third of its geographic area.26

According to Swanstrom, the pattern of suburbanization of Black and low-income households in St. Louis follows Homer Hoyt’s sectoral model of neighborhood change, meaning that neighborhoods grow and expand as economic groups migrate outward along key transportation routes. As Black households in St. Louis have historically migrated north and west of the urban center,19 this theory helps explain how the divisions created by the Delmar Divide have extended from the city into the county. As Swanstrom explains, “Black suburbs are basically an extension of the segregated black communities in North St. Louis City.”16 As a result, people living in the northern part of the county experience many of the same hardships including a low per capita income, high poverty rate, and high rates of violence.

JOIN THE FIGHT

Gun violence costs our nation 40,000 lives each year. We can’t sit back as politicians fail to act tragedy after tragedy. Giffords Law Center brings the fight to save lives to communities, statehouses, and courts across the country—will you stand with us?

According to 2021 estimates from the US Census Bureau, St. Louis County—the largest county in Missouri—is home to nearly a million residents. Over two-thirds of people residing in the county are white (64.7%) and one-quarter (25.1%) are Black. The next largest racial or ethnic groups in the county are the Asian and Hispanic or Latino communities, who make up five percent and three percent of the population, respectively.27

The county is comprised of seven council districts and has 686,293 registered voters. St. Louis County is led by an elected county executive, Dr. Sam Page, and a seven-member county council elected from the seven council districts.28 While there are services that are provided county-wide, however, the 88 municipalities have primary responsibility for their own public safety, planning, street maintenance, and other local services. The unincorporated area of the county, which contains nearly one-third of the county’s population and one-third of its geographic area, comes under the jurisdiction of the county government.29

However, as St. Louis’s complex history demonstrates, these figures fail to accurately describe many parts of the county, in particular the experience of many Black residents. Approximately 83% of Black people living in St. Louis County reside in what is often referred to as “North County.”30 As described above, this area more closely resembles the highly segregated and underserved communities in the northern part of the city than it does the rest of the county.

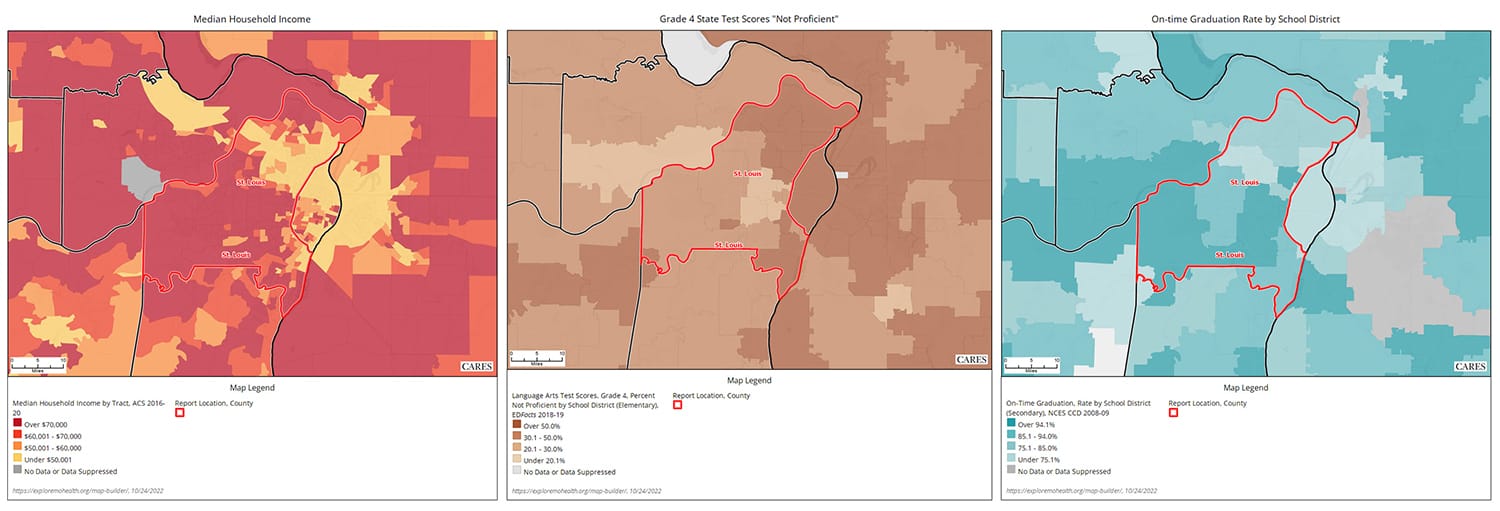

Source: Explore MO Health, https://cares.page.link/Bvvj.

Unlike the rest of St. Louis County, North County is majority Black. Nearly two-thirds of residents living in North County are Black while less than a third are white.31 The average per capita income in North County is about 40% lower than the rest of the county, and people are more likely to live in poverty, with 16.5% of the population living at or below the federal poverty level.32

Educational attainment in North County also lags behind the County as a whole. Almost three-quarters of North County fourth graders scored “Not proficient or worse” on state standardized tests measuring reading proficiency, compared to 55% of 4th graders countywide.33 North County residents are also more likely not to have a high school diploma (10%) than residents of the county more broadly (6%).16

Research shows that community level factors such as poverty, poor economic conditions, and a lack of access to quality education, among others, can lead to high rates of gun violence.34 As described above, North County struggles in many of these areas as a result of a history of discrimination and divestment from the North St. Louis region, where most of the county’s Black population resides. This is in line with research from Northeastern University, which suggests that many community-level factors are the result of deep structural inequities rooted in racism.35

Community Violence in St. Louis County

Though conversations concerning violence in the St. Louis region tend to focus on the city, the county also struggles with a serious violence problem and high rates of shootings and homicides.36 Between 2016 and 2020, St. Louis County averaged nearly 160 homicides per year, almost 90% of which were committed with a firearm. During the same period, the county saw an average homicide rate of 17.5 per 100,000 residents.37

Though this is significantly lower than the homicide rate in the neighboring City of St. Louis (48.5 per 100,000), the county experiences 34% more homicides per capita than the rest of Missouri (11.5 per 100,000) and more than 2.5 times the national homicide rate (6.4 per 100,000).16

The number of homicides in St. Louis County has increased by more than 78% between 2016 and 2020, and in 2020, the most recent year for which the CDC provides data, the county suffered 192 homicides, 94% of which were committed with a gun.16 However, according to the Missouri State Highway Patrol, which as explained above does not capture the full picture of violence in the county, the number of homicides committed in St. Louis decreased by 15% in 2021.38

While many stakeholders in the St. Louis region are focused on preventing youth violence, very few people under the age of 18 are the victims of homicide in the county or the city. According to our analysis of CDC data, the average age of a gun homicide victim in the county is about 31.5 years old, nearly identical to the average age of a gun homicide victim in the city.39 In the county, 61% of homicide victims are between the age of 18 and 35, while only seven percent of homicide victims are 17 or younger.39

Homicides in the county take a disproportionate toll on the Black community, who make up roughly a quarter of the population but account for almost 90% of gun homicide victims countywide.

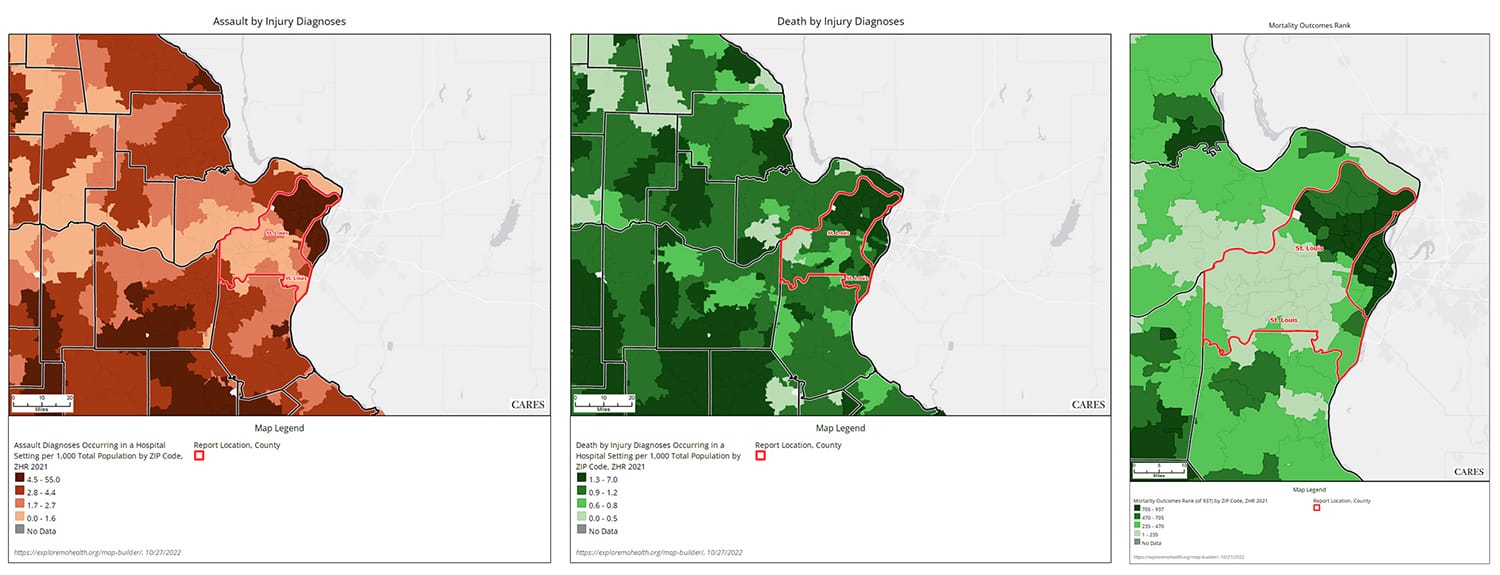

This violence overwhelmingly takes place in North County, where the vast majority of Black residents reside, and systemic barriers have created pockets of concentrated disadvantage. Murder and homicide data compiled by the St. Louis County Police Department (SLCPD), media reports aggregated by the Gun Violence Archive, and hospital utilization data all reveal that a disproportionate share of violence occurs in North County.

According to SLCPD, 67% of homicides within the department’s jurisdiction—which includes just under 50% of the county—occur in the North County and Jennings Precincts.40 Media reports aggregated by the Gun Violence Archive reveal that 72% of homicides occur in North County municipalities.41 Hospital inpatient, emergency department, and outpatient injury-related data from Washington University further shows a concentration of assaults, injury deaths, and high mortality rates in North County, as evidenced by the heat maps below.42

Source: Explore MO Health, https://cares.page.link/Bvvj.

For this reason, this report focuses on efforts and solutions in the North County area, but it’s important to understand that violence impacts every single resident of St. Louis County. Even for residents of relatively safe neighborhoods, the economic impact of community violence is staggering.

Given this, reductions of homicides and shootings in North County will not only save lives, but also bring economic and health benefits to the entire region and is an investment that is unquestionably worth making. From employment to tourism, there are a multitude of reasons to take a regional approach to reducing violence and adjusting the mindset that harm only touches a fraction of the St. Louis community—everyone is affected.

Risk Factors for Community Violence

In addition to these general trends, research has also established several individual and community-level risk factors that, when present, make it more likely that a person will commit or be the victim of community violence. The presence of risk factors helps indicate where interventions and services need to be focused, while protective factors indicate what kinds of interventions and services are most likely to make a difference.

Individual Risk Factors

As the St. Louis Youth Violence Prevention Partnership’s 2018–2023 Strategic Plan describes, individual risk factors for young people include:

- Impulsiveness

- Youth substance use

- Antisocial or aggressive beliefs and attitudes

- Low levels of school achievement

- Weak connection to school

- Experiencing child abuse and neglect

- Exposure to violence in the home or community

- Involvement with delinquent peers or gangs

- Lack of appropriate supervision

- Parental substance abuse

- Parental or caregiver use of harsh or inconsistent discipline

“Depression, anxiety, chronic stress and trauma, and peer conflict and rejection are also associated with youth violence perpetration and victimization. Youth who are arrested, particularly before age 13, have a heightened risk for future violence and crime, school dropout, and substance abuse.”43

The relationship between prior acts of violence and exposure to violence are particularly strong. One study found that exposure to gun violence—being shot, being shot at, or witnessing a shooting—doubled the probability that a young person would commit a violent act within two years.44 Research shows that in areas where rates of violence are high, an individual who is admitted to the hospital with a violent injury has an up to 40% chance of being reinjured again within five years.45 Moreover, if an individual is exposed to social networks that engage in community violence, it increases the likelihood that he or she may become either a victim or a perpetrator of community violence.46

This is why interrupting cycles of violence by tailoring resources and interventions to those at high risk is so important: stopping one violent act now can prevent dozens of future acts of violence.

Community Risk Factors

Community-level risk factors for violence in the St. Louis region include:47

- Residential instability

- Crowded housing

- Density of alcohol-related businesses

- Poor economic growth or stability

- Unemployment

- Concentrated poverty

- Neighborhood violence and crime

- Lack of positive relationships among residents

Several of these key risk factors, which increase the probability that a person will suffer and/or inflict harm, are explored in more detail below.

Protective Factors for Community Violence

Protective factors may reduce the occurrence of violence or make the outcome less impactful. At a general level, addressing any of the risk factors listed above, at both the individual and community level, will help to reduce violence, including “household financial security, safe and stable housing, economic opportunities, increasing access to services and social support, residents’ willingness to assist each other, and collective views that violence is not acceptable.”16 A St. Louis-specific analysis by the Youth Violence Prevention Partnership identified the following protective factors:16

- Healthy social, problem-solving, and emotional regulation skills

- School readiness and academic achievement

- Positive and warm parent-youth relationships

- Positive peer and adult mentoring relationships

- Supportive social networks

- Access to mental and behavioral health services

- Steady employment

A US Department of Justice diagnostic project from 2017 showed how violence can be addressed even while certain risk factors remain present. Researchers compared four St. Louis neighborhoods, all with high levels of poverty, but only two with high rates of violence, and found key protective factors included fewer vacant houses, good public lighting, and less presence of trash. This is in line with other findings that “physical environments of schools, parks, and business and residential areas that are regularly repaired and maintained and designed to increase visibility, control access, and promote positive interactions and appropriate use of public spaces are also buffers to violence.”48

Access to social services that can address the risk factors of violence and provide additional protective factors is critical as well. One study found that “having services that are within a two-mile radius of a person can serve as a protective factor to reduce recidivism,”49 which is why increasing access to services for those at high risk of engaging in violence is a crucial aspect of any locality’s violence reduction strategy. A 2017 focus group of adults living in high-violence areas in St. Louis echoed this finding as well, reporting that in order to reduce violence, “additional resources and services are needed to meet the needs of residents.”50

This report examines violence reduction strategies in the County of St. Louis through the lens of the risk and protective factors discussed above, and recommends the expansion and implementation of specific initiatives based on those factors. This is in line with the consensus finding that “reducing violence requires multi-prong approaches that target the community, businesses, schools, criminal justice, social services, and the individual,” with successful initiatives marked by their consideration of the factors that most influence violent behavior.51

With that context established, the next section of this report examines the current responses to community violence that the Giffords team was able to identify in our research and interviews. No community is starting from scratch in the fight against violence, and it’s important to identify and understand the area’s existing assets.

GET THE FACTS

Gun violence is a complex problem, and while there’s no one-size-fits-all solution, we must act. Our reports bring you the latest cutting-edge research and analysis about strategies to end our country’s gun violence crisis at every level.

Learn More

At the city level, St. Louis is already implementing a number of evidence-based strategies to address community violence, yet most of these strategies are at the scale of pilot programs rather than robust, institutionalized solutions. At the county level, there remains much to be desired in terms of a meaningful fiscal and strategic commitment to community violence intervention efforts. Many of the existing strategies, as detailed below, serve a significant number of county residents yet receive little to no direct support from the county itself. Moreover, there is a need to bolster efforts centered around designing a strategic plan for violence reduction across the county that appropriately leverages some of the programs that are already in operation.

The existing programs and efforts fall into five major categories: coordination, data collection and analysis, services for survivors of violence, services to address the root causes of violence, and law enforcement. At this point, most of these are being implemented as individual programs, on a relatively small scale, and in siloes.

Coordination

It is now widely recognized that because community violence is a multi-dimensional issue with a number of root causes from poverty to trauma, it can only be effectively addressed with a coordinated response from a range of public and private stakeholders.52 In the greater St. Louis area, one of the only entities dedicated to coordinating and improving a regional response to community violence is the St. Louis Area Violence Prevention Commission, making it an important resource for addressing violence in St. Louis County.53

St. Louis Area Violence Prevention Commission

The St. Louis Area Violence Prevention Commission (VPC) originated as a partnership between stakeholders at Washington University in St. Louis and United Way of Greater St. Louis, which saw the need for better coordination among the many individuals and groups working on the epidemic of violence in the region. It was later bolstered by the Saint Louis Mental Health Board, which dedicated executive-level staff time to move the group from planning to implementation.54

Today, the VPC is a regional, cross-sector initiative working to reduce violence and promote collaboration between community residents, community-based organizations, and local government agencies.55 With the understanding that residents of color have uniquely tense relationships with law enforcement entities that impact perceptions of legitimacy, the VPC has made an explicit effort to address the systemic issues that undermine these relationships.

In 2019, the commission issued a survey to police and community stakeholders to understand how police legitimacy could be improved through a racial equity lens. These efforts culminated in a “Statement on Policing & Violence Prevention in St. Louis County,”16 which lays out several concrete policy reforms the organization supports, as well as the county entities responsible for the implementation of each. Although all of the recommendations are of critical importance, there are three in particular that would have direct, immediate impact on the efficacy of community violence intervention in the county, all of which are echoed in this report:

Not every situation calls for a police response, nor is a police response always the most appropriate response to a crisis. For example, mental health emergencies and nonviolent neighborhood disputes could be resolved with non-police entities equally committed to ensuring public safety that specialize in these specific issue areas. The VPC has recommended a shift towards leveraging the training of these social service providers through a civilian public safety response network for 911 callers who need assistance unrelated to crime.

While the pain and trauma associated with a homicide is undeniable, there is also a very real need to pay better attention to those who suffer from the consequences of nonfatal shootings. VPC data shows that for every homicide, there are 20 aggravated assaults—a number that applies to both the city and the county. Given this gap, the VPC has worked to convene a group of social service providers and victim advocates to support a nonfatal shooting response system. However, a gap that has yet to be met relates to property repairs: a less obvious, but incredibly disruptive consequence to community violence (e.g. boarding up windows, replacing locks, fixing doors). Initiatives such as these merit greater investment as survivors work to find peace and safety after violence.

The ramifications of community violence are not solely felt by a select number of loved ones, but rather an entire community that becomes destabilized by trauma and distress in the aftermath of violence. Seeing as the majority of nonfatal shootings and homicides happen in public spaces, it is important to build a sense of cohesion within communities that encourage them to find solutions that work. To the VPC, this means building the capacity of residents to lead violence prevention efforts in areas of the region that are most impacted in a sustainable way through trainings, mobilization, and community building.

The VPC now has more than 150 organizational members representing education, health care, law enforcement, local government, neighborhood groups, and social services in both the City and County of St. Louis. There are a number of working committees that allow individuals to contribute to the collective effort, including in the areas of community engagement, policy and systems change, service delivery, evaluation, and communications. The VPC as a whole meets quarterly, and subcommittees meet monthly to provide regular opportunities for networking and information sharing. The group’s priority areas for 2022, which apply equally to both the City and County of St. Louis, are to advance an agenda around:56

- Police legitimacy

- Trauma-informed care and safe spaces for young people

- Responses to nonfatal shootings

- Supporting evidence-based program implementation

- Community engagement and leadership development

- Engaging municipal governments in VPC’s action plan

Although it is a regional entity, at this point in its development the VPC has more participants and contacts from the city than the county. This is at least in part due to the fact that unlike the city, which has increasingly embraced VPC as a thought partner in strategic planning and gathering input from community members and other stakeholders,57 St. Louis County has not yet fully leveraged the potential of partnership with VPC and its network of committed residents, organizations, and advocates to help coordinate county-specific violence reduction efforts. This is a strategic miss for the county.

Reflecting the city’s greater engagement with VPC, the group has a “Municipal Engagement Taskforce,” and VPC leadership sees a strong need for a similar committee to also oversee engagement efforts with the county, particularly if the county is to carry out any of the recommendations contained in this report. Doing so in coordination and with the support of the VPC will be an important way to gather community input, create external accountability, and disperse news and opportunities to a broad array of stakeholders.

Services for Survivors of Violence

Exposure to violence is one of the strongest risk factors for future violence: in certain areas, the violent reinjury rate is as high as 40%.45 This means that providing effective support services and interventions to survivors of violence is a powerful violence reduction strategy, reducing individuals’ risk of being victimized again and of seeking retaliation. There are a number of programs offering these kinds of services to survivors of community violence, and the St. Louis region has one of the only networks of hospital-based violence intervention programs in the country. However, these efforts remain underfunded, and as will be discussed below, despite the fact that at least half of their service population are county residents, they currently receive no financial support from the county itself. This needs to change, since support services for survivors of community violence (and for the families of homicide victims) are such a fundamental part of an effective regional violence reduction ecosystem.

Life Outside of Violence

Life Outside of Violence (LOV), formally referred to as the St. Louis Area Hospital-Based Violence Intervention Program (STL-HVIP), is an evidence-based strategy to improve outcomes for victims of violence and prevent future violence, based on the insight that exposure to violence is one of the strongest risk factors for future violence16 As the LOV concept paper explains, “Provision of quality screening, intervention, discharge planning, and follow up for this population is necessary to reduce the likelihood of subsequent violent injury and death. Hospitals are the primary location where patients who have suffered a violent injury seek medical care and thus are uniquely positioned to interrupt the cycle of violence for these high-risk individuals.”58

Source

Purtle, J., et al. (2015). Cost-benefit analysis simulation of a hospital-based violence intervention program. American journal of preventive medicine, 48(2), 162–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2014.08.030

To interrupt this cycle, HVIPs deploy culturally competent case managers to meet with violently injured patients in the hospital. Those that meet the criteria and voluntarily choose to join the program receive up to a year of intensive case management and other forms of assistance, depending on their individual needs and circumstances. Multiple studies, including several randomized clinical trials, have shown that HVIPs reduce reinjury rates for participants and improve other outcomes—saving lives and creating significant cost savings for health care systems.

In St. Louis, LOV was launched in 2018 by the Institute for Public Health at Washington University and is a partnership with four different hospitals (St. Louis Children’s Hospital, Barnes-Jewish Hospital, SSM Health St. Louis University Hospital, and SSM Health Cardinal Glennon Children’s Hospital) and three research universities (Washington University, Saint Louis University, and University of Missouri-St. Louis). LOV represents one of the first regional HVIP networks in the nation.

St. Louis City and St. Louis County residents ages eight to 30 who are injured by gunshot, stabbing, or blunt trauma, and who have been seen at a participating hospital, are eligible to enroll in the LOV program. For the purposes of this report, it’s important to note that approximately 50% of LOV’s clients are county residents.

Each site employs licensed clinical case managers and outreach workers to build relationships with victims of violence and connect them with services and provide immediate counseling. Each case manager has a maximum caseload of 20 participants. Following medical treatment, a trained case manager works with each participant and his or her family for up to one year to develop and maintain a plan to stay safe, connect to community resources, and to receive treatment, support, and guidance.59

Keyria Jeffries is a case manager with LOV and is based at St. Louis Children’s Hospital, where she screens young people admitted with violent injuries and flags eligible cases for initial contact and follow-up with her community outreach worker partner. If a patient agrees to participate in the program, Keyria provides ongoing therapeutic case management. For her young client population, this often means working with school systems, the child’s family or caregiver, church, or whatever other systems and activities constitute the young person’s support system. Keyria helps identify her clients’ needs and then work within their support system to help address those needs. One recent client, an 11-year-old, was admitted to the hospital after becoming the victim of seriously violent bullying. The dispute that led to the violence continued over social media, and Keyria is currently working with both the girl’s mother and the school system to create a safety plan.

Many of the families Keyria is serving are dealing with multiple stressors based around the inability to meet basic needs, especially food and housing. “A lot of the violence with young people is really just being in the wrong place at the wrong time,” Keyria reported.16 “People can’t work on higher level things—whether it’s school or trying to figure out a career, or anything else, really—when their basic needs aren’t being met. 99% of our job is working on those basic needs and stabilizing people.”

A success with one client illustrates how LOV’s work prevents future violence by looking at root causes and helping to put people on a different path. Keyria once had a nine-year-old client who was admitted to the hospital after being attacked at school by an adult security guard. “This was a kid from a really supportive family, but they saw him struggling with his grades, starting to lose interest in school. And when you’re in third grade, you still have a whole lot of school left.” Keyria was able to identify that this child was disengaged because he felt unsafe at school because of this incident. “Once we figured that out and were able to get him into a different school, he just thrived,” Keyria said.16 “He’s become an honor roll student. It’s not that he didn’t like school, but when you don’t feel safe that can come out in a lot of harmful ways unless it gets addressed.”

As of January 2022, LOV had enrolled more than 196 survivors of violence, and LOV graduates have had a collective reinjury rate of seven percent, with no instances of homicides or acts of retaliation known to LOV staff.60 That’s a three times lower reinjury rate compared to 21% among a matched control group from the four LOV hospitals that did not participate in the program.61 While this is important progress, additional resources are needed—both to ensure that LOV is able to reach as many victims as possible, and to ensure that fewer and fewer people are needing those services in the first place.

LOV partners with a number of hospitals in St. Louis City including: Barnes-Jewish Hospital, SSM Health St. Louis University Hospital, St. Louis Children’s Hospital, and SSM Health Cardinal Glennon Children’s Hospital. All LOV-affiliated hospitals are situated in St. Louis City, however over 50% of clients come from the county. Despite the large utilization of LOV services by county residents, LOV receives no direct support from the county. Instead, funding for the program comes mainly from an HVIP grant through the Department of Justice and a fiscal commitment from the hospitals themselves. Additional funding would allow for more staff to increase coverage and also for the expansion of a physical space for receiving and working with clients.

Victim of Violence Program – St. Louis Children’s Hospital

In any given year, the emergency department at St. Louis Children’s Hospital treats an average of 250 young people for violence-related injuries, with approximately 55–60% coming from the county.62 In 2020 alone, over 100 children seen by St. Louis Children’s Hospital were shot with a firearm—more than any full year in the hospital’s history.63 The Victim of Violence Program (VOV) was established to prevent the recurrence of violence and to interrupt the development of trauma, particularly in the lives of children between the ages of eight and 19 years old who have been shot, stabbed or assaulted, or involved in domestic violence.64

VOV begins outreach within the hospital setting. A social worker connects with the child and his or her family members and lets them know about the basics of the program and that a VOV mentor will make contact in the next 24 hours. VOV mentors then meet with the child and their family to build a relationship and assess needs. If the family agrees to participate, the VOV mentor will work with them to “develop goals and treatment plans and to process the reasons that led up to the treatment in the emergency department.”16 Mentors can and will communicate with a range of individuals within a child’s life, including school personnel, deputy juvenile officers, court personnel, police officers, and community agency staff. They are uniquely accessible to participating children through hospital-furnished cell phones and are available 24/7 via phone for emergencies.

Once a VOV mentor has conducted a needs assessment for the participating child, the two work collaboratively to identify the appropriate time frame of services and meeting intervals. Although there are no requirements for meeting frequency, participants are required to meet with their mentor for at least six sessions to maintain enrollment. A participant is discharged from the program after mutual agreement with their VOV mentor but is always welcome to reinitiate contact should they feel the need to do so. In cases where there is sporadic participation in the program, the mentor will ultimately close the case after multiple prolonged periods of no contact after one final attempt to reach out to the child’s family to see if they are still interested in participating.

“We have a 96% success rate with our kids,” says Warren Hayden, a retired youth program manager for St. Louis County’s Department of Human Services who is now a consultant for VOV.65 “One of the main challenges right now is that we need to improve our acceptance rate. We need more resources to be out in the community proactively so that people know what this program is and are more likely to take advantage of the services we offer.” The program’s partners include law enforcement agencies, families courts, and school districts in both the city and county. VOV receives funding from donors to St. Louis Children’s Hospital, but does not receive direct financial support from the County of St. Louis.

The BRIC and The T

HVIPs help provide services to victims of community violence who are treated in a hospital setting, but a large number of gunshot victims are also discharged without extensive treatment and simply given instructions on how to provide for their own self-care. Dr. LJ Punch, a trauma surgeon, noticed that many gunshot patients were simply not receiving a high quality of care, which was extremely harmful not just to the health of the individual, but to overall public safety. This need was also brought to his attention by Kateri Kramer-Chapman, the director of LOV, who was hearing that clients were not having their needs met in terms of pain management and that this was preventing the physical and mental healing needed to break cycles of violence.66

“We were seeing that today’s poorly treated bullet injuries were like the gunpowder driving tomorrow’s shootings,” he said in an interview.16 Patients, mostly young Black men, struggling with untreated chronic pain and trauma were not getting the healing they needed from the health care system—a staggering 30% of patients seen after the BRIC was first opened needed to have bullets removed from their bodies.

That’s worth repeating, because the implications are profound. Gunshot victims in the St. Louis region, mostly young Black men, are literally being discharged from emergency rooms with bullets still in their bodies. This population, says Dr. Punch, largely suffers in silence. “Despite the severe nature of gunshot wounds, they get an average of 4.2 hours of care and then they are left alone to care for themselves,” he said. ”If this were another public health issue, like TB, that’s simply not what we do.”16

To address this glaring gap, in November 2020, Dr. Punch founded the Bullet Related Injury Clinic (BRIC) to provide responsive, trauma-informed, accessible, and culturally competent care to individuals who have been discharged in the aftermath of a violent injury.67 Annually in St. Louis, more than 2,000 people experience bullet injuries, and about 50% are discharged from the emergency department without ever being admitted, leaving many survivors to care for their wounds without support—especially the 55% who are uninsured.68

“This is creating a gap in services provided by HVIPs like LOV. The BRIC has to be a part of the way that HVIP services get introduced in the ambulatory setting,” says Dr. LJ Punch.69 Without a referral to LOV from the BRIC, there is no way that this large population of gunshot survivors would even know about the services and supports available to them.

As described by the Wellbeing Blueprint, a national plan for reforming major public systems to achieve racial equity, “Too often, traditional service delivery models create false divides between community-strengthening activities and the services provided. The BRIC is radically different. Whereas hospitals deliver technical care primarily focused on physical healing, the BRIC combines medical care with a community-based approach to create long-term resiliency for patients, their families and the community.”68

Potential patients can self-refer themselves to the BRIC or may be referred by one of the four major trauma centers in the region. The BRIC also created a physical box that is distributed at the trauma centers that provides patients what they need for wound care and pain relief, which introduces people to the BRIC and its free services. “They can’t just go to CVS for wound care, it’s expensive and confusing,” said Dr. Punch. “The wound care box is imperative because it’s a gesture that helps build trust. The BRIC is giving you something, and this is who we are.” For individuals that provide their contact information, staff from the BRIC generally follow up within 1–3 days.

The BRIC received more than 600 visits in its first year of operation (the original goal was 200, but demand was three times that) and accomplished high participant retention rates with over 77% of patients returning for additional care after their first visit (compared to a rate of closer to 20% in traditional settings),66 and 80% of returning patients completing as many as six visits.16 Preliminary findings show that less than 20% of participants associated with the BRIC reported subsequent unplanned emergency department encounters—less than the regional average.70

The gunshot survivors treated for free at the BRIC have a number of needs, from pain management to therapy to bullet removal. One young patient who was shot back in 2014 recently had a bullet removed from him by clinicians at the BRIC—eight years after his original injury. To address the physical aspects of bullet wound care, the BRIC offers physical therapy, occupational therapy, chiropractic care, and pain management services. For mental health and trauma-related needs, the BRIC offers a therapist who conducts group meetings, a chaplain for spiritual care, and referrals to a wide array of partner organizations, including LOV, Alive & Well Communities, and the Crime Victim Center.16 Clients of the BRIC can also access a host of services offered by its umbrella organization and physical headquarters: The T.

The T

The disproportionate impact of violence on communities of color raises concerns regarding structural racism, particularly as it pertains to health equity and access to quality care. To address this gap, The T was created to serve the St. Louis region as a health education and resource center, assisting those returning to their community after discharge as they prepare to heal physically and emotionally from their injuries.71 “The T promotes holistic healing from trauma related to bullet injuries and overdose in St. Louis,” the organization’s mission statement declares. “We transform healthcare delivery through education and anti-racist, community-based medicine.”16

The T, a nonprofit organization, was born out of an initiative to expand certifications for Stop the Bleed training,72 a national campaign developed in 2012 to assist individuals in recognizing life-threatening bleeding and swift intervention, and to put community health into community hands. Led by Dr. Punch and the philosophy to provide “profound access,” The T now exists to ensure resources are accessible to those who are recovering from the impact of trauma, including bullet wounds, opiates, COVID-19, and homelessness.

At its physical location on Delmar Boulevard in the City of St. Louis, The T provides free clinical services, Stop the Bleed training, harm reduction services including overdose prevention training, mental and behavioral health services, and a host of referral options through partner organizations. “It’s important that The T is based in community and people getting served by survivors and those with lived experience,” noted Dr. Punch.66

Unfortunately, neither The T nor the BRIC have received funding from St. Louis County, despite the fact that 50% of their clients are county residents. They predominantly receive funding through a combination of city, state, federal, and philanthropic support.

Crime Victim Center

The Crime Victim Center (CVC) is a resource for victims of violent crime, witnesses to violence, and families of homicide victims in the St. Louis area, with approximately 60% of its clients being residents of St. Louis County.73 The CVC provides trauma-informed counseling and therapeutic services, support groups, advocacy services, resource mapping, legal assistance, and help with victim compensation to cover the cost of medical bills and other expenses related to violent victimization.74 As described in more detail below in the “Law Enforcement” section, CVC and St. Louis County Police Department (SLCPD) partnered in 2022 to have a full-time CVC-employed homicide advocate to serve the families of homicide victims within SLCPD’s jurisdiction.

The CVC is a nonprofit agency that provides services to over 7,000 victims of crime in St. Louis annually. Services provided by the CVC are free of charge and applicable to a range of crimes including burglary, robbery, identity theft, assault, homicide, hate crimes, domestic violence, intimate partner violence, sexual assault, among others.73 For victims of shootings, CVC receives referrals for services from partner organizations like the BRIC, LOV, and SLCPD.

CVC partners with over 30 agencies across the St. Louis region in an effort to provide an expansive range of social service referrals to those in need. In 2020, 683 clients received assistance in filing Order of Protection in the context of domestic violence situations, 576 clients were supported in obtaining victims’ compensation, and over 2,100 cumulative hours of therapy was provided to participants.75 The organization manages this with a staff of approximately 20 people and an annual budget of around $1 million—but it currently lacks the capacity to meet the huge demand for its services.

With the exception of a grant subcontract from St. Louis County’s Domestic Violence Court to support CVC’s Order of Protection advocate position for individuals facing domestic violence, the county provides no financial support for any other aspects of CVC’s work as of September 2022, despite the fact that a majority of CVC clients are county residents.

In sum, while there are a number of excellent organizations serving victims of violent crime in St. Louis County both in the hospital and the community setting, there is a lack of adequate resources for this important work. This is a strategic miss for the county when it comes to reducing community violence and should be a priority area of improvement, as we discuss in the recommendations section below.

Services to Address the Root Causes of Violence

In addition to prior violent victimization, there are a number of other primary root causes of violence that need to be directly addressed in order to improve public safety in St. Louis County. This includes risk factors such as repeated exposure to the criminal legal system; barriers to educational and employment opportunities; lack of awareness of trauma and resources to heal from trauma; substance abuse; and deficiencies in the neighborhood infrastructure, including the presence of vacant lots and building, the absence of light and safe communal spaces like parks, and the presence of food deserts.

Alive & Well Communities

Part of Alive & Well Communities’s mission is to activate communities to heal. It works with communities by naming racism and systemic oppression as trauma that impacts the well-being of all; responding to the impact of historical trauma to foster healing for current and future generations; elevating community wisdom by centering those who are most impacted; and leading innovative solutions based on the science of trauma, toxic stress, and resiliency. This approach helps those impacted understand trauma, which can be a strategy to disrupt community violence.

Gun Violence in Hispanic & Latino Communities

—Mar 05, 2025

Alive & Well Communities is the product of two separate trauma-informed initiatives, Trauma Matters KC and Alive & Well STL, which came together in 2017 to help a wider range of residents address the trauma they have experienced at the hands of cultures and systems.76 It serves communities across the State of Missouri, and partners with school districts and health systems across the region to offer tailored evidence-informed workshops, workplace assessments, and trainings.

Since its inception, Alive & Well Communities has trained over 27,000 individuals and its work has been associated with reductions in school suspensions, increased student attendance rates, and lower rates of burnout among staff.77 As it directly relates to community violence, Alive & Well Communities has partnered with organizations like the BRIC to provide trauma training customized to the needs of the trauma experienced by gunshot victims.78

“Gun violence and trauma go hand in hand, and it often starts with kids in Missouri witnessing violence at a very early age,” said Christin Simpson, Alive & Well’s director of Healthcare Activation.16 “People can be walking around with trauma that can cause them to go from zero to 100 in an instant, and not even know it. If we teach people about their emotional triggers, maybe they will pull triggers less often.”

Given the important connection between community violence and trauma, there is a need for St. Louis County to expand access to the kinds of trauma-informed training, workshops, and other resources that Alive & Well Communities is providing. Hospital systems in the St. Louis region are particularly in need of this training, Simpson said. “If places where gun violence victims were going were more trauma-responsive by applying their knowledge surrounding the science of emotional trauma, you wouldn’t need the BRIC to bridge that gap. In many cases, people need help to process the trauma from how they were treated in our hospitals following such a serious injury.”16

Pathways to Progress

Pathways to Progress is an initiative created by Catholic Charities of St. Louis and St. Francis Community Services that seeks to empower community members through long-term case management.79 “Our goal is to help whole families, not just one person,” says Maryn Olson, program director for Pathways to Progress, “We work with families for two to four years, helping them navigate the system to figure out how life could be different and better.”80 Pathways has a staff of nine, which includes seven case managers—known as “Member Advisors”—who provide clients (“Members”) with intensive and long-term case management services. All of Pathways’s Member Advisors are seasoned professionals who are trained in trauma-informed care.

This is important because nearly all of Pathways’s Members and their families have experienced various forms of trauma, and according to Olson, every Pathways family has likely suffered some form of violence—often gun violence. “Many members have been the victims of domestic violence, lost family members to gun violence, experienced shootings, had their cars shot at, so violence is a regular challenge for our members,” Olson said in an interview.16 “We’ve had a member whose son was shot and killed while sleeping at home in his bed, and another whose kids were playing with a gun and the gun accidentally went off—killing one of the children.” Without the kinds of support services offered by a program like Pathways, these episodes of traumatic violence can often be the start of a hard-to-break cycle of further violence.

The program started as a pilot in 2016 serving eight zip codes in North St. Louis County with the highest levels of intergenerational poverty in the county, eventually expanded to cover the entire North County area in 2019, and also grew into North St. Louis City in 2020. Most referrals come from word of mouth. Potential Members are eligible for participating in Pathways if they live in a service area, have a family income at or below 130% of poverty level, have a minimum level of housing security, and demonstrate that they want to join the program and participate regularly.16

The Pathways intake process is extensive, and staff will look at a potential member’s life goals and needs, from safety to food access to mental and behavioral health. The intake process is used to develop a customized service plan that is reviewed with the member every 90 days to track progress and adjust as needed. For mental health needs that are beyond what Member Advisors can provide, Pathways has access to mental health professionals through partnerships with organizations like St. Louis Counseling.

With an annual budget of approximately $1 million, Pathways to Progress is engaged with 74 families, including 200 children in the St. Louis region as of September 2022, and is funded almost completely through grants and private donations. While Pathways’s core focus is economic mobility and empowerment for its Members, the organization also measures outcomes related to quality of life, school engagement, school performance, successful referrals, and housing.

Olson sees violence in the St. Louis region as being fueled by a feeling of hopelessness. “When you have no hope or sense of the future, it doesn’t matter what happens to you—you could go to jail and that doesn’t matter to you,” she said. “There’s really an epidemic of hopelessness, which makes people feel helpless and they lash out to try to find some sense of power.”80 Pathways is working to create hope and possibility in situations where none seems to exist.

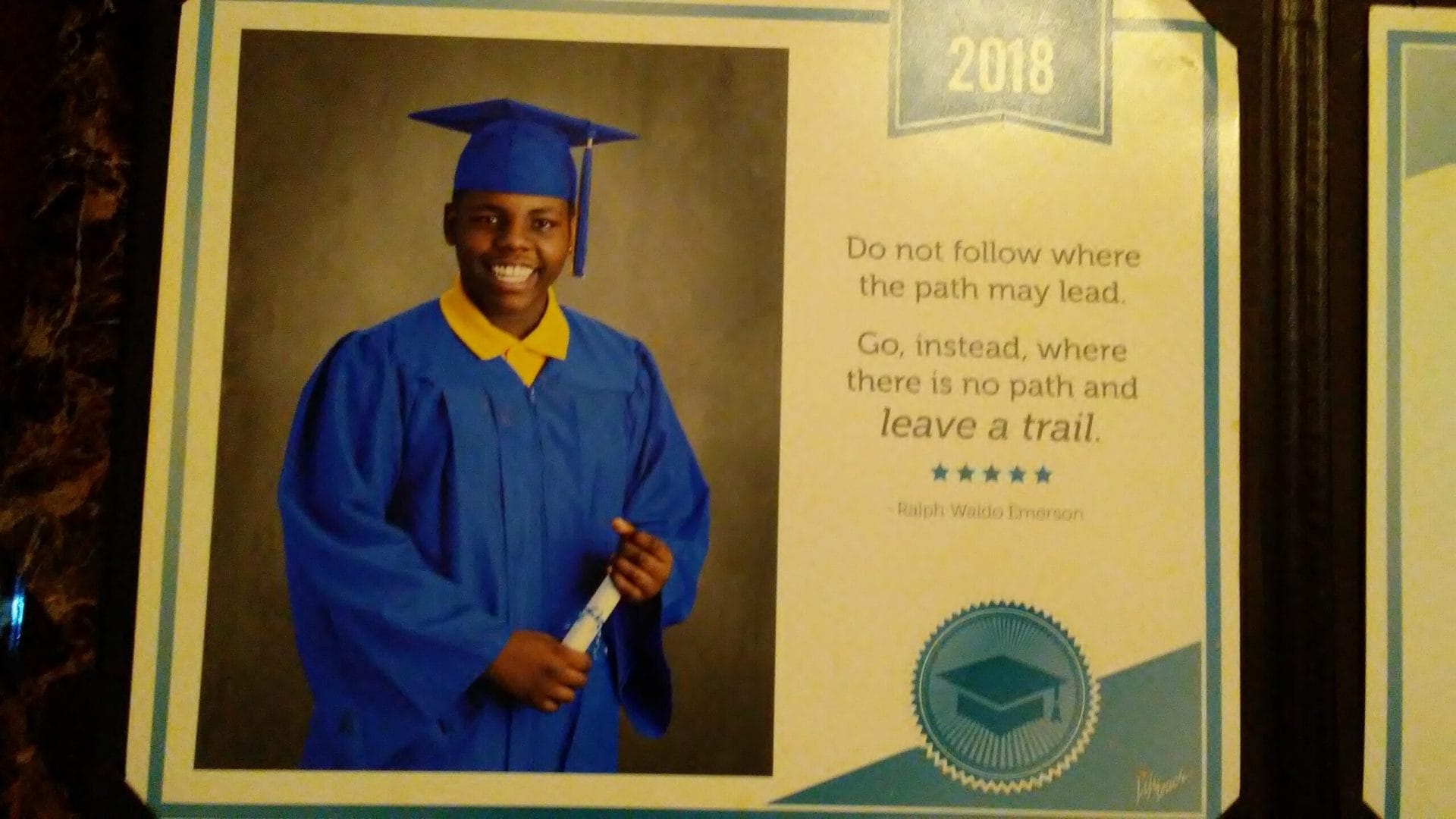

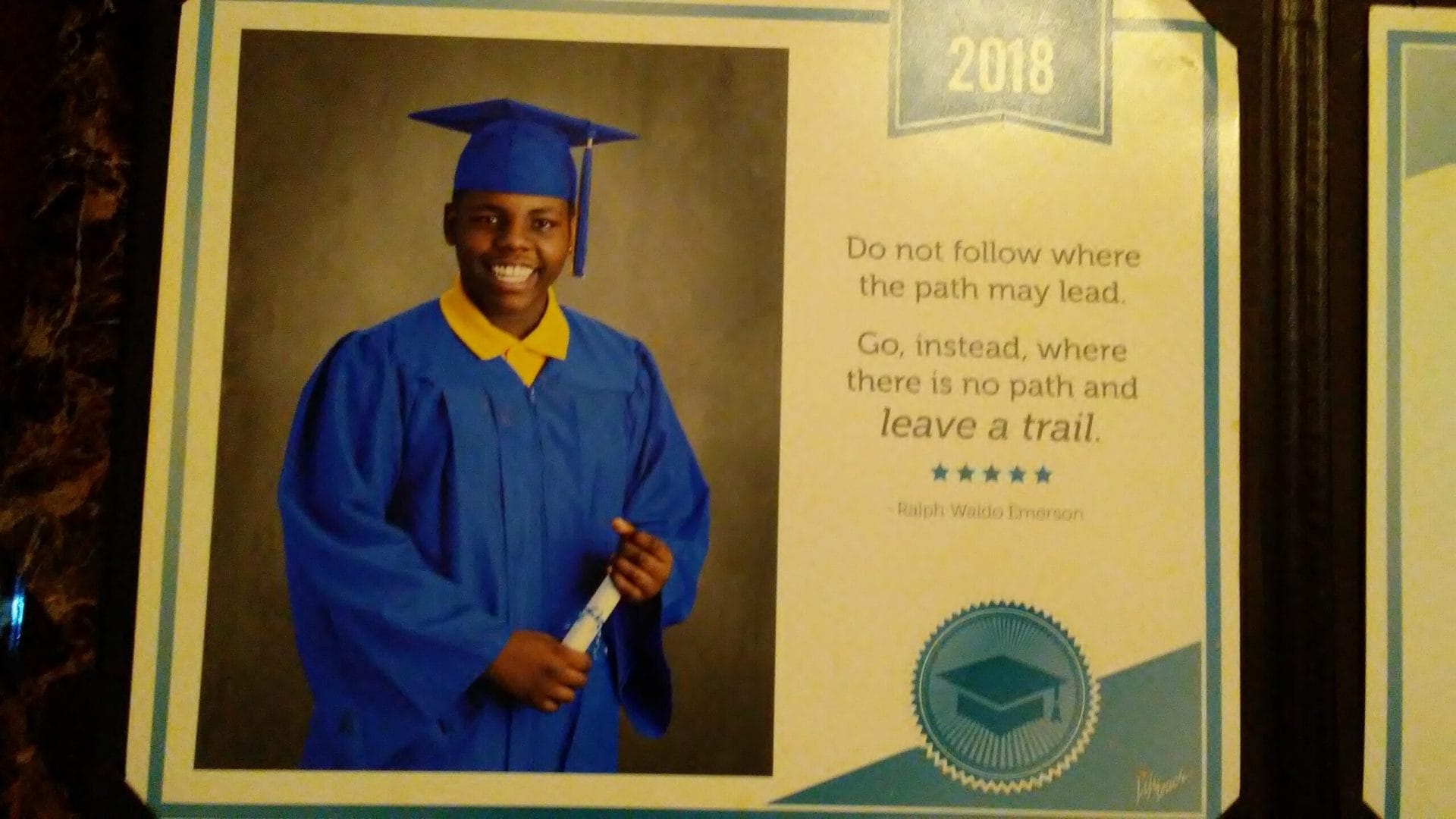

One member’s story illustrates just how tragically common violence can be within the population Pathways serves. Before joining Pathways, Ebony Davis lost her son’s father to gun violence in a case of mistaken identity. This happened right in front of the car where Ebony was sitting with her two children, who were just two and eight months old when this senseless killing occurred. Thirteen years later, after joining the Pathways program to help her turn her life around, the unimaginable happened: shots rang out in the middle of the night, and a number of bullets came screaming through her Glasgow Village home. Ebony, terrified, ran to check on her 15-year-old son, Antione, who was asleep in bed. When she couldn’t wake him up, she realized what had happened: Antione had been struck in the head with a stray bullet and was already gone.

Antione was a warm, outgoing person who loved going to school. “He was a clown—was always making people laugh,” Ebony recalled. “He was going to school every day. He would have graduated from high school this year if he had lived.”16 The shooting happened at 5 a.m. and it took two hours for law enforcement to arrive on the scene. No arrest was ever made and the case was never solved. During this period of crisis, it was Ebony’s Pathways Member Advisor, Sarah, who was there for her. Pathways arranged for Antione’s funeral costs to be covered by their partner, the St. Louis Society of St. Vincent de Paul, connected Ebony with counseling, and advocated to the Housing Authority to help keep a roof over Ebony’s head during this traumatic time in her life.

Three years after the killing of her son, Ebony is still on her feet, though it’s still incredibly hard to keep going. “I still have trouble sleeping, but I’m working everyday,” Ebony said during an interview, wearing a t-shirt with a photo of Antione. But there are also the things that keep her going: her daughter, Ronetta, graduated high school last year, and Ebony is helping raise her new grandchild. Where there were no other sources of support after Antione’s killing, Pathways was there in a way that made all the difference. “I didn’t get help from the county or the city during this. There might have been a detective that showed up at Antione’s funeral, but that was it. Pathways though, they were there for me. They helped me get through all this.”

Ebony’s experience with gun violence in St. Louis County, tragic as it is, is not an isolated case. The teenage son of a friend of hers, another Pathways member, was also shot and killed on July 4, 2020. Olson also recounted the experience of another member with teenage children, whose home was shot up multiple times. Instead of assistance or support, she was told to stop reporting the incidents or her residence would be written up as a “nuisance property,” and there was pressure placed on her landlord to have her evicted.

These cases illustrate the gap in services and supports that exist for victims of violence in St. Louis County. “In too many cases, law enforcement and government agencies are acting as if the victim is at fault, rather than what they are: a victim,” said Olson.16 “When police show up to these scenes of violent crime, they need to immediately assign a social worker or a case manager, so that people can learn about the available resources.”

The current response, she said, is totally inadequate. “This is somebody’s child, and until you fix this, it sends the message that Black lives don’t matter.”

Re-Entry Community Linkages

Every year over 700,000 individuals are released from America’s jails and prisons.81 Many returning citizens are released to their families and communities yet face the challenge of learning how to reintegrate into society and connect with quality comprehensive services to support their fresh start. Prior acts of violence and repeated exposure to the criminal legal system are both risk factors for future violence. Yet, too often, formerly incarcerated individuals return to society without adequate support systems to reduce their risk. This helps explain the more than 40% crime recidivism rate in Missouri, and this is why reentry services are an integral component of an effective violence reduction ecosystem.82

Re-Entry Community Linkages (RE-LINK) is a program within the Integrated Health Network (IHN), a health care intermediary that convenes care entities and bridges the gap between the public health system and community support system for young adults returning home from regional jails. RE-LINK leverages community health workers (CHWs) and over 20 partners in the Health and Social Services Network (HSSN) to provide essential wraparound support to clients that mitigate health inequities and reduce the likelihood of recidivism.83

RE-LINK services initially launched in the City of St. Louis in 2016 with the help of a grant from the federal Office of Minority Health. That grant, however, expired in 2021, and RE-LINK became funded through a contract with the St. Louis County Department of Public Health. The program now operates exclusively at the county level and largely supports individuals between the ages of 18 to 45 years returning from St. Louis County jail, nearly all of whom have been impacted by community violence as either a victim, a perpetrator or—as is often the case—both.84

CHWs identify potential clients pre-release and begin to provide services upon enrollment. These services include “release readiness classes” that cover topics like trauma, goal-setting, employment readiness, substance abuse, and an overview of community resources.85 CHWs also provide trauma-informed emotional support and help clients navigate a legal system that is archaic and difficult to understand. Prior to release, CHWs host classes and workshops with incarcerated clients to identify clients’ needs and identity supports that will be needed for a successful reentry into society, including identifying community-based partners that provide services in the areas of mental health, job training, substance abuse prevention, and housing.

While RE-LINK has not been serving St. Louis County long enough to have impact data available, its record from several years of operation in the City of St. Louis suggests a significant positive effect on participants, with 97% of clients not returning to jail, more than 63% improving employment outcomes, and close to half of clients enrolling in insurance and reporting improved health outcomes.16

STL Reentry Collective

In 2020, STL Reentry Collective, an organization started by formerly incarcerated individuals, sought to assess the types of services available within the City and County of St. Louis that support returning citizens.86 The group realized that while there are limited reentry services available, the most pressing need for returning citizens is financial support. Through community donations, the organization was able to raise funds and provide mutual aid financial assistance to those trying to reestablish themselves within the community. The organization also created a comprehensive reentry resource guide and is currently working on the creation of a documentary that will highlight the stories, needs, and experiences of those who are formerly incarcerated.87

STL Reentry Collective plans to provide trauma focused workshops that will accompany the viewing of their documentary series. According to Harvey Galler, co-founder of the STL Reentry Collective, “the workshops will aim to provide information on how unaddressed trauma impacts incarcerated individuals, including contributing to higher rates of recidivism. Participants will be connected to mental health organizations that specialize in trauma treatment within the area.”88 Through a unique partnership with the St. Louis County libraries, these workshops will be held at various county locations and will be open to the public.

STL Reentry Collective views the trauma-focused workshops as an essential component of violence prevention initiatives within the city and county. Harvey argues that while “meeting basic needs are critical upon release from incarceration, it is also necessary to identify and treat unresolved trauma because it often perpetuates the revolving door of recidivism.”16 Formerly incarcerated individuals who have higher rates of recidivism are further locked out of resources and are less likely to receive adequate services due to institutional record and the stigma attached to repeat offenders.

“Providers and the public in general often do not want to deal with those who have higher rates of recidivism. However, it is those individuals who are more likely to have the higher rates of unaddressed trauma and are at greater risk for perpetrating violent crime,” said Harvey.16

Department of Public Health Initiatives

Within the St. Louis County Department of Health there have been two federally funded, multi-year projects to address trauma, inequity, and community violence in the north part of St. Louis County: ReCAST and Project RESTORE.However, it should be noted that the funding for both programs expires in 2022 and the need for sustainable violence reduction efforts remains. In addition to these programs, the county Department of Health also participates in a collective effort to analyze data and identify community health priorities, known as Think Health St. Louis.

ReCAST

The Resiliency in Communities After Stress and Trauma (“ReCAST”) program was created as a response to the 2014 murder of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, to leverage the voices of regional leaders in shaping how systems work to promote well-bring, resiliency, and community healing in the St. Louis Promise Zone.89 The Promise Zone encompasses parts of both St. Louis City and St. Louis County, including: Bellerive Acres, Bel-Nor, Bel-Ridge, Berkeley, Beverly Hills, Cool Valley, Country Club Hills, Dellwood, Ferguson, Flordell Hills, Glen Echo Park, Greendale, Hazelwood, Hillsdale, Jennings, Kinloch, Moline Acres, Normandy, Northwoods, Pagedale, Pine Lawn, Riverview, University City, Uplands Park, Velda City, Velda Village Hills, and Wellston.90 Areas within the St. Louis Promise Zone are those that need more resources related to economic mobility, violence prevention and intervention, education, and overall community health.

In 2016, the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) awarded $4.7 million to the St. Louis County Department of Health, the City of St. Louis Department of Health, and the St. Louis Mental Health Board to launch ReCAST, which supported community projects in the form of micro-grants in five key issue areas:

- Violence prevention

- Youth engagement

- Peer support

- Mental health

- Trauma-informed care

ReCAST has supported a few projects that have either directly or tangentially bolstered violence reduction initiatives happening in the region. For example, Community Health in Partnerships (CHIPs) was funded through ReCAST to expand its apprenticeship program where high-school aged youth that reside in the Promise Zone were trained to become peer health educators. Through this effort, nearly 1,200 youth were taught how to de-escalate and resolve conflict, as well as healthy coping skills.91 Another project, called the Metro Theater Company (MTC), similarly focused on conflict resolution through art. MTC connected educators and over 2,200 students to artists who would perform interactive shows on nonviolent resolution of conflict to model prosocial de-escalation skills for youth.92

As a method to mitigate inequality, each project underwent a participatory budgeting process, meaning that community members of the St. Louis Promise Zone themselves were directly involved in deciding which projects would receive grant funding. Nearly 1,000 residents across St. Louis County and City took part in the process, and approximately $2 million in grant funding was allocated to community projects—equating to 31 organizations being funded and 5,006 youth receiving services through ReCAST-funded projects.93 ReCAST funding expired in July 2022, but the county Department of Public Health has brought key ReCAST leaders onto its staff to continue the work as part of a broader plan to address violence within St. Louis County.

The overall impact of ReCAST on county residents has been generally positive with many feeling like the projects undertaken were accurate interpretations of community need. Over 900 residents participated in community voting to determine the top proposals within each funding cycle. However, some community members indicated that they would have liked to see a few more priority areas included in the micro-grant solicitations, namely those centered on disability services and sexual health education. Residents also lifted up the need to include more youth voices and expand service delivery to areas outside the Promise Zone.

Researchers at St. Louis University also found that 52% of community members felt an improved sense of resiliency as a product of ReCAST contracted projects. Moreover, the participatory budget process was positively received, with some residents expressing feelings of empowerment by having their voices incorporated into the decision-making process for projects happening in their community.16

Project RESTORE

Project RESTORE (Reconciliation and Empowerment to Support Tolerance and Race Equity) was a first-of-its-kind project in the St. Louis region, which started as a four-year collaborative in 2017 to address youth violence, to help schools become trauma-informed, and to provide teachers with professional development training on the impact of trauma on their students.94 The project leverages restorative justice research and community partnerships, and adapts community policing to implement targeted programming in order to meet three main goals: “(1) reduce problem behaviors (including violent conduct, bullying, and school dropout), (2) promote resiliency, school performance, and healthy decision-making, and (3) improve cultural competency among school personnel and police.”95

The federal Department of Health and Human Services’s Office of Minority Health awarded $1.7 million to the St. Louis County Department of Public Health, which was then distributed to project participants, including the St. Louis County Police Department; three school districts in north St. Louis County: Normandy, Hazelwood, and University City;96 the Police Athletic League (PAL); and researchers at the University of Missouri – St. Louis (UMSL) and Southern Illinois University – Carbondale (SIU), to fund implementation and evaluation of the program.

Project RESTORE staff enrolled a cohort of students from 7th to 10th grades at each of the three target school districts, which were chosen based on epidemiological analysis showing that the majority of violence in St. Louis County was taking place in the north part of the county.97 Services for this cohort included training for students to become “Teenage Health Consultants,” who then engaged in peer-to-peer education on issues like violence, mental health, and substance use, as well as tutoring, after-school and summer programs through PAL—including several out-of-town, multi-day field trips, and training for school personnel.95 One PAL officer even adopted a student who was facing housing insecurity and numerous personal challenges.